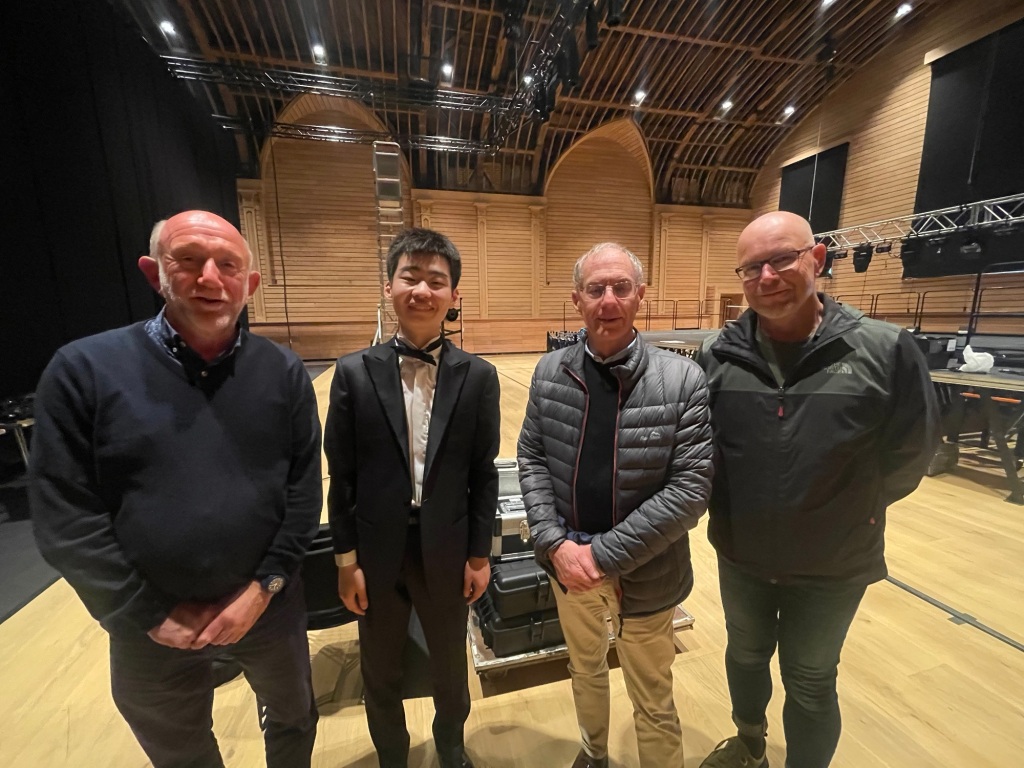

Hastings International Piano Competition Winner 2022

Bach French suite No. 6 in E minor BWV 817

Schubert Klavierstücke D. 946 no.2 E flat major

Chopin Barcarolle Op. 60

Schumann Davidsbündlertänze Op.6

In 2022, aged just 17, Japanese pianist Shunta Morimoto was unanimously awarded First Prize in the Hastings International Piano Concerto Competition following his performance of Schumann’s Piano Concerto. Here he ends his lunchtime recital with the same composer’s Davidsbündlertänze, a kaleidoscopically varied set of 18 ‘dances’ for Florestan and Eusebius – two supposed members of Schumann’s imaginary ‘League of David’, but actually representing twin aspects of his artistic personality.

In Association with Hastings International Piano Competition

I have heard Shunta many times over the past few years but rarely have I heard him play with the intimacy that only a large hall can afford .

Bach’s 6th French Suite was played with exquisite ornaments that shone like jewels and discreet changes of register that he acknowledged with sudden changes of colour of whispered tones just shadowing what it mirrored.A sense of dance that was hypnotic and tantalising in it’s subtlety. Bach is Song and Dance and nowhere more than in Shunta’s inspired hands.Each of the eight movements flowed so naturally that time stood still as the magnificence of Bach was revealed with simplicity and sublime beauty.

The second of the three Klavierstucke flowed from his fingers with a luminosity and fluidity that when the sinister undertones of the first episode suddenly appeared on the scene we were held in a spell of discovery not knowing how such a drama would play out. The storm in a teacup was followed by a second episode of refined beauty and sumptuous golden sounds.The whispered return of the opening melody was overwhelming in its impact as we were drawn into this intimate private world that this young man shared with us today.

Chopin’s Barcarolle was a continuous outpouring of song played by Shunta today with a simplicity and freedom that was hypnotic.From the opening deep C sharp he held us in a spell of aristocratic simplicity where the music was allowed to pour from his fingers as the waves washed around Chopin’s imaginary lagoon.The transition from the sublime beauty of the central episode to the final outpouring of nobility and heart rending passion was masterly controlled as we were held on a wave of sound that gradually increased in intensity until bursting point and the final disintegration.We could literally see the strands gradually unfolding until they wafted on high with a cadenza of breathtaking beauty where time seem to stand still as the notes unfolded with that inevitable simplicity that I have only ever experienced with Rubinstein in the hall next door.

Schumann’s Davidsbundlertanze filled the second half of this lunchtime recital where the freedom and subtle colours that Shunta found was nothing short of miraculous.There was passion and transcendental playing of astonishing natural ease where technical difficulties ceased to exist with an artist where music was burning within his being and was the only consideration.The beautiful fourteenth dance was played with glowing beauty and a balance that showed us too the very roots from which this sublime music had grown.The penultimate dance that Schumann describes as ‘from a distance’ was played with trance like beauty of etherial sounds that gradually built up to the final climax that dissolved as fast as it arrived.It left just the final dance that was played with subtle whispered sounds where we were caught in a spell of magic that was greeted by the silence of an audience unified in one of those rare magic moments that can still occasionally happen in the concert hall.

The spell was broken by an ovation that brought this young man back on stage for three encores .Chopin’s Study op 10 n. 4 was breathtaking not only for its transcendental virtuosity but more for the music he made of these notes .I have only ever heard from Perlemuter streams of sound and moving harmonies as one phrase was passed from the right hand to the left in a playful duet until the final outburst of passionate abandon.I have heard many pianists play this study but no one has ever played it with the musical mastery of this young man.

Bach’s prelude and fugue n.13 from the first book was Shunta’s way of thanking us and wanting to share with us again the sublime beauty of the Genius of Bach.

1748 portrait of Bach, showing him holding a copy of the six-part canon BWV 1076

21 March 1685 Eisenach 28 July 1750 (aged 65) Leipzig

The French Suites, BWV 812–817, are six suites which Johann Sebastian Bach wrote for the clavier (harpsichord or clavichord )between the years of 1722 and 1725.Although Suites Nos. 1 to 4 are typically dated to 1722, it is possible that the first was written somewhat earlier.The suites were later given the name ‘French’ (first recorded usage by F.W Marburg in 1762). Likewise, the English Suites received a later appellation. The name was popularised by Bach’s biographer Forkel , who wrote in his 1802 biography of Bach, “One usually calls them French Suites because they are written in the French manner.”This claim, however, is inaccurate: like Bach’s other suites, they follow a largely Italian convention.There is no surviving definitive manuscript of these suites, and ornamentation varies both in type and in degree across manuscripts.

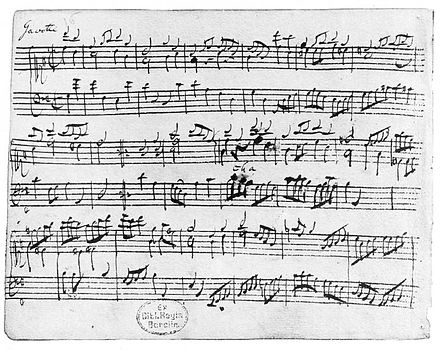

Suite No. 6 in E major, BWV 817

- Allemande

- Courante

- Sarabande

- Gavotte

- Polonaise

- Bourrée

- Menuet

- Gigue

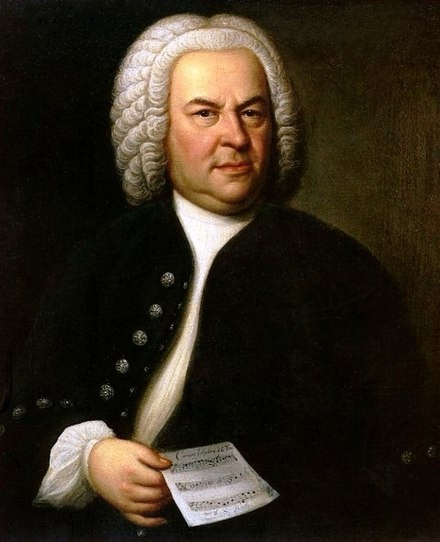

Franz Peter Schubert 31 January 1797 – 19 November 1828

The three “piano pieces” D.946, were completed in May 1828, the year Schubert died, and follow the far more well-known and popular Impromptus D.899 and D.935, which Schubert composed the previous year. Like the Impromptus, the Drei Klavierstücke express in microcosm so much of Schubert’s unique soundworld and musical personality – daring and unusual harmonies, beautiful songful melodies, and episodes of profound poignancy or intimacy. Throughout these three pieces, we hear the extraordinarily broad scope of his creativity and emotional landscape.

“He has sounds to express the most delicate feelings, of thoughts, indeed even for the events and conditions of human life.” – Robert Schumann

Untitled and unpublished in Schubert’s lifetime, it was Johannes Brahms who anonymously edited and published the Drei Klavierstücke in 1868 and gave the works their collective title. The second of the triptych is a five-part rondo. It opens in E-flat major, which connects it to the previous piece, though it is not known whether Schubert conceived the three pieces to be linked. An elegant barcarolle, the A section has an aria-like melody coloured by harmonic shifts between major and minor.

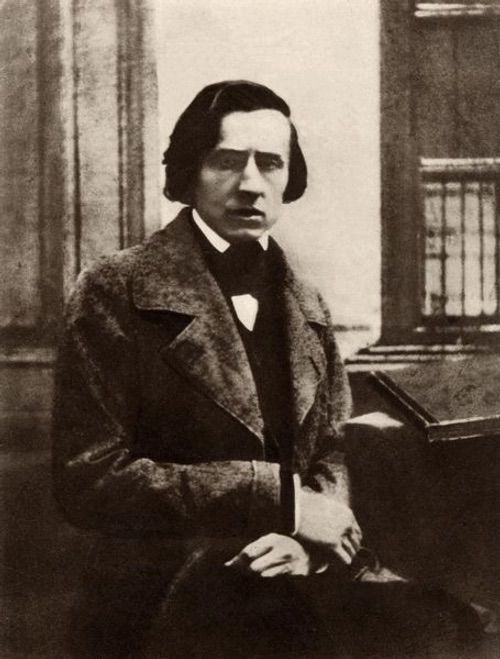

Daguerreotype, c. 1849

Frédéric François Chopin born Fryderyk Franciszek Chopin;

1 March 1810 – 17 October 1849

The Barcarolle in F sharp major op 60 , by Chopin was composed between autumn of 1845 and summer 1846, three years before his death. This is one of Chopin’s last major compositions, along with his Polonaise – Fantasie op 61. In the final years of his short life, Chopin reached a new plateau of creative achievement. His sketches from these years suggest that the agony of composition, the resistance it set up, wrested from him only music of an exceptional, transcendent quality. And nowhere is this clearer than in the three great extended works of 1845–6: the Barcarolle Op 60, Polonaise-Fantasie Op 61 and Cello Sonata Op 65

In the summer of 1845, alongside new mazurkas and songs, the Barcarolle was written . Perhaps by coincidence, perhaps by design, the last of the three Mazurkas, Op. 59, composed in the key of F sharp minor, ends with a switch to the bright F sharp major. And it is in that same F sharp major – a rare key in Chopin – that the Barcarolle begins. It is also in shades of F sharp major (as the work’s main key) that the Barcarolle’s musical narrative proceeds, departing from it and returning to it again.

We do not know when and in what circumstances the idea for this music was conceived. Chopin never visited Venice. He had but a fleeting encounter with Italian landscapes and atmosphere on a boat trip from Marseilles to Genoa. A storm at sea was perhaps more likely to have impressed itself onto his memory of that fatiguing expedition than any image of the city. It is assumed that Chopin could have been given the idea of composing a barcarolle, as well as a prototype for its shape and character, by works in that genre which functioned in the current musical repertoire, especially in opera, and above all in Rossini and Auber. All the operatic barcarolles by those composers were well known to Chopin. He could not possibly have forgotten the barcarolles from Guilllaume Tell, La muette de Portici or Fra Diavolo.

The barcarolle genre was becoming increasingly popular in vocal and pianistic lyricism. We know that Chopin gave his pupils Mendelssohn’s Lieder ohne Worten to play. The sixth number in the first book of the Songs without Words bears the title ‘Venezianisches Gondellied’ Venetian boat song. This could certainly have been a path for Chopin into the convention of the nineteenth-century barcarolle. Yet in Chopin’s Barcarolle there are no references to either the historical tradition of the songs of the Venetian gondoliers (as do appear in Liszt’s ‘Venezia e Napoli’) or the banal idiom of the opera-salon barcarolle of the day, which would soon reach its pinnacle with the Barcarolle from Offenbach’s Les contes d’Hoffmann. In Chopin’s Barcarolle, beneath the cloak of the generic convention, we find music that encapsulates his supreme pianistic experience and the musical maturity that he had attained during this rather reflective phase, and at the same time music that echoes his experience of the whole Mediterranean south of Europe: the Italian songs of Lina Freppa, Bellini’s bel canto, the passionate Spanish songs of Pauline Viardot, which Chopin listened to in rapture, and the wild, but incredibly beautiful landscape of Majorca.

One peculiar, extraordinary moment comes at the point which Chopin defines with the words dolce sfogato and precedes with a lead-in filled with hushed mystery. That enigmatic, unfathomed dolce sfogato then starts to develop and bloom.

In his Notes on Chopin, André Gide went into raptures: ‘Sfogato, he wrote; has any other musician ever used this word, would he have ever had the desire, the need, to indicate the airing, the breath of breeze, which, interrupting the rhythm, contrary to all hope, comes freshening and perfuming the middle of his barcarolle?’

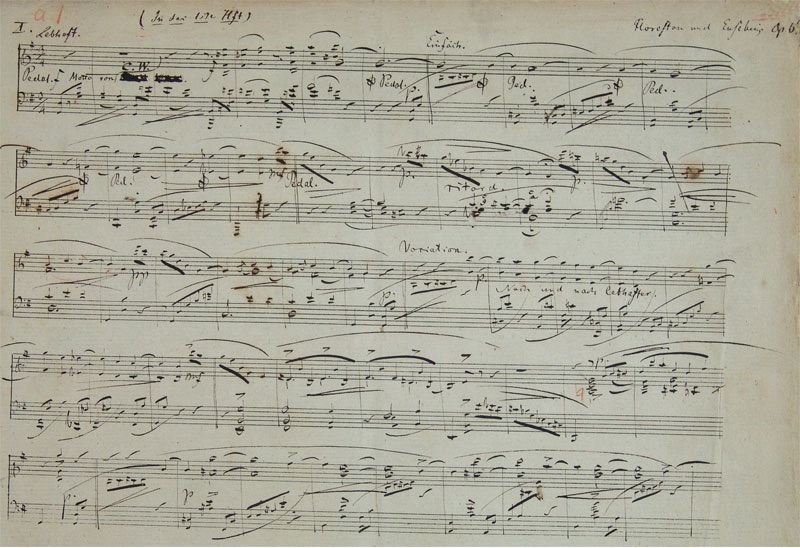

Robert Schumann Davidsbündlertänze (Dances of the League of David), op 6, is a group of eighteen pieces composed in 1837 by Robert Schumann , who named them after his music society Davidsbundler. The low opus number is misleading: the work was written after Carnaval op 9 and the Symphonic Studies op.13.

Original manuscript first page

Robert Schumann’s early piano works were substantially influenced by his relationship with Clara Wieck . On September 5, 1839, Schumann wrote to his former professor: “She was practically my sole motivation for writing the Davidsbündlertänze, the Concerto , the Sonata and the Novelettes .” They are an expression of his passionate love, anxieties, longings, visions, dreams and fantasies.

Clara’s Mazurka printed in the 1997 urtext edition of Davidsbundler

The theme of the Davidsbündlertänze is based on a mazurka by Clara Wieck.The intimate character pieces are his most personal work and in 1838, Schumann told Clara that the Dances contained “many wedding thoughts” and that “the story is an entire Polterabend (German wedding eve party, during which old crockery is smashed to bring good luck)”.

The pieces are not true dances but characteristic pieces, musical dialogues about contemporary music between Schumann’s characters Florestan and Eusebius. These respectively represent the impetuous and the lyrical, poetic sides of Schumann’s nature. Each piece is ascribed to one or both of them. Their names follow the first piece and the appropriate initial or initials follow each of the others except the sixteenth (which leads directly into the seventeenth, the ascription for which applies to both) and the ninth and eighteenth, which are respectively preceded by the following remarks: “Here Florestan made an end, and his lips quivered painfully”, and “Quite superfluously Eusebius remarked as follows: but all the time great bliss spoke from his eyes.” The suite ends with the striking of twelve low Cs to signify the coming of midnight.

The first edition is prefaced by :

Old saying

In each and every age

joy and sorrow are mingled:

Remain pious in joy,

and be ready for sorrow with courage

The movements are :

- Lebhaft: Lively (Vivace),Florestan and Eusebius;

- Innig: Intimately (Con intimo sentimento), , Eusebius;

- Etwas hahnbüchen: Somewhat clumsily (Un poco impetuoso) (1st edition), Mit Humor: With humor (Con umore) (2nd edition), Florestan (hahnbüchen, translates as “cockeyed” )

- Ungeduldig: Impatiently (Con impazienza), , Florestan;

- Einfach: Simply (Semplice), , Eusebius;

- Sehr rasch und in sich hinein: Very quickly and inwardly (Molto vivo, con intimo fervore) (1st edition), Sehr rasch: Very quickly(Molto vivo) (2nd edition), , Florestan;

- Nicht schnell mit äußerst starker Empfindung: Not fast, with very great feeling (Non presto profondamente espressivo) (1st edition), Nicht schnell: Not fast (Non presto) (2nd edition), Eusebius;

- Frisch: Freshly (Con freschezza), Florestan;

- No tempo indication (metronome mark of ♩ = 126) (1st edition), Lebhaft: Lively (Vivace) (2nd edition), , Florestan;

- Balladenmäßig sehr rasch: Balladically very fast (Alla ballata molto vivo) (1st edition), (“Sehr” and “Molto” capitalized in 2nd edition), (ends major), Florestan;

- Einfach: Simply (Semplice), Eusebius;

- Mit Humor: With humor (Con umore), Florestan;

- Wild und lustig: Wildly and merrily (Selvaggio e gaio), Florestan and Eusebius;

- Zart und singend: Tenderly and singing (Dolce e cantando), Eusebius;

- Frisch: Freshly (Con freschezza), – Etwas bewegter: With agitation (poco piu mosso),with a return to the opening section (with the option to go round the piece once more), Florestan and Eusebius;

- Mit gutem Humor: With good humor (Con buon umore) (in 2nd edition, “Con umore”), – Etwas langsamer: A little slower (Un poco più lento); leading without a break into

- Wie aus der Ferne: As if from afar (Come da lontano), (including a full reprise of No. 2), Florestan and Eusebius; and finally,

- Nicht schnell: Not fast (Non presto), Eusebius.

Shunta Morimoto takes Hastings by Storm