I have known Julian since he came to the attention of the public as an unknown 16 year old who had won top prize at the much coveted Long-Thibaud-Crespin competition in Paris where Stephen Kovacevich had been President of the jury. Thanks to Dr Mather and his team I have been able to follow his career, also thanks to Talent Unlimited of Canan Maxton that has given him a platform in which to grow and refine his extraordinary intellectual and musical talents. An interruption to his studies at Oxford University to become assistant to the remarkable and notoriously severe pedagogue Rena Shereshevskaya has been just part of the long journey of this eclectic thinking musician. Completing his studies in Oxford he has been on the competition circuit where his remarkable talent has grown and become recognised as a quite unique musical personality. A mature pianistic mastery that I was aware of with his superb performance of Bartòk Third Concerto as he arrived in the final of the Leeds where he had interrupted his honeymoon to take part unexpectedly, having been placed on the reserve list! Today I was reminded of Richard Goode as I watched this eclectic artist who thinks more of the music than himself as he literally devours the pianistic repertoire and brings to our notice works that have been neglected for too long. He is able to synthesise in just a few well chosen words, the scores he is presenting, that illuminate the music that pours from his fingers with remarkable mastery and fluidity. A unique panorama of French music that was so fascinating and convincingly played that it had me searching for more information about some of the composers from D’Anglebert to De Séverac.

D’Anglebert’s Prélude from his Suite in G. Music without bar lines that was to be a great influence on all those that came after him. Julian brought it to life with an inner intensity and nobility of fluidity and clarity giving an architectural shape to music that I have never heard in a piano in recital before.

The two pieces by Rameau are well know works often played by Sokolov and others as encores, but rarely included in a panorama tracing the evolution of the remarkable French keyboard school.

‘Le Coucou’ is often given to students to acquire a finger technique as they pass on upwards from their Grade 5 ! Julian showed us today what real ‘fingerfertigkeit’ can mean as he brought this work alive not only with scintillating brilliance and glowing fluidity but with a sense of character where Rameau’s busy little ‘Coucou’ could be relished as only a great artist could show us.

There was a call to arms in ‘Le Rappel’, where Julian had warned us of the double meaning of these particular birds. Piercing sounds of great clarity with trills glistening like tightly wound springs and a forward drive of exhilaration and sparkling brilliance.

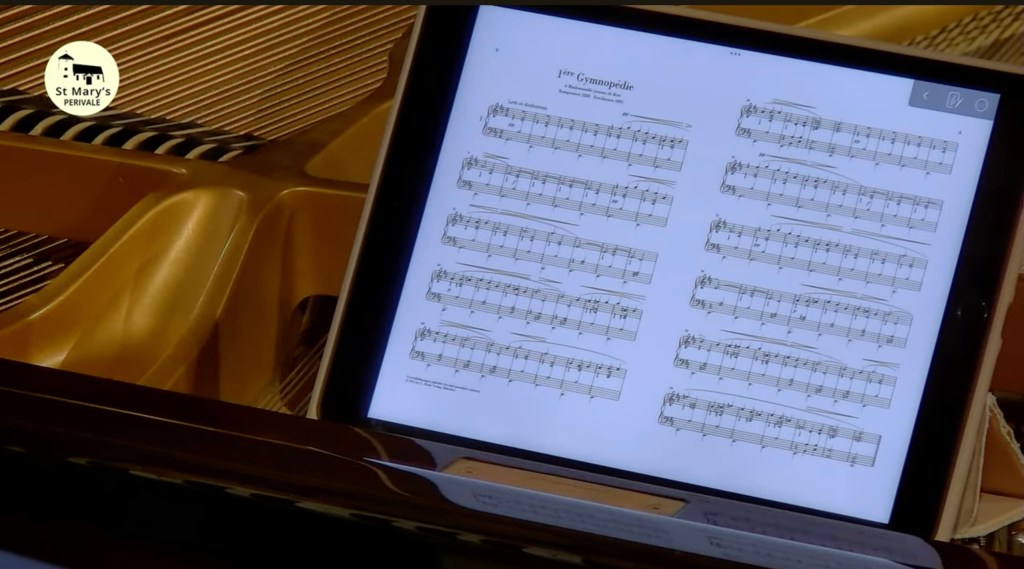

Satie as Julian told us liked to do nothing, and his music is indeed very sparse on the page. Like Debussy’s ‘Canope’, these few notes, when played with poetic understanding and masterly control, can convey the impression of stillness and chiselled beauty of these ancient relics that they describe so atmospherically.

Julian is quite right when he says that Fauré’s piano music has not been given then place in the concert repertoire that it deserves. Even if Julian is a year late to celebrate the centenary of Fauré’s death it is never too late, when played with the mastery, beauty and understanding that Julian demonstrated today . A ‘Valse Caprice’ of brilliance with a glowing jeux perlé of dynamic drive and a chameleonic range of sounds. Cascades of notes played with the beauty and elegance of pianists of the Golden age of playing when the piano could be transformed into a magic box of sounds with balance and style instead of force and showmanship. And what style Julian brought to this ‘Valse’ and the perpetuum mobile of the ‘Impromptu’ op 31 that he linked it with! The ‘Valse’ had a pulsating rhythmic energy that seemed to possess his entire body as he swayed and moved with the music, giving a natural fluidity to the sounds he produced. Never percussive but with a glowing beauty of ravishingly subtle sounds as he moved as a singer would breathe. The ‘Impromptu’ was an enlightened partner and is slightly better known in the concert hall for the beautiful central episode of radiance and beauty that is revealed, inbetween the ever more bewitching lightness of the Impromptu as it weaves it’s way inexorably forward.

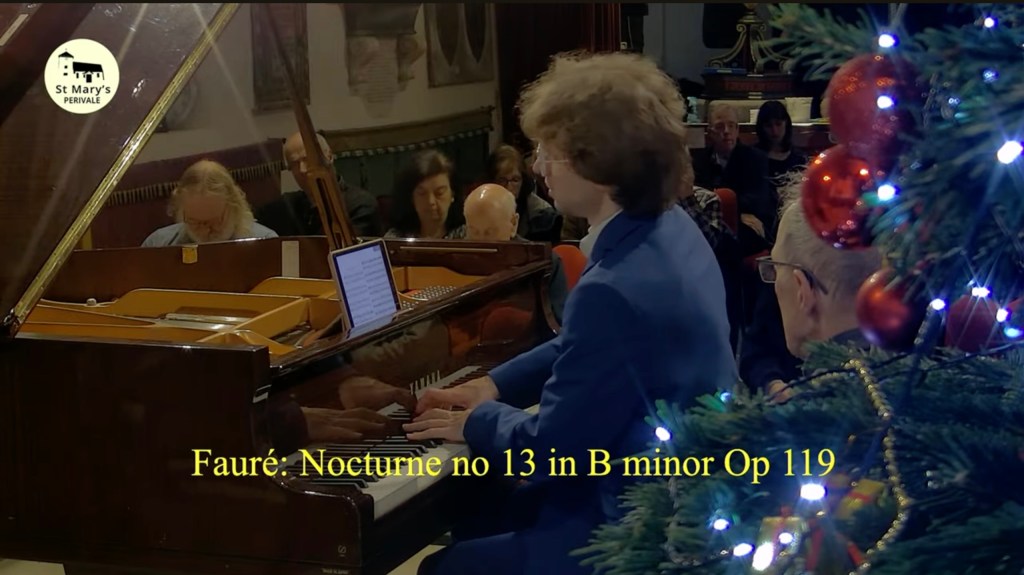

Two nocturnes, the first and the last, were placed together, side by side as my teacher Vlado Perlemuter would do in his many recitals in my series in Rome. Vlado even wanted me to announce before he played them that he had lived in the same street as Fauré ( who was director of the Paris Conservatoire ) and he would send these nocturnes over with the ink still wet on the page for the young prodigy of Cortot to try out for him to hear.

There was a chiselled beauty to the Nocturne in E flat minor that Julian played with simplicity and poignant beauty. As Perlemuter would always point out, playing with sentiment but never sentimentality. There is a strength to Fauré’s music that comes from his inner faith and his dedication to the grandeur of the organ. The ominous central episode was played with masterly control of the pedal where luminosity and orchestral clarity could live happily together. There was magic in the air as the melodic line was shadowed high up on the keyboard ( another manual on the organ ) with Julian’s arms accommodating with masterly ease this extraordinary doubling of the melodic line as it builds in intensity for a tone poem of glowing beauty and radiance.

The B minor Nocturne has long been considered a masterpiece by many great pianists . Horowitz in particular in his Indian Summer of recitals would play it with great intensity as Julian did today. A seamless, mellifluous outpouring of daring harmonic audacity, with a continuous outpouring of sumptuous sounds of poignant significance. A composer who by now, was deaf and blind but could still issue the great cry of ecstasy of a true believer.

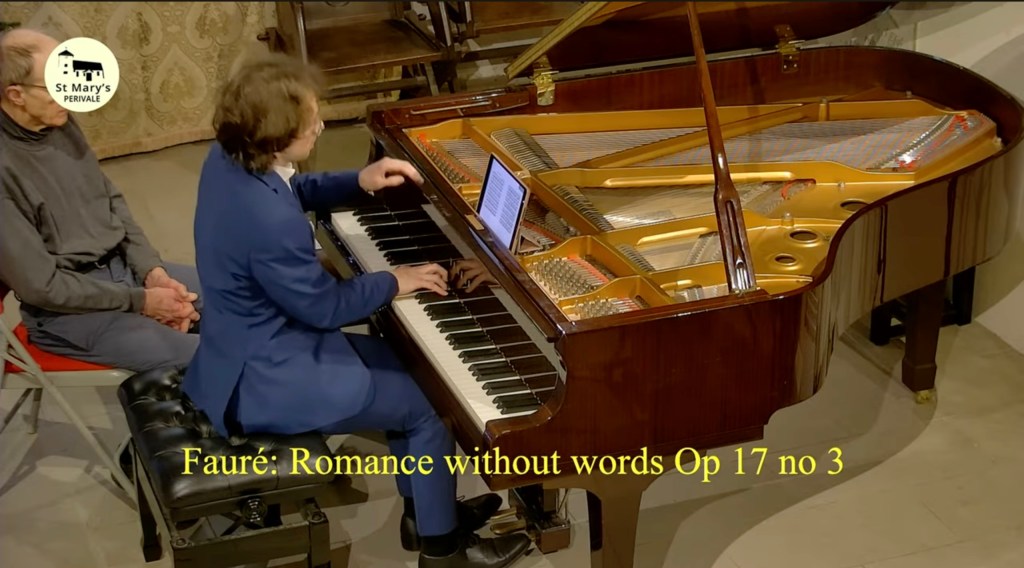

Cortot described Fauré’s Romances as his ‘sins of youth ‘ and they are very simple beautiful pieces of popular appeal. As Julian said :’one could imagine a young lady showing off her new attire ready to be admired ‘. It was played with touching sensitivity and a nostalgic beguiling beauty shaped with the elasticity of a great Bel Canto artist .

Séverac was described by Julian as the country bumpkin of French music and it was an apt description of a composer of great originality who could paint a simple picture in sound. In this piece it is the horse and cart arriving in Cerdagne.The Spanish part of France that is all light and brilliance where Julian’s playing was very descriptive, as we could almost see this horse and cart lazily making it’s way ahead.

Roussel was described by Julian as a cross between Debussy and Prokofiev. The composer had been a sailor before dedicating himself to composition and sea songs and the clanking of ropes and chains can be discerned usually in his compositions. In this particular ‘Sicilienne’ though, there was a beautiful effusion of romantic sounds played with freedom and conviction. The quiet ending suddenly becoming the vision of Jersey that inspired Debussy to write his ‘L’Isle Joyeuse’ whilst holidaying in Eastbourne.

A remarkable performance of burning intensity building into a frenzy of passionate sounds. A wonderful sense of legato as in a momentary oasis of calm a melody unwound that was to taken us to the climax played by Julian with the same passionate intensity that I remember from Annie Fischer’s memorable performance many years ago as she played it as an encore in Rome.

As an encore Julian chose an work by a lady composer. Augusta Holmès is the lady that had stolen Saint- Saëns’ heart much to the annoyance of César Franck. A little piece chosen by Julian , one of the very few she had written for piano, and it was a fitting end to such an illuminating and eclectic programme from a young man who has been transformed from a gifted teenager into a unique thinking artist. .

Julian Trevelyan is a concert pianist who performs regularly throughout Europe and in the UK. He is 26 years old, and moved to France after winning the 2015 Long-Thibaud-Crespin international competition at the age of 16, becoming the youngest prize-winner in the competition’s history. He has since won prizes at international piano competitions such as the Leeds, Géza Anda & Horowitz.

He has appeared as a piano Soloist with the BBC National Orchestra of Wales, City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, Royal Liverpool Philharmonic, London Mozart Players & Worthing Symphony Orchestra in the UK. He has played with the Orchestre de Chambre de Paris, Orchestre national du capitole de Toulouse, Orchestre de Picardie, Orchestre de la Suisse Romandie, Musikkolegium Winterthur Tonhalle Zurich, Moscow Chamber Orchestra, State Academic Symphony Orchestra of Russia & St Petersburg Philharmonic, NMA Academic Symphony Orchestra, Sofia Soloists, I Pomeriggi Musicali, ORF Wien, Danubia Obuda Orchestra & Baden-Baden Philharmonic.

Julian has made recordings with the Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra, the London Mozart Players and the BBC National Orchestra of Wales. The first CD under the baton of Christian Zacharias was released in 2022 with the label ALPHA: Mozart’s Concertos Nos. 23 and 24. Further releases under the baton of Howard Griffiths will follow in 2025.

Julian is the assisant of Rena Shereshevskaya at the École Normale de Musique de Paris “Alfred Cortot”. He studied in London with Christopher Elton and Elizabeth Altman. As a teenager he was part of Aldeburgh Young Musicians. This fuelled his love for contemporary music, where he premiered new music every month. He cares about supporting female and living composers and is pianist and composer in residence with Ensemble Dynamique.

Augusta Mary Anne Holmès (16 December 1847 – 28 January 1903) was a French composer of Irish descent. In 1871 and became a French national and added the accent to her last name.She also published music under the name Hermann Zenta, because women in European society at that time were not taken seriously as artists and were discouraged from publishing.Despite showing talent at the piano, she was not allowed to study at the Paris Conservatoire but took lessons privately. She developed her piano playing under the tutelage of local pianist Mademoiselle Peyronnet, the organist of Versailles Cathedral ,Henri Lambert, and Hyacinthe Klosé. Also, she showed some of her earlier compositions to Franz Liszt and around 1876, she became a pupil of César Franck , whom she considered her real master.

Camille Saint- Saëns was among the many artists – musicians, poets, painters – who became enamoured of her and fell in love with her, eventually proposing marriage, but he was turned down.Later, he wrote of Holmès in the journal Harmonie et Mélodie: “Like children, women have no idea of obstacles, and their willpower breaks all barriers. Mademoiselle Holmès is a woman, an extremist.”

Her Piano music includes :

Rêverie tzigane (1887) Ce qu’on entendit dans la nuit de Noël (1890) Ciseau d’hiver (1892)

Albert Charles Paul Marie Roussel (5 April 1869 – 23 August 1937) He spent seven years as a midshipman, turned to music as an adult, and became one of the most prominent French composers of the interwar period . His early works were strongly influenced by Debussy and Ravel , turning later towards neoclassiciam.Roussel will never attain the popularity of Debussy or Ravel, as his work lacks sensuous appeal….yet he was an important and compelling French composer. Upon repeated listening, his music becomes more and more intriguing because of its subtle rhythmic vitality. He can be alternately brilliant, astringent, tender, biting, dry, and humorous. His splendid Suite for Piano (Op. 14, 1911) shows his mastery of old dance forms. The ballet scores Le Festin de l’araignée(The Spider’s Feast Op. 17, 1913) and Bacchus et Ariane (Op. 43, 1931) are vibrant and pictorial, while the Third and Fourth Symphonies are among the finest contributions to the French symphony. His piano music includes : Des heures passent, Op. 1 (1898), Conte à la poupée (1904), Rustiques, Op. 5 (1906), Suite in F-sharp minor, Op. 14 (1910), Petite canon perpetuel (1913), Sonatine, Op. 16 (1914), Doute (1919), L’Accueil des Muses [in memoriam Debussy] (1920), Prelude and Fugue, Op. 46 (1932), Three Pieces, Op. 49 (1933)

Marie-Joseph Alexandre Déodat de Séverac 20 July 1872 – 24 March 1921) was a French composer born in the Haute-Garonne, descended from a noble family, profoundly influenced by the musical traditions of his native Languedoc. Séverac is noted for his vocal and choral music, which includes settings of verse in Occitan (the historic language of Languedoc ) and Catalan (the historic language of Roussillon) as well as French poems by Verlaine and Baudelaire. His compositions for solo piano have also won critical acclaim, and many of them were titled as pictorial evocations and published in the collections Chant de la terre, En Languedoc, and En vacances.

A popular example of his work is The Old Musical Box (“Où l’on entend une vieille boîte à musique”, from En vacances). His masterpiece, however, is the piano suite Cerdaña (written 1904–1911), filled with the local colour of Languedoc.

Jean-Henri d’Anglebert (baptised 1 April 1629 – 23 April 1691) was a French composer, harpsichordist and organist and was one of the foremost keyboard composers of his day.

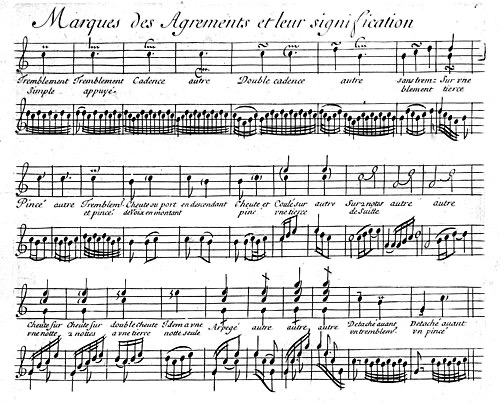

D’Anglebert’s principal work is a collection of four harpsichord suites published in 1689 in Paris under the title Pièces de clavecin. The volume is dedicated to Marie Anne de Bourbon , a talented amateur harpsichordist who later studied under Couperin. Apart from its contents, which represents some of the finest achievements of the French harpsichord school (and shows, among other things, D’Anglebert’s thorough mastery of counterpoint and his substantial contribution to the genre of unmeasured prelude ), Pièces de clavecin is historically important on several other counts. The collection was beautifully engraved with utmost care, which set a new standard for music engraving. Furthermore, D’Anglebert’s table of ornaments is the most sophisticated before Couperin’s (which only appeared a quarter of a century later, in 1713). It formed the basis of J.S.Bach’s own table of ornaments (Bach copied D’Anglebert’s table ca. 1710), and provided a model for other composers, including Rameau. Finally, D’Anglebert’s original pieces are presented together with his arrangements of Lully’s orchestral works. D’Anglebert’s arrangements are, once again, some of the finest pieces in that genre, and show him experimenting with texture to achieve an orchestral sonority.

Most of D’Anglebert’s other pieces survive in two manuscripts, one of which contains, apart from the usual dances, harpsichord arrangements of lute pieces by composers such as Ennemond and Denis Gaultier, and René Mesangeau . They are unique pieces, for no such arrangements by other major French harpsichord composers are known. The second manuscript contains even more experimental pieces by D’Anglebert, in which he tried to invent a tablature-like notation for keyboard music to simplify the notation of style brisé textures.D’Anglebert died on 23 April 1691 and his only published work, Pièces de clavecin, appeared just two years before, in 1689. The rest of his music—mostly harpsichord works, but also five fugues and a quatuor for organ—survives in manuscripts.