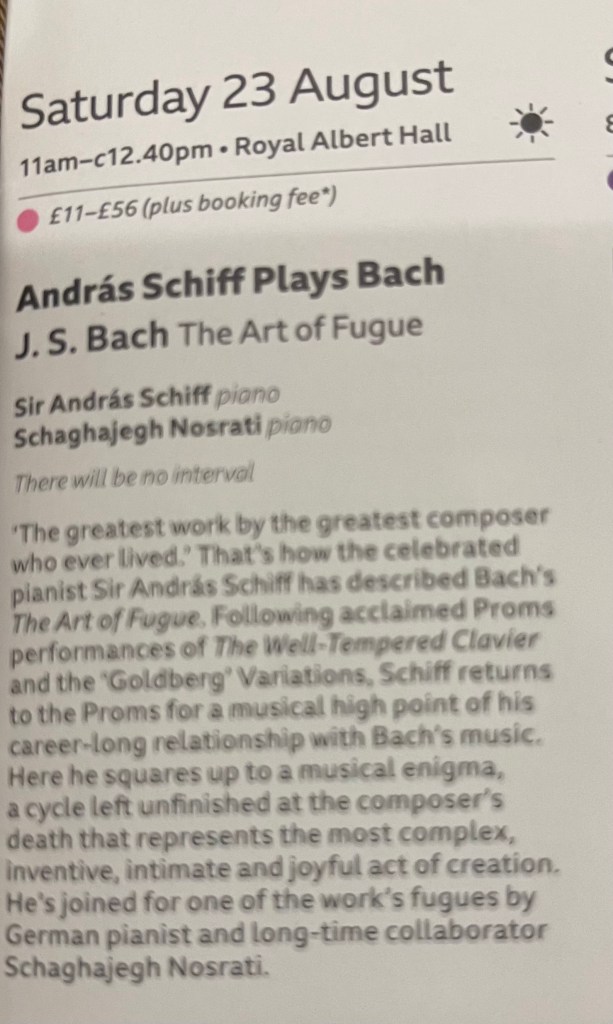

The Art of Fugue or the Art of understatement. Andras Schiff with humility and mastery held us captive in the name of Bach. Five thousand people listening with baited breath to ‘the greatest work of the greatest composer who ever lived’ .

A mystical and magical experience that ended with minutes of aching silence .

The silence of the innocent as even Bach did not know to what heights his genius would take him

With simplicity and integrity Andras Schiff took us on a wondrous voyage to oblivion.

There was no way out or no escape for the Genius of Köthen for whom life was music and music inextricably the very meaning of life .

Cristian Sandrin writes : ‘It was first time I heard the Art of Fugue being played in its entirety live. A momentous musical experience, merging in with a crowd of people in awe of Bach’s musical and mathematical genius. Schiff playing was infused with a certain mysticism, revealing the counterpoint in its spiritual glory. Calmness, stillness and sobriety permeated the slow moments and the strettos becoming momentous effusions of contrapuntal frenzy. We all gathered to hear the culmination of a long lost art, in the hands of Bach’s greatest apostle. Truly memorable. I also loved the fact that he played from the score – his humility towards Bach is boundless, the show was not a feat of memory, but a spiritual journey to be shared with everyone.’ https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2025/02/03/cristian-sandrins-new-goldbergs-ravish-and-astonish-perchance-to-dream/

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2025/03/23/william-bracken-at-bechstein-hall-mastery-and-mystery-of-a-great-musician/ https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2025/05/29/misha-kaploukhii-a-ray-of-sunlight-illuminates-the-1901-arts-club-hattori-foundation/

Born 21 March 1685 Eisenach Died 28 July 1750 (aged 65) Leipzig

The Art of Fugue, or The Art of the Fugue (German: Die Kunst der Fuge), BWV 1080, is an incomplete musical work of unspecified instrumentation by Johann Sebastian Bach . Written in the last decade of his life, The Art of Fugue is the culmination of Bach’s experimentation with monothematic instrumental works.

The work divides into seven groups, according to each piece’s prevailing contrapuntal device; in both editions, these groups and their respective components are generally ordered to increase in complexity. In the order in which they occur in the printed edition of 1751 (without the aforementioned works of spurious inclusion), the groups, and their components are as follows.

This work consists of fourteen fugues and four canons in D minor, each using some variation of a single principal subject, and generally ordered to increase in complexity. “The governing idea of the work”, as put by Bach specialist Christoph Wolff, “was an exploration in depth of the contrapuntal possibilities inherent in a single musical subject.” The word “contrapunctus” is often used for each fugue .

The autograph contains twelve untitled fugues and two canons arranged in a different order than in the first printed edition, with the absence of Contrapunctus 4, Fuga a 2 clav (two-keyboard version of Contrapunctus 13), Canon alla decima, and Canon alla duodecima.

The autograph manuscript presents the then-untitled Contrapunctiand canons in the following order: [Contrapunctus 1], [Contrapunctus 3], [Contrapunctus 2], [Contrapunctus 5], [Contrapunctus 9], an early version of [Contrapunctus 10], [Contrapunctus 6], [Contrapunctus 7], Canon in Hypodiapasonwith its two-stave solution Resolutio Canonis (entitled Canon alla Ottava in the first printed edition), [Contrapunctus 8], [Contrapunctus 11], Canon in Hypodiatesseron, al roversio [sic] e per augmentationem, perpetuus presented in two staves and then on one, [Contrapunctus 12] with the inversus form of the fugue written directly below the rectus form, [Contrapunctus 13] with the same rectus–inversus format, and a two-stave Canon al roverscio et per augmentationem—a second version of Canon in Hypodiatesseron

Simple fugues:

- Contrapunctus 1: four-voice fugue on principal subject

- Contrapunctus 2: four-voice fugue on principal subject, accompanied by a ‘French’ style dotted rhythm

- Contrapunctus 3: four-voice fugue on principal subject in inversion, employing intense chromaticism

- Contrapunctus 4: four-voice fugue on principal subject in inversion, employing counter-subjects

Stretto-fugues (counter-fugues), in which the subject is used simultaneously in regular, inverted, augmented, and diminished forms:

- Contrapunctus 5: has many stretto entries, as do Contrapuncti 6 and 7

- Contrapunctus 6, a 4 in Stylo Francese: adds both forms of the theme in diminution, (halving note lengths), with little rising and descending clusters of semiquavers in one voice answered or punctuated by similar groups in demisemiquavers in another, against sustained notes in the accompanying voices. The dotted rhythm, enhanced by these little rising and descending groups, suggests what is called “French style” in Bach’s day, hence the name Stylo Francese.

- Contrapunctus 7, a 4 per Augment[ationem] et Diminut[ionem]: uses augmented (doubling all note lengths) and diminished versions of the main subject and its inversion.

Double and triple fugues, employing two and three subjects respectively:

- Contrapunctus 8, a 3: triple fugue with three subjects, having independent expositions

- Contrapunctus 9, a 4, alla Duodecima: double fugue, with two subjects occurring dependently and in invertible counterpoint at the twelfth

- Contrapunctus 10, a 4, alla Decima: double fugue, with two subjects occurring dependently and in invertible counterpoint at the tenth

- Contrapunctus 11, a 4: triple fugue, employing the three subjects of Contrapunctus 8 in inversion

Mirror fugues, in which a piece is notated once and then with voices and counterpoint completely inverted, without violating contrapuntal rules or musicality:

- Contrapunctus inversus 12 a 4 [forma inversa and recta]

- Contrapunctus inversus 13 a 3 [forma recta and inversa]

Canons, labeled by interval and technique:

- Canon per Augmentationem in Contrario Motu: Canon in which the following voice is both inverted and augmented. The following voice, running at half-speed, eventually lags the first voice by 20 bars, making the canon effect hard to hear. Three versions have appeared in the autograph Mus. ms. autogr. P 200: Canon in Hypodiatesseron, al roversio [sic] e per augmentationem, perpetuus, Canon al roverscio et per augmentationem, and Canon p. Augmentationem contrario Motu, the third of which appears on the second supplemental Beilage.

- Canon alla Ottava: canon in imitation at the octave; titled Canon in Hypodiapason in Mus. ms. autogr. P 200.

- Canon alla Decima [in] Contrapunto alla Terza: canon in imitation at the tenth

- Canon alla Duodecima in Contrapunto alla Quinta: canon in imitation at the twelfth

Alternate variants and arrangements:

- Contra[punctus] a 4: alternate version of the last 22 bars of Contrapunctus 10.

- Fuga a 2 Clav: and Alio modo. Fuga a 2 Clav.: two-keyboard arrangements of Contrapunctus inversus a 3, the forma inversa and recta, respectively.

Incomplete fugue:

- [Contrapunctus 14] Fuga a 3 Soggetti: four-voice triple fugue (not completed by Bach, but likely to have become a quadruple fugue: see below), the third subject of which begins with the BACH motif , B♭–A–C–B♮ (‘H’ in German letter notation)

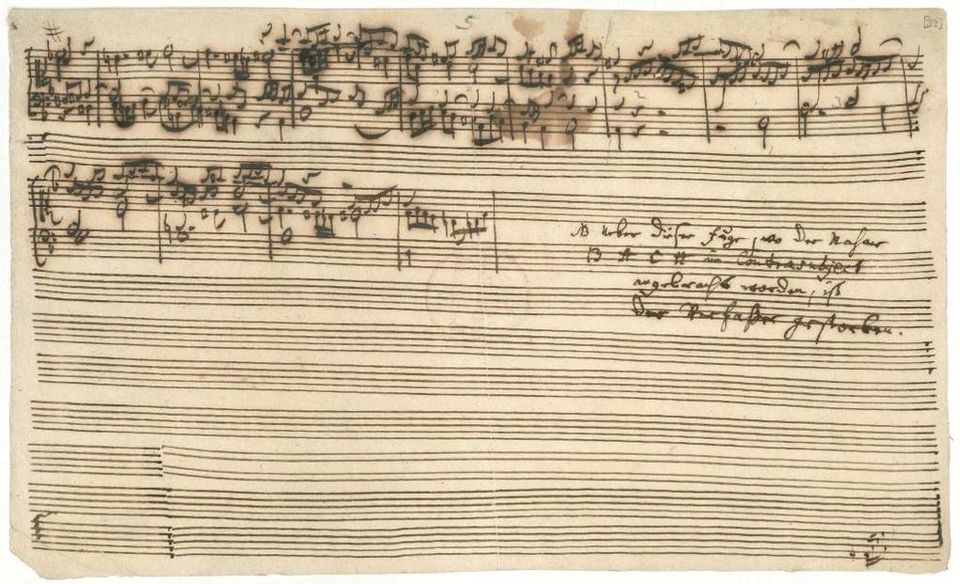

Fuga a 3 Soggetti (“fugue in three subjects”), also called the “Unfinished Fugue” and Contrapunctus 14, was contained in a handwritten manuscript bundled with the autograph manuscript Mus. ms. autogr. P 200. It breaks off abruptly in the middle of its third section, with an only partially written measure 239. This autograph carries a note in the handwriting of C.P.E. Bach, stating “Über dieser Fuge, wo der Name B A C H im Contrasubject angebracht worden, ist der Verfasser gestorben.” (“While working on this fugue, which introduces the name BACH [for which the English notation would be B♭–A–C–B♮] in the countersubject, the composer died.”) This account is disputed by modern scholars, as the manuscript was written in Bach’s own handwriting, and thus dates to a time before his deteriorating health and vision prevented him from writing, in their view probably 1748–1749.

It has long been thought that The Art of the Fugue was the last piece he was working on at the time of his death; evidence was the unfinished final fugue with the famous words added at the end of the manuscript, supposedly in Carl Philipp Emmanuel’s writing: “At the point where the composer introduced the name B-A-C-H in the countersubject to this fugue, the composer died.”

This is a beautiful and romantic story: imagine the old Bach, by then almost completely blind, painfully writing the last notes of the unfinished fugue, suddenly dropping the pen and exhaling his last breath… It would make for a great scene of a film.

Unfortunately, things didn’t happen that way.

- First and foremost, the name of B-A-C-H (musical notes in the German system: B-flat, A, C and B-natural) constitutes the core of the third subject of the fugue; it is not part of any countersubject. This might sound like hair splitting to non-musicians, but any member of the Bach family knew the difference between a subject and a countersubject. The famous words at the end of the manuscript could not have been written by Carl Philipp Emmanuel or any of Bach’s other sons.

- Second, Bach was already working on the edition of The Art of the Fugue at the end of his life. Never before did he ever prepare the edition of a piece or a collection that he had not yet finished composing; there is no reason to believe it was different with The Art of the Fugue. As for the unfinished final fugue, it is much more plausible to think that Bach had indeed completed it, but that the last bars are missing from the only manuscript we have and were not found by those who attended to the posthumous publication of the work. In all likelihood, Bach’s last project before his death was the completion of the Mass in B minor.

Another myth about The Art of the Fugue needs to be looked into carefully: it is not some kind of “theoretical” music intended for no specific instrument, as it is often said. Bach’s instrument was the keyboard, and The Art of the Fugue is undoubtedly a keyboard piece. Every single note can be played on it by a gifted player. The fact that Bach was writing the music on four independent staves doesn’t mean anything: this was common practice for contrapuntal keyboard music in the early 18th century.

Now the fact that The Art of the Fugue was intended for keyboard doesn’t prevent us from performing it on other instruments. Of all of Bach’s keyboard works, it is the one that offers itself the most naturally to orchestration or arrangement, and indeed many such reworkings have been realized in the past fifty years. (An important detail though: the four canons included in the collection are different animals, and three of them don’t really lend themselves to any other instrument than the keyboard ).

The Art of the Fugue is probably Bach’s keyboard work that benefits the most from a well-crafted transcription for other instruments. Although some great organists, harpsichordists and pianists have offered us remarkable interpretations of the piece, a performance with independent instruments, each one of them responsible for playing an individual line (in solo or tutti configuration), provides the listener with far greater legibility and allows a much easier understanding of Bach’s complex writing.