Some more superb playing from Shunta Morimoto in his annual recital in the Villa Aldobrandini in Frascati.

A fascinating programme opening with one of Bach’s finest of seven toccatas – the one in F sharp minor followed by one of Chopin’s most perfect works the Barcarolle op 60 in F sharp major. The first encore too was in F sharp major with the Fugue from Book 1 of the ‘Wohltemperierte Klavier’.Two works by Schubert followed with his C minor Sonata prefaced by the E flat Klavierstucke .I would not be surprised if all these key relationships were not just a coincidence but designed to give an architectural shape to the entire programme.Shunta at only nineteen has recently won two major competitions since his last appearance in this series organised by the distinguished French pianist Marylene Mouquet .It is not only his superb technical mastery but also his intelligent musicianship that shines through all he does.

Playing with a total commitment where the sounds he is making in the moments of creation are his life’s blood as he is able to hold the audience in his spell where we too feel that we are on a voyage of discovery with him.I have heard Shunta recently play the Schubert C minor Sonata but today’s performance had a drive and urgency that was mesmerising.Moments of sublime beauty too but always with the burning intensity of the most dramatic of the composers last works.

The Schubert Sonata I have written about recently but today was an even greater surprise as this burning intensity shone new light on so many memorable moments.

Here he is playing the Sonata as top prize winner of a competition https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2024/03/03/shunta-morimoto-takes-hastings-by-storm/

The most extraordinary moment was in the development of the first movement where the streams of chromatic scales were played so quietly to allow the menace of the left hand to be fully appreciated .The rests gave the opening rhythm a terrifying significance before bursting out into the open once more.What noble beauty there was to the Adagio too building into a dynamic force that made the disarmingly beautiful last bars an oasis of whispered beauty . The legato lines of the ‘Menuetto’ where bar lines ceased to exist I have never heard played so beautifully .The gently innocuous last movement just bubbled over with pastoral simplicity but also showing us how much more there was of Beethoven’s tempestuous character in this work than in his others.

What a genial surprise to hear the Allegretto from the Klavierstucke as a bridge between the Barcarolle and the Sonata.The disarming simplicity of the melodic line was only disturbed by the momentary ruffling of the waters returning to the sublime beauty of a work we only ever hear with it’s other two neighbours ,which never really allows us to fully appreciate this unique tone poem on its own terms .Shunta played it,like all he touches,with refined good taste and beauty before the eruption of Schubert in tempestuous C minor mood.

Chopin’s Barcarolle too ,one of Chopin’s most mellifluous works that from the opening deep bass C sharp is a continuous outpouring of song .But today Shunta was in a turbulent mood and he brought an unusual intensity and drive to the work that gave it nobility and poignancy.The gently rocking rhythm to the central section was played truly ‘sotto voce’ as the composer indicates, leading into the most sublime ‘dolce sfogato’ that today in Shunta’s hands came like a ray of golden sunlight suddenly shining down on the water.The passion he then brought to the final pages was breathtaking in it’s abandon and sumptuous rich sound.The final gasping ‘calando’ phrases were played with the subtle inflections that only the greatest of bel canto singers could express .The streams of barely whispered notes with the left hand tenor melody allowed to emerge created a magic that was only to be dispelled with the final mighty fortissimo chords.All through this work there had been a sense of legato and weight where every strand was allowed to sing with beauty and intensity.Shunta’s hands were like limpets on the keys extracting every ounce of meaning from Chopin’s simple rocking melodic line.

The opening Bach Toccata too had been of burning intensity but also of great clarity with the deep bass notes acting as an anchor to the streams of the opening flourishes.The religious calm he brought to the ‘Adagio’ was played with simplicity and very little pedal that gave it a disarming purity before the spiky ‘Presto e staccato’. Shunta’s complete understanding of the contrapuntal direction of the voices showed his remarkable musicianship as he was able to carve this knotty into an architectural shape that took us to recitativi and the final relentless drive on to the noble finish.

Shunta was obviously in Fugal mood today as his first encore was the Fugue in F sharp from Book 1 of the Well Tempered Clavier.A clarity and again an unusual choice to play just the fugue divorced from its prelude.It had me thinking,in my ignorance,that maybe this was a piece by Rameau such was the rhythmic clarity and Sokolovian precision of articulation.Of course a great artist always has a surprise of two in store and Shunta certainly did today.Chopin’s study op 10 n.4 was played with a velocity and ease that were truly breathtaking.It was allied to a sense of character that made the final page as exciting as I remember from Rubinstein when he would raise himself up from the piano tool as he ignited the final page even in his 90th year!

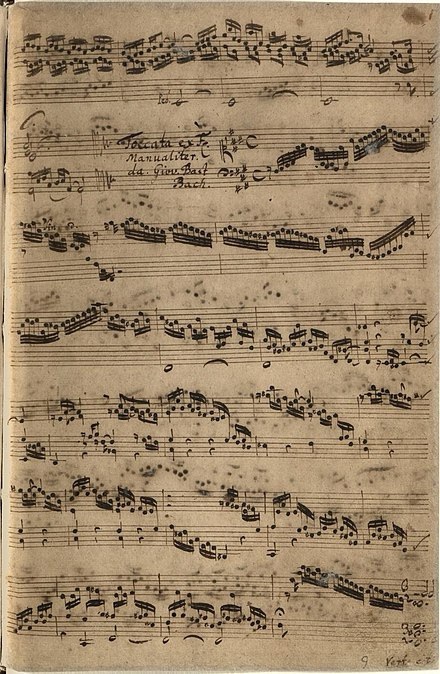

The Toccatas for Keyboard, BWV 910–916, are seven pieces for clavier written by J S Bach Although the pieces were not originally organized into a collection by Bach himself (as were most of his other keyboard works, such as the Well Tempered Clavier and the English Suites etc.), the pieces share many similarities, and are frequently grouped and performed together under a collective title.

The beginning of the BWV 910 F# minor Toccata – from the Andreas Bach Book, in the hand of Johann Christoph Bach.

The seven Toccatas by J.S. Bach contain some of the great master’s most joyous keyboard music. They are youthful, improvisatory, virtuoso works, composed in the aftermath of Bach’s trip in 1705 to Lübeck to hear the great organist and composer Buxtehude.They represent Bach’s earliest keyboard compositions known under a collective title.The earliest sources of the BWV 910, 911 and 916 toccatas appear in the Andreas Bach Book ,an important collection of keyboard and organ manuscripts of various composers compiled by Bach’s oldest brother, Johann Christoph between 1707 and 1713. An early version of the BWV 912 (known as the BWV 912a) also exists in another collection compiled by Johann Christoph Bach known as the ‘Moller manuscript’ from around 1703 to 1707.This indicates that most of these works originated no later than Bach’s early Weimar years, though the early northern German style indicates possible Arnstadt origin.Though the specific instrumentation is not given for any of the works, none of them call for pedal parts and like Bach’s other clavier works, these toccatas are frequently performed on the piano

- Toccata in F-sharp minor, BWV 910

- (Toccata)

- [no tempo indication]

- Presto e Staccato (Fuga)

- [no tempo indication]

- (Fuga)

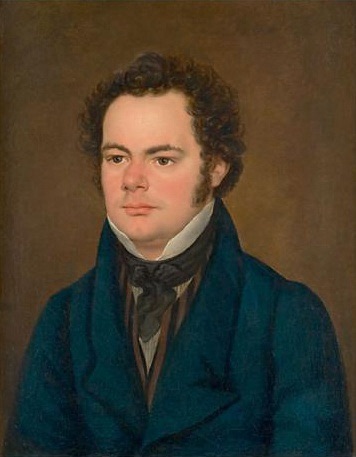

Schubert’s last three piano sonatas ,D.958, 959 and 960, are his last major compositions for solo piano. They were written during the last months of his life, between the spring and autumn of 1828, but were not published until about ten years after his death, in 1838–39.Like the rest of Schubert’s piano sonatas, they were mostly neglected in the 19th century but by the late 20th century, however, public and critical opinion had changed, and these sonatas are now considered among the most important of the composer’s mature masterpieces.

Franz Peter Schubert 31 January 1797 – 19 November 1828

The last year of Schubert’s life was marked by growing public acclaim for the composer’s works, but also by the gradual deterioration of his health. On March 26, 1828, together with other musicians in Vienna he gave a public concert of his own works, which was a great success and earned him a considerable profit. In addition, two new German publishers took an interest in his works, leading to a short period of financial well-being. However, by the time the summer months arrived, Schubert was again short of money and had to cancel some journeys he had previously planned.

Schubert had been struggling with syphilis since 1822–23, and suffered from weakness, headaches and dizziness. However, he seems to have led a relatively normal life until September 1828, when new symptoms appeared. At this stage he moved from the Vienna home of his friend Franz von Schober to his brother Ferdinand’s house in the suburbs, following the advice of his doctor; unfortunately, this may have actually worsened his condition. However, up until the last weeks of his life in November 1828, he continued to compose an extraordinary amount of music, including such masterpieces as the three last sonatas.

Schubert probably began sketching the sonatas sometime around the spring months of 1828; the final versions were written in September. The final sonata was completed on September 26, and two days later, Schubert played from the sonata trilogy at an evening gathering in Vienna.In a letter to Probst (one of his publishers), dated October 2, 1828, Schubert mentioned the sonatas amongst other works he had recently completed and wished to publish.However, Probst was not interested in the sonatas,and by November 19, Schubert was dead.In the following year, Schubert’s brother Ferdinand sold the sonatas’ autographs to another publisher, Anton Diabelli, who would only publish them about ten years later, in 1838 or 1839.Schubert had intended the sonatas to be dedicated to Hummel , whom he greatly admired. Hummel was a leading pianist, a pupil of Mozart , and a pioneering composer of the Romantic style (like Schubert himself).However, by the time the sonatas were published in 1839, Hummel was dead, and Diabelli, the new publisher, decided to dedicate them instead to composer Robert Schumann , who had praised many of Schubert’s works in his critical writings.

Sonata in C minor, D. 958

Allegro ;Adagio;Menuetto:Allegro – Trio ;Allegro

Franz Schubert

The three “piano pieces” D.946, were completed in May 1828, the year Schubert died, and follow the far more well-known and popular Impromptus D.899 and D.935, which Schubert composed the previous year. Like the Impromptus, the Drei Klavierstücke express in microcosm so much of Schubert’s unique soundworld and musical personality – daring and unusual harmonies, beautiful songful melodies, and episodes of profound poignancy or intimacy. Throughout these three pieces, we hear the extraordinarily broad scope of his creativity and emotional landscape.

“He has sounds to express the most delicate feelings, of thoughts, indeed even for the events and conditions of human life.” – Robert Schumann

Untitled and unpublished in Schubert’s lifetime, it was Johannes Brahms who anonymously edited and published the Drei Klavierstücke in 1868 and gave the works their collective title. The second of the triptych is a five-part rondo. It opens in E-flat major, which connects it to the previous piece, though it is not known whether Schubert conceived the three pieces to be linked. An elegant barcarolle, the A section has an aria-like melody coloured by harmonic shifts between major and minor.

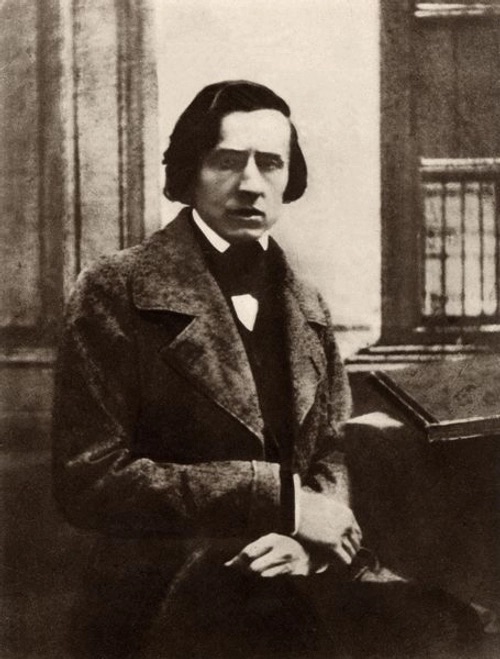

Frédéric François Chopin born Fryderyk Franciszek Chopin;

1 March 1810 – 17 October 1849

The Barcarolle in F sharp major op 60 , by Chopin was composed between autumn of 1845 and summer 1846, three years before his death. This is one of Chopin’s last major compositions, along with his Polonaise – Fantasie op 61. In the final years of his short life, Chopin reached a new plateau of creative achievement. His sketches from these years suggest that the agony of composition, the resistance it set up, wrested from him only music of an exceptional, transcendent quality. And nowhere is this clearer than in the three great extended works of 1845–6: the Barcarolle Op 60, Polonaise-Fantasie Op 61 and Cello Sonata Op 65

In the summer of 1845, alongside new mazurkas and songs, the Barcarolle was written . Perhaps by coincidence, perhaps by design, the last of the three Mazurkas, Op. 59, composed in the key of F sharp minor, ends with a switch to the bright F sharp major. And it is in that same F sharp major – a rare key in Chopin – that the Barcarolle begins. It is also in shades of F sharp major (as the work’s main key) that the Barcarolle’s musical narrative proceeds, departing from it and returning to it again.

We do not know when and in what circumstances the idea for this music was conceived. Chopin never visited Venice. He had but a fleeting encounter with Italian landscapes and atmosphere on a boat trip from Marseilles to Genoa. A storm at sea was perhaps more likely to have impressed itself onto his memory of that fatiguing expedition than any image of the city. It is assumed that Chopin could have been given the idea of composing a barcarolle, as well as a prototype for its shape and character, by works in that genre which functioned in the current musical repertoire, especially in opera, and above all in Rossini and Auber. All the operatic barcarolles by those composers were well known to Chopin. He could not possibly have forgotten the barcarolles from Guilllaume Tell, La muette de Portici or Fra Diavolo.

The barcarolle genre was becoming increasingly popular in vocal and pianistic lyricism. We know that Chopin gave his pupils Mendelssohn’s Lieder ohne Worten to play. The sixth number in the first book of the Songs without Words bears the title ‘Venezianisches Gondellied’ Venetian boat song. This could certainly have been a path for Chopin into the convention of the nineteenth-century barcarolle. Yet in Chopin’s Barcarolle there are no references to either the historical tradition of the songs of the Venetian gondoliers (as do appear in Liszt’s ‘Venezia e Napoli’) or the banal idiom of the opera-salon barcarolle of the day, which would soon reach its pinnacle with the Barcarolle from Offenbach’s Les contes d’Hoffmann. In Chopin’s Barcarolle, beneath the cloak of the generic convention, we find music that encapsulates his supreme pianistic experience and the musical maturity that he had attained during this rather reflective phase, and at the same time music that echoes his experience of the whole Mediterranean south of Europe: the Italian songs of Lina Freppa, Bellini’s bel canto, the passionate Spanish songs of Pauline Viardot, which Chopin listened to in rapture, and the wild, but incredibly beautiful landscape of Majorca.

One peculiar, extraordinary moment comes at the point which Chopin defines with the words dolce sfogato and precedes with a lead-in filled with hushed mystery. That enigmatic, unfathomed dolce sfogato then starts to develop and bloom.

In his Notes on Chopin, André Gide went into raptures: ‘Sfogato, he wrote; has any other musician ever used this word, would he have ever had the desire, the need, to indicate the airing, the breath of breeze, which, interrupting the rhythm, contrary to all hope, comes freshening and perfuming the middle of his barcarolle?’

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2021/11/23/shunta-morimoto-takes-rome-by-storm/