Having just arrived back in Rome I was in time to hear Beatrice Rana who I last heard at the Proms in London, playing to 6000 people with many more listening via the BBC radio. Playing of a simplicity and natural musicality that brought to life Rachmaninov’s Paganini Rhapsody in the Royal Albert Hall with a freshness and refined beauty that revealed a much maligned work as a genial amalgam of chamber music proportions and not the usual barn storming rhetoric that this work has suffered for too long ! Fou Ts’ong used to say it is much easier to be intimate in a big space than it is in a small one.

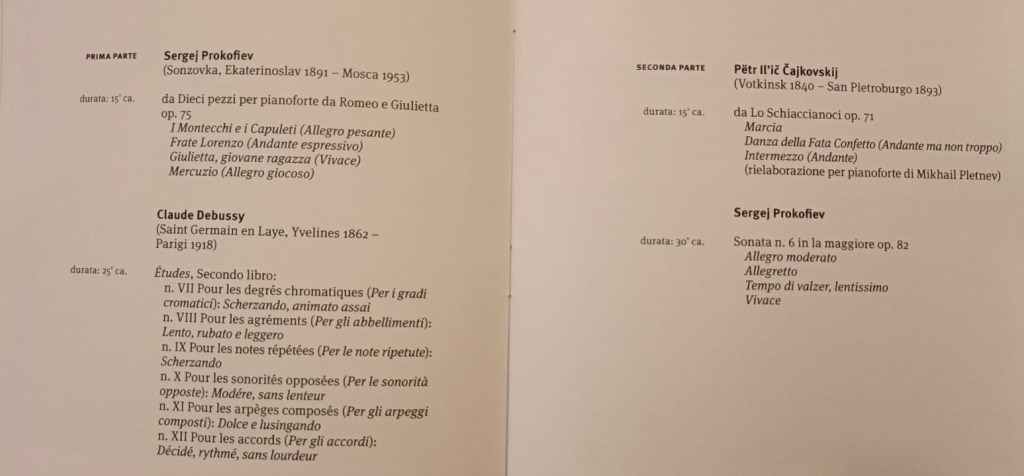

It was the same simplicity and refined beauty that she revealed in Rome. Having played the same recital in the past few days at San Carlo and La Scala it was hardly surprising to see the Sala Sinopoli in Rome selling out almost immediately in her adopted home of Rome. Luckily the Rai radio had their microphones at the ready to broadcast the concert live to the many, like me , excluded from such a sumptuous feast of music. Her playing seems to be so much more colourful and fearless these days with a hypnotic use of the pedals that adds a sonorous richness to her kaleidoscopic palette of sounds . Thanks to the superb radio technicians it could be savoured, maybe even more than in the hall. A courageous programme of Prokofiev, Tchaikovsky and Debussy especially when it is obvious now that Beatrice will soon experience the joy of motherhood. The Debussy Studies written in 1915 were much criticised because the genial invention towards the end of Debussy’s life broke away from the conventional music of the day and pointed to the future, as Liszt had done in the previous century. Debussy was a great admirer of Chopin and had even edited an edition of his works and so it was to the study that he turned for his final inspiration . Not those of the first book of Chopin op 10 but those of the second op 25 where Schumann’s description of the mazurkas as ‘canons covered in flowers ‘ could well apply here too. They are technical difficulties disguised with genial fantasy and turned into miniature tone poems . Considered now as Debussy’s finest work for piano they are rarely heard in the concert hall because of their transcendental difficulty and subtle intimacy. A refined mastery of poetic understanding and a piano technique of subtle whispered refinement not bombastic showmanship. Chromatic scales of jewel like precision and the chattering of extraordinary vibrancy as Beatrice allowed Debussy’s melody to appear like a mirage in a haze of undulating sounds . Sounds that unfolded with wistful elegance and mystery as ornaments were subtly covered in exquisite pedal effects of whispered intimacy. Repeated notes that were mere vibrations gradually gaining in weight and revealing themselves with a frisson of reverberating sounds. There was magic in the air as arpeggios wafted into the air like flowers gently opening in exotic warm climes . And finally the dynamic drive of chords shaped with fearless mastery, coloured with a curiously inquisitive questioning central episode before the exhilarating and liberating final flourishes.

After the interval Beatrice had chosen just three pieces from Pletnev’s ‘Nutcracker’ to calm and caress us before the extraordinary blast of the most violently disturbed of Prokofiev’s Trilogy of War Sonatas. Mikhail Pletnev the great piano virtuoso, winner of the Tchaikowsky competition and feted worldwide, had written a suite for piano from the Ballet ‘The Nutcracker.’ I believe he even played the work as part of his prize winning recital in 1978 at the age of 21. Now in his Indian Summer where his poetic search for the perfect legato still shows the refined sensibility of the youthful virtuoso which is now reduced to a mere shadow.

Beatrice chose just three of the seven pieces which she played with scintillating clarity and brilliance, bringing a luminous radiance of childlike simplicity to the ‘Sugar Plum Fairy’ before the sumptuous beauty of the Intermezzo, which she played with orchestral sounds of Philadelphian richness. It should be mentioned that Taneyev, a friend of the composer, had also made a virtuoso transcription of the Ballet. Tchaikovsky admired it enormously but had to make a simpler one for the less endowed pianists who prepared the dancers for the stage! This ‘other’ transcription seems to have been completely forgotten in the concert hall but is much admired by many inquisitive musicians. I expect Beatrice knows it ,of course, and was searching for a suitable combination with Prokofiev. As she said, in her short but very interesting Green Room interview, immediately after the concert, her programmes are a very well pondered musical journey. A moment in which the performer can also be an informer, for a public that one should never underestimate!

It was to Prokofiev that she turned to open and close this remarkable recital. Four scenes from his ballet ‘Romeo and Juliet’ opened the concert. Imposing sumptuous sounds from the very first note of the ‘Montagues and Capulets’, playing with extraordinary freedom and authority with a palette of sounds helped by a generous use of the sustaining pedal and a glorious beauty to the melodic line that follows with inner voices of subtle insinuation. Followed by an impish display of ‘fingerfertigkeit’ with a real teasing energy of intoxication. An arresting opening to a programme which, as she said in her interview, was a domestic tragedy and would finish with a worldwide catastrophe.

Prokofiev’s Sixth Sonata was the main work on the programme and she unleashed it on us with fearless abandon and breathtaking dynamic drive. Prokofiev’s demonic insistence played out with extraordinary virtuosity and architectural understanding. A burning cauldron of sounds to which the shrieks of pain and anguish would be nailed with merciless brutality. Beatrice had seen the vision that this sonata depicts of the brutality and suffering that conflict can bring as she described it in sounds with breathtaking mastery. The seemingly innocent trot of the ‘Allegretto’ was short lived as all sorts of surprises are imposed on it with beguiling insinuation. A ‘tempo di valzer,lentissimo’, was a languid outpouring of beauty and an oasis of beauty on this field of combat but soon built in passionate intensity as Prokofiev tries to find a reason for such cruelty. There was real menace to the ‘Vivace’ last movement that Beatrice played with fearless abandon and frenzy. A real boiling pot of sounds out of which Prokofiev places his leit motif with devastating effect. This was truly a masterly performance and an amazing ‘tour de force’ especially as Beatrice was not alone at the keyboard this time!

Scriabin’s beautiful study op 2 was calming balm after such violence and she played it with a freedom and sense of colour that I have never heard from her before. She could feel that the audience were following every sound with rapt attention and she lead them into a better place that is found in the paradise of sumptuous timelessness of a different age. An ovation realised yet another encore from Beatrice who must have been doubly exhausted after such a daunting programme. Like all great artists she has a reserve of energy that she shared with us in another study by Debussy of purity and scintillating brilliance finishing with an impish whispered farewell.

First composed in 1935, Romeo and Juliet was substantially revised for its Soviet premiere in early 1940. Prokofiev made from the ballet three orchestral suites and a suite for solo piano.

Moving back to the Soviet Union in 1933 following a self-imposed exile of fifteen years, Sergei Prokofiev suddenly found a new sense of purpose as a composer. Composed in a burst of frenzied activity during the summer of 1935, Romeo and Juliet nevertheless proved to be controversial even before a note of the music was heard in public. After the directors of the Bolshoi Ballet in Moscow read through the score and pronounced it “impossible to dance to,” Prokofiev, in a cold rage, extracted two suites from the ballet in 1936. Guessing—correctly—that the suites would create a demand to hear the work in its entirety, Prokofiev soon had the pleasure of seeing the Bolshoi and its bitter rival, the Kirov Ballet of Leningrad, vie for the right of the first production. The honor of the first Soviet performance fell to the Kirov on January 11, 1940, some two years after Romeo and Juliet had been given its world premiere in Brno, Czechoslovakia, in December of 1938.

In spite of its considerable length–at nearly two and a half hours, it is the most ambitious of Prokofiev’s non-operatic scores—Romeo and Juliet is a carefully molded musical and emotional structure in which the music is not only intimately related to the stage action but is also a self-referential dramatic construct which can readily stand on its own.

“Montagues and Capulets” is made up of two widely spaced moments from the ballet: the slow, threatening music which accompanies the Duke’s order that the warring families must cease fighting on pain of death, and, from the ballroom scene, the menacing and slightly oafish Dance of the Knights, which hints that the gentleman may have forgotten to take off their armor.

The cleric “Friar Laurence” is represented by a pair of themes, one in bassoons, tuba and harp, the other in divided cellos.

“The Young Juliet” brilliantly captures the rapidly changing moods of the character’s adolescent personality.

The “Death of Tybalt” forms the shattering conclusion of Act II. The music first describes the savage yet strangely high-spirited fight in which Mercutio is slain by Tybalt—neither fully aware of the seriousness of the situation until it is too late—and then the furious duel, underscored by sharp, percussive jabs and brutal dissonances, in which Romeo avenges Mercutio’s death. Heavy, measured thuds of the timpani herald Tybalt’s funeral procession, bringing the scene to a close.

Prokofiev reduced selected music from the ballet as Romeo and Juliet: Ten Pieces for Piano, Op. 75, which were performed in 1936 and 1937.

Romeo and Juliet before Parting

Folk Dance

Scene: The Street Awakens

Minuet: Arrival of the Guests

Juliet as a Young Girl

Masquers

Montagues and Capulets

Friar Laurence

Mercutio

Dance of the Girls with Lilies

Prokofiev’s Piano Sonata No. 6 in A major, Op. 82 is the first of the “War Sonatas”. It was composed in 1940 and first performed on 8 April of that year in Moscow, with the composer at the piano.It is in four movements

Allegro moderato (in A major)

Allegretto (in E major)

Tempo di valzer lentissimo (in C major)

Vivace (in A minor, ending in A major)