Misha Kaploukhii at St James’s Piccadilly with the stylistic beauty and refined brilliance of Clementi and the supreme fantasy world of Schumann’s magical Davidsbündler .

The crowning glory must go to Liszt’s monumental Norma Fantasy played with fearless abandon and breathtaking beauty. The wonderful thing about actually being in this beautiful church is for the acoustic where usually notey briliiance is transformed into streams of wonderful sounds . Here was a whole orchestra for Liszt’s operatic fantasy and a refined tonal palette for Clementi. Heartrending beauty for the initimate dream world of Eusebius and the impish good humour of Florestan.

I doubt that Schumann’s midnight chimes have even been struck so poignantly ‘ as quite superfluously Eusebius remarked as follows: but all the time great bliss spoke from his eyes.”

Opening with Clementi he made us all fall in love instantly with this much neglected composer, so often used as torture for aspiring young pianists. Clementi was not only a superb technician with playing and constructing pianos, but he was also a master composer as Misha revealed today. Misha unraveled the secrets behind the notes with an ‘Allegro’ that was truly ‘con espressione.’ From the first notes, lovingly shaped with a refined tonal palette that could reveal a sense of longing and nostalgia within the very sounds that resounded around this most beautiful of churches. Subtle phrasing of great delicacy and poignant beauty. It was the same beauty that he brought to the haunting ‘Lento e patetico’ with a cantabile of weight where the searing intensity of the melodic line was shared with the extraordinary web of accompaniment. An expressiveness that was of sublime simplicity and that from Misha’s sensitive hands could speak with rare beauty and intensity. There was a scintillating brilliance to the ‘Presto’ ,but even here he brought an extraordinary shape and colour to the Mendelssohnian streams of notes. There were ornaments that sprang from his well oiled fingers like springs glistening in this perpetuum mobile of silvery sounds. A beguiling ‘joie de vivre’ of infectious rhythmic elan but always of such rich fantasy and expressive intensity.

Clementi wrote over 100 Sonatas and if this is an example ,as Misha showed us today, please play on and on !

Davidsbündler is one of Schumann’s most beautiful creations and found in Misha an ideal interpreter, creating a sound world that I have rarely experienced in the concert hall. This was a memorable experience where beauty and brilliance were always balanced with poetic intensity and ravishing sounds. A technical mastery that one was not aware of, such was the musical meaning he gave to even the most treacherous passages. The opening was played with a clarity that showed his mastery of the pedal and allowed him to find a beguiling insinuating opening where joy and sorrow are truly mingled. Tenderness and expressiveness mixed with impish good humour and passion. All played with a subtle freedom that sounded almost like an improvisation, as the music must have been when it was still wet on the page. All this was revealed in the first six of these eighteen tone poems. Technical mastery too as the cross rhythms of the sixth passed unnoticed as they just added to the poetic intensity. The seventh was a true reawakening as it slowly took wing with the intensity of the poetic weight that Misha infused into these simple notes. Fleeting lightness , ‘Frisch ‘ indeed, as it burst into a passionate discourse as: ‘Florestan’s lips quivered painfully ‘. There was Brahmsian grandeur too, as the ‘ballade’ of number ten filled every corner of the church with sumptuous full sounds to be experienced again in ‘Wild und lustig’ ,magically dissolving into a chorale of subtle Philadelphian orchestral richness. One of Schumann’s most beautiful creations is the fourteenth and Misha played it with a wonderful sense of balance that allowed the melodic line to pass so simply from one voice to another with even the accompaniment allowed to weave its magic spell. Answered by imperious interruptions and searing romantic intensity before the fidgety meanderings of chattering voices that are interrupted by a magical change of key over a single F sharp. ‘As if from a distance’ we were treated to a vision of loveliness that with this misty acoustic and Misha poetic imagination held us spell bound as we were surrounded by such beauty. Coming to an end only to be reawakened from B minor suddenly to find ourselves in a whispered C major and a ‘Valse de l’adieu’ with twelve chimes in the bass as this dream dissolves ‘as such bliss could be seen in Eusebius’s eyes.’

Such poetic utterances and a performance that I have rarely heard played with such beauty and understanding as today. Something to truly cherish and as Mitsuko Uchida says will grow ever more beautiful in one’s mind as time passes and one relives such a magic moment.

Liszt’s mighty Norma Fantasy opened with dramatic gestures as Misha had now entered the world of Grand Opera,with its rhetorical outpouring of heart rending beauty and breathtaking virtuosity. Liszt could condense this opera into just fifteen minutes and show us every detail of the opera, even correcting the order in which Bellini had written the arias. Misha brought the breathing of a Callas to the great operatic arias that unfolded with such mastery from Misha’s hands. Octaves that were played with the ease that most would play single notes. But these were not just octaves they were waves of sound that took us into realms of the three handed mastery that Liszt and Thalberg could reveal on a piano that now had a ‘soul’ .What wonders there were as Misha struck the timpani with such beguiling insinuation. ‘Arpeggiandi con grandezza’ I have never heard played with such ease as the melodic line was embellished by the devil himself. Breathtaking is the only way one could describe the ‘Presto con Furia’ with a technical mastery that was phenomenal .A relentless drive that I have only heard once before in the concert hall and that was from Gilels in the Spanish Rhapsody. The thrill of live performance is the thrill of the circus entertainer as we sit on the edge of our seats enthralled as we wonder whether he will fall off the high wire or get to the other side triumphantly in one piece !

A quite memorable recital from a pianist who the world awaits with baited breath.

He has recently completed his undergraduate studies at the Royal College of Music and is an ABRSM award holder generously supported by the Eileen Rowe Trust, Talent Unlimited Charity, The Keyboard Charitable Trust and The Robert Turnbull Foundation. He was a Drake Calleja Trust scholar, 2023/4 and is now studying for a Master of Performance with Professor Ian Jones.

Misha is thrilled to be chosen as one of the recipients of the prestigious LSO Conservatoire Scholarships, 2024/5 which will include support and professional development along with coaching and performance opportunities. His recent prizes include RCM Concerto Competition, International Ettlingen Piano Competition, Hopkinson Gold Medal at the Chappell Medal Competition and the 1st and Audience prizes at the 2024 Sheepdrove Piano Competition.

Misha has gained inspiration from lessons and masterclasses with musicians such as Claudio Martínez Mehner, Dmitri Bashkirov, Jerome Lowenthal, Dinara Klinton, Konstantin Lifschitz, Dame Imogen Cooper. He was a participant at the Oxford Piano Festival in 2024, where he was coached by Stephen Kovacevich, Barry Douglas and Kathryn Stott.

His performances with orchestras in UK include debuts in Cadogan Hall playing Rachmaninov’s 1st Concerto with YMSO and James Blair, Liszt’s 2nd Concerto with RCM Symphony orchestra with Adrian Partington and very recently, Rachmaninov’s 4th Concerto performed with the Albion Orchestra.

He has performed in the UK, Italy and France at the venues including St Mary’s Perivale, Razumovsky Recital Hall, Leighton House, Sala dei Notari and Giardini La Mortella with a wide range of solo and chamber repertoire. In 2023 Misha was invited to play Rachmaninoff Symphonic Dances arranged for solo piano at the prestigious Budleigh Literary Festival as a part of Fiona Maddocks conversation about her book “Rachmaninoff in Exile”.

He gave recitals for William Walton Foundation in Ischia and recently was invited to play Young Master recital and a chamber recital with the soloists of Umbria Ensemble at the Perugia Music Festival.

Misha’s engagements have included solo recitals in Razumovsky Recital Hall, St Mary Le Strand, 1901 Arts Club, British Institute in Florence and Steinway Hall in Milan. He has performed Chopin F minor Concerto in the National Liberal Club and Brahms 2nd Piano Concerto in Cadogan Hall with James Blair.

Presented in association with Talent Unlimited

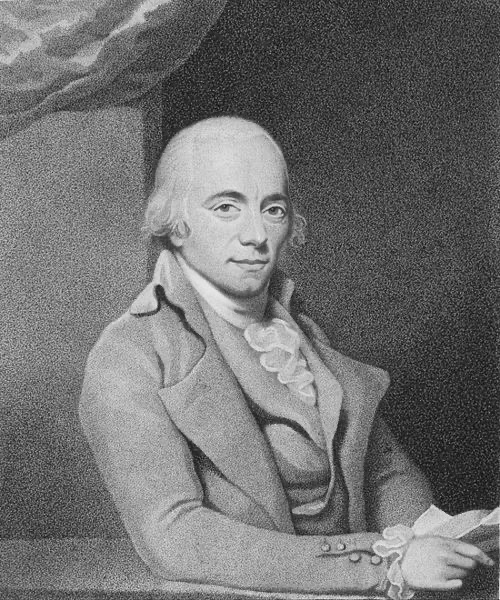

23 January 1752 Rome – 10 March 1832 Evesham , Worcestershire, England

Muzio Filippo Vincenzo Francesco Saverio Clementi (23 January 1752 – 10 March 1832) was an Italian and British composer,virtuopso pianist ,pedagogue ,conductor, music publisher, editor, and piano manufacturer who was mostly active in England. Encouraged to study music by his father, he was sponsored as a young composer by Sir Peter Beckford, who took him to England to advance his studies. Later, he toured Europe numerous times from his long-standing base in London. It was on one of these occasions, in 1781, that he engaged in a piano competition with Mozart. As a composer of classical piano sonatas, Clementi was among the first to create keyboard works expressly for the capabilities of the piano. He has been called “Father of the Piano”. Clementi composed almost 110 piano sonatas . Some of the earlier and easier ones were later classified as sonatinas after the success of his Sonatinas Op. 36.

Of Clementi’s playing in his youth, Moscheles wrote that it was “marked by a most beautiful legato, a supple touch in lively passages, and a most unfailing technique.” Mozart may be said to have closed the old—and Clementi to have founded the newer—school of technique on the piano.

The F sharp minor Sonata—usually identified as Op 26 No 2 but in fact published originally by Dale of London as the fifth of ‘Six Sonatas for the Piano Forte; dedicated to Mrs Meyrick … Opera 25’ (entered Stationers’ Hall, 8 June 1790)—is an example of what Shedlock in 1895 defined as that class of Clementi work where ‘his heart and soul were engaged’ to the full. The tenor of its first movement is a mixture of dolce expression, capricious fingerwork, off-beat sforzando accents, teasing articulation (the slurs and dots tell in an orchestral way), and tonal surprise The middle slow movement is in B minor, a poignantly felt song, potently textured and voiced, dramatic in its contrasts of soft and loud, of minorial pathos and sweet maggiore release, of dark diminished-seventh tension, of poetically meaningful ornamentation. The 3/8 Presto finale is an imaginatively inventive cameo of Scarlattian brilliance and Mendelssohnian fleetness, of glittering thirds and equally elfin and stormy octaves. Historically, such music is Classical. Temperamentally, it is Romantic.

Franz Liszt 22 October 1811 Doborján, Austrian Empire. 31 July 1886 (aged 74)Bayreuth

During the 1800s opera had a lot of appeal to audiences. From big dramatic storylines to emotional arias, opera was in its prime during this century. Although opera was perceived to have a glamorous aura, it was actually quite inaccessible for a large part of the public due to price and cultural differences. Therefore it is not surprising that many pianists sought to gain more audiences by composing, arranging and performing their own operatic fantasies.

Franz Liszt’s career gained proper traction after he started performing his bravura transcriptions. These were ideal outlets for pianists to show off their virtuosity and prowess over the instrument. On the other hand, they were also ideal for audiences as they were able to access those iconic operatic melodies, just in a slightly smaller and diluted format.Liszt undertook the challenge of diluting Bellini’s opera Norma into a 15 minute solo piano work in 1841. The work easily equals the dramatic impact of the original opera through Liszt’s dynamic and highly virtuosic writing. No less than seven arias dominate Liszt’s transcription of Norma which are threaded together to create a nearly continuous stream of music.

The title role of Norma is often said to be one of the hardest roles for a soprano to sing, and this adds to the drama and intensity of the music. A brief summary of the opera :

“Norma, a priestess facing battle against the Romans, secretly falls in love with a Roman commander, and together they have two illegitimate children. When he falls for another woman, she reveals the children to her people and accepts the penalty of death. The closing scenes and much of the concert fantasy reveal Norma begging her father to take care of the children and her lover admitting he was wrong.”The complex music represents the tragedy woven into this story, which is perhaps why Liszt made the effort to transfer the challenges of this score into a piano fantasy. With cascading arpeggios, massive interval changes and dynamic changes at every turn, Réminiscenes is a true test of technical ability. The score is saturated with huge chordal movement, fast-paced cadenza sequences and a raffle of different tempo markings.

As the Liszt expert Leslie Howard states : ‘The Norma Fantasy stands next to that on Don Giovanni for its ability to capture the essence of the operatic drama in a new structure. It is probably for dramatic reasons that Liszt ignored the famous aria ‘Casta Diva’ (which Thalberg used as the basis for his fantasy) but instead chose no fewer than seven other themes for his gloriously elaborate work—a triumph of understanding not just of Bellini’s masterpiece, but of practically all the sound possibilities of the piano in Romantic literature.’

Born 8 June 1810 Zwickau ,Saxony Died 29 July 1856 (aged 46) Bonn

Robert Schumann’s early piano works were substantially influenced by his relationship with Clara Wieck . On September 5, 1839, Schumann wrote to his former professor: “She was practically my sole motivation for writing the Davidsbündlertänze, the Concerto, the Sonata and the Novelettes .” They are an expression of his passionate love, anxieties, longings, visions, dreams and fantasies.

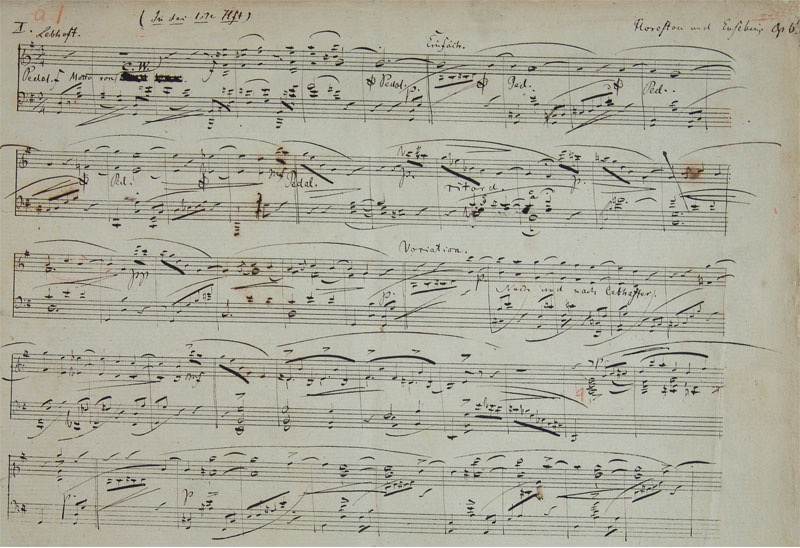

The theme of the Davidsbündlertänze is based on a mazurka by Clara Wieck. The intimate character pieces are his most personal work. In 1838, Schumann told Clara that the Dances contained “many wedding thoughts” and that “the story is an entire Polterabend (German wedding eve party, during which old crockery is smashed to bring good luck)”.

The pieces are not true dances , but characteristic pieces, musical dialogues about contemporary music between Schumann’s characters Florestan and Eusebius. These respectively represent the impetuous and the lyrical, poetic sides of Schumann’s nature. Each piece is ascribed to one or both of them. Their names follow the first piece and the appropriate initial or initials follow each of the others except the sixteenth (which leads directly into the seventeenth, the ascription for which applies to both) and the ninth and eighteenth, which are respectively preceded by the following remarks: “Here Florestan made an end, and his lips quivered painfully”, and “Quite superfluously Eusebius remarked as follows: but all the time great bliss spoke from his eyes.” In the second edition of the work, Schumann removed these ascriptions and remarks and the Tänze from the title, as well as making various alterations, including the addition of some repeats. The first edition is generally favored, though some readings from the second are often used. The suite ends with the striking of twelve low Cs to signify the coming of midnight. The first edition is preceded by the following epigraph:

Alter Spruch

In all und jeder Zeit

Verknüpft sich Lust und Leid:

Bleibt fromm in Lust und seid

Dem Leid mit Mut bereit

Old saying

In each and every age

joy and sorrow are mingled:

Remain pious in joy,

and be ready for sorrow with courage.

There are 18 sequences :

- Lebhaft: Lively (Vivace), G major, Florestan and Eusebius;

- Innig: Intimately (Con intimo sentimento), B minor, Eusebius;

- Etwas hahnbüchen: Somewhat clumsily (Un poco impetuoso) (1st edition), Mit Humor: With humor (Con umore) (2nd edition), G major, Florestan (hahnbüchen, now usually hanenbüchen or hagebüchen, is an untranslatable colloquialism roughly meaning “coarse” or “clumsy”. Ernest Hutchinson translated it as “cockeyed” in his book The Literature of the Piano.);

- Ungeduldig: Impatiently (Con impazienza), B minor, Florestan;

- Einfach: Simply (Semplice), D major, Eusebius;

- Sehr rasch und in sich hinein: Very quickly and inwardly (Molto vivo, con intimo fervore) (1st edition), Sehr rasch: Very quickly (Molto vivo) (2nd edition), D minor, Florestan;

- Nicht schnell mit äußerst starker Empfindung: Not fast, with very great feeling (Non presto profondamente espressivo) (1st edition), Nicht schnell: Not fast (Non presto) (2nd edition), G minor, Eusebius;

- Frisch: Freshly (Con freschezza), C minor, Florestan;

- No tempo indication (metronome mark of ♩ = 126) (1st edition), Lebhaft: Lively (Vivace) (2nd edition), C major, Florestan;

- Balladenmäßig sehr rasch: Balladically very fast (Alla ballata molto vivo) (1st edition), (“Sehr” and “Molto” capitalized in 2nd edition), D minor (ends major), Florestan;

- Einfach: Simply (Semplice), B minor–D major, Eusebius;

- Mit Humor: With humor (Con umore), B minor–E minor and major, Florestan;

- Wild und lustig: Wildly and merrily (Selvaggio e gaio), B minor and major, Florestan and Eusebius;

- Zart und singend: Tenderly and singing (Dolce e cantando), E♭ major, Eusebius;

- Frisch: Freshly (Con freschezza), B♭ major – Etwas bewegter: With agitation (poco piu mosso), E♭ major with a return to the opening section (with the option to go round the piece once more), Florestan and Eusebius;

- Mit gutem Humor: With good humor (Con buon umore) (in 2nd edition, “Con umore”), G major – Etwas langsamer: A little slower (Un poco più lento), B minor; leading without a break into

- Wie aus der Ferne: As if from afar (Come da lontano), B major and minor (including a full reprise of No. 2), Florestan and Eusebius; and finally,

- Nicht schnell: Not fast (Non presto), C major, Eusebius.