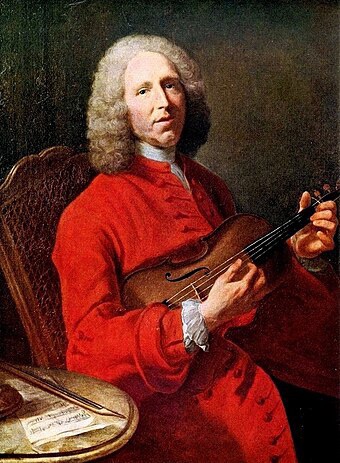

‘Leslie Howard presented an all-Russian programme this July. Famous for his scholarship and understanding of Liszt, Howard’s love of the Russian composers Glazunov, Borodin and Rubinstein is unsurprising in that they all owe a debt to the Hungarian composer and pianist in one way or another. It was Liszt who took the burgeoning Borodin under his wing and conducted his music whenever he could, and Borodin dedicated his orchestral masterpiece In the Steppes of Central Asia to Liszt; Glazunov visited Liszt in Weimar in 1884 (Liszt arranged for the teenager’s First Symphony to be performed, and the Second Symphony was dedicated to Liszt in gratitude); and although Liszt did not need to help the young Rubinstein in promoting his compositions, the lad had spent much time studying the master’s performance technique and was soon to be celebrated as the greatest pianist after Liszt.’

Aleksandr Porfiryevich Borodin (1833-1887) Petite Suite and Scherzo (1885)

Au couvent • Intermezzo • Mazurka in C •

Mazurka in D flat • Rêverie • Sérénade •

Scherzo – Nocturne – Scherzo

Aleksandr Glazunov (1865-1936) Thème et Variations Op. 72 (1900)

Interval

Anton Rubinstein (1829-1894) Piano Sonata No. 4 in A minor Op. 100 (c.1876-80)

I. Moderato con moto • II. Allegro vivace •

III. Andante • IV. Allegro assai

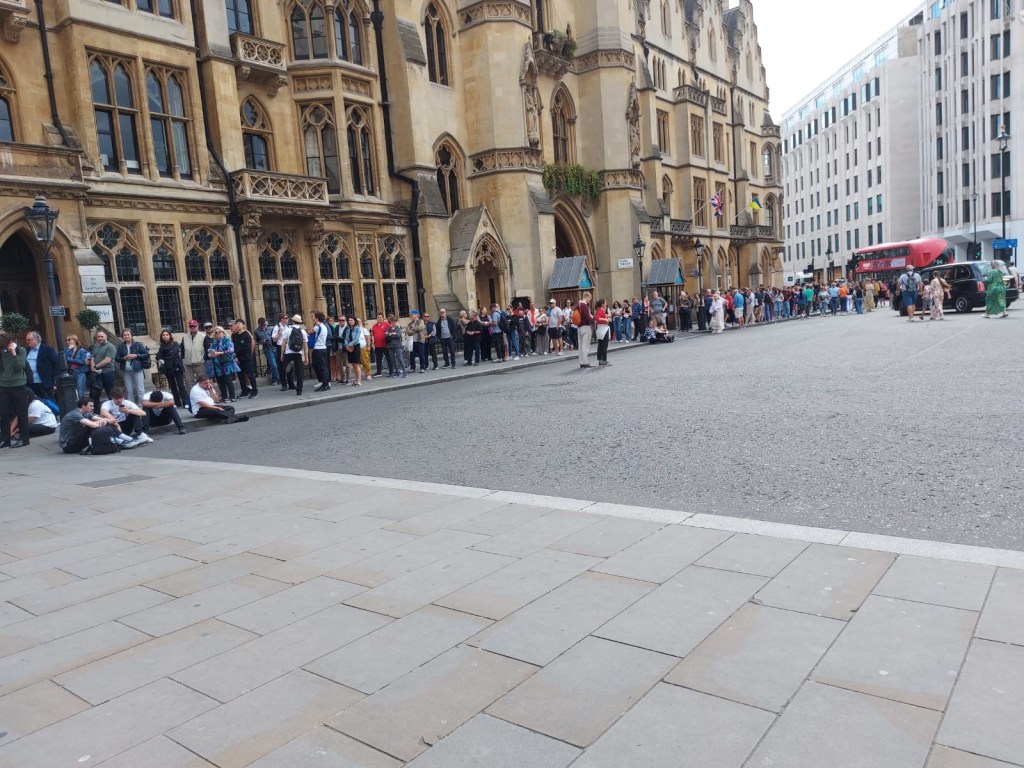

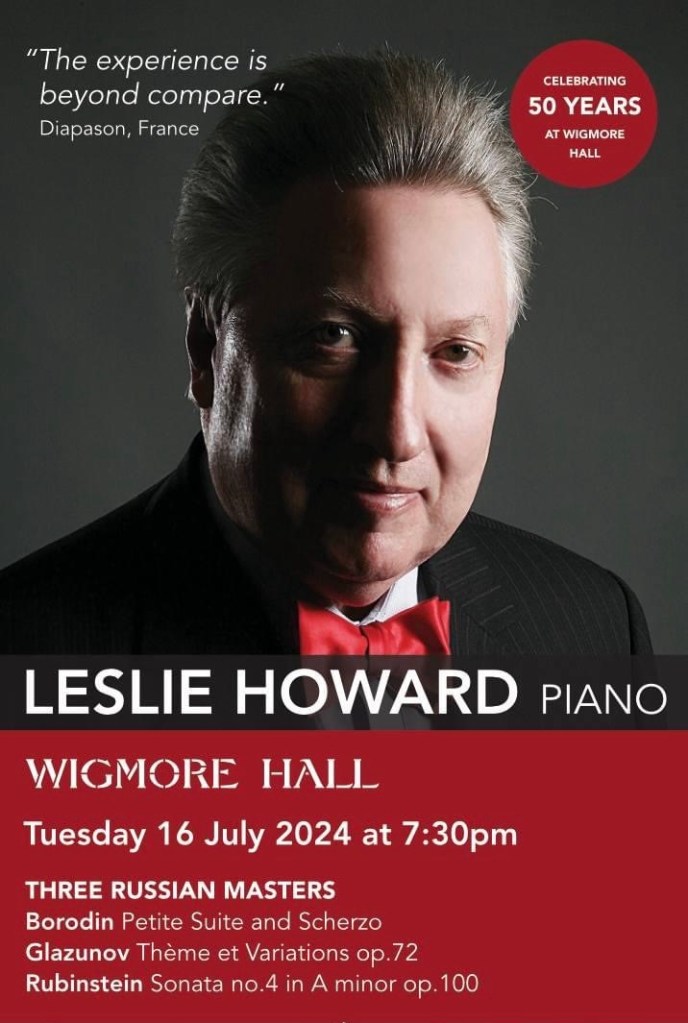

The Wigmore full up with pianists today to greet the Prince of Pianists who has so generously encouraged and supported so many young musicians over the years. It is with the same courage that the most eclectically inquisitive of all pianists presented a programme that none of those pianists has probably heard before .

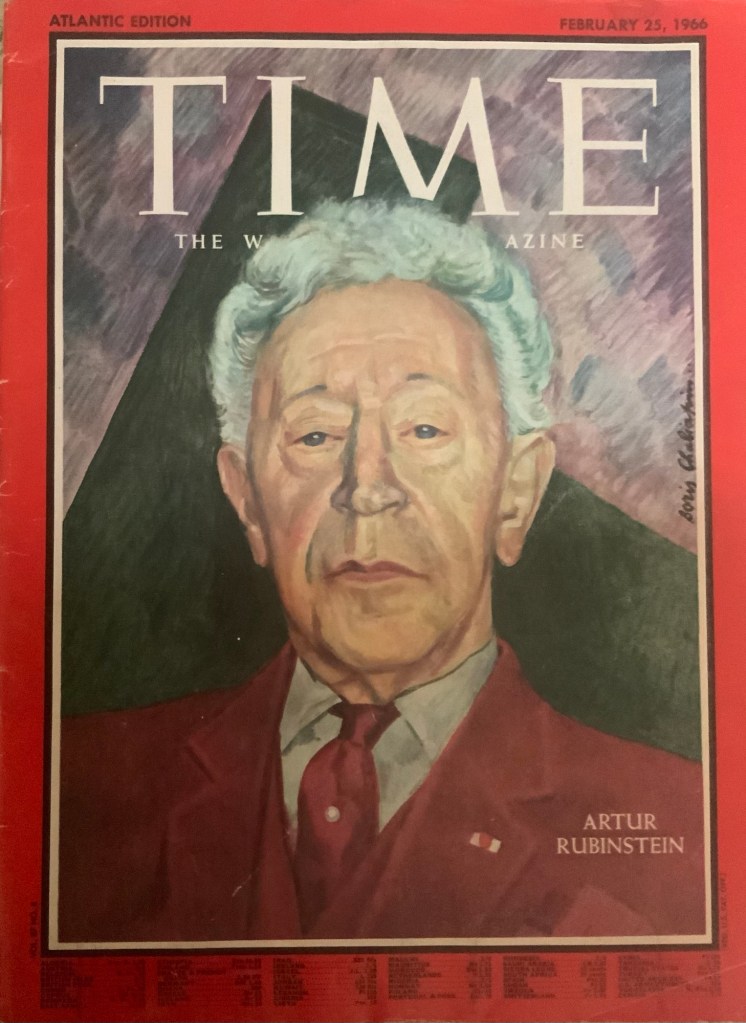

Seated at the piano with Artur Rubinstein’s authority ,hardly moving a muscle but producing a kaleidoscope of sounds that are rarely heard in this hall.A hall that Leslie has played in for the past fifty years and which culminated some years ago in a series of ten Liszt recitals that have gone down in history.

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2023/09/05/milda-daunoraite-at-the-national-liberal-club-sparks-flying-with-refined-piano-playing-of-elegance-and-simplicity/

The world of Liszt and his disciples has been a lifetime’s study and he is even in the Guinness book of records as the only pianist to have recorded all the masters works on over 100 CD’s

I remember a blue eyed,blond Australian who came to Siena to seek out the last disciple of Busoni and a true link to the genius of Liszt.Not the barnstorming Liszt that had been used by virtuosi to show of their wares but the genius who could edit the works of Beethoven as well as creating new forms and visionary new sounds.

Agosti was a very reserved man hard to get close to and with a terror of playing in public.In his studio in Siena, where he held court for the summer months,the sounds that were heard there have never been forgotten .

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2024/01/03/forli-pays-homage-to-guido-agosti/

Agosti immediately realised that he and Leslie had so many things in common but above all a total respect for the composers they were serving.

The extraordinary thing about Agosti’s pianism was that his hands were always close to the keys and with fingers of steel and wrists of rubber he would command his hands to carve out the sounds that he had in his mind and soul.There was a complete lack of unnecessary movement but the range of sounds he could find I have never heard elsewhere.

It was exactly this saving of unnecessary energy that was so noticeable about Leslie’s playing today .

Seated at the piano as in a sumptuous armchair listening attentively as he proceeded to direct the performance like a great conductor before his orchestra.

There was a beauty of sound that even in the most strenuous of passages was never hard or ungrateful.

A range of orchestral colours as he led us through a maze of notes carving out a musical line that was of such clarity and simplicity.

Looking at Leslie’s discography I was astonished to learn that he was one of the first to record all four of Anton Rubinstein’s Sonatas.It was the fourth sonata that was to be the crowning glory of this extraordinary recital filling the entire second half with a work rarely heard in the concert hall even today.

The concert had begun with Borodin’s Petite Suite and Scherzo.A series of six little pieces with the addition of the scherzo which was the only movement that is vaguely familiar.The sombre sounds of the opening ‘Au convent’ were of great resonance with the whispered chant of the nuns of simplicity and purity. Distant and dissonant chimes played with great authority created the atmosphere for this extraordinary work.An ‘Intermezzo’ of a completely different sound world of luminosity and luxuriant melodic outpourings.The ‘Mazurka in C ‘ broke this melancholic atmosphere as it sprung to life with scintillating energy.The ‘Mazurka in D flat’ that followed returned to the languid opening atmosphere with a ravishing tenor melody answered by the soprano voice in a duet of glowing beauty.There was beauty too as the arpeggios gently streamed across the keyboard for a ‘Reverie’ of sumptuous sounds.The gentle pulsating heart beat of the ‘Serenade’ allowed the music to unfold with simplicity and the unmistakable voice of Borodin.The Scherzo ,which Glazunov had added,was played with quixotic drive and scintillating colours interrupted only by the beautiful lyrical ‘Nocturne’ that serves as a Trio in this genial arrangement.

Glazunov’s own Theme and Variations is a large scale work opening with great Russian bells tolling with nobility and creating the atmosphere in which the fifteen variations could evolve.There were etherial sounds of glittering beauty and variations that flowered with sumptuous richness , even a variations that owed much to Brahms.Following on with variations of kaleidoscopic colour and beguiling sounds with streams of notes as the intensity gradually grew.An extraordinary work that Leslie played with an architectural shape and mastery that had us wondering how such an important work could lay hidden from pianists for so long.

The Rubinstein Sonata that Leslie has long been an advocate, is a work of great importance.It has suffered the fate of Rachmaninov’s First Sonata always in the shadow of the Second which was launched in our day by Horowitz and is now overplayed.It has taken Kantarow to show us the way with the First Sonata which is now being taken up by many pianists in the Juilliard School.Listening to Leslie with playing of absolute clarity and authority that gave an architectural shape and above all an overall sound and will open the way for other pianists to follow . There was the same sense of leit motiv in the first movement which can sometimes get submerged by the cascades of notes and chameleonic changes of character that abound .There was a dynamic rhythmic energy to the ‘Scherzo’ and a glorious outpouring of luxuriant melody to the ‘Andante’ with its strange chordal meanderings that Leslie shaped with poignant meaning.There was a relentless forward drive to the ‘Allegro assai’ that just shot from Leslie’s fingers with military precision.Moving inevitably and with scintillating virtuosity to a final melodic climax before the grandiose ending.

A little Barcarolle n.1 by Rubinstein ,played as an encore,showed us the other side of a composer who was a great pianist who could charm and seduce his public also with grace and beauty! I remember being stopped in my tracks as I listened to Rubinstein’s’ Melody in F played with ravishing beauty on the radio – Leslie Howard was the pianist!

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2024/07/16/tyler-hay-at-st-marys-perivale-the-perfect-pianist-comes-of-age/

https://youtube.com/watch?v=kI16VdEWRPU&feature=shared

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2024/04/25/sherri-lun-at-steinway-hall-for-the-keyboard-trust-masterypassion-and-intelligence-of-twenty-year-old-pianist/

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2019/03/27/bobby-chen-in-paradise-andata-e-ritorno/

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2024/05/05/misha-kaploukhii-mastery-and-clarity-in-waltons-paradise-where-dreams-become-reality/

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2024/04/18/mark-viner-at-st-michael-and-all-angels-bringing-mastery-and-discovery-to-chiswick/

Winner of the 2024 ‘Pianos and Soul’ / Amadeus Festival Vienna prize

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2024/02/13/edward-leung-at-st-marys-a-complete-artist-of-maturity-and-stature/

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2023/04/01/victor-maslov-at-cranleigh-arts-a-great-artist-illuminates-and-enriches-our-lives/

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2020/02/29/barenreiter-beethoven-of-jonathan-del-mar/

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2024/06/12/kapellmeister-julian-jacobson-reveals-the-debussy-preludes-at-the-1901-arts-club-with-integrity-and-old-style-musicianship/

12 November 1833, Saint Petersburg – 27 February 1887 Saint Petersburg

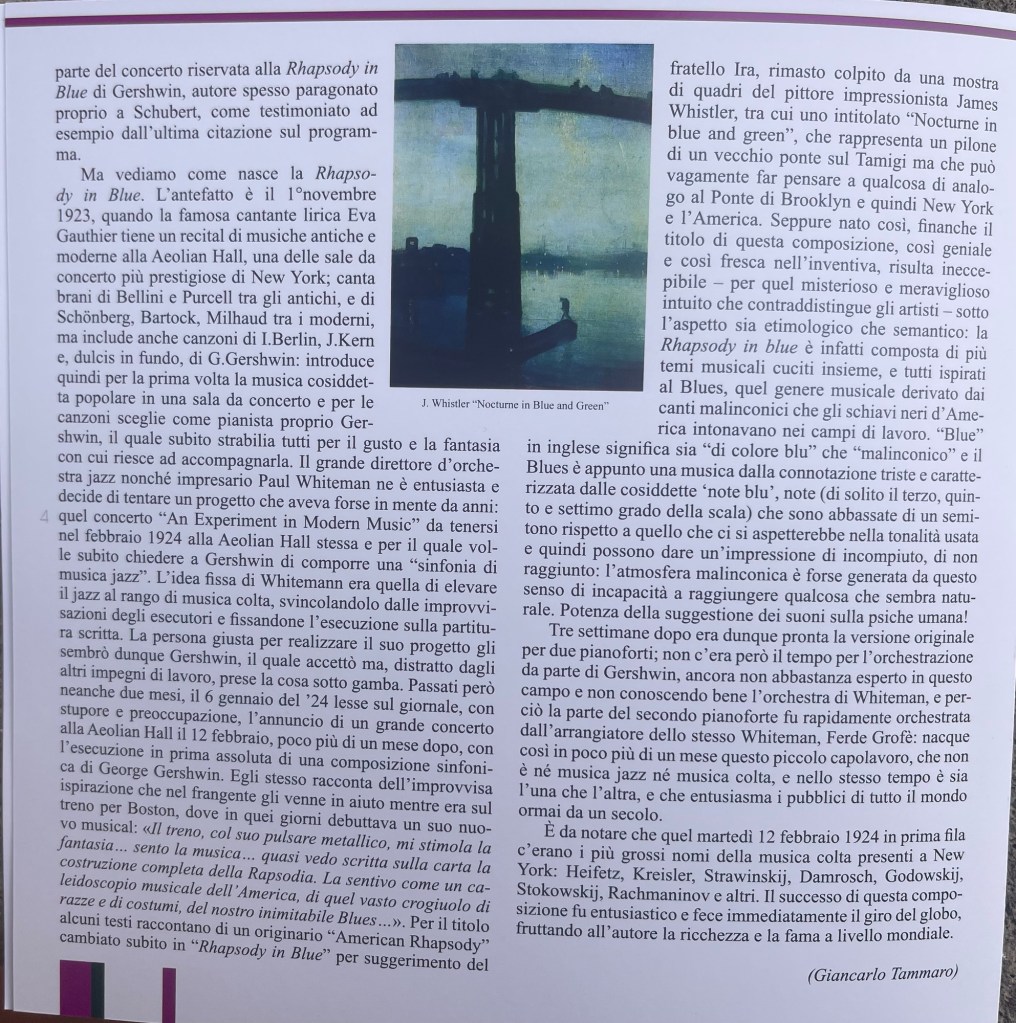

There is one element that looms over this recital of

Russian 19th-century piano music: the so-called ‘Mighty

Handful’ (the term coined by the Russian critic Vladimir

Stasov in 1867). It was a self-appointing group of five

composers dedicated to sustaining Russian national

tradition (initiated by Glinka) at the time of the western European Romanticism of Liszt, Berlioz and

Wagner. The original group had gathered around Balakirev (1837-

1910), in the early 1860s, and included Aleksandr Borodin,

the illegitimate son of a Georgian noble. A doctor and chemist by profession and training, Borodin made important early contributions to organic chemistry and regarded medicine and science as his primary occupations, only practising music and composition in his spare time or when he was ill.As a chemist, Borodin is known best for his work concerning organic synthesis and was a promoter of education in Russia founding the School of Medicine for Women in Saint Petersburg, where he taught until 1885.

Balakirev took him under his wing in 1862, pushing him towards more overtly Russian, large-scale work notably his only opera Prince Igor (a

historic epic like Musorgsky’s Boris Godunov or Glinka’s A

Life for the Tsar). But, as with other works by him, and to the

increasing frustration of his fellow musicians, Prince Igor

kept Borodin fitfully occupied for the rest of his life and was completed posthumously by Rimsky-Korsakov and Glazunov

Borodin did, however, find time in 1885, near the end of his

life, to return to the small scale in which he felt more

confident. His fame outside Russia was made possible during his lifetime by Liszt , who arranged a performance of the Symphony No. 1 in Germany during 1880, and by the Comtesse de Mercy- Argenteau in Belgium and France. His music is noted for its strong lyricism and rich harmonies. Along with some influences from Western composers, as a member of The Five, his music is also characteristic of the Russian style where his passionate music and unusual harmonies proved to have a lasting influence on the younger French composers Debussy and Ravel (in homage, the latter composed during 1913 a piano piece entitled “À la manière de Borodine”).

The draft of the suite met with approval from Liszt, to whom

Borodin showed the work in Weimar that summer; they had

first met several years earlier, on which occasion Liszt’s

advice to him had been uncompromising: ‘Work in your own

way and pay no attention to anyone’.

The Petite Suite is a suite of seven piano pieces, written by Alexandr Borodin , and acknowledged as his major work for the piano. It was published in 1885, although some of the pieces had been written as far back as the late 1870s.After Borodin’s death, Alexandr Glazunov orchestrated the work, and added his orchestration of another of Borodin’s pieces as an eighth number.

The suite was dedicated to the Belgian Countess Louise de Mercy-Argenteau , who had been instrumental in having Borodin’s First Symphony performed in Verviers and Liège. She had also arranged for French translations of some of his songs and excerpts from Prince Igor ; and had initiated the sponsorship of Camille Saint-Saens and Louis- Albert Bourgault-Ducoudray -Ducoudray for Borodin’s membership of the French Society of Authors, Composers and Editors.

Borodin’s original title for the work was Petit Poème d’amour d’une jeune fille (“Little poems on the love of a young girl”), but by publication time the name Petite Suitehad been applied to it.

The original suite consisted of the following 7 movements, with descriptions supplied by the composer:

- Au couvent, Andante religioso, C-sharp minor (“The Church’s vows foster thoughts only of God”)

- Intermezzo, Tempo di minuetto, F major (“Dreaming of Society Life”)

- Mazurka I, Allegro, C major (“Thinking only of dancing”)

- Mazurka II, Allegretto, D-flat major (“Thinking both of the dance and the dancer”)

- Rêverie, Andante, D-flat major (“Thinking only of the dance”)

- Serenade, Allegretto, D-flat major (“Dreaming of love”)

- Nocturne, Andantino, G-flat major (“Lulled by the happiness of being in love”).( Later to become the Trio of the added Scherzo)

After Borodin’s death in 1887, Alexander Glazunov orchestrated the suite, but incorporated into it another piano piece by Borodin, the Scherzo in A flat , and slightly rearranged the order of the pieces.

- Au couvent

- Intermezzo

- Mazurka I

- Mazurka II

- Rêverie

- Serenade

- Finale: Scherzo (Allegro vivace, A-flat major) – Nocturne – Scherzo ( the original nocturne becoming the Trio of the added Scherzo)

https://youtube.com/watch?v=IepGv-kJPJ0&feature=shared

Alexander Konstantinovich Glazunov

10 August 1865 Saint Petersburg – 21 March 1936 Neuilly-sur-Seine

As a teenager, Aleksander Glazunov was steered by

Balakirev to study with Rimsky-Korsakov (also one of the

Mighty Handful), although by then (the early 1880s)

Balakirev’s mantle had been assumed by the philanthropist,

publisher and patron Mitrofan Belyayev, who promoted his

young protégé around western Europe, including arranging

meetings with Liszt and Wagner.

Glazunov made his conducting debut in 1888. The following year, he conducted his Second Symphony in Paris at the World Exhibition.He was appointed conductor for the Russian Symphony Concerts in 1896. In 1897, he led the disastrous premiere of Rachmaninov’s Symphony n. 1 which led to Rachmaninoff’s three-year depression. The composer’s wife later claimed that Glazunov seemed to be drunk at the time , according to Shostakovich, kept a bottle of alcohol hidden behind his desk and sipped it through a tube during lessons.

Drunk or not, Glazunov had insufficient rehearsal time with the symphony and, while he loved the art of conducting, he never fully mastered it.Glazunov toured Europe and the United States in 1928,and settled in Paris by 1929. He always claimed that the reason for his continued absence from Russia was “ill health”; this enabled him to remain a respected composer in the Soviet Union. He wrote three ballets; eight symphonies and many other orchestral works; five concertos (2 for piano; 1 for violin; 1 for cello; his last work was a concerto for saxophone); seven string quartets; two piano sonatas and other piano pieces; miscellaneous instrumental pieces; and some songs. He also collaborated with the choreographer Fokine to create the ballet Les Sylphides, a suite of music by Chopin orchestrated Chopin by Glazunov.

Theme and Variations, Op 72, which uses as the theme for fifteen variations the same folk-song as Glazunov’s later Finnish Fantasy for orchestra. The work was written in the same year as the first piano sonata and is undoubtedly one of Glazunov’s most successful forays into the piano medium.Glazunovs Theme and variations, Op 72, was written in 1900 and is one of three large-scale works for piano (the others being his two sonatas) completed during his last significant period as a composer1899 to 1906. Originally given the title Variations on a Finnish Folk Song, The work comprises a theme and fifteen variations

Anton Grigoryevich Rubinstein

28 November 1829 Ofatinți Moldova – 20 November 1894 Saint Petersburg

His resemblance to Beethoven was much remarked upon – Liszt referred to Rubinstein as “Van II.” This resemblance was also felt to be in Rubinstein’s keyboard playing. Under his hands, it was said, the piano erupted volcanically. Audience members wrote of going home limp after one of his recitals, knowing they had witnessed a force of nature.When caught up in the moment of performance, Rubinstein did not seem to care how many wrong notes he played as long as his conception of the piece he was playing came through.Rubinstein himself admitted, after a concert in Berlin in 1875, “If I could gather up all the notes that I let fall under the piano, I could give a second concert with them.”

Part of the problem might have been the sheer size of Rubinstein’s hands. Josef Hofmann ,his only private pupil ,noted that Rubinstein’s fifth finger “was as thick as my thumb—think of it! Then his fingers were square at the ends, with cushions on them. It was a wonderful hand.”

As a child prodigy he had played for Chopin and Liszt who refused to take him on as a pupil.He toured throughout Europe and the

United States as the first great international Russian pianist .Engaged by Steinway & Sons, Rubinstein toured the United States during the 1872–73 season. Steinway’s contract with Rubinstein called on him to give 200 concerts at the then unheard-of rate of 200 dollars per concert (payable in gold—Rubinstein distrusted both United States banks and United States paper money), plus all expenses paid. Rubinstein stayed in America 239 days, giving 215 concerts—sometimes two and three a day in as many cities.

Rubinstein wrote of his American experience,

‘May Heaven preserve us from such slavery! Under these conditions there is no chance for art—one simply grows into an automaton, performing mechanical work; no dignity remains to the artist; he is lost… The receipts and the success were invariably gratifying, but it was all so tedious that I began to despise myself and my art. So profound was my dissatisfaction that when several years later I was asked to repeat my American tour, I refused pointblank…’

Like Liszt, Rubinstein was a prolific composer – his works

include six symphonies, five piano concertos, many solo

works for piano and 20 operas, among them The Demon,

which is still on the fringes of the repertoire – and he

founded the St Petersburg Conservatoire in 1862 (where

Glazunov later was also director).

Hans von Bülow describe him as

the ‘Michelangelo of music’ – and these qualities define his

last Piano Sonata, No. 4 in A minor Op. 100. The first three

were composed in the late 1840s and early 1850s, with a gap

of 25 years before No. 4 appeared around 1880. In his own words he described himself thus :

‘Russians call me German, Germans call me Russian, Jews call me a Christian, Christians a Jew. Pianists call me a composer, composers call me a pianist. The classicists think me a futurist, and the futurists call me a reactionary. My conclusion is that I am neither fish nor fowl—a pitiful individual.’

Leslie Howard writes for his recordings on Hyperion of the Rubinstein Fourth Sonata :

‘In the more than a quarter of a century which separates the third from the fourth of the Rubinstein sonatas (the fourth appeared in 1880) lie only two of his major works for piano—the Fantasy, Opus 77, and the Theme and Variations, Opus 88, both of which are larger than any of the earlier sonatas and show a very different weight of thought from the dozens of character pieces which otherwise fill the Rubinstein piano œuvre. The fourth sonata turns out to be in this grand mould, on a much broader scale than the others, and is almost leisurely in its expansiveness.

There are two parts to the first theme of the Moderato con moto: a strong rhythmic motif marked appassionato e con espressione and a gentler rising theme accompanied by triplet chords. An animated transition passage leads to the second group of themes: a lyrical melody which is immediately extended and developed, and a codetta which contains two more melodic ideas, the second of which introduces the development after the exposition is repeated. All the themes other than the lyrical second subject play a part in the development, and the opening theme is treated fugally. The regular recapitulation is rounded off with a short coda.

The scherzo is a very powerful affair whose skittish moments are generally interrupted by gruff cadences on the off beats, and there is some occasional mildly experimental dissonance. The calmer trio section curiously calls to mind the Grieg of the Lyric Pieces, with its two-bar phrases and delicate syncopations.

The slow movement is very generous with melody—the exposition contains seven distinct themes, three in the home key of F major before a more animated theme in 5/8 introduces D flat. A modulatory theme leads to the second subject and codetta in C major. Development is confined to the first of the themes, but the recapitulation introduces many variations in texture and tonality. A second development turns out to be a long valediction on the first subject group.

The finale is a very busy moto perpetuo with a theme appearing in octaves in the bass before it undergoes the first of many transformations. A brief attempt at a lyrical second theme is doomed by the insistent return of the first for development, but a more expressive section intervenes before the recapitulation, in which the second subject finally takes wing before precipitating headlong into the conclusion.’ Dr Leslie Howard

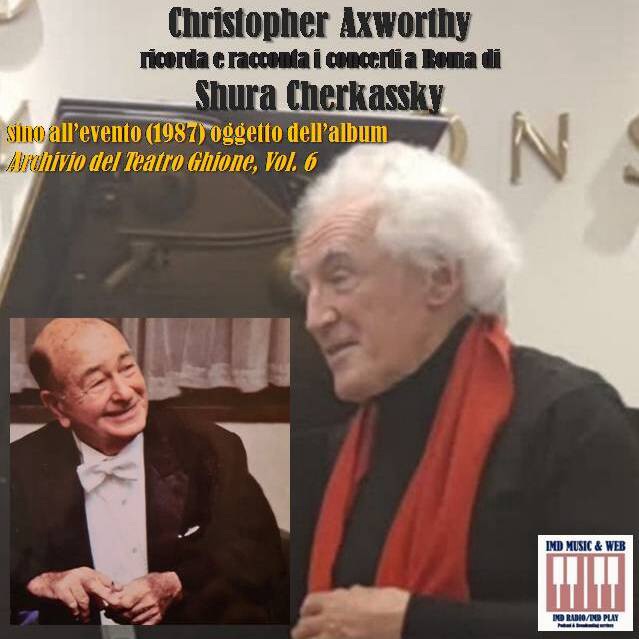

Leslie Howard 75th Birthday Concert ‘An experience beyond compare’- The true heir to Agosti – Busoni -Liszt

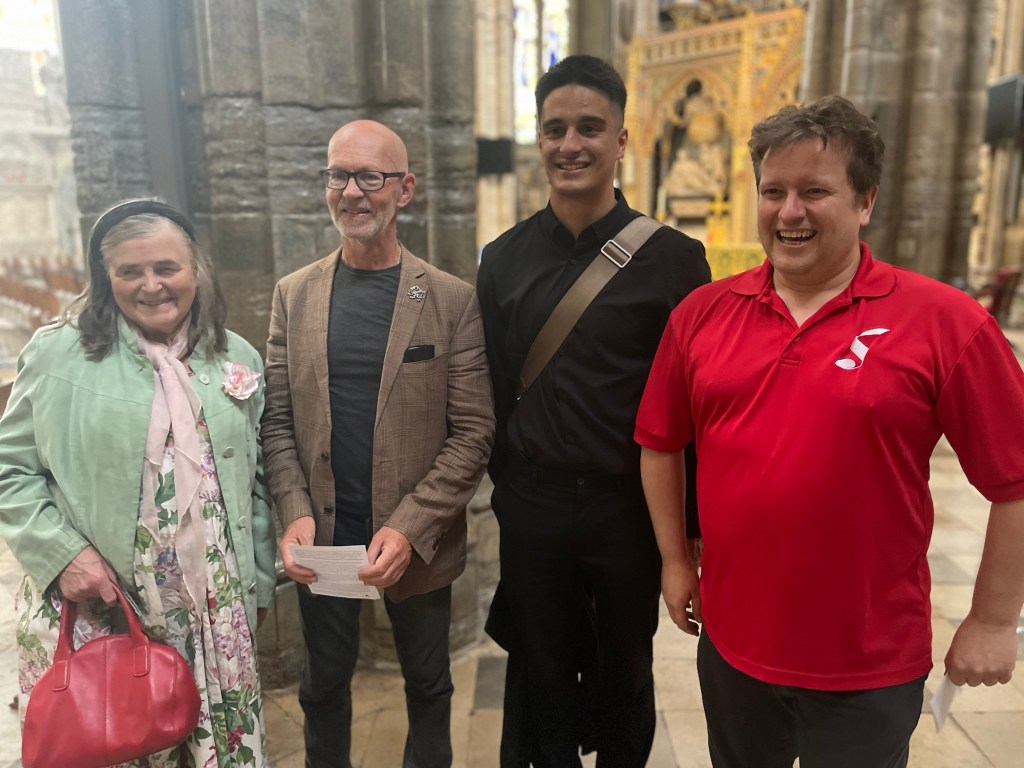

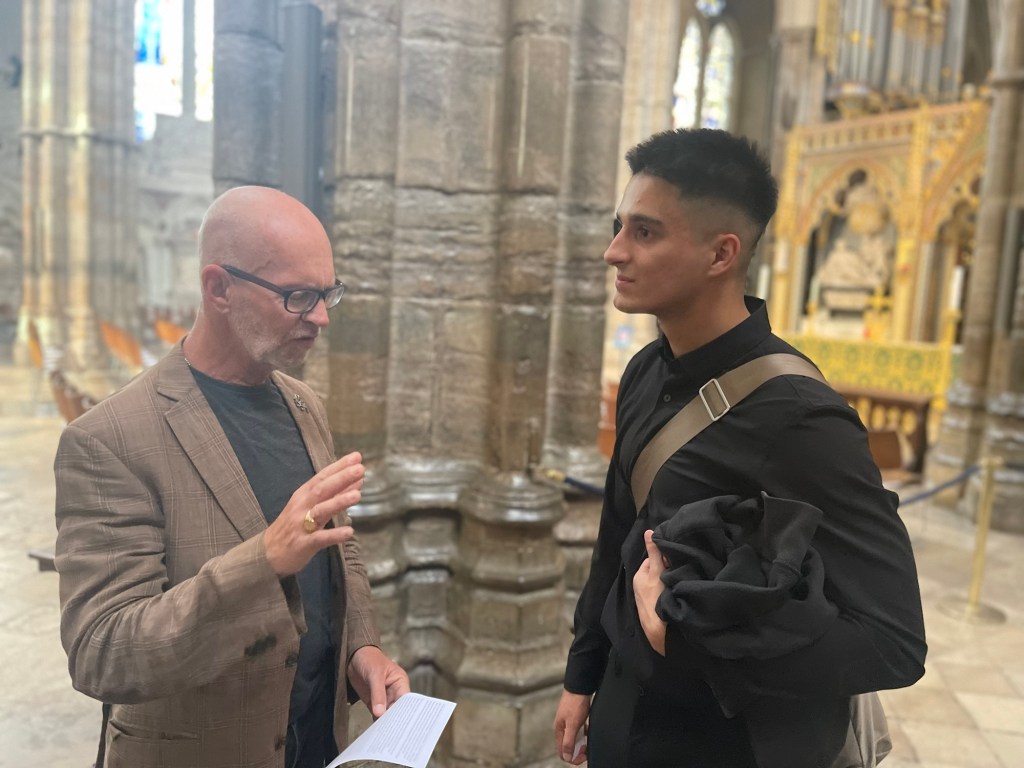

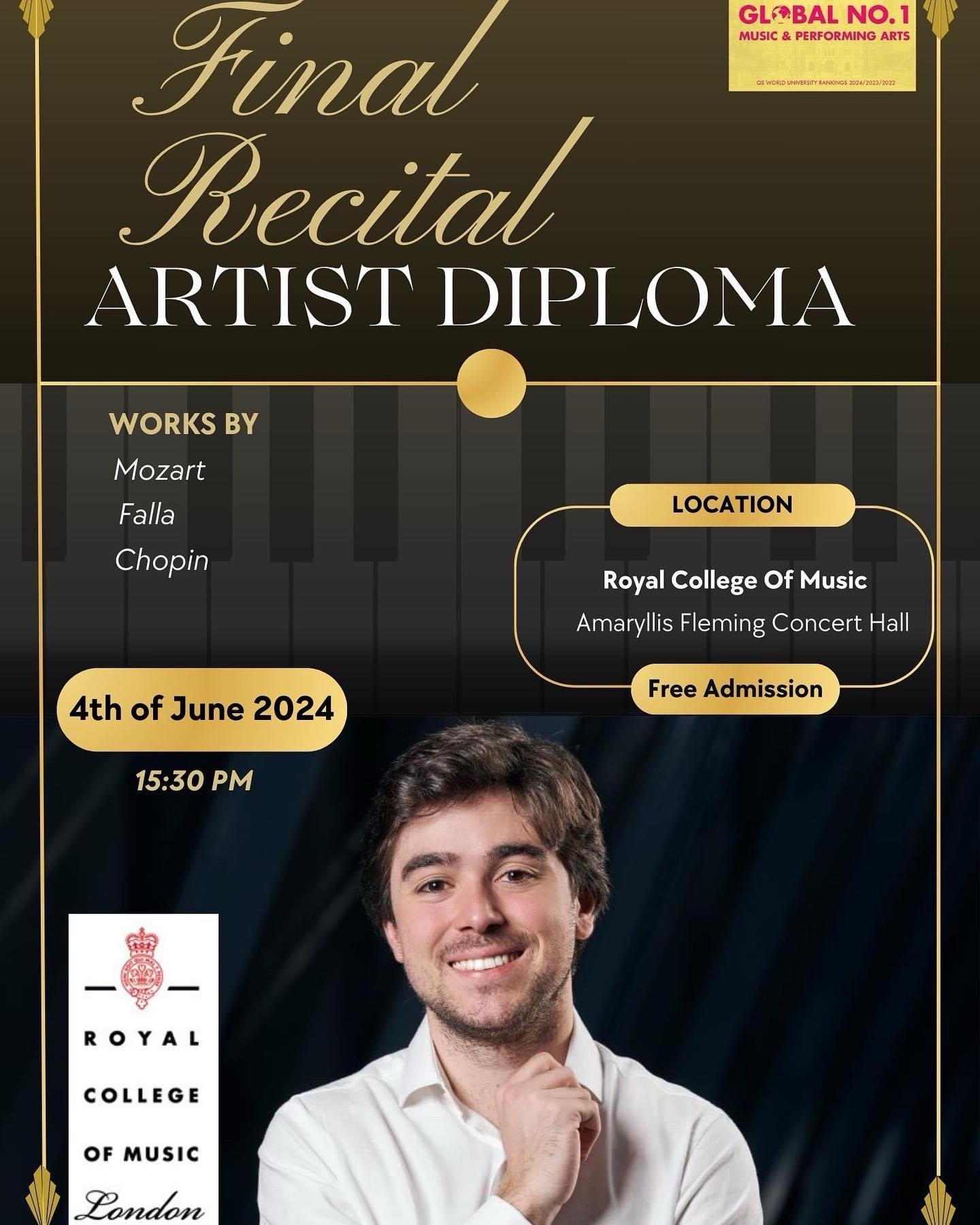

Leslie Howard Masterclass at the R.C.M Scholarship and Mastery shared