Lovely Milda as Dr Mather says ‘Alive and captivating with her charismatic and charming personality that is what comes across in her playing’.

From an almost too serious Schubert but with ravishing glimpses of paradise that shone through as it did with Chopin’s Fourth Scherzo with brilliant playing of breathtaking beauty and vitality. An all or nothing performance of Liszt’s Dante Sonata had us all on the edge of our seats as demonic octaves were calmed with whispered secrets of sublime beauty.Finally a cat and mouse study by Ligeti that just showed off her brilliant technical command as the wind blew so securely over the keys in her beautiful hands.What is it about these pianists from Lithuania that have a freshness and fluidity of playing that is like a breath of fresh air blowing especially on this winters day in Perivale!

A truly joyous opening to the Schubert Sonata that she played with great rhythmic drive but also with poetic sensibility knowing that this Beethovenian opening would soon dissolve into the most etherial mellifluous sounds before the startling call to arms of the development.Some magical sounds and deeply felt playing of exquisite poetry where Schubert’s whispered asides spoke so deeply to this very sensitive young artist. Always with a radiance of sound whether loud or barely audible there was a fluidity and glow of vibrancy to everything she played. Moments of almost Schumannesque changes of mood were played with great style and character as the music was allowed to speak simply and directly. It was the same ravishing sound that she brought to the ‘Allegretto’ where the beautiful theme that Schubert was to use again in his penultimate sonata was floated on a light staccato accompaniment that Milda played with transcendental control of sound .The capricious ‘Allegro vivace ‘ of the last movement was played with a question and answer of beguiling charm and beauty where Schubert’s inevitable bursting into song was tinged with bitter sweet melancholy.

The Chopin Fourth Scherzo demonstrated Milda’s superb technical control with not only brilliantly agile fingers but her whole body that followed the flow of the music with enviable naturalness and simplicity. Feather like precision but limpet like tenacity gave great shape to the fleeting changes of mood that unusually invade Chopin’s works in this final period of his life .The expansive central episode was allowed to unfold on a gentle wave of subtle emotions of ravishing beauty and intoxicating perfumed sweetness. A masterly build up of changing harmonies as Chopin finds his way back to the capricious silf like scherzo, awakening from a momentary apparition of miraculous beauty . Milda played the final pages with aristocratic authority and passionate involvement where the grandiosity of the final joyous outpouring was played out with sumptuous golden sounds of richness and nobility.

There was a suitably dramatic opening to the Dante Sonata but also a very subtle palette of colours which enabled Milda to open a window on a work that she was to depict so grafically, as barely whispered gasps led us into an underworld of terrifying vibrancy and desperation .Cascades of octaves that were streams of sounds in Milda’s poetic hand – never percussive but full and with a sense of direction as they strode across the keys with fearless abandon.She brought a glowing beauty to the Andante which as Liszt suggests was finding its way to the barely whispered confessions that the composer marks ‘pianississimo dolcissimo con amore’ and indeed could not have found a more sensitive artist to turn his deepest thoughts into sounds. Gradually unwinding like in the Chopin Scherzo after a magical oasis gave way to a drama that was to be played out in Liszt’s case with outpourings of transcendental difficulty, not least the treacherous final leaps that Milda threw off with mastery as she was living the story right to the final anguished chords deep in the underworld of the piano.

I remember Shura Cherkassky pulling out an old BBC copy of a Ligeti Study that he had programmed for the following season .He liked to add a new contemporary work to his repertoire every year and after Rodney Bennet studies and El Salon Mexico by Copland,in the past years,it had fallen to ‘L’escalier diabolique’ the 13th of Ligeti’s eighteen studies.I think Shura chose it for the title and he asked Connie and I to teach it to him whilst holidaying with us in my seaside home in Italy!

Milda had chosen the sixteenth ‘Pour Irina’ with its long drawn out opening that she played with a purity and clarity before her hands took off on their journey of a moving web of sounds .One can almost compare this to the last movement of Chopin’s Funeral March Sonata which was described by Schumann as :”more like a mockery than any sort of music”, Mendelssohn asked for an opinion, simply stated that he ‘abhored it’. Milda played it with the score and was totally involved in the intricacies that she commanded her agile fingers to carve out with rhythmic drive and precision giving the notes a life of their own that was certainly no mockery!

Lithuanian pianist, Milda Daunoraite , began her piano studies at the age of six. She received her formative education at The Purcell School of Music and is currently studying with Tessa Nicholson at the Royal Academy of Music, on a full fees scholarship, where she is a recipient of the ABRSM Scholarship Award. She is supported by The Keyboard Charitable Trust, ‘SOS Talents Foundation – Michel Sogny’ and the Mstislav Rostropovich Foundation.

Milda’s performances have been featured live in forty countries through Mezzo TV, Radio Classique, TV5 Monde and Lithuanian National Television and Radio. In 2018, Milda performed the Fourth Piano Concerto by V. Bacevicius for the Lithuanian National Philharmonic Society with the Latvian National Symphony Orchestra. This concert was broadcast across Europe by Euroradio (EBU).

She has performed at venues such as Wigmore Hall, the Amsterdam Concertgebouw, Musikhuset Aarhus, the United Nations headquarters in Geneva, at the EMMA World Summit of Nobel Prize Peace Laureates in Warsaw and many others. Milda’s recent performances include a recital in the Laeiszhalle Recital Hall in Hamburg, at the Deal Music & Arts Festival, at the Petworth Festival, Biarritz Piano Festival and at the Palermo Classica Festival.

Milda won the Purcell School’s Concerto Competition which gave her the opportunity to perform Ravel’s Piano Concerto in G major at the Queen Elizabeth Hall in London. She also won First Prize in the international V. Krainev Piano Competition in Kharkov, Ukraine; the ‘Jury‘ Prize in the Pianale International Academy & Competition in Germany; and First Prize in the fourth International Piano Competition in Stockholm.

Franz Peter Schubert 31 January 1797 – 19 November 1828

Franz Schubert’s Piano Sonata in a minor op. post. 164, numbers among his early sonatas written between 1815 and 1819. In many of these pieces, Schubert still struggles with form; the Sonata in a minor from 1817 was a year in which Schubert showed a particular interest in the sonata, writing six piano sonatas, of which two are incomplete. The same year saw the composition of the violin and piano Duo Sonata, the B flat String Trio and some sixty songs. Written in March, the A minor Sonata is the first of the 18l7 sonatas in order of composition. however, is already wonderfully accomplished. In contrast to Schubert’s two later a-minor piano sonatas, the key here does not yet result in a tragic, fatalistic sound. This is also due to the fact that he took every opportunity to brighten the key to the major, or to swerve into neighbouring, friendlier harmonic regions.

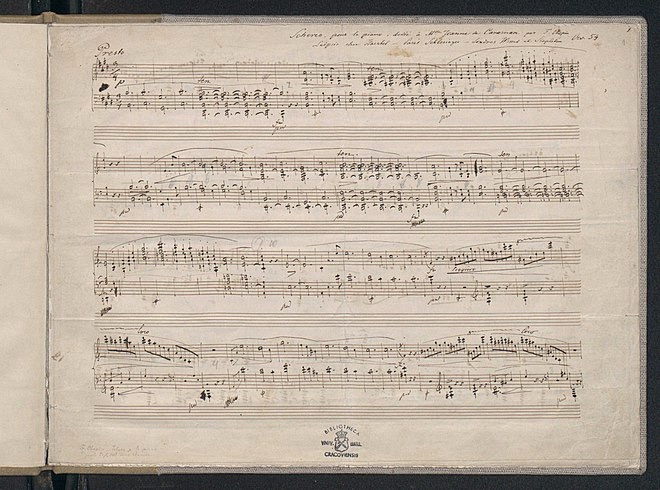

Autograph manuscript of Scherzo No. 4, Op. 54 in E major, 1842–1843, Biblioteka Jagiellonska, Kraków

The Scherzo No. 4, Op. 54, in E major was composed in 1842 in Nohant and was published in 1843. Unlike the preceding three scherzi (Op. 20, Op. 31, Op. 39) It is one of Chopin’s most elegiac works, and without doubt contains some of the most profound and introspective music the composer ever wrote

It is the only one of Chopin’s four scherzos primarily in a major key and as one critic explains, “When Chopin is at his happiest, most outwardly serene, then, for the pianist, he is at his most treacherous and its mercurial brilliance and whimsy are notoriously hard to control.” It was also a favourite of Saint – Saens

The four Scherzi of Chopin are single-movement pieces for solo piano, composed between 1833 and 1843. They are often linked to Chopin’s four ballades , composed in roughly the same period; these works are examples of large scale autonomous musical pieces, composed within the classical framework, but surpassing previous expressive and technical limitations. Unlike the classical model, the musical form adopted by Chopin is not characterised by humour or elements of surprise, but by highly charged “gestures of despair and demonic energy”.Commenting on the first scherzo, Schumann wrote: “How is ‘gravity’ to clothe itself if ‘jest’ goes about in dark veils?”

The highly programmatic themes depict the souls of Hell wailing in anguish

Après une lecture du Dante: Fantasia quasi Sonata (French for After a Reading of Dante: Fantasia quasi Sonata; also known as the Dante Sonata) is a one movement sonata written in 1849. It was first published in 1856 as part of the second volume of his Années de pèlerinage (Years of Pilgrimage).Originally a small piece entitled Fragment after Dante, consisting of two thematically related movements , which Liszt composed in the late 1830s and gave the first public performance in Vienna in November 1839.When he settled in Weimar in 1849, he revised the work along with others in the volume, and gave it its present title derived from Vitor Hugo’s Victor own work of the same name.

György Sándor Ligeti

28 May 1923 Transylvania Romania 12 June 2006

Vienna, Austria

The studies by Ligeti were written between 1985 and 2001. Ligeti originally intended to write twelve, in two books, on the model of Debussy’s piano études, but apparently he enjoyed writing them so much that he eventually wrote eighteen, in three books, and would have added more had illness not prevented him.They are indeed works of formidable difficulty, and a mere look at the printed page is enough to make the heart of the stoutest pianist quail. Although they do require the traditional virtuoso techniques involving speed, finger dexterity and strength, perhaps the greatest difficulties are of a different order: the two hands often play nearly independent lines with different rhythms and stresses. Ligeti’s writing exploits the whole range of the piano, including the very highest pitches, and the dynamic indications go from the extremely loud to the extremely quiet. He is also fond of the carrying a figure up to the extreme heights and then starting again in the depths, and of doing both simultaneously. He gave the individual études titles, in various languages, which indicate the character of the pieces. I should add that Ligeti, though he worked out the études at the piano, could not actually play them himself.From 1985 to 2001, Ligeti completed three books of Etudes for piano (Book I, 1985; Book II, 1988–94; Book III, 1995–2001). Comprising eighteen compositions in all, the Études draw from a diverse range of sources, including gamelan,African polyrhythms Béla Bartók, Conlon Nancarrow, Thelonious Monk and Bill Evans. Pour Irina is the 16th Study from the third book .