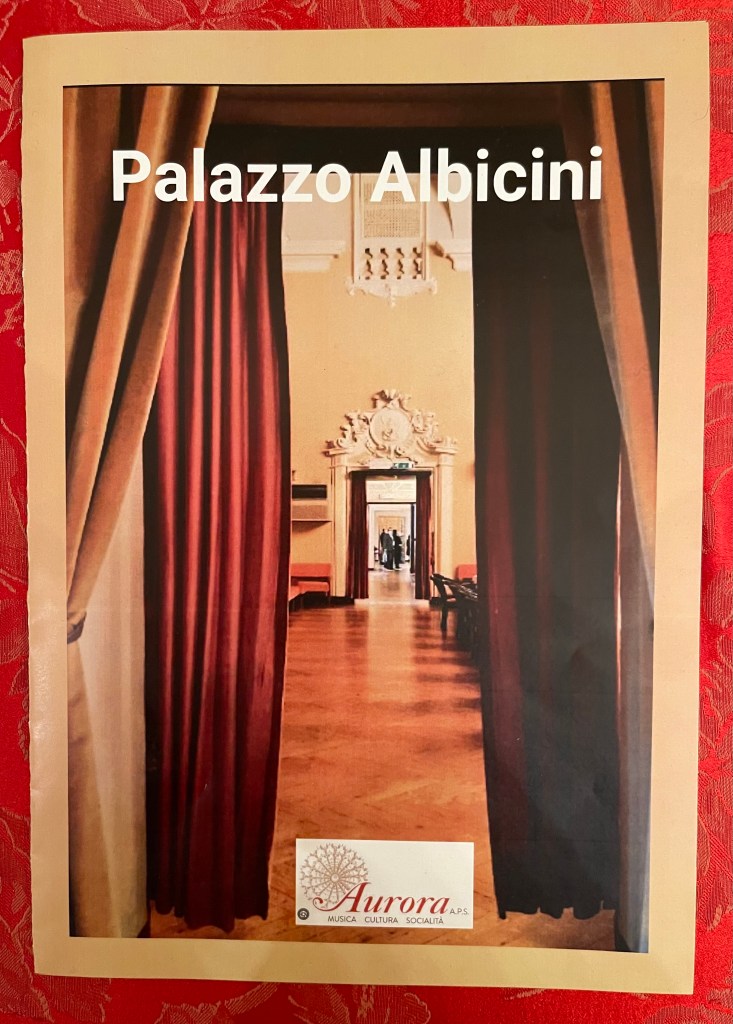

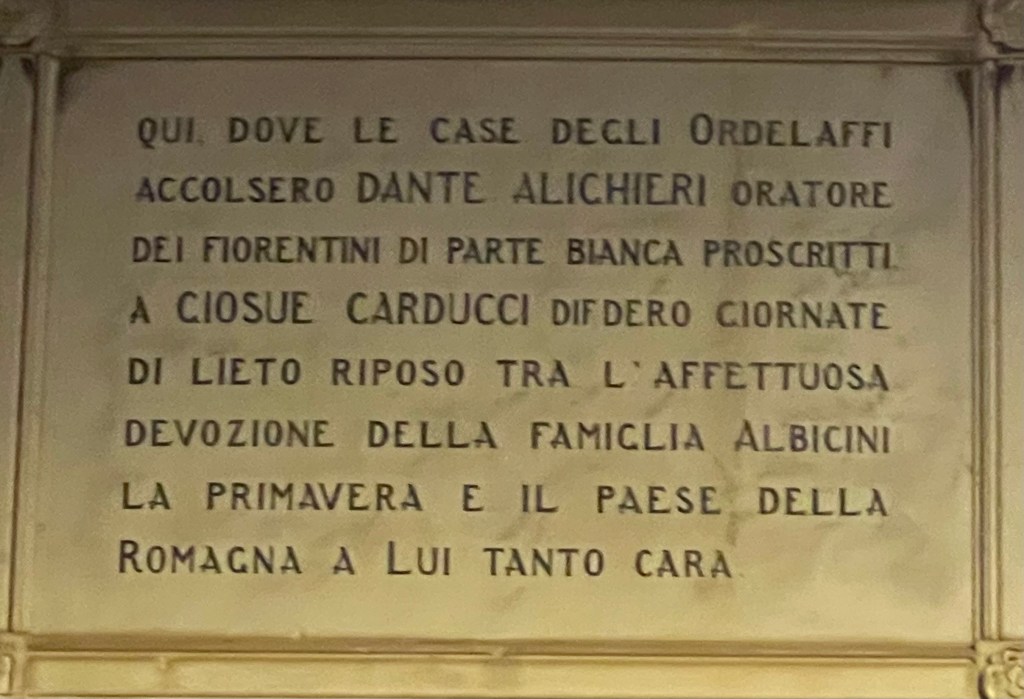

Gabrielé Sutkuté giving her second recital in Italy in Palazzo Albicini in Forlì. Moving on to Forlì after the Harold Acton Library in Florence for a concert in the new series that the Tuccia’s have organised to celebrate their legendary citizen Guido Agosti. A disciple of Busoni and one of the great musicians of the last century celebrated for over thirty years at the Chigiana in Siena where he held court every summer. He was born and is buried in Forlì. https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2025/04/14/homage-to-guido-agosti-gala-piano-series-in-forli-2025/

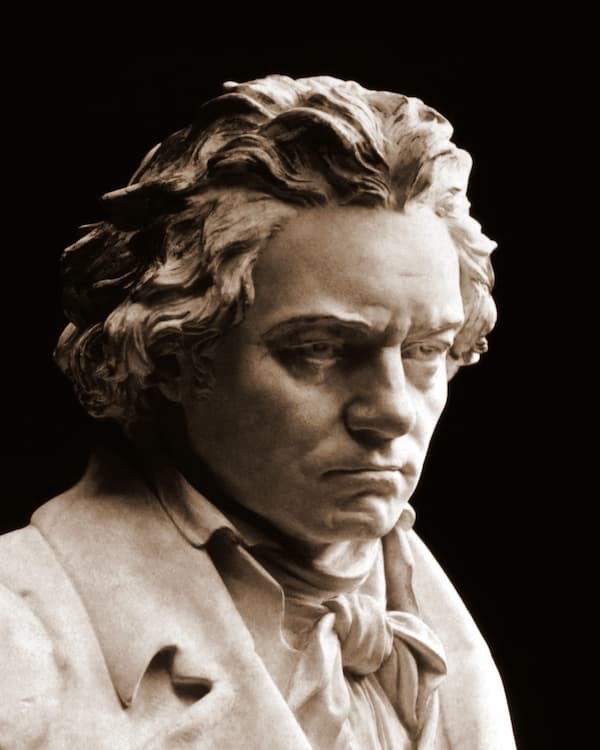

Ludwig van Beethoven – Seven Bagatelles, Op. 33

Karol Szymanowski – Variations in B-flat minor, Op. 3

Claude Debussy – Images, Book 1, L. 110:

I. Reflets dans l’ eau

II. Hommage à Rameau

III. Mouvement

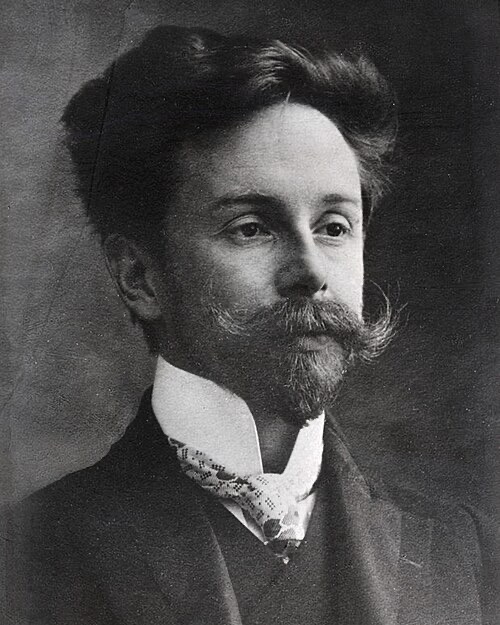

Alexander Scriabin – Piano Sonata No. 4 in F-sharp major, Op. 30

Beginning with the multi faceted trifles that make up Beethoven’s youthful Bagatelles op 33 and ending with Papà Haydn , his teacher, with the simple purity of the Menuet and Trio from his Sonata in B minor.

A moment of sublime reflection after the turbulence of Scriabin’s search for his star in the Fourth Sonata or the youthful exuberance of the Variations op 3 by Szymanowski.

Debussy’s Images Book 1 were an oasis of glowing whispered beauty where Gabrielé’s refined sensibility turned these three tone poems into a scintillating stream of golden sounds with a palette of subtle colours.

Beethoven’s seven bagatelles were played with extraordinary characterisation and subtle multifaceted sounds that brought these miniature jewels vividly to life. Starting with the very delicate and beautifully shaped first piece played with a beguiling ornamentation of bel canto freedom. The second showed Beethoven in ‘slap stick’ mood poking fun at us from all unexpected directions. Gabrielé visibly enjoying this almost improvised freedom before the pastoral peace of the third where the music was allowed to flow with such natural fluidity. The fourth too continued this peaceful journey with the tranquil beauty and delicacy of the countryside. Streams of notes where the busy meanderings of the fifth were paraded over the entire keyboard with Beethoven’s false ending having the last laugh,much to Gabrielé’s glee. A disarming almost Mozartian purity of simplicity and beauty before the vibrant agitation of the last bagatelle where Gabrielé built the vibrant tension to a fever pitch of exhilaration.

The Szymanowski Variations are an early work full of youthful passions and virtuosity but also moments of poetic beauty of almost Brahmsian significance. A series of variations that unfolded with masterly control and a vast range of emotions. Showers of golden sounds flowed from Gabrielé’s fingers with a jeux perlé that accompanied the theme hidden away within the depths.It was to explode at the end in a triumphant outpouring of sumptuous sounds with quite considerable technical mastery. There was also great delicacy as the variations opened with ever more romantic intensity. Even a waltz with all the charm of salon pianists of the Golden age when pianists could let their hair down with refined good taste . A romantic outpouring that Gabrielé imbued with passionate involvement as she brought this rarely played work back to the concert hall where it has been lacking for too long.

‘Reflets dans l’eau’ the first of Debussy’s Images allowed Gabrielé to find whispered sounds where notes just disappeared as the became streams of sounds of delicacy and fluidity. Washes of sounds on which the melodic line was allowed to glow with piercing radiance leading to an ending of pure atmospheric magic. A palette of sounds of whispered delicacy but without ever loosing the sense of line as she possesses a control of sound that reminds me of the first appearance of Sviatoslav Richter in the west. We were astonished not by the dynamic drive and animal energy of this great pianist but by how quietly he could play and with what extraordinary control of sound, endless variations of piano and pianissimo that he did not project outwards but drew us inwards to his private world of magical sounds. Gabrielé too ,succeeded in drawing us in to overhear the magic that she could find hidden within this instrument of fine vintage. There was an unusually visionary beauty to ‘Hommage a Rameau’ where nobility and mystery were combined with aristocratic control and at times burning intensity. ‘Mouvement’ was a tour de force of undulating sounds resounding around the keyboard with continual vibrancy. Building to a climax where Thalberg’s three handed technique came into play as Gabrielé managed to shape the melodic chords, notes flying all around with playing of total commitment and hypnotic dynamic drive.

Scriabin’s early Fourth Sonata found an ideal interpreter in Gabrielé and although only her first public performance she had played it in America last week to her mentor Gabriella Montero. Sometimes a word of two can illuminate work in progress and as Gabrielé told us, la Montero had told her that the opening should be played with the idea of being charmed by someone who as yet is not completely convincing! Gabrielé played with glowing radiance the opening with wonderful streams of filigree sounds accompanying the melodic line before arriving at a series of dry quiet questioning chords before bursting into the dynamic fleeting drive of the second movement. Gabrielé with natural swimming like movements allowed this outpouring to be shaped with lightweight brilliance as it gradually lead to the ultimate climax and the vision of the ‘star’ that was so much part of Scriabin’s sound world.

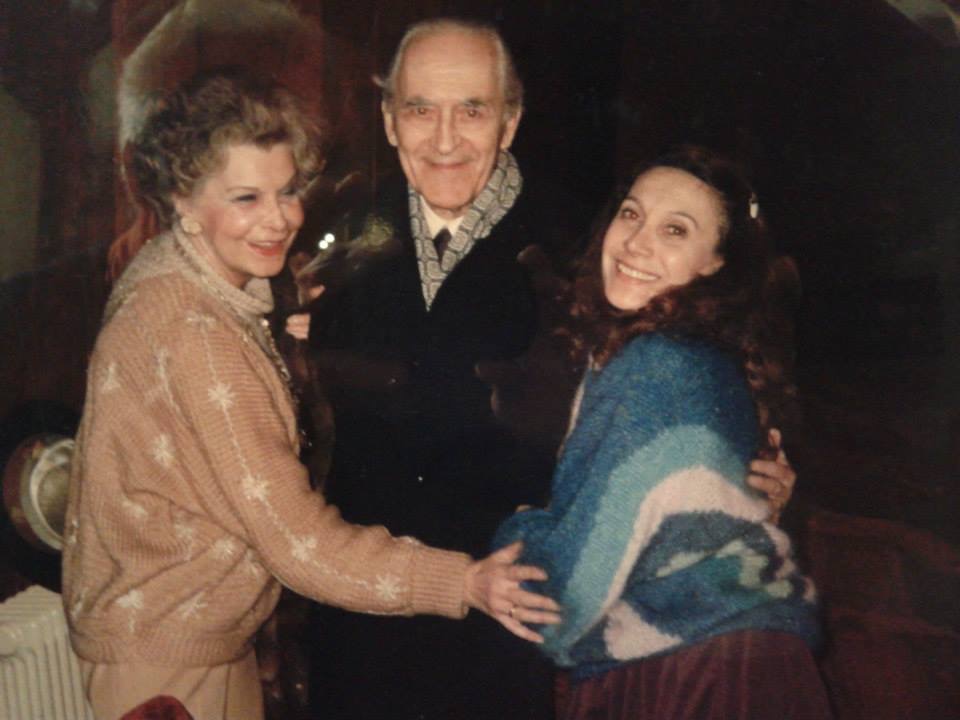

Agosti was my teacher and in particular that of Leslie Howard, and by coincidence we are both Artistic directors (together with Elena Vorotko) of the Keyboard Trust. I met my wife via the Agosti’s in Siena and we had our wedding breakfast in their summer home there in 1984.I carry Agosti and my late wife around with me always on my ‘phone ( that is the 21st century equivalent of a locket around one’s neck). Nicolò Tuccia I have long admired for his skill at contacting people and being his own impresario. He and his companion, Chiara Bolognesi, really do know what Menuhin used to describe as ‘mutual anticipation’, as they are ready to share all their discoveries with other colleagues, old and young, who do not possess their skills! So it is that a collaboration with the Keyboard Trust was instigated, and this first concert with Gabrielé Sutkutè was born on ‘wings of song’.

I am sure that Agosti who is nearby, and we will visit this morning, will be looking on with approval and happy to know that ,at last, his fellow citizens can share his integrity and humility, which the world appreciated for his lifetime, as they listen to musicians selected by the Keyboard Trust. These are true interpreters and certainly not the entertainers where the idea of quantity rather than quality is being too readily accepted in the high speed lifestyle of this twenty-first century.

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2024/01/03/forli-pays-homage-to-guido-agosti/

It was Fou Ts’ong who used to tell me that it is far easier to be intimate in a big hall than in a small one. Of course the warmth and beauty of the Harold Acton Library brings another meaning to intimate music making in Florence, but this sumptuous ballroom/concert hall in Forlì with its raised stage added another dimension to Gabrielè’s programme.

A fluidity and sense of communication that she herself could feel as the music took flight and arrived with the same intensity with which it had been born. It is like an actor who knows how to use his diaphragm (which is how I met my future wife, as I helped Lydia Stix Agosti to train actors how to breathe like a singer ), where the human word arrives with the same intensity in the first row as it does in the very last. It creates a feeling of communication between the public and the performer where they become involved together in the act of creation. Today Gabrielé was stimulated by this unexpected complicity as she rose to the occasion with performances even more exciting and beautiful than in that Room with a View.

She was so exhilarated at the end of the concert that she risked playing a Gershwin Prelude as an encore which she had only just managed to memorised in time. Of course her success was complete and she had to play a second encore, even if by this time restaurants in Forlì were about to close!

Haydn’s slow movement ,played with even more purity and grace than in Florence, completed an evening of sumptuous music making, and as Gabrielé confided, her penultimate concert for 2025.

She has already been invited back to Florence in 2026 and I am sure Forlì will welcome her back with open arms after this ‘enchanted’ evening. Italy ,the Museum of the World as Rostropovich describe it , awaits her return!

Gabrielė has performed in prestigious venues throughout Europe, including Wigmore Hall, Cadogan Hall, Steinway Hall UK, the Musikhuset Aarhus, and Lithuanian National Philharmonic.

In addition to being a soloist, Gabrielė frequently performs with chamber ensembles and symphony orchestras. This year, she performed Grieg’s Piano Concerto with the Grammy-nominated Kaunas Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Markus Huber. In 2023, Gabrielė performed this Concerto with the YMSO at the Cadogan Hall, conducted by James Blair. She was also invited to play with the renowned Kaunas String Quartet in Lithuania twice.

Gabrielė is a winner of twenty international piano competitions where she also received numerous special awards.

Here is a short clip of Gabrielė playing Haydn: https://youtu.be/jAt5f2TsEJY

Bagatelles reflect Beethoven’s diverse compositional cosmos in miniature and span almost his entire oeuvre from 1801/02 to 1824/25. In terms of playing technique, they range from moderate dexterity to demanding virtuosity.

In addition to the well-known collections Opp.33, 119 and 126, ten more pieces were found after Beethoven’s death in an envelope labelled “Bagatelles”. These included the revised version of “Für Elise” as well as two further revisions of bagatelles which appear here in print for the first time. For a long time it was assumed that Beethoven reworked seven older pieces for his op. 33, published in 1803. But in the meantime it has been determined that all the surviving sketches came into being in 1801/02, and that the autograph dates from 1802. The fact that the composer wrote such bagatelles for amateurs in temporal proximity to the demanding Piano Sonatas op. 31 may at first glance be unsettling. But the pieces, in simple dance and song forms, display remarkable refinement. The collection, which already appeared in innumerable editions during Beethoven’s lifetime, enjoys great popularity to the present day, not least because – apart from the technically more demanding no. 5 – all the pieces are of medium difficulty, and thus are also accessible to proficient amateurs.Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827), the builder of imposing monuments for the keyboard required compositional diversions, needed to work from modest rather than mammoth blueprints. Apart from the several sonatas in which a relaxation of supreme striving is apparent, there are those pieces that are determinedly “small,” little things, or as Beethoven called them, Bagatelles, or Kleinigkeiten. An early set of the composer’s “little bits,” seven in number, were published in 1803 as Op. 33. Eleven pieces, Op. 119, came out in 1820, and the six of Op. 126, the last of his Bagatelles, were composed around 1823, the year he was finishing the Ninth Symphony, the Missa solemnis, and the Diabelli Variations for piano.

In regard to the Bagatelles, Eric Blom (1888-1959), the distinguished English writer on music and a Beethoven scholar, says that, in spite of their modest size [or perhaps because of it], the Bagatelles “reveal [Beethoven’s] character more intimately than anything else he ever wrote. They are,” he continues, “if anything in music can be, self-portraits, whereas his larger compositions express not so much personal moods as ideal conceptions requiring sustained thought and an unchanging emotional disposition for many day or weeks – indeed in Beethoven’s case sometimes years. But these short pieces could be dashed off by the composer, whatever he felt like at the moment, while the fit was on him. No doubt,” Blom concedes [and well he should], “there is an element of exaggeration in this theory of a difference between composition on a large and small scale, but the fact remains that in the Bagatelles we have some perfect and almost graphically vivid sketches of Beethoven in his changeable daily moods, tender or gently humorous one morning and full of fury, rude buffoonery or ill-temper the next. Not even his letters, in which we may find all these turns of mind too, reveal him more clearly than that.”

Beethoven thoroughly revised his Bagatelles op 33 shortly before publication. At the same time, however, he was incredibly busy and worked on his Piano Concerto No. 3, the Symphony No. 2 and the oratorio “Christ on the Mount of Olives.” In the light of Beethoven’s rising fame, he may have felt that he needed to satisfy a growing demand from students and amateurs for easy pieces from his pen.

We find a simple and innocent tune in No. 1, garnished with plenty of ornamentation and light-hearted transitions. No. 2 has the character of a scherzo that humorously manipulates rhythm and accents, while No. 3 appears folk-like in its melody and features a delicious change of key in the second phrase. The A-Major Bagatelle No. 4 is essentially a parody of a musette with a stationary bass pedal, and the minor-mode central section offers harmonic variety.

Beethoven provides some musical humour in No. 5 as this playful piece is a parody of dull passagework. In a really funny moment, the music gets stuck on a single note repeated over and over, like Beethoven can’t decide what to do next. In the end, he decides to repeat what he has already written before. In No. 6, we find a tune of conflicting characters, with the first phrase being lyrical and the second phrase being tuneful. The beginning of No. 7 almost suggests Beethoven’s Waldstein Sonata.

3 October 1882 Tymoszówka, Russian Empire 29 March 1937 Lausanne, Switzerland

Szymanowski’s early works show the influence of the late Romantic German school as well as the early works of Alexander Scriabin , as exemplified by his Étude Op. 4 No. 3 and his first two symphonies. Later, he developed an impressionistic and partially atonal style, represented by such works as the Third Symphony and his Violin Concerto n. 1 . His third period was influenced by the folk music of the Polish Górale people, including the ballet Harnasie, the Fourth Symphony, and his sets of Mazurkas for piano. King Roger , composed between 1918 and 1924, remains Szymanowski’s most popular opera

Alexander Scriabin

6 January 1872. Moscow – 27 April 1915 (aged 43) Moscow, Russia

Before 1903, Scriabin was greatly influenced by the music of Chopin and composed in a relatively tonal , late-Romantic idiom. Later, and independently of his influential contemporary Schoenberg , Scriabin developed a much more dissonant musical language that had transcended usual tonality but was not atonal, which accorded with his personal brand of metaphysics. Scriabin found significant appeal in the concept of Gesamtkunstwerk as well as synesthesia, and associated colours with the various harmonic tones of his scale, while his colour-coded circle of fifths was also inspired by theosophy . He is often considered the main Russian symbolist composer and a major representative of the Russian Silver Age.

Scriabin was an innovator and one of the most controversial composer-pianists of the early 20th century. No composer has had more scorn heaped on him or greater love bestowed.” Tolstoy described Scriabin’s music as “a sincere expression of genius.”Scriabin’s oeuvre exerted a salient influence on the music world over time, and inspired many composers, such as Nikolai Roslavets and Karol Szymanowski. But Scriabin’s importance in the Russian (subsequently Soviet) musical scene, and internationally, drastically declined after his death. “No one was more famous during their lifetime, and few were more quickly ignored after death.Nevertheless, his musical aesthetics have been reevaluated since the 1970s, and his ten published sonatas for piano and other works have been increasingly championed, garnering significant acclaim in recent years.

The main sources of Scriabin’s philosophy can be found in his notebooks, published posthumously. These writings are infamous for containing the declaration, “I am God.” This phrase, often wrongly attributed to a megalomaniac personality by those unfamiliar with mysticism, is in fact a declaration of extreme humility in both Eastern and Western mysticism. In these traditions, the individual ego is so fully eradicated that only God remains. Different traditions have used different terms (e.g., fana,samadhi) to refer to essentially the same state of consciousness. Although scholars contest Scriabin’s status as a theosophist, there is no denying that he was a mystic, especially influenced by a range of Russian mystics and spiritual thinkers, such as Solovyov and Berdyayev, both of whom Scriabin knew. The notion of All-Unity , the bedrock of Russian mysticism, is another contributing factor to Scriabin’s declaration “I am God”: if everything is interconnected and everything is God, then I, too, am God, as much as anything else.

Scriabin’s works reflect key cosmist themes: the importance of art, cosmos, monism, destination, and a common task for humanity. His music, embodying flight and space exploration themes, aligns with cosmist beliefs in humanity’s cosmic destiny. His philosophical ideas, particularly his declarations of being God and ideas about unity and multiplicity, should be understood within the mystical context of early Russian cosmism, emphasizing unity between man, God, and nature.