Domenica 10 novembre ore 12; Museo Pietro Canonica

Le parafrasi da concerto di Franz Liszt da Verdi

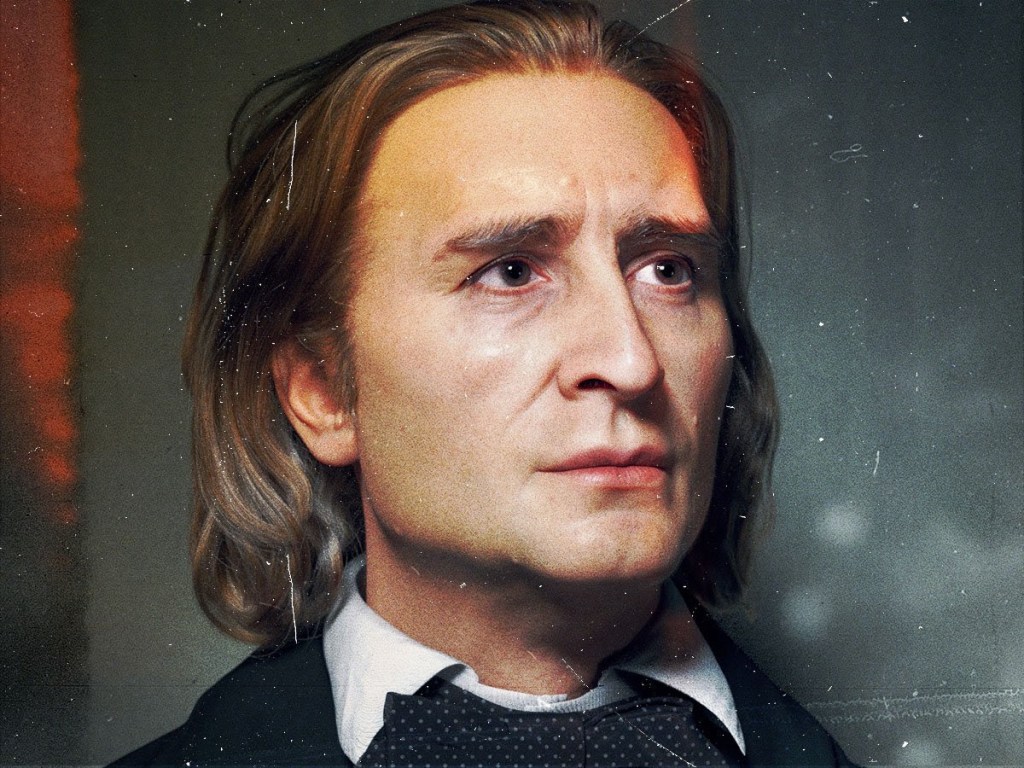

FRANZ LISZT

22 October 1811 Doborjan Kingdom of Hungary, AustrianEmpire

31 July 1886 (aged 74) Bayreuth , Kingdom of Bavaria, German Empire

R. Wagner – F. Liszt: Isoldes Liebestod, S. 447

Domenico Bevilacqua, pianoforte

G. Verdi – F. Liszt: Ernani. Parafrasi da concerto, S. 432; Miserere dal Trovatore, S. 433; Salve Maria! Da Jérusalem (I Lombardi), S. 431ii ; Don Carlos. Coro di festa e marcia funebre, S. 435; Aida. Danza sacra e duetto finale, S. 436; Reminiscenze di Simon Boccanegra, S. 438; Rigoletto. Parafrasi da concerto, S. 434

Giovanni Bertolazzi, pianoforte

Sensational is the only word to describe Giovanni Bertolazzi playing all seven of the opera paraphrases of Verdi by Liszt

Presenting his student ,Domenico Bevilacqua, opening with Liebestod which had all the colours and musicianship of his mentor

But when Giovanni struck up the Ernani paraphrase there was a authority and breathtaking presence that was to hold a museum packed to the rafters mesmerised by such artistry on this sunny Sunday morning in Villa Borghese they even demanded more and Giovanni very generously offered three encores. A little waltz written for piano by Puccini ; De Falla’s Ritual Fire Dance alla Rubinstein ! And by even great insistence Valse Triste by the violinist Vecsey (Agosti was often his duo partner) in the spectacular arrangement for piano by Cziffra.

A triumph and it is thanks to Valerio Vicari who had spotted his talent a few years ago and has brought his talent to the fruition that is being applauded worldwide today.

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2022/01/17/giovanni-bertolazzi-in-rome-liszt-is-alive-and-well-at-teatro-di-villa-torlonia/

Today Domenico showed a depth of sound from the arresting opening chords that were played with strength but never hardness.A kaleidoscope of colours allowed the twisting and turning of the counterpoints to entwine with fluidity and glowing beauty as they built to a passionate climax only to die away to a magical whisper. A superb sense of style and stretching the insinuating sounds to their maximum without ever loosing sight of the overall architectural shape.

Liszt made a concert paraphrase of Ernani in 1847, but this remained unpublished. A second Paraphrase de concert was made in the following years and revised in 1859. The opera itself was first staged in Venice in 1844 and deals with the rivalry for the love of Elvira of the bandit Ernani and Don Carlo, King of Spain, complicated by the implacable hostility of Elvira’s uncle, Don Ruy Gomez, who conspires with Ernani against the King. When matters seem resolved, Don Ruy gives a signal, agreed with Ernani, that the latter should die, if Don Ruy demands it. The signal is given, and Ernani stabs himself. The third act is set in a cathedral vault at Aix-la-Chapelle, before the tomb of Charlemagne. Don Carlo, who is to be elected Holy Roman Emperor, overhears the conspirators, turns and addresses his illustrious predecessor in O sommo Carlo (O supreme Carlo), and extends clemency to Ernani and Elvira. It is this melody that provides the basis of Liszt’s paraphrase.

First staged in Rome in 1853, Il trovatore has a plot of some complexity. The troubadour of the title, Manrico, is the supposed son of the gypsy Azucena, but actually the stolen child of the old Count di Luna, a rebel and declared enemy of the young Count di Luna. Both are in love with Leonora, and Manrico, in his stronghold, is preparing to marry her, when news comes of the imminent death of his supposed mother, taken by the Count and condemned to death by burning. In his attempt to save her, Manrico is taken prisoner by the Count. In the fourth act Leonora, brought to a place outside Manrico’s prison, thinks to bring him new hope. From the tower the Miserere is heard, Miserere d’un’ alma già vicina / Alla partenza che non ha ritorno! (Have mercy on a soul already near / To the parting from which there is no return). Leonora’s horrified exclamation, Quel suon, quelle preci solenni, funeste (What sound, what solemn, mournful prayers) leads to Manrico’s Ah che la morte ognora / È tarda nel venir (Ah how slow the coming of death), from the tower, his farewell to his beloved. Once again Liszt has chosen the point of highest tragedy for his 1859 paraphrase. It is followed by Leonora’s offer of herself to the Count, in return for her lover’s release, having secretly taken poison, her death, and that of Manrico, executed, but now finally revealed by Azucena to the Count as his own brother.

Verdi’s opera of 1842, I Lombardi was recast in 1847 for Paris as Jérusalem. The Paris version transposes the action from Lombardy to France. The prayer, sung by Hélène, daughter of the Count of Toulouse, who has killed her lover’s father, again comes in the first act. Liszt’s version, more transcription than paraphrase, made originally in 1848, is dedicated to Madame Marie Kalergis, née Comtesse Nesselrode. The tremolo effect, originally for violins, is preserved in Liszt’s version, more particularly, perhaps, in the alternative transcription for the newly invented armonipiano, with its tremolo pedal.

Dating from 1867-68, Liszt’s treatment of the Coro di festa e marcia funebre from Don Carlos is based on the opera of that name, first seen in its original version in Paris in 1867. Drawn from Schiller’s dramatic poem, the plot centres on the Spanish Infante, son of Philip II, and his love for Elisabeth de Valois, originally his betrothed but then the wife of the King. The involvement of Don Carlos with rebels in Flanders and the interventions of Princess Eboli, who is also in love with Don Carlos, bring further complications, ending in his condemnation and final mysterious rescue into the monastery founded by his grandfather, from behind whose tomb a voice calls him. The Church has an important part to play and the Grand Finale of the third act brings a popular celebration, in front of the Cathedral of Valladolid, honouring the King. This spectacular scene is followed by a funeral march, as monks escort heretics to their deaths at the stake.

Verdi wrote his Egyptian opera Aida for the opening of the Cairo Opera House in 1871. Aida, daughter of the King of Ethiopia but enslaved by the Egyptians, is in love with Radames, appointed captain of the Egyptian armies in their fight against the Ethiopians. Victorious in battle, Radames is promised the hand of Aida’s mistress, Amneris, daughter of the King of Egypt, as a reward for his triumph. In an assignation with Aida, whom he loves, he divulges military secrets to her, overheard by her father, a prisoner of the Egyptians. Accused of treachery, Radames is condemned to death, to the dismay of Amneris, and, immured in a tomb, he is joined by Aida, allowing the two to die together, while Amneris mourns the fate of her beloved Radames. Liszt offers a paraphrase of the Danza sacra e duetto final,published in 1879. The sacred dance, from the end of the first act, accompanies the reception by Radames of the sacred sword, the symbol of his army command. Priestesses in the temple chant their prayer to the god Phtha, Possente, possente Phtha!, followed by their dance. In the fourth act the chant of the priestesses in the temple is heard, as Radames and Aida, entombed below, bid farewell to life in O terra addio, o valle di pianti (O earth, farewell, O vale of tears, farewell), and Amneris, distraught, offers her own prayer.

Liszt’s Réminiscences de Boccanegra was written in 1882, a year after Verdi’s revision of his 1857 opera. It deals with events in medieval Genoa, plots against the Doge, Simone Boccanegra, and the machinations of the goldsmith Paolo Albiani. The opera ends with the death of Boccanegra, poisoned by Paolo, but the happy joining together of his daughter Amelia with Gabriele Adorno, who succeeds Boccanegra as Doge. Liszt’s reminiscences start with a reference to the 1881 Prologue, in which the election of Boccanegra as Doge is proposed. This leads to the final chorus of the second act, All’armi, o Liguri (To arms, O Ligurians), a popular rebellion against the Doge, that is to be defeated. A further reference is to the final ensemble of the third act, bringing the death of Boccanegra, but otherwise general reconciliation. Liszt ends the work with a return to the theme of the Prologue.

Liszt’s concert paraphrases, are more than mere transcriptions, offering a re-interpretation based on thematic material drawn from their source. Among the best known of his Verdi arrangements is his Rigoletto Paraphrase de concert, written in 1859. Verdi’s opera had had its first performance in Venice in 1851. The plot centres on the court jester of the title, a servant and accomplice of the Duke of Mantua in his amorous adventures. Cursed by a courtier whose daughter the Duke has dishonoured, Rigoletto suffers the loss of his own daughter, Gilda, seduced by the Duke and then abducted, for the Duke’s pleasure, by the courtiers. In the last act of the opera Rigoletto has hired an assassin, Sparafucile to murder the Duke as he dallies with Sparafucile’s sister, Maddalena. They are observed from the darkness outside by Rigoletto and his daughter, who is to die at the assassin’s hands. It is this final scene that Liszt takes as the basis of his paraphrase. The theme that dominates is the Duke’s Bella figlia d’amore (Fair daughter of love), interspersed with the light-hearted replies of Maddalena, and the exclamations of Gilda, as she sees her lover’s infidelity exposed.

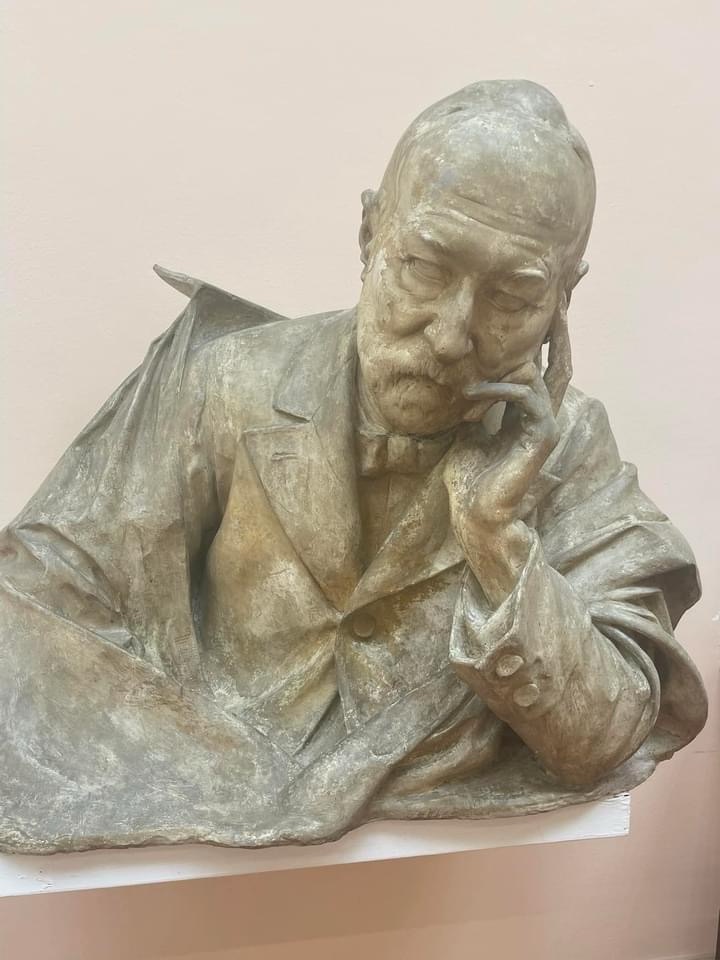

Franz Liszt compose diverse parafrasi da concerto su opere di Giuseppe Verdi, trascrizioni virtuosistiche ed elaborate, basate su celebri melodie da opere verdiane. Questi brani rappresentano non solo una forma di omaggio da parte di Liszt a Verdi, ma anche un’opportunità per il compositore ungherese di esplorare nuove possibilità tecniche ed espressive al pianoforte. Tra le più famose troviamo le parafrasi tratte da “Rigoletto”, “Il Trovatore” e “Aida”. Liszt prende i temi più drammatici o lirici delle opere e li rielabora con una scrittura pianistica virtuosistica e ricca di colori, che esalta sia le qualità tecniche del pianista che la forza emotiva della versione originale. Le parafrasi non si limitano a una semplice trascrizione: Liszt interviene trasformando, espandendo e rielaborando i temi, creando nuove opere che stanno in equilibrio tra la fedeltà al modello e l’innovazione personale.

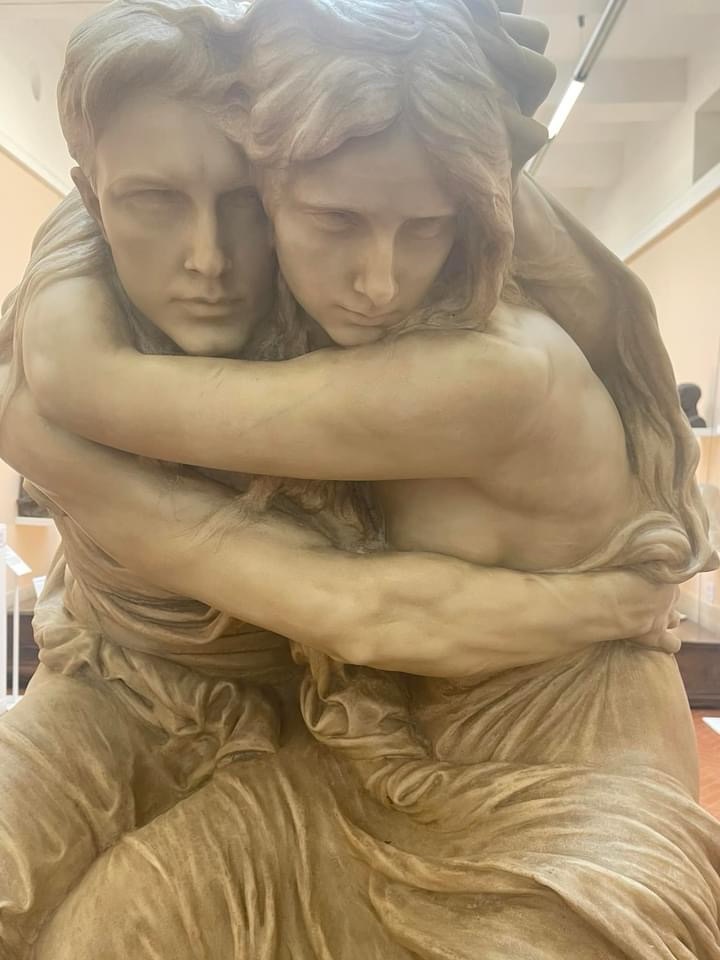

La morte di Isotta, scena finale del “Tristano e Isotta” di Wagner, è una delle trascrizioni più celebri di Liszt. In questa parafrasi, Liszt trasforma il celebre “Liebestod” di Isotta in un capolavoro pianistico che evoca con grande intensità il senso di estasi e di annullamento amoroso che caratterizza la scena finale dell’opera. La trascrizione riflette la profondità tragica e mistica del dramma wagneriano, mantenendo l’intensità emotiva dell’originale, ma trasponendola in una dimensione intima e pianistica.

Matvienko -Bertolazzi – Borgato in Florence and the season opens with a triumph

Giovanni Bertolazzi triumphs on the Keyboard Trust tour of USA October 2023 Virginia-Washington-Philadelphia- Delaware – New York

https://breraplus.org/en/story/clive-britton/

Giovanni Bertolazzi -Homage to Zoltan Kocsis A giant returns to celebrate a genius

Giovanni Bertolazzi Liberal Club ‘En Blanc et Noir’ 5th June 2023 ‘A star is born!’

Roberto Prosseda will present his ‘Composers of the Roman School’ in the Museo Carlo Bilotti on Saturday 30th Novembre at 12.00 – A programme he recently presented with his Rovigo Academy in New York

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2021/01/13/roberto-prosseda-pays-tribute-to-the-genius-of-chopin-and-the-inspirational-figure-of-fou-tsong/

Giovanni Bertolazzi at the Quirinale A kaleidoscope of ravishing sounds that astonish and seduce for the Genius of Liszt

Giovanni Bertolazzi – “A Giant amongst the Giants”