Amazing there is a piano genius is in our midst ……….Thomas Kelly a new Ogdon ………piano playing the like of which is a once in a lifetime experience .

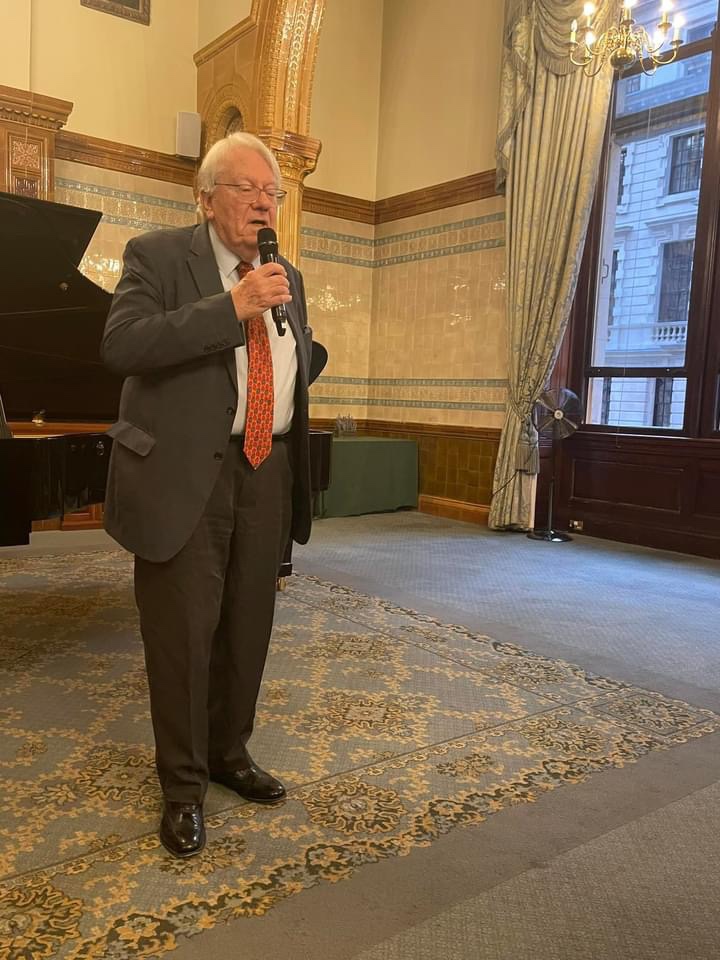

Rachmaninov’s first sonata was performed in the very room where the master gave his last London performance in 1939 ( you can read my review from a recent performance here .

Thomas Kelly at St James’s Piccadilly musicianship and mastery mark the return of a Golden Age but of the thinking virtuoso.

I know the Ogdon recording that was one of the first to appear commercially and I have heard another two remarkable Russian pianists play it recently .They all play with remarkable clarity and phenomenal technical mastery but there is a secret line in this work that is very hard to find.It can turn a problematic work – for Rachmaninov too – into a tone poem of extraordinary poetic potency.

It was Alexandre Kantorow who I heard recently who had found that elusive thread that weaves a maze of notes into a cauldron of potent sounds of great significance.A leit motif that appears throughout and is the thread to this up until now elusive work.Listening to Thomas Kelly recently I was overwhelmed by the importance of a work I had up until now always thought of as the poor brother of the Second Sonata.Thomas Kelly and Alexandre Kantorow had found the elusive thread that gave great cohesion and architectural shape to this early work.They also had a kaleidoscopic range of sounds and a phenomenal technical mastery.

I was amazed last night to watch Tom play with such assurance and mastery hardly moving but watching and listening with absolute authority .There was not a moment of doubt about where all the nuts and bolts should go and like Sokolov he would lean over to strike a bass note at exactly the moment of most impact emotionally and architecturally.I think the Sonata deserves to be in the Guinness book of records for the most notes in the shortest space of time and it was an amazing feat of piano playing of genius from this pianist still only in his early twenties.But there was much more besides as there was a sense of colour and balance and a range of sounds and touch that turned this magnificent Steinway Concert Grand into an orchestra of Philadelphian proportions.

But that was just an opener for the four Liszt Paganini studies of breathtaking virtuosity with the beguiling charm and colours of the masters of the Golden age of piano playing.Rachmaninov’s devilish transcription of the Mendelssohn Scherzo was thrown off with the same ease that Moiseiwitsch (also a member of the Liberal Club) managed to record by the skin of his teeth. Ravishing beauty of Rachmaninov’s own Lilacs was followed by the Mephisto Waltz played with devilish virtuosity and some extra notes added by Busoni and even later by Horowitz.I was surprised that I actually thought the original Liszt was superior to these slight alterations or additions that Busoni ( a pupil of Liszt) had made and the addition of Horowitz that rather spoils the ending with too much sound rather than Liszt’s rather terse single note of much greater effect.Liszt had after all changed the ending of his Sonata from a crowd pleasing triumphant ending to one of the most genial visionary pages in all the romantic piano repertoire.Busoni’s slight additions to La Campanella are quite teasingly and tastefully done whereas his triumphant ending to the Goldberg Variations I find hard to accept just as I found unnecessary in a masterpiece that is Liszt’s original version of the First Mephisto Waltz.

Scarlatti’s little Sonata in B minor was played with the jeux perlé of other times.Tom had by now entered another world and his Scarlatti had entered this world too and was for my taste a little too ear teasing and unlike the performance i had heard recently as an opening to his concert before the Rachmaninov rather than after .But what artistry and what a musician that can adapt and change like a chameleon to the atmosphere and perfumes of the moment.One expects De Pachmann to talk to the public to tell them how he is getting on or guide them through a performance pointing out moments that might be influenced by this or that colleague.But De Pachmann was an old man and much feted artist – Thomas Kelly still has fifty years to go before he reaches that status!

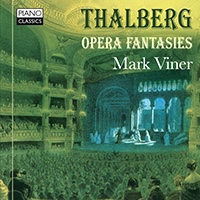

What extraodinary ravishing beauty he brought to the Thalberg Don Pasquale Fantasie A work wrapped up in piano trickery of such ingenious invention that in his day it made him a serious rival for Liszt the virtuoso.Liszt’s genius prevailed though and took him to a visionary world that opened up new vistas that were then taken up by Busoni and so into the next century.Tom’s mastery of style, colour and balance are a potent mixture that with his complete technical mastery can bring this world back to us with beguiling authority.Thomas Kelly – Piano Man !

Dr Hugh Mather comments:’Couldn’t agree more. We hear all the up-and-coming pianists at Perivale and I have no doubt that Thomas is in a league of his own. Simply phenomenal. Will be exciting to watch his progress over the next few years.’

David Earl ,the distinguished pianist comments :’This is phenomenal playing of a work I know well, and was inspired to learn thanks to the Ogdon RCA recording. Thomas’s layering of the 3rd movement’s paragraphs, and lyrical inner voicing is possibly the finest performance yet of Opus 28. Truly great. Thank you for posting Christopher.’

In 1939, Rachmaninoff gave his last ever UK recital in the David Lloyd George Room at the National Liberal Club, London. Now, in the very same room, 2021 Leeds finalist Thomas Kelly marks the 150th year since Rachmaninoff’s birth, and the 80th year since his death, with a programme of virtuoso repertoire celebrating Rachmaninoff alongside other legendary pianist-composers.

Rachmaninoff’s formidable Piano Sonata No.1 comprises the first half of his impressive programme, with Liszt and Thalberg highlighted in the second half, culminating with Horowitz’s transcription of Busoni’s arrangement of Liszt’s Mephisto Waltz No. 1 – an emblem of the rich history of virtuoso performers and their role in the creation and development of piano repertoire, fittingly delivered by one of the most exciting young virtuosos of today.

Programme:

Rachmaninoff Sonata No.1 in D Minor Op.28

INTERVAL

Liszt Paganini Etudes No.2, 3, 4, 6

Thalberg Grande fantasie sur des motifs de l’Opera “Don Pasquale” by Donizetti

Mendelssohn/Rachmaninoff Scherzo from “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”

Rachmaninoff Lilacs Op.21 No.5

Liszt/Busoni/Horowitz Mephisto Waltz No.1

Piano Sonata No. 1 in D minor op 28 was completed in 1908.It is the first of three “Dresden pieces”, along with the symphony n.2 and part of an opera, which were composed in the quiet city of Dresden.It was originally inspired by Goethe’s tragic play Faust,although Rachmaninoff abandoned the idea soon after beginning composition, traces of this influence can still be found.After numerous revisions and substantial cuts made at the advice of his colleagues, he completed it on April 11, 1908. Konstantin Igumnov gave the premiere in Moscow on October 17, 1908. It received a lukewarm response there, and remains one of the least performed of Rachmaninoff’s works.He wrote from Dresden, “We live here like hermits: we see nobody, we know nobody, and we go nowhere. I work a great deal,”but even without distraction he had considerable difficulty in composing his first piano sonata, especially concerning its form.Rachmaninoff enlisted the help of Nikita Morozov , one of his classmates from Anton Arensky’s class back in the Moscow Conservatory, to discuss how the sonata rondo form applied to his sprawling work.Rachmaninov performed in 1907 an early version of the sonata to contemporaries including Medtner.With their input, he shortened the original 45-minute-long piece to around 35 minutes and completed the work on April 11, 1908. Igumnov gave the premiere of the sonata on October 17, 1908, in Moscow,

Lukas Geniusas writes about his premiere recording of the Rachmaninov Sonata n. 1 to be issued in October : ‘About a year ago I came across a very rare manuscript of the Rachmaninov’s Sonata no.1 in its first, unabridged version. It had never been publicly performed.

This version of Sonata is not significantly longer (maybe 3 or 4 minutes, still to be checked upon performing), first movement’s form is modified and it is also substantially reworked in terms of textures and voicings, as well as there are few later-to-be-omitted episodes. The fact that this manuscript had to rest unattended for so many years is very perplexing to me. It’s original form is very appealing in it’s authentic full-blooded thickness, the truly Rachmaninovian long compositional breath. I find the very fact of it’s existence worth public attention, let alone it’s musical importance. Pianistic world knows and distinguishes the fact that there are two versions of his Piano Sonata no.2 but to a great mystery there had never been the same with Sonata no.1.’

The Mephisto Waltzes (German: Mephisto-Walzer) are four waltzes composed from 1859 to 1862, from 1880 to 1881, and in 1883 and 1885. Nos. 1 and 2 were composed for orchestra, and later arranged for piano, piano duet and two pianos, whereas nos. 3 and 4 were written for piano only. Of the four, the first is the most popular and has been frequently performed in concert and recorded.

The first Mephisto Waltz is a typical example of programme music taking for its program an episode from Nikolaus Lenau’s 1836 verse drama Faust not Goethe. The following program note, which Liszt took from Lenau, appears in the printed score:

There is a wedding feast in progress in the village inn, with music, dancing, carousing. Mephistopheles and Faust pass by, and Mephistopheles induces Faust to enter and take part in the festivities. Mephistopheles snatches the fiddle from the hands of a lethargic fiddler and draws from it indescribably seductive and intoxicating strains. The amorous Faust whirls about with a full-blooded village beauty in a wild dance; they waltz in mad abandon out of the room, into the open, away into the woods. The sounds of the fiddle grow softer and softer, and the nightingale warbles his love-laden song.

In 1843 Thalberg had married in Paris the daughter of the famous bass Luigi Lablache, widow of the painter Boucher. Attempts at operatic composition proved unsuccessful, with Florinda, staged in London in 1851 and Cristina di Suezia in Vienna four years later. His career as a virtuoso continued until 1863, when he retired to Posilippo, near Naples, to occupy himself for his remaining years with his vineyards. He died in Posilippo in 1871.

Some mystery surrounds the birth and parentage of the virtuoso pianist Sigismond Thalberg, popularly supposed to have been the illegitimate son of Count Moritz Dietrichstein and the Baroness von Wetzlar, born at Pâquis near Geneva in 1812. His birth certificate, however, provides him with different and relatively legitimate parentage, the son of a citizen of Frankfurt, Joseph Thalberg. There seems no particular reason, therefore, to suppose the name Thalberg an invention. Legend, however, provides the story of the Baroness proclaiming him a valley (“Thal”) that would one day rise to the heights of a mountain (“Berg”). Thalberg’s schooling took him to Vienna, where his fellow-pupil the Duke of Reichstadt, the son of Napoleon, almost persuaded him to a military career. Musical interests triumphed and he was able to study with Simon Sechler and with Mozart’s pupil Hummel. In Vienna he performed at private parties, making a particular impression when, as a fourteen-year-old, he played at the house of Prince Metternich. By 1828 he had started the series to compositions that were to prove important and necessary to his career as a virtuoso. In 1830 he undertook his first concert tour abroad, to England, where he had lessons from Moscheles. In 1834 he was appointed Kammervirtuos to the Emperor in Vienna and the following year appeared in Paris, where he had lessons from Kalkbrenner and Pixis.

Paris in the 1830s was a city of pianists. The Conservatoire was full of them, while salons and the showrooms of the chief piano-manufacturers Erard and Pleyel resounded with the virtuosity of Kalkbrenner, Pixis, Herz, and, of course, Liszt. The rivalry between Thalberg and Liszt was largely fomented by the press. Berlioz became the champion of the latter, while Fétis trumpeted the achievements of Thalberg. Liszt, at the time of Thalberg’s arrival in Paris, was in Switzerland, where he had retired with his mistress, the Comtesse Marie d’Agoult. It was she who wrote, under Liszt’s name, a disparaging attack on Thalberg, to which Fétis replied in equally offensive terms. The so-called “revolutionary princess”, Princess Belgiojoso, achieved a remarkable social coup when she persuaded the two virtuosi to play at her salon, in a concert in aid of Italian refugees. As in other such contests victory was tactfully shared between the two. Thalberg played his Moses fantasy, and Liszt answered with his new paraphrase from Pacini’s opera Niobe. The Princess declared Thalberg the first pianist in the world, while Liszt was unique. She went on to commission a series of variations on a patriotic theme from Bellini’s I Puritani from the six leading pianists in Paris, to which Liszt, Thalberg, Chopin, Pixis, Herz and Czerny contributed. This composite work, Hexaméron, remained in Liszt’s concert repertoire.The first of these operas was written in the winter of 1842 and performed early in January the following year in Paris. The elderly Don Pasquale attempts late marriage, with the purpose of siring children and thus disinheriting his nephew Ernesto. He is induced to see reason by what he supposes to be a real marriage to his nephew’s betrothed, disguised and behaving as an untamed shrew. All ends happily, when Don Pasquale agrees, with relief, to allow his nephew to marry the girl. Thalberg’s fantasy captures something of the spirit, humour and romance of its source

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2015/12/29/thalberg-goes-to-the-opera-with-mark-viner/

Mark Viner another great English virtuoso dedicated to bringing a forgotten world back to life with mastery and artistry .A swashbuckling extravaganza of nineteenth century pianism and a veritable contribution to Romantic Revivalism. This, Mark Viner’s début recording, presents the operatic paraphrases of the neglected pianist‐composer Sigismond Thalberg, aristocratic rival of Liszt and innovator of the so‐called ‘three‐hand effect’. Here are some of the very finest of his works – a music of opulent grandeur which draws upon all the heady romantic rhetoric and dramatic narrative of the opera house whilst being sumptuously conceived for the piano. A tour de force of virtuosity and an evocation of an era. Mark Viner is one of the most exciting young British pianists of his generation. 1st prize winner of the 2012 Alkan‐Zimmerman Competition in Athens, he is also the Chairman of the Alkan Society and is steadily gaining a reputation for his bold championing of unfamiliar pianistic terrain.

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2020/01/04/a-la-recherche-de-thalberg/

Lilacs (Siren) was composed by Rachmaninov in April 1902, along with ten other songs that were then combined with an earlier piece, Fate (1900), into the opus 21 set of 12 Songs published by Guthiel in December 1902. Rachmaninov was married to Nathalie Satin in April 1902 and wrote this set largely to help pay for their honeymoon, which lasted until August. In June,he wrote to his friend Nikita Morozov, “these songs were written in a hurry and are quite unfinished and unbeautiful. But they’ll almost have to stay this way, as I don’t have time to tinker with them further. It would be nice to get done with all this dirty work by the July 1st so I can get to work on something new.”

In the morning, at daybreak,

over the dewy grass,

I will go to breathe the crisp dawn;

and in the fragrant shade,

where the lilac crowds,

I will go to seek my happiness...

In life, only one happiness

it was fated for me to discover,

and that happiness lives in the lilacs;

in the green boughs,

in the fragrant bunches,

my poor happiness blossoms...

The poem is by Ekatrina Beketova , an eighteenth-century Russian poet; it describes bunches of lilac flowers as “where happiness lives.”

Around 1908, Rachmaninov began to receive bouquets of lilacs at his performances from an anonymous admirer at every concert or recital Rachmaninov gave, no matter where he was appearing in the world, through 1918.Madame Felka Rousseau of Russia identified herself to Rachmaninov as the mysterious donor of the lilacs. She stated that she would’ve preferred to have remained anonymous, but was curious as to why so much time had gone by since he had appeared in Russia.He explained that as long as the current political situation remained as it was in Russia, it was unlikely that he would be able to return at all. Soon after that, the lilacs stopped coming.

Lilacs was one of only two of Rachmaninov’s own songs that he adapted into solo piano transcriptions. He made the arrangement around 1913 and often used it as an encore piece. He recorded it three times, the first such recordings being made for Victor in 1920, the second as an Ampico piano roll sometime in the 1920s, and the last time at his final recording session held at the RCA studio in Hollywood on February 6, 1942. This last version would not be released until long after Rachmaninov’s death.

Thomas Kelly was born in November 1998. He started playing the piano aged 3, and in 2006 became Kent Junior Pianist of the Year and attained ABRSM Grade 8 with Distinction. Aged 9, Thomas performed Mozart Concerto No. 24 in the Marlowe Theatre with the Kent Concert Orchestra. After moving to Cheshire, he regularly played in festivals, winning prizes including in the Birmingham Music Festival, 3rd prize in Young Pianist of The North 2012, and 1st prize in WACIDOM 2014. Between 2015 and 2021 Thomas studied with Andrew Ball, firstly at the Purcell School of Music and then at the Royal College of Music. Thomas has also gained inspiration from lessons and masterclasses with musicians such as Vanessa Latarche, William Fong, Ian Jones, Tatiana Sarkissova, Valentina Berman, Boris Berman, Paul Lewis, Mikhail Voskresensky and Dina Yoffe. Thomas began studying with Dmitri Alexeev in April 2021, with whom he will continue whilst studying Masters at the RCM.Thomas has won 1st prizes including Pianale International Piano Competition 2017, Kharkiv Assemblies 2018, at Lucca Virtuoso e Bel Canto festival 2018, RCM Joan Chissell Schumann competition 2019, Kendall Taylor Beethoven competition 2019, BPSE Intercollegiate Beethoven competition 2019 and the 4th Theodor Leschetizky competition 2020. In 2021 Thomas was a finalist in the Leeds International Piano Competition. Most recently, he was awarded 2nd prize and special prize for best semi-final performance at Hastings International Concerto Competition 2022.He has performed in a variety of venues, including the Wigmore Hall, the Cadogan Hall, St John’s Smith Square, Steinway Hall London, Holy Trinity Sloane Square, St James’ Piccadilly, Oxford Town Hall, St Mary’s Perivale, St Paul’s Bedford, the embassies of Russia and Brazil in London, the Poole Lighthouse Arts Centre, the Stoller Hall, Leeds Town Hall, at the North Norfolk Music Festival, Paris Conservatoire, the StreingreaberHaus in Bayreuth and separately at the Teatro Del Sale and the British Institute in Florence.Thomas is supported by the Kendall-Taylor award. He has been generously supported by the Keyboard Charitable Trust since 2020, and Talent Unlimited since 2021.

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2023/09/13/gabriele-sutkute-takes-mayfair-by-storm-passion-and-power-with-impeccable-style/

Thomas Kelly takes Florence by storm Music al British

Thomas Kelly at St Mary’s a programme fit for a Prince

Thomas Kelly at St Mary’s Masterly playing from the Golden Age

Thomas Kelly plays Beethoven 4 at the RCM cat and mouse with Sakari Oramo

Thomas Kelly at the Royal College of Music A star shining brightly