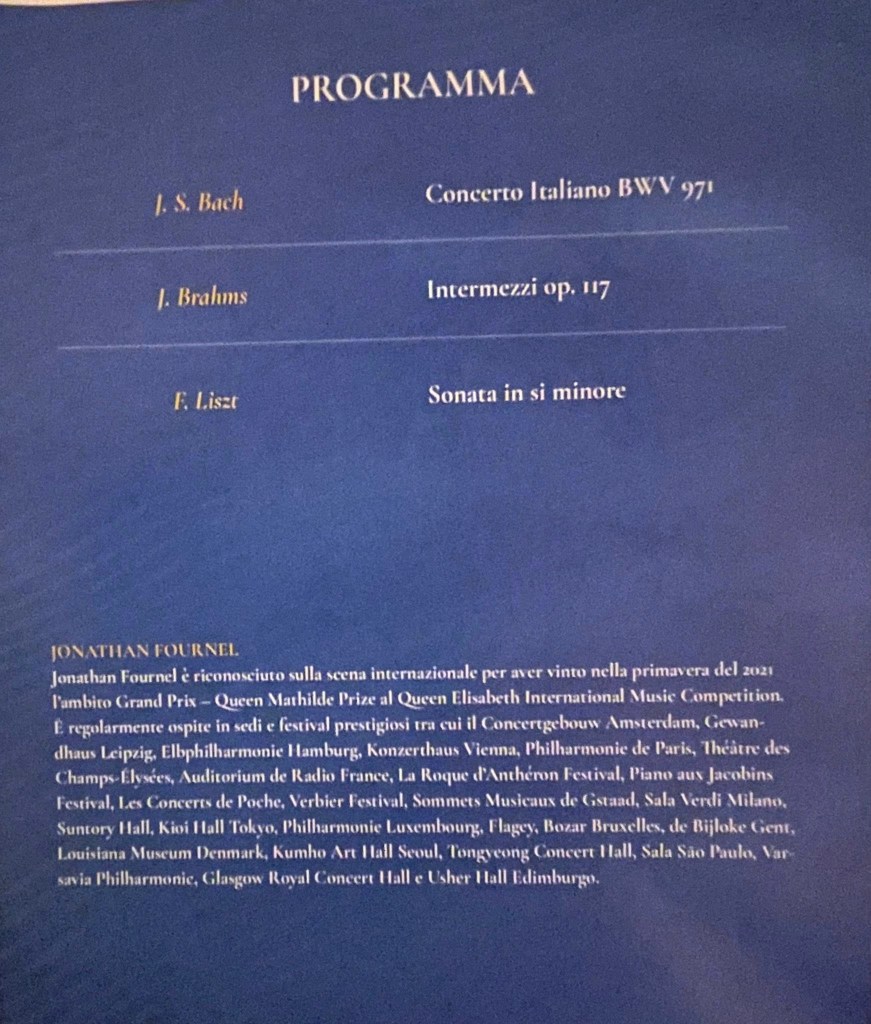

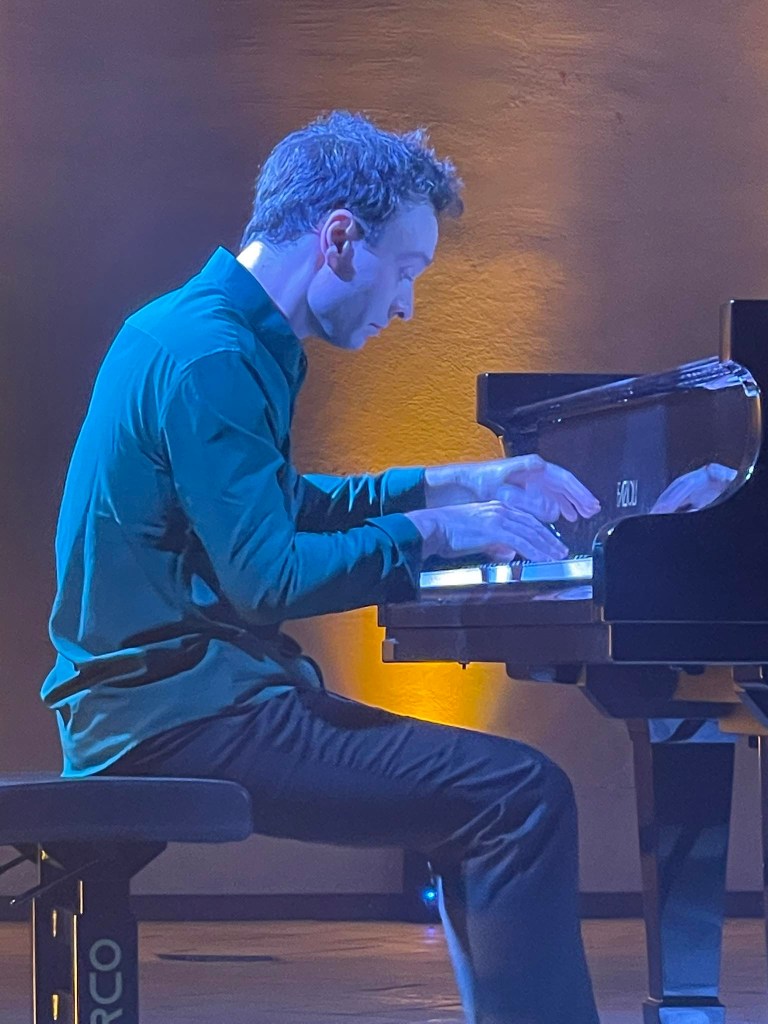

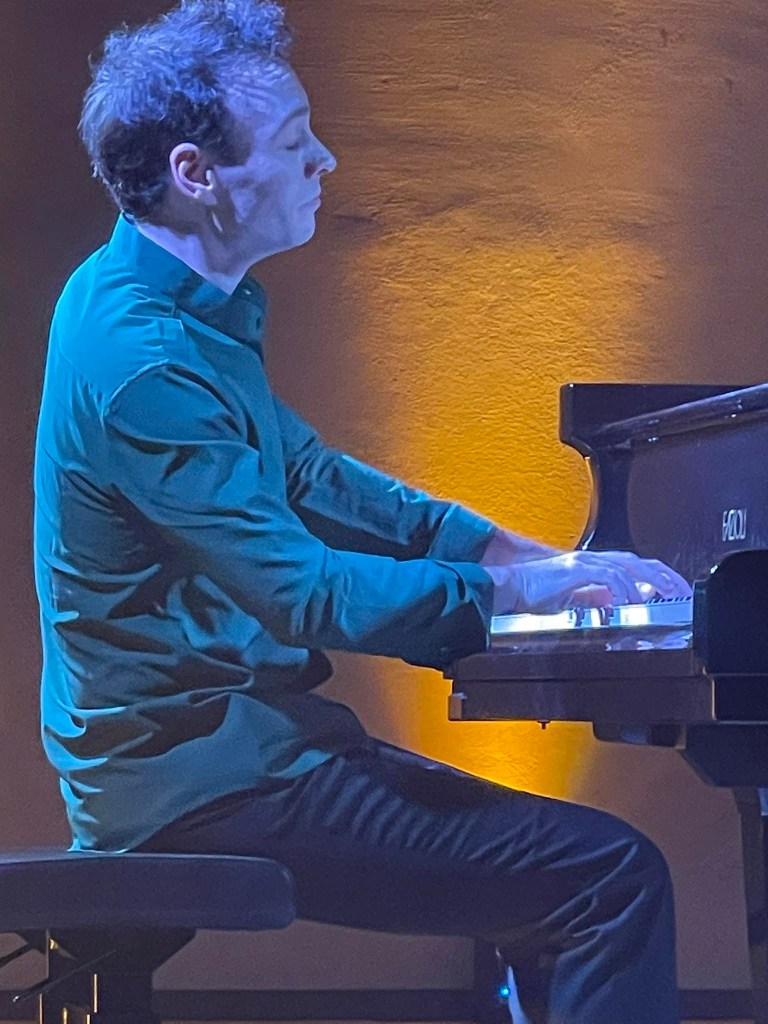

A star shining brightly in Fondi as the artistry of Jonathan Fournel shows how passion poetry and mastery can intoxicate and mesmerise the audience of the Riviera di Ulisse Festival of Luigi and Natalie Carroccia .

Bach played with a kaleidoscope of colour and aristocratic nobility.The Bach Italian Concerto was played with extraordinarily refined colouring that was respectful of the period it was written. Full of fantasy and dynamism in every note but with a very refined musical palette without ever loosing the dynamic drive that is so much part of the genius of Köthen. The slow movement was very expressive but strangely very orchestral with rich but delicate sounds (as Jonathan was to find in Brahms later too). Here there was an architectural shape of the nobility and authority of a thinking and feeling musician. The last movement sprang from his masterly fingers with dynamic drive and a rhythmic energy of exhilaration and ‘joie de vivre’, Counterpoints that were so clearly differentiated by contrasted dynamic levels of sound. There was also no rallentando or grandiose ending to ruin the architectural shape that had been created by the master of knotty twine so perfectly differentiated by Jonathan’s true pianistic mastery.

Brahms played with almost orchestral richness that was both tender and passionate.Three Intermezzi op 117 that Brahms described as ‘three lullabies of my grief’ were played with whispered luminosity and a delicately chiselled orchestral beauty. Op 117 n.1 is based on an anonymous Scottish Ballade : ‘lie still and sleep;

It grieves me sore to see thee weep’ ,where Jonathan found a beautiful gentle doubling of the tenor register. As the melody returned the gently rocking from the bass to the soprano created a frame of pure magic, with barely audible final notes placed with infinite delicacy and breathtaking beauty.There was the insinuating beauty of the second in B flat minor with a richness but also a tenderness and an ending of exquisite beauty. A central episode that has been described as :’man as he stands with the bleak, gusty autumn wind eddying round him’ was indeed played with a rich full tone of glowing beauty and timeless wonder. The third in C sharp minor is the most disturbing with it’s almost oriental feel to the opening doubling of the melodic line and which Jonathan transformed into a wondrous tone poem of beguiling insinuating beauty.

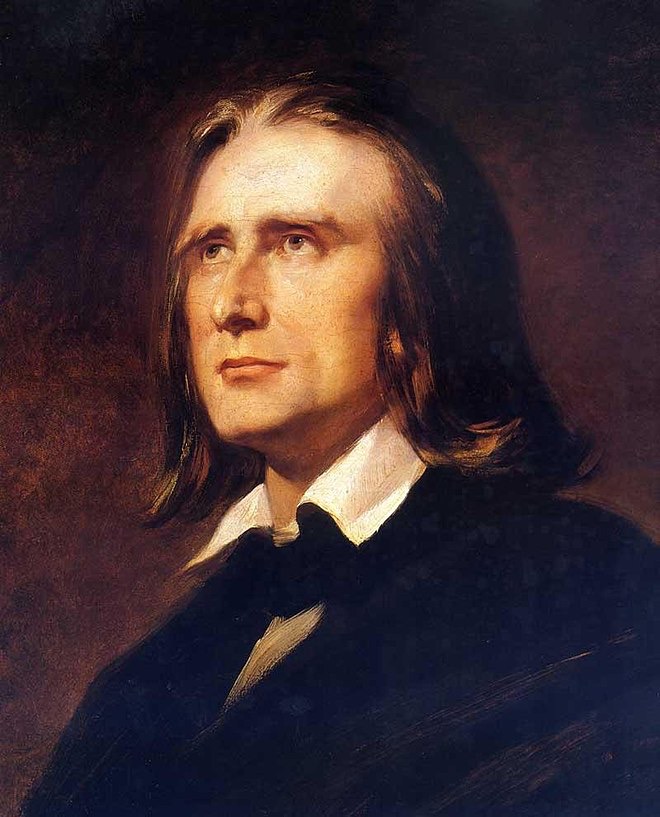

And finally the Liszt Sonata played with fearless abandon and respect for the pinnacle of the romantic piano repertoire.

Restored to its rightful place with breathtaking beauty and earthshattering conviction but above all the respect for the genius of Liszt, as Jonathan recreated this masterpiece as rarely ever heard since Gilels. I have never experienced the almost religious rite of the opening with hands poised as he was about to embark on a truly wondrous voyage. The dynamic values within forte may have been slightly the same but this was a man playing with passionate commitment and quite extraordinary technical mastery. As Barbirolli famously said of criticism of Jaqueline Du Pré ;’If you don’t play with passion and love when you are young what do you pare off when you are older’. Jonathan,like Du Pré, is a great musician and always foremost in his playing was the sense of line and an overall sense of balance. Sometimes at the height of passionate involvement suddenly reducing the sound so it could lead to the climax without any hard or ungrateful sounds. The sign of a great musician is the meaning that is given to the rests or silences between the notes and it was this that became so noticeable as Jonathan began the descent into the recapitulation after the searing intensity of the central movement. The gradual disintegration into descending scales like glistening jewels just coming to rest after such a traumatic experience was truly memorable for the energy that he could install in notes of such seeming simplicity. There were terrifying contrasts between the enormous sonorities of the chords and the touching delicacy of the recitativi. Passion and poetry combined in a truly memorable performance of this pinnacle of the romantic piano repertoire. The fearless mastery of the treacherous final octaves were played at a speed that would have put fear into any other pianist as they passed from the right hand to the left with quite extraordinary passionate involvement and remarkable accuracy.

The final visionary pages were played by a true poet but also a thinking musician, where rests I have never noticed before became as eloquent and meaningful as the notes. There were moments of aching silence as Jonathan reached the heights with three delicately placed chords, the last one played quieter than the others , as Liszt asks, and barely touching the final B. Moved by this moment of recreation as he involved us in this act of mutual communion that can only happen in live performance. Again it was the aching final silence that spoke even louder than the notes because we were all involved in this almost religious rite of recreation.

As Gilels so rightly said ‘live performance is like fresh food and recorded performances like canned food’. And as the ‘Bard’ said : ‘If Music be the food of love, please oh please play on’.

Exhausted but not completely spent this young man could still create a magic spell with the Bach-Siloti Prelude in B minor.The shadow of Gilels watching from above as this young man recreated the magic that was his many years ago.

A star was truly born tonight with Jonathan Fournel’s much awaited return to Italy after winning the Gold Medal at the Queen Elisabeth Competion in 2021 .

The very first competition in 1938 was won by Emil Gilels, could that be a coincidence or is great artistry born on these wings of song?

This is Gilels playing the same Bach-Siloti that Jonathan treated us to as an encore :

https://youtu.be/Yu06WnXlPCY?si=2W06QQaMd1O7Zc_a

He has collaborated with orchestras including the NHK Symphony Orchestra, Macao Orchestra, Royal Scottish National Orchestra, Orchestre Philharmonique du Luxembourg, Orchestre National d’Île-de-France, Orchestre de Chambre de Paris, Orchestre National de Bordeaux, Orchestre National de Lille, Orchestre National de Montpellier, Deutsche Radio Philharmonie, Nordwestdeutsche Philharmonie, Brussels Philharmonic, Belgian National Orchestra, European Union Youth Orchestra, NOSPR Katowice, Slovak Philharmonic and the Croatian Radio and Television Orchestra.

In 1938 Gilels and Flier set off to the Queen Elisabeth Competition. They were expected to uphold the victories of the Soviet violinists, lead by David Oistrakh a year earlier, and to return in triumph. Gilels was awarded the first prize and Flier took the third. Moura Lympany,second and Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli 7th !

The whole musical world began to talk about Emil Gilels. Following the competition he was meant to embark on a lengthy concert tour, including a tour of the USA. These plans were abruptly interrupted by the Second World War. On home soil Gilels became a hero: he received a medal for his achievements, was greeted by a welcome party upon his return and in the Soviet consciousness his name sounded in equal rank with the names of famous explorers, pilots and film stars. Final (29/05/1938) programme :

PYOTR TCHAIKOVSKY Concerto n. 1 in B flat minor op. 23

JOHANNES BRAHMS Variations on a Theme by Paganini op. 35 I

FELIX MENDELSSOHN Scherzo (A midsummer night’s dream )

RICHARD WAGNER Mort d’Yseult

MILY BALAKIREV Islamey

FRANZ LISZT Hungarian Rhapsody n. 6 in D flat major

JOSEPH JONGEN Toccata

Emil Gilels

Orchestre Symphonique de l’INR, dir. Franz André

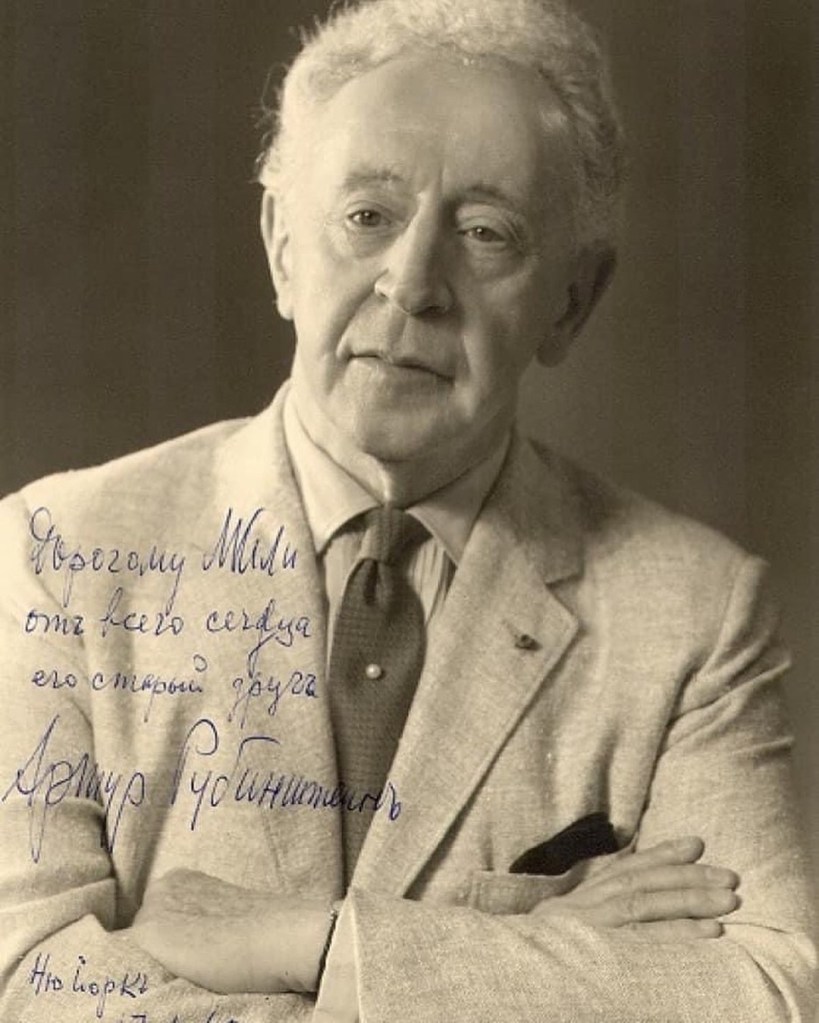

“from my heart, your old friend Arthur Rubinstein.”

17 January 1960

In May 1929, aged 12, Gilels gave his first public concert.In 1929, Gilels was accepted to the Odessa Conservatory into the class of Bertha Reingbald. Under the tutelage of Reingbald, Gilels broadened his range of cultural interests, with a particular aptitude for history and literature.

In 1932, Artur Rubinstein visited the Odessa Conservatory and met Gilels, and the two of them remained friends through the remainder of Rubinstein’s life.Rubinstein recounts that in hearing this red haired teenager he declared that if he ever came to the west Rubinstein may as well pack up his bags retire

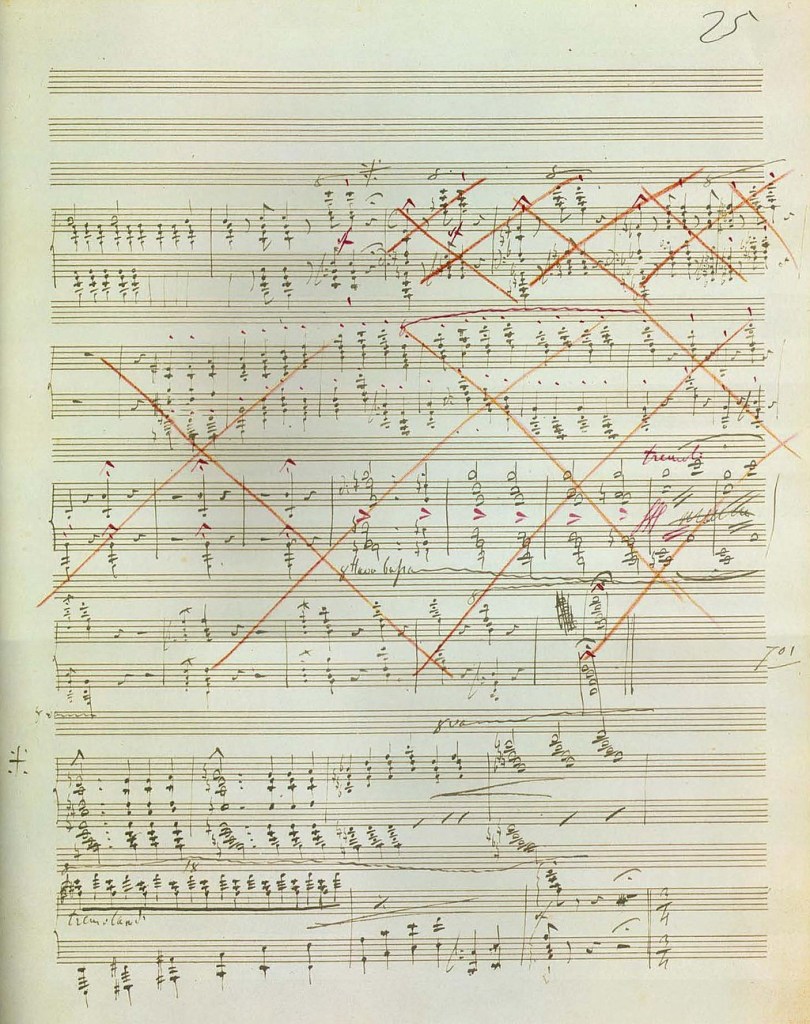

The Piano Sonata in B minor S.178 is in a single movement . Liszt completed the work during his time in Weimar, Germany in 1853, a year before it was published in 1854 and performed in 1857. He dedicated the piece to Robert Schumann , in return for Schumann’s dedication to Liszt in his Fantasie in C major op 17 .A copy of the work arrived at Schumann’s house in May 1854, after he had entered Endenich sanatorium. Clara Schumann did not perform the Sonata despite her marriage to Robert Schumann as she found it “merely a blind noise”.The Sonata was published by Breitkopf & Härtel in 1854 and first performed on 27 January 1857 in Berlin by Hans von Bulow. It was attacked by Eduard Hanslick who said “anyone who has heard it and finds it beautiful is beyond help”.Brahms reputedly fell asleep when Liszt performed the work in 1853, and it was also criticized by the pianist and composer Anton Rubinstein . However, the Sonata drew enthusiasm from Richard Wagner following a private performance of the piece by Karl Klindworth on April 5, 1855. Otto Gumprecht of the German newspaper Nationalzeitung referred to it as “an invitation to hissing and stomping”. It took a long time for the Sonata to become commonplace in concert repertoire because of its technical difficulty and negative initial reception due to its status as “new” music. However by the early stages of the twentieth century, the piece had become established as a pinnacle of Liszt’s repertoire and has been a popularly performed and extensively analyzed piece ever since

The complexity of the sonata means no analytical interpretation has been widely accepted. Some analyses suggest that the Sonata has four movements, although there is no gap between them. Superimposed upon the four movements is a large sonata form structure, although the precise beginnings and endings of the traditional development and recapitulation sections have long been a topic of debate. Others claim a three-movement form, an extended one-movement sonata form, and a rotational three-movement work with a double exposition and recapitulation. Liszt effectively composed a sonata within a sonata, which is part of the work’s uniqueness, and he was economical with his thematic material. The first page contains three motive ideas that provide the basis for nearly all that follows, with the ideas being transformed throughout having been inspired by Schubert’s Wanderer Fantasy and the transformation of themes that Liszt’s son in law Wagner was to make his own.

The quiet ending of the Sonata was an afterthought; the original manuscript contains a crossed-out ending section which would have ended the work in a loud flourish instead. Vladimir Ashkenazy considers these final two pages to be the most inspirational of all the romantic piano repertoire .