“Music has the power to bring people together, no matter race, gender, sex, or religion, and it creates emotions unable to be felt in everyday life. It is important to me because it gives my life a new flavour, a new colour, and a new spectrum.” Shunta Morimoto aged 14.

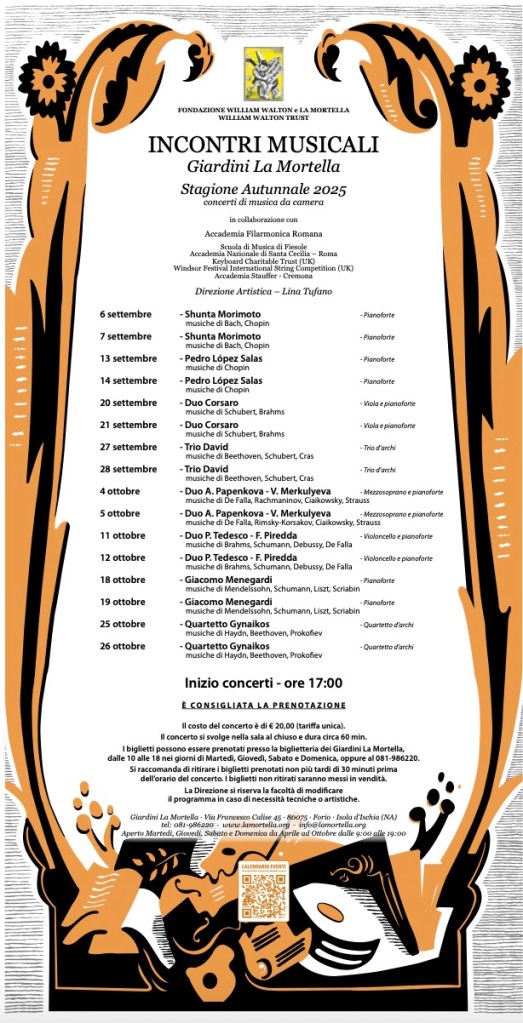

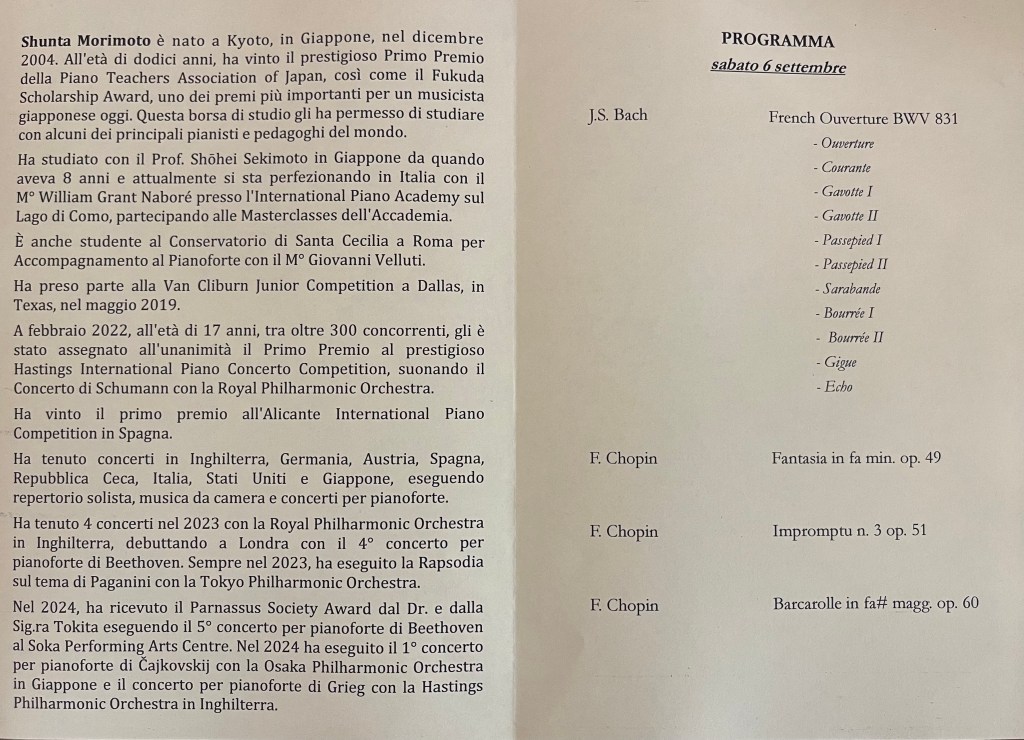

Shunta Morimoto just arrived from Japan to play at La Mortella before concerts in Ireland and London, at the beginning of what will be a very busy season for this twenty year old pianist. Unanimous winner of Hastings International Piano Competition when he was seventeen, and now embarking on a career that has already taken him to Los Angeles to play Brahms 2 having played Beethoven 4 and Liszt 1 with the RPO in England, and when he was only sixteen Rachmaninov 3 with the Tokyo Philharmonic.

https://youtu.be/beUHzao-ZXw?si=3VnixlgUlEftm3G6

A rising star indeed with an insatiable appetite to discover ever more about the mysteries that are hidden within the scores. A quite extraordinary artist that Stanislaw Ioudentich ( winner of Van Cliburn in 2001 and distinguished teacher in Oberlin ,Como and Madrid ) declared quite candidly ‘ is the greatest talent I have ever known.’

https://youtu.be/wLOeKop2-AA?si=VYA6–NdWwGGNYgF ) https://youtu.be/8wJlO0l2BxM?si=jeCmQIH9wBYnVpYY

Here is Shunta aged fourteen in Fort Worth – Van Cliburn. ” Shunta Morimoto has won first in his category three times in the Piano Teachers’ National Association of Japan Piano Competition, as well as other competitions in his home country, which has led to multiple performances in Tokyo, Yokohama, and his home town of Kyoto. He also placed first in the 2018 Aloha International Piano Competition and subsequently gave concerts in Hawaii, including with the Hawaii Youth Symphony. He says that experience helped him believe in the “magical power of music,” because he could use it to communicate easily where a language barrier may have prohibited him. A student at Momoyama Junior High School, Shunta currently studies with Shohei Sekimoto.”

Shunta has a hand that has been moulded by superb teaching in Japan from a very early age, giving him a flexibility and true weight that never attacks the key but sucks the life blood from each one with beautiful natural horizontal movements , it is like watching a painter in front of his canvas. Delving deep into the scores having been mentored by William Naboré in Rome and Como for the past five years, he has an insatiable appetite to acquire knowledge and share inspiration as he tries to find the true meaning behind the notes bequeathed to posterity by the great composers.

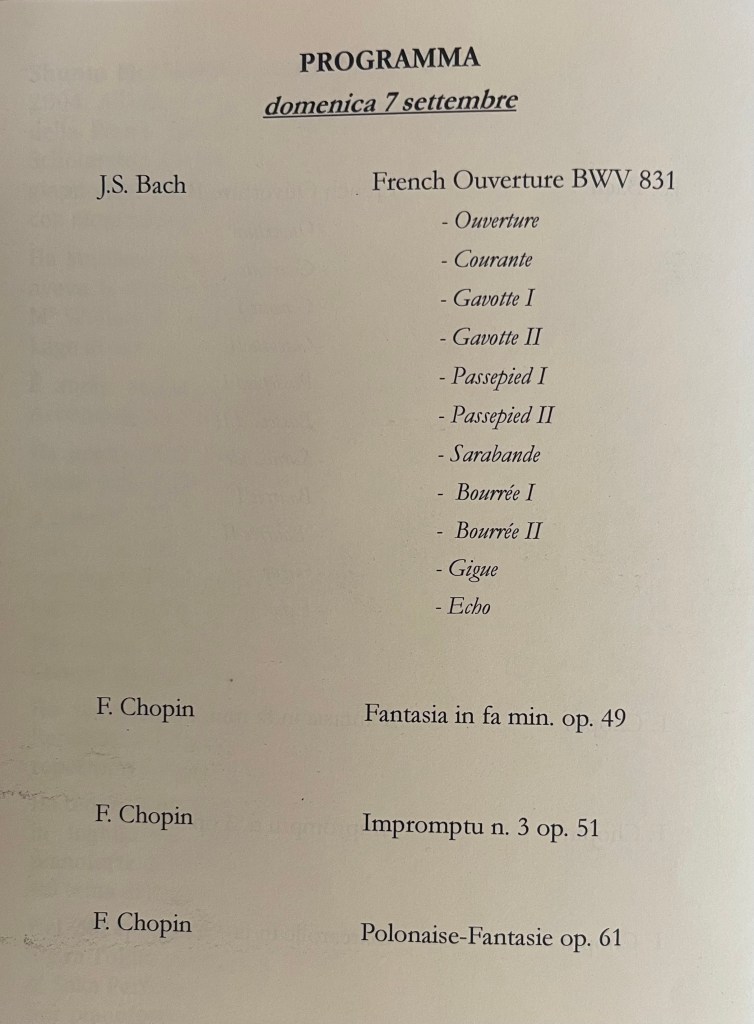

And it was the Great French Overture by Bach that opened Shunta’s two recitals in Ischia. Often known as the seventh Partita, it is a work of great significance and appears on programmes of only the most eclectic musicians such as Andras Schiff or Angela Hewitt. In eleven movements lasting over thirty minutes it opens with an Overture of monumental proportions. Shunta played with commanding authority as the opening flourish immediately held our attention with its nobility and grandeur. Subtle ornaments unwound like springs from his fingers never interfering with the overall outline. It was like a great Gothic Cathedral taking our breath away as we are overwhelmed by such a man made construction. Bursting into life in a spectacular rhythmic way with energy that came from within the notes with a buoyancy and elan of extraordinary eloquence. The genius of Bach bringing back the opening with an ever more poignant nobility. There was a delicacy to the meanderings of the ‘Courante’ and a deliberate fluidity to the ‘Gavottes’ and a decisive brilliance to the ‘Passepieds’. Shunta brought a subtle veiled beauty to the ‘Sarabande’ contrasting with the boisterous dance of the ‘Bourées’. A ‘Gigue’ that just flew from his fingers, but it was above all the ‘Echo’ that Shunta played with impish good humour and enticing rhythmic characterisation. A ‘tour de force’ of concentration and intellectual understanding of a maturity, way beyond Shunta’s twenty years.

It was followed by some of the greatest works by Chopin. Truly masterpieces that the genius of Chopin had created for a piano that had evolved from the earlier keyboard instruments, that now had a sustaining pedal that became the very soul of the piano – to quote Anton Rubinstein. It becomes a full orchestra capable of a variety of sounds where above all Chopin could create new art forms of refined elegance and fantasy. It was this full orchestra that Shunta showed us today choosing Chopin’s only two Fantasies that are art forms that do not conform to the standard practice of the day.Following in Schubert’s footsteps trying to find a form that had logic and cohesion but also the character of operatic proportions where there is a wondrous story to tell. No longer tied down with formal tradition but able to bring a personal spirit to the music as the Romantic era broke away from the formal constraints of the baroque period.

Shunta played the Fantasy with expansive beauty, nobility and delicacy. The opening was like a sunrise with the unfolding of the drama about to explode. A passionate outpouring of extraordinary mastery and a remarkable palette of colours. An unusually long wait before the opening of the central episode that was of extraordinary poignancy. A vision of paradise was opening up with startling simplicity and purity. The passionate return of the opening was played with even more burning intensity disintegrating to a beseeching cadenza with its simple whispered beauty. It was interesting to note the keys that Shunta held silently in the bass to allow the harmonics to reverberate without the cloud of pedal. It was greeted by a miraculous wave of sounds to the final imperious closing chords.

The G flat Impromptu was played with a beguiling beauty of aristocratic good taste. Shunta added another level of fantasy to this work with an extraordinary range of subtle colouring and shaping of the phrases. The gentle whispered return of the opening, after the ravishing noble beauty of the tenor voice of the central episode, I will cherish for a long time. I have always Rubinstein in my ears when I hear this work as he played it with that same aristocratic French heart that he brought to his friend Poulenc’s music. Shunta showed me another side today with a dream like fantasy world of glistening beauty, without loosing any of the refined elegance that is so extraordinary in this wondrous Impromptu.https://youtu.be/mB9MgedVR3o

It was the same magic that he brought to the Barcarolle op 60 which is one of Chopin’s greatest creations. It is a true ‘Lied von der Erde’, starting from the deep bass C sharp that just opens up the piano so that all that follows can float on the continuous gentle wave of the lagoon, creating pure magic. A magic land indeed of a story told with refined beauty but also with passion. Barely touching the keys in the miraculous bel canto central episode as he allowed the music to gradually engulf him as the temperature rose. The extraordinary thing about Shunta’s playing is the depth of sound that is never ungrateful or percussive but comes from deep within the very soul of the music.There was a refined beauty to the final meanderings as we near the sad farewell , with the gentle tenor melody just glowing in the distance.This was a passage that Ravel, the absolute master of colour, so admired. A cascade of notes leading to the final simple vision to this wondrous land of dreams.

Two encores showed off the wonderful jeux perlé and also the beguiling sense of showmanship that is so much part of the Waltzes of Chopin. Op 42 with its intricate knotty rhythms was played with an extraordinary sense of dance and freedom . https://youtu.be/QTebZVST-oM?si=sipmtOeJ3v0EuXrr

The Prelude op 28 n. 3 just flowed from Shunta’s fingers with disarming simplicity as this extraordinary jewel in a crown of 24 problems ( according to Fou Ts’ong) was shaped as the miniature tone poems of each one should be, and that Shunta will treat us to in the National Liberal club in London for halloween .

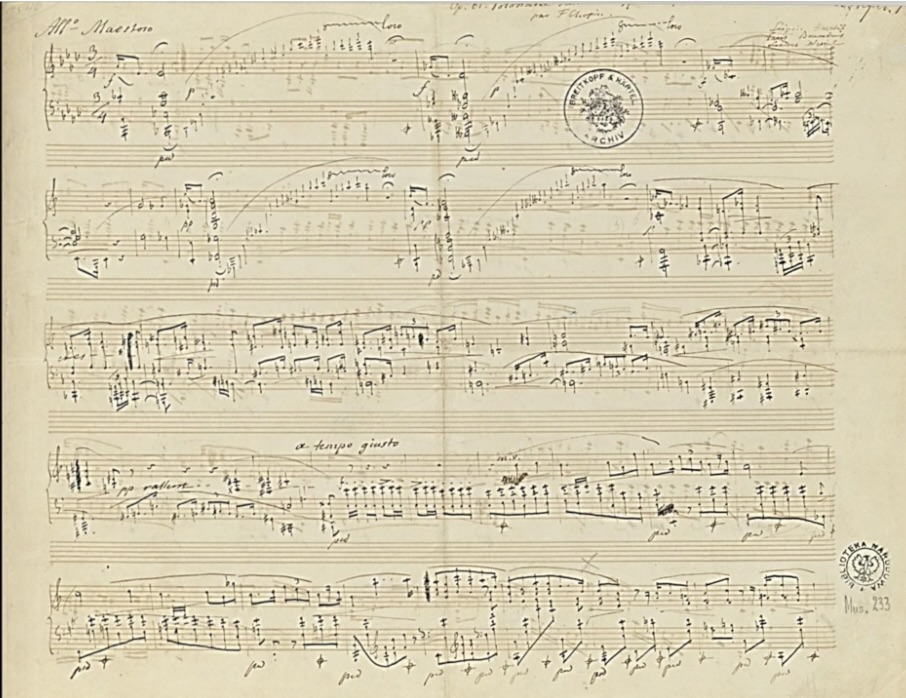

The second recital was with the addition of the Polonaise- Fantaisie op 61 ,the twin of the Barcarolle op 60. Fantasy was the word for the first chords just opening up a magic world of wondrous whispered sounds. Playing these ‘vibrations’ with one single movement it became truly an undulation of the senses both visual and audial. A Polonaise that burst onto the scene with unusual vehemence and that Shunta played with passionate drive, but there was also a feeling of tenderness and wonder. A beautifully free,almost improvised, central episode where the melodic line passed from the tenor to the soprano register with poetic beauty and tranquility .Gradually trills appeared magically vibrating with ever more intensity until the opening chords return with even more etherial vibrations. Suddenly the intensity increases as Chopin reaches for a climax of exhilaration and nobility played by Shunta with extraordinary power and passion. Octaves flying as the tension diminishes and this fantasy world of genial creation comes to a close on a single isolated A flat.

Shunta added to his encore of op 42 that he had played yesterday too, with a magical account of Chopin’s Berceuse.Whispered tones made us listen even more intently to the beauty of the magic web of variations that Chopin could weave,adding to the most beautiful of all lullabies with a rocking motion of sumptuous innocence and beauty.

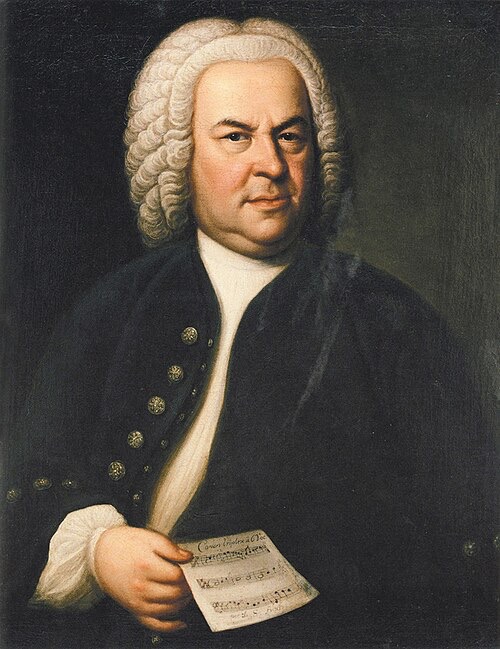

of the canon BWV 1076

Born 21 March 1685 Eisenach Died. 28 July 1750 (aged 65) Leipzig

The Overture in the French style, BWV 831, original title Ouvertüre nach Französischer Art, also known as the French Overture and published as the second half of the Clavier Übung II in 1735 (paired with the Italian Concerto ), is a suite in B minor for a two-manual harpsichord.

Movements: Ouverture. Courante. Gavotte I/II. Passepied I/II

Sarabande. Bourrée I/II. Gigue. Echo

The term overture refers to the fact that this suite starts with an overture movement, and was a common generic name for French suites (his orchestral suites were similarly named). This “overture” movement replaces the allemande found in Bach’s other keyboard suites. Also, there are optional dance movements both before and after the Sarabande. In Bach’s work optional movements usually occur only after the sarabande. All three of the optional dance movements are presented in pairs, with the first one repeated after the second, but without the internal repeats. Also unusual for Bach is the inclusion of an extra movement after the Gigue, the “Echo,” a piece meant to exploit the terraced loud and soft dynamics of the two-manual harpsichord. Other movements also have dynamic indications (piano and forte ), which are not often found in keyboard suites of the Baroque period, and indicate here the use of the two keyboards of the harpsichord. With eleven movements, the French Overture is the longest keyboard suite ever composed by Bach. It usually has a duration of around 30 minutes if all the repeats in every movement are taken.

Bach wrote an earlier version of the work, in the key of C minor (BWV 831a) later transposed to B minor to complete the cycle of tonalities in Parts One and Two of the Clavier-Übung.The keys of the six Partitas (B♭ major, C minor, A minor, D major, G major, E minor) of Clavier-Übung I form a sequence of intervals going up and then down by increasing amounts: a second up (B♭ to C), a third down (C to A), a fourth up (A to D), a fifth down (D to G), and finally a sixth up (G to E).[1] The key sequence is continued in Clavier-Übung II (1735) with two larger works: the Italian Concerto, a seventh down (E to F), and the French Overture, an augmented fourth up (F to B♮). Thus a sequence of customary tonalities for 18th-century keyboard compositions is complete, beginning with the first letter of Bach’s name (B♭, in German is B) and ending with the last (B♮ in German is H).

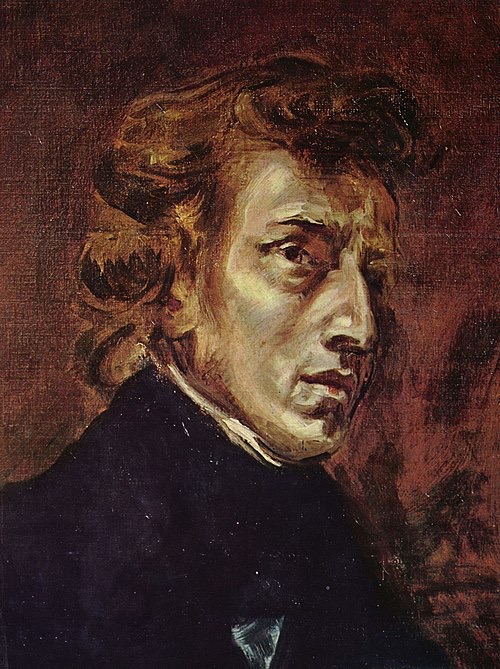

Fryderyk Franciszek Chopin. 1 March 1810. Żelazowa Wola, Duchy of Warsaw. 17 October 1849 (aged 39) Paris. Chopin, 28, at piano, from Delacroix’s 1838 joint portrait of Chopin and Sand

The Polonaise-Fantaisie in A flat op 61, was dedicated to Mme A. Veyret, written and published in 1846.This work was slow to gain favour with musicians, due to its harmonic complexity and intricate form . Arthur Hedley was one of the first critics to speak positively of the work, writing in 1947 that it “works on the hearer’s imagination with a power of suggestion equaled only by the F minor Fantasy ore the Fourth Ballade ” . It is intimately indebted to the polonaise for its metre, much of its rhythm , and some of its melodic character, but the fantaisie is the operative formal paradigm, and Chopin is said to have referred initially to the piece only as a Fantasy. Parallels with the Fantaisie in F minor include the work’s overall tonality, A-flat, the key of its slower middle section, B major, and the motive of the descending fourth.

The Barcarolle in F sharp major op 60 composed between autumn of 1845 and summer 1846, three years before his death.[1]

Based on the barcarolle rhythm and mood, it features a sweepingly romantic and slightly wistful tone. Many of the technical figures for the right hand are thirds and sixths, while the left features very long reaches over an octave. Its middle section is in A major , and this section’s second theme is recapitulated near the piece’s end in F-sharp. It is also one of the pieces where Chopin’s affinity to the bel canto operatic style is most apparent, as the double notes in the right hand along with spare arpeggiated accompaniment in the left hand explicitly imitates the style of the great arias and scenas from the bel canto operatic repertoire. The writing for the right hand becomes increasingly florid as multiple lines spin filigree and ornamentation around each other.

This is one of Chopin’s last major compositions, along with the Polonaise – Fantasie op 61 is often considered to be one of his more demanding compositions, both in execution and interpretation.

The F minor Fantasy is an expansively constructed work belonging to the sphere of such epic-dramatic genres in the Chopin oeuvre as the ballades and the scherzos. Yet it occupies a distinctive, exceptional place among them. Discounting the rather trivial fantasies of the potpourri type written to operatic or other themes, such as were fashionable in Chopin’s day, we immediately perceive his Fantasy as a work referring to the most splendid and most ambitious traditions of the piano fantasies of Mozart and the Wanderer-Fantasie of Schubert . From Chopin’s letters, we also know that he employed the name ‘fantasy’ to describe works that broke with the canon of unambiguously defined genres (e.g. the Polonaise – Fantaisie ). The term ‘fantasy’ unquestionably implies some sort of freedom from artistic rules and a peculiar, Romantic expression. It was completed and published in 1841. Through its narrative it insistently draws the listener into an expansive musical tale. But can we answer the question as to what this tale is about? In the interpretations of many commentators we find the conviction that Chopin’s work might be an echo of improvisations on national themes (as is indicated by some of the Fantasy’s melodic strands). So Fantasy would contain a distinctive patriotic message, leading from the elegiac tone at the beginning of the work to the triumphant accents in its closing climax.

In the construction of this fascinating composition, we find elements of various forms (e.g. sonata form combined with the principle of cyclical form), yet defining the form of the Fantasy is no easy task, even though the work does display a rigorous logic of construction. We find here moments that are very precisely formed (particular themes) and others of a looser character, akin to improvisation (especially the figural passages). In general terms, the flow of the work may be presented as follows: an introduction with two ‘march’ themes, a sort of exposition of the rich thematic material, a middle section (lyrical, at a slow tempo, in the key of B major), a sort of reprise and a coda (a reminiscence of the middle section). Of course, there are other possible interpretations of this work, which represents a real challenge for performers. It is one of Chopin’s longest pieces, and is considered one of his greatest works.