Listening to Magdalene Ho and Misha Kaploukhii playing four hands on one piano I am reminded of Rubinstein’s words ‘You cannot teach talent ………you are born with talent and you can only develop it ….you cannot learn talent.’

https://youtu.be/gex0sOR7XZ0?si=dRiFM4hftD-yCk6-

How right he was as I remember the first time I heard Magdalene competing for the Joan Chissell Schumann Prize at the Royal College. I was so overwhelmed by her playing of the 8th Novelette that whilst she was playing I wrote to her former teacher Patsy Toh ( Mrs Fou Tsong ), mesmerised by her sense of communication and self identification with the music. Fou Ts’ong was blessed with the same gift and his inspirational teaching has,like Guido Agosti, never been forgotten. Misha ,too, as a fresher his teacher Ian Jones, invited me to hear him play Rachmaninov First Concerto at Cadogan Hall. His mastery and self assurance were the seeds that four years on have given birth to one of the few pianists I could say would be capable of a modern day career. Misha has befriended Magdalene at the RCM where a reciprocal brother /sister relationship has been a two way inspiration for them both. Misha is now playing with more weight and searching musicianship whereas Magdalene has learnt that music can be a joy and inspiration when shared.

Just a few months ago Jed Distler , the renowned New York critic, composer and pianist, was staying in my house prior to the Chopin Competition which he was reporting on for Gramophone. I invited Magdalene and Misha over as Jed had been on the panel that had awarded Magdalene the Chappell Gold Medal ,and he too had been overwhelmed by her talent just as I had been a year earlier. He also awarded Misha , at the same time, the Hopkinson Smith Gold Medal .

Magdalene always a little shy at the dinner table suddenly sprang to life when Jed asked if anyone would play Shostakovich 9th, four hands with him. Thus began a musical evening of joy and brilliance.

Now we were all together around the piano – the chicken had been shared and we could get down to sharing music. It was on this occasion that Magdalene and Misha played together reading for the first time from the score the very Schubert that we heard today.

Each performance we heard today was like a great wave on which we were all carried along together. A dynamic drive and sense of communication, together with a feeling that we the audience were part of the act of discovery and creation too. A sense of informed improvisation where the notes spoke louder than words . The most extraordinary thing is that it never crossed my mind that this was four hands on one piano, such was the sense of unity with an instinctive sense of balance of mutual anticipation that created a real musical conversation.

Brahms of aristocratic nobility and Elgarian richness. There were cascades of beautiful arpeggios from Misha’s sensitive but authoritative hands as Magdalene delved deep into the soul of Brahms from below. A sumptuous outpouring of rhapsodic mellifluous playing of passionate intensity. Sounds of menace from Magdalene below with a deep pulsating bass with the improvised freedom of Misha with a melodic line lost in infinity. There was too a joyous outpouring of grandeur of glorious sumptuousness . The return of the ‘Angels’ at the end created a magic that reached even me on the other end of the line!

As Misha said, the Busoni deserves to be better known and they certainly gave a persuasive performance. From Magdalene’s bass folk melody elaborated together with busy exuberance. Capricious playfulness contrasted with long mellifluous outpourings with final bars in both of exhilarating excitement of festive frivolities.

Three of Brahms Chorale Preludes were played with an intense outpouring of weaving counterpoints as there was purity and nobility always with a glorious radiance of sound and unerring sense of balance of a united emotional commitment.

The Schubert burst onto the scene with dynamic drive but also with meticulous phrasing and sense of line. There were moments when Schubert’s divine inspiration drove these two players to heights that even they had not expected. As a knowing smile or a raised eyebrow were outwards signs that they too were listening with such sensitivity to every nuance or ravishing sound that Schubert could so miraculously compose in the last year of this short life.

The Rondo in A was played with a sense of enjoyment and ‘joie de vivre’ as they even shared a giggle or two.together over a momentarily dormant page turner. Daring to outdo each other with refined nuances of subtle beauty with a spontaneity where every note was unexpected but warmly welcomed as Magdalene reached to the top of the keyboard with a whispered vibration of a perfectly placed farewell .

We have heard some wonderful duo performances over the past few weeks including Dr Mather standing in for Viv Mclean’s indisposed partner. https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2025/11/11/zala-and-val-kravos-take-st-marys-perivale-by-storm-with-mastery-and-inspiration/

And who could forget the Kravos brother and sister team playing their entire duo programme without the score.

Or the Italian team of Bravi and Scapicchi or the mature mastery of Tessa Uys and Ben Shoeman. https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2025/09/02/tessa-uys-and-ben-shoeman-dreaming-of-elgar-in-the-pastoral-landscape-of-beethoven/

But today there was something rather special in the air with performances of a simplicity and mastery that as Rubinstein rightly said cannot be taught. It was a privilege to feel part of this sublime music making.

Misha Kaploukhii was born in 2002 and is an alumnus of the Moscow Gnessin College of Music. He is currently studying at the Royal College of Music and is an RCM and ABRSM award holder generously supported by the Robert Turnbull Piano Foundation and Talent Unlimited studying for a Master of Performance Diploma with Prof. Ian Jones. Misha has gained inspiration from lessons and masterclasses with musicians such as Claudio Martínez Mehner, Dmitri Bashkirov, Jerome Lowenthal and Konstantin Lifschitz. He has performed with orchestras around the world including his recent debut in Cadogan Hall performing Rachmaninov’s First Piano Concerto. His repertoire includes a wide range of solo and chamber music. Recent prizes include the RCM Concerto Competition, won in 2022 and 2025, the Hopkinson Gold Medal at the Chappell Medal Piano Competition, both the First and Audience Prizes in the UK Sheepdrove Piano Competition and Grand Prix at the Sicily International Piano Competition.

Malaysian pianist Magdalene Ho was born in 2003 and started learning the piano at the age of four. In 2013, she began studying in the UK with Patsy Toh, at the Purcell School. In 2015, she received the ABRSM Sheila Mossman Prize and Silver Award. As part of a prize won at the PIANALE piano festival in Fulda, Germany, she released an album of Bach and Messiaen works in 2019. She was a finalist at the Düsseldorf Schumann Competition 2023 and was awarded the Joan Chissell Schumann Prize for Piano at the Royal College of Music a few months later. In September 2023, she won the Clara Haskil International Piano Competition in Vevey along with receiving the Audience Prize, Young Critics’ Prize and Children’s Corner Prize. She has been studying with Dmitri Alexeev at the Royal College of Music since September 2022, where shee. is a Dasha Shenkman Scholar supported by the Gordon Calway Stone Scholarship, and by the Weir Award via the Keyboard Charitable Trust. She recently won the Chappell Gold Medal at the RCM. In 2025/26, she made her debut at the Tonhalle Zurich and with the Royal Scottish National Orchestra and the Lithuanian National Philharmonic Orchestra.

Franz Schubert 31 January 1797 – 19 November 1828 (aged 31) Vienna

The Allegro in A minor, D947 and the Rondo in A major, D951 were written in May and June 1828 respectively, and may well have been intended to form a two-movement sonata along the lines of Beethoven’s E minor Sonata Op 90. The A major Rondo was published in December 1828, less than a month after Schubert died.Schubert ‘s – Rondò in D major . D 608 has the title “Notre amitié est invariable” that could well apply to this rondò and indeed the young musicians who played today. Schubert left a large legacy of music for piano four-hands, extending as it does to some sixty works. Largely little known today, most were composed for domestic use at the ‘Schubertiads’ hosted by the composer’s Viennese friends.The passionate Allegro in A minor, written a month after the Fantasy in F minor , and sometimes known by its posthumous title ‘Lebensstürme’ gives a clear picture of Schubert’s inner life: of a man who wrote ‘Every night when I go to bed, I hope that I may never wake again, and every morning renews my grief.’ The Allegro in A Minor, Op. 144, demonstrates his mastery at writing for one piano, four hands. This large and passionate work was composed in 1828, the year of Schubert’s death. It is written in sonata-allegro form and may have been intended as the first movement of a sonata. It was first published by Anton Diabelli in 1840 with the title Lebensstürme: Characterischeres Allegro (Life’s Storms: Characteristic Allegro). The Allegro makes extensive use of chromaticism, Neapolitan sixth chords, and contrasts of moods.

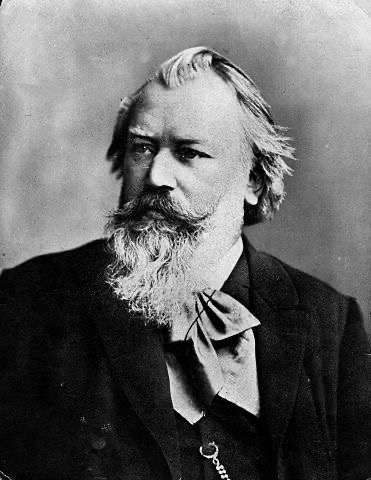

Johannes Brahms

7 May 1833 Hamburg 3 April 1897 (aged 63) Vienna

VARIATIONS ON A THEME OF ROBERT SCHUMANN FOR FOUR-HANDS, OP. 23

Published 1863. Dedicated to Miss Julie Schumann.

Theme. Leise und innig. Variation 1. L’istesso Tempo. Andante molto moderato. Variation 2 Variation 3 Variation 4 Variation 5. Poco più animato. Variation 6. Allegro non troppo. Variation 7. Con moto. L’istesso tempo. Variation 8. Poco più vivo. Variation 9. Variation 10. Molto moderato, alla marcia

Johannes Brahms twice chose a theme by his friend and mentor Robert Schumann as the basis for piano variations. While the Variations op. 9 were composed for piano solo, as an exception he wrote Opus 23 for a four-hand scoring. Its tender, chorale-like theme is particularly touching and was carefully chosen by Brahms: It was among Robert Schumann’s last musical thoughts, which the composer, already tormented by severe delusions, believed he heard from the voices of angels. The Variations, composed in 1861, end with a kind of funeral march and can be understood as a wistful farewell to his deceased friend.It is a misconception that Brahms wrote a great deal of original material for piano duet. He certainly produced skillful arrangements of his orchestral and chamber works for four hands on either one or two pianos, and the Hungarian Dances (by far his most familiar works without an opus number) are ever popular. But these variations are not only his first publication as an original work for piano duet, but also his only work with opus number that exists only in that form. The op. 39 Waltzes have two solo versions in addition to the duet version, and the versions of the Liebeslieder Waltzes (op 52 and op.65) for piano duet alone are rightly subordinate to the original with voices. . Like the earlier op.9 Schumann variation set for piano solo, this composition has deeply personal associations, not least the theme Brahms chose. Known as Schumann’s “last musical thought,” the composer sketched it in February 1854, saying that the E-flat melody was dictated to him by angels and apparently not realizing that it closely resembled the slow movement of his recently composed Violin Concerto. He began to write piano variations on the theme, right before his fateful jump into the Rhine on February 27. He finished the fifth of those variations the day after his rescue. The variations themselves remained unknown until they were published in 1939 (they have become known as the Geistervariationen or “Ghost Variations”). Clara Schumann considered the theme itself holy. When Brahms decided to write variations on it in 1861, Clara asked him not to reveal when the theme was composed given the stigma associated with her husband’s final years. Brahms himself finally published the original piano theme in 1893, but without Schumann’s five variations. Brahms’s own duet variations make the most of the four-hand medium. Each variation is highly distinct, and by the second, the melody of the theme is already abandoned. Thus, its return in the short coda is highly satisfying. He does stick closely to the structure and harmony throughout, including the repeated second part. He is also more adventurous with keys than in the contemporary (and much larger) Handel Variations for solo piano. Three of them are in three different minor keys (the “parallel,” the “mediant,” and the “relative” minor). Variation 5 is in the remote B major. He changes the 2/4 meter to 9/8 in Variation 5, 6/8 in Variation 7, and 4/4 for the last two. The set is a sort of celebration of and formal farewell to Schumann. Despite the funereal tone of Variation 4 and the more noble threnody of the last variation, there is never a sense of pure melancholy. The lower part, the secondo, comes into its own starting with Variation 2 and is truly exploited in the two “funereal” variations. There is much octave doubling between the hands of each part, but even this is not overdone. The dedication to the Schumann daughter Julie is interesting. She was 18 years old at the time, and it is possible Brahms had already taken a romantic interest in her. This grew over the next several years, but Brahms never declared himself, and Julie married an Italian count in 1869. While his infatuation was probably never more than that, her marriage contributed to a general sense of personal gloominess about his relationships and other things, which he channeled into the “Alto” Rhapsody,op.53 . Childbearing was taxing on the sickly and delicate Julie, and she died in 1872, earlier than any of her six siblings that survived childhood.

Eleven Chorale Preludes, Op. 122, is a collection of works for organ , written in 1896, at the end of the composer’s life, immediately after the death of his beloved friend, Clara Schumann, published posthumously in 1902. They are based on verses of nine Lutheran chorales , two of them set twice, and are relatively short, compact miniatures. They were the last compositions Brahms ever wrote, composed around the time that he became aware of the cancer that would ultimately prove fatal; thus the final piece is, appropriately enough, a second setting of “O Welt, ich muß dich lassen. Six of them were transcribed for piano 4/5 8-11 by Busoni in 1902 arranges for four hands by Eusebius Mandyczewski

‘Finnländische Volksweisen’ [Finnish Folksongs] Op.27 for piano duet. Andante molto espressivo – allegretto moderato – presto 2. Andantino – tranquillo – vivace – presto

Ferrucio Busoni – pianist, composer, arranger, educator, philosopher – was born in 1866 and died a hundred years ago in 1924, making this an anniversary year. These pieces date from the late 1880s, when the composer had a post teaching the piano in Finnland. The folksongs themselves – there are six of them, three in each movement – and the manner in which Busoni employs them is far from simple: among the devices used are reharmonisations and other forms of variation, motivic and canonic reworkings, unusual textures and dramatic transitions. The idea, then, is to create a kind of tone poem in two movements and Busoni achieves an almost symphonic character in his realisation. Bartok and Kodaly (Vaughan-Williams in England) are generally considered to be pioneers in the use of folk materials in art music but Busoni is ahead of the curve here, even if this composition owes something to the potpourri tradition .