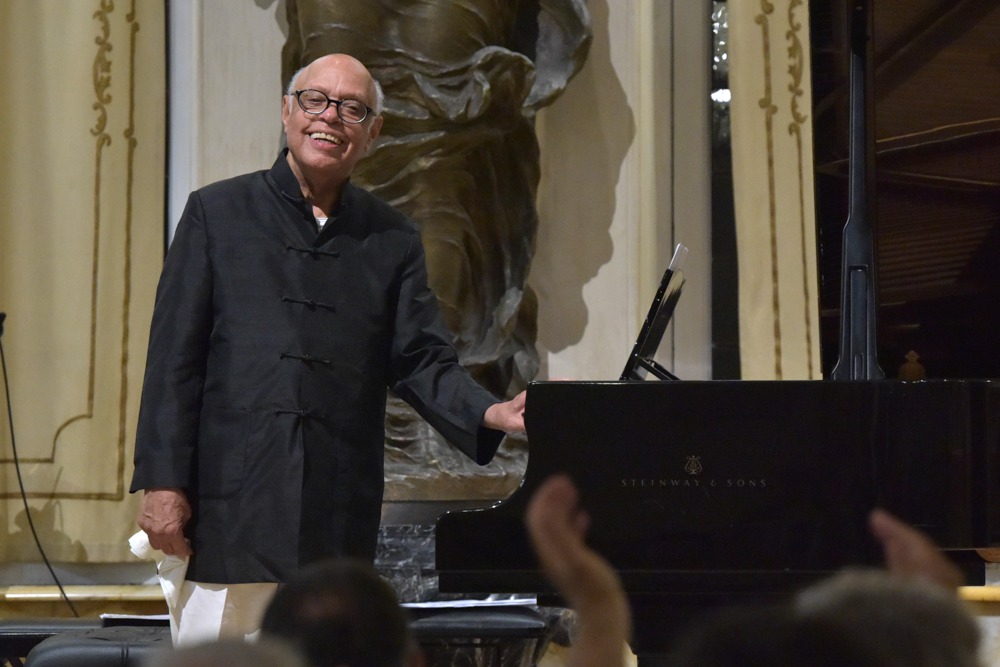

An amazing performance by this legendary 84 year old American born pianist who perfected his art in Italy with Renata Borgatti and Carlo Zecchi. Transferred permanently to Italy for almost sixty years he has created The International Piano Academy, Lake Como, of which the President is his close friend Martha Argerich. Born in the same year, it must have been quite a vintage year, as both Martha and Bill are astonishing and ravishing audiences world wide as never before! A teacher of many of the finest young musicians before the public today he has just returned from China and Korea where he is much sought after for his musical pedigree and insights. He spends most summers in Siena , where he receives privately a few carefully selected talented students in his studio. It was the enlightened Artistic Director of the Chigiana Academy in Siena, Nicola Sani, who had thought to convince William Naboré to play in the prestigious Palace of Count Chigi where many of the greatest musicians have flocked for the Summer months since the 1930’s, to share ideas amongst master musicians. Having just played this recital in Korea ,amazingly without the score , which is his latest CD to be released shortly. I have known ‘Bill’ for the past fifty years and shared many of the artists who played in my Euromusica season in Rome with his Academy in Como. Artists that included Rosalyn Tureck, Moura Lympany, Fou Ts’ong ,Peter Frankl and Steven Kovacevich. He had set up ten years after I had opened a theatre with my wife in Rome where I invited many of the greatest musicians to play in Rome ,some for the first time , having by a strange twist of fate strangely been ignored in Italy. By coincidence my wife, Ileana Ghione, I had met in Siena, when I was helping my teacher’s wife Lydia Stix Agosti with her course ‘Da Schoenberg ad oggi’.

Bill had asked me to listen to the rough proof of this recording which I was very honoured to do. He had recorded it mostly in one take and it was perfect and crystal clear with impeccable musicianship and technical mastery. There was really nothing to edit and I believe this is the recording that will appear in the Autumn.It was obviously the same performance that he gave publicly in the ‘legends’ series in the Chigiana International Music Festival which in his own modest words was an unexpected success :

‘The concert was an amazing success. It was sold out and many came back stage afterwards and said it was a life changing experience!! I have been stopped in the streets by students who were at the concert saying they had never heard similar, especially the SOUND!’

Ciao Bill,

Yesterday was truly a wonderful evening, and you gave a memorable concert!

Thanks again for your amazing and passionate performance.

Un abbraccio ,

Nicola Sani, Artistic Director of the Chigiana Academy.

1. Johann Sebastian Bach/Johannes Brahms:

Five Studies Anh. 1a/1. V Chaconne for the left hand (after the violin partita n. 2. in d minor BWV 1004)

2. Johann Sebastian Bach/Rafael Joseffy:

Gavotte en Rondeau transcribed from the Lute Suite in E major BWV 1006a

Carl Reinecke:

Sonata for the pianoforte for the left hand in C minor. Op. 179

3. Allegro moderato

4. Andante lento “Nemenj rozsam a tarlora”

5. Menuetto Moderato

6. Finale Allegro molto

Alexander Scriabine for the left hand

7. Prelude op. 9 n.1

8. Nocturne op. 9 n.2

Leopold Godowsky for the left hand

9. Elegy

10. Prelude on the name of BACH

Programme notes written by William Naboré for the recording of imminent release:

The absolute masterpiece in this collection of works for the left hand is the work of Brahms based on the Chaconne of Bach.

Contrary to what most people surmise, Brahms never described his work as a transcription but as a study for the left hand based on the Chaconne of Bach.

In fact, Brahms only discovered the Chaconne of Bach at the age of 44 in 1877.

In a letter at the time to Clara Schumann “Brahms wrote:

“The Chaconne is, in my opinion, one of the most wonderful and most incomprehensible pieces of music.

Using the technique adapted to a small instrument, the man writes a whole world of the deepest thoughts and most powerful feelings. If I could picture myself writing, or even conceiving such a piece, I am certain that the extreme excitement and emotional tension would have driven me mad. If one has no supremely great violinist at hand, the most exquisite of joys is probably simply to let the Chaconne ring in one’s mind but the piece certainly inspires one to occupy oneself with it somehow… There is only one way in which I can secure undiluted joy from the piece on a small and only appropriate scale, and that is when I play it

with the left hand alone.The same difficulty, the nature of the technique, the rendering of the arpeggios everything that conspires to make me feel like a violinist!”

Hence the genesis of the Bach/Brahms Chaconne Study for the Left Hand.

However, before going further, a word about the origin of the Chaconne, Bach’s longest single instrumental

work.

The Chaconne is said to have been imported into Spanish culture in the sixteenth century as a lively dance that originated from Latin America. By the 18th century the Chaconne had become in Europe a slow triple meter instrumental form. Obviously, Bach had not forgotten it was originally a dance.

The Chaconne of Bach was composed between 1717 -20, and it is said, in grieving memory of his first wife, Maria Barbara, who died while he was absent on a trip. In this sprawling and monumental work Bach expresses a depth and variety of feelings rarely encountered in music.

Brahms’ exuberant embrace of every note of Bach’s score is evident in his masterly study. This is not a transcription but a celebration of the highest order.

By transposing the score an octave down, Brahms is able to expand the range of the original while enriching the pianistic possibilities considerably.

Brahms also gives interpretive indications in his study that are most astute and effective yet he also

respects the Baroque practices that were known in his time.

The Chaconne is a series of variations on a repeated series of chords. It is the connection between these variations which make any interpretation of this particular realization of Bach’s Chaconne a supreme challenge.

Leopold Godowsky (1870-1938) was one of the world’s greatest pianists. He was held in the highest esteem in his lifetime by public, critics and public alike.

The astonishing thing is that he was largely self-taught. His point of pride, however, was his amazing technique which even his most famous colleagues envied and admired. He was considered the “Buddha” of the piano. Arthur Rubinstein said it would have taken him 500 years to acquire a piano technique like that

of Godowsky. He was also an important pedagogue who taught in many of the important institutions

around the world (Berlin, Vienna, New York, etc.) but after a particularly nomadic life finally settled down in New York after the First World War.

He was also an important and innovative composer, notably for the piano. Ferruccio Busoni said that himself and Godowsky were the only ones to have added anything of significance to keyboard writing since Franz Liszt.

Godowsky is best known for his transcriptions and paraphrases of other composers which are of a

diabolical difficulty. Even today, only the most intrepid pianists venture to play them. His most famous work in the genre is his 53 Studies on Chopin Etudes. But he is also called the “King of the Left Hand” as he wrote a sizable number of works exclusively for the left hand which include paraphrases of other composers and

original works.

It is, however, in the original works where Godowsky really shines as a great composer. I have chosen two his pieces of great beauty for this recording.

The Elegy for the left hand composed in 1929 is one of the most poignant and moving expressions of grief in music while the Prelude on BACH is one of the most exuberant!

The Gavotte en rondeau for solo violin is the third movement from the third Partita in E major (BWV 1006), the last work in a series of sonatas and partitas (BWV 1001 -1006) Bach composed around 1720. It is one of

Bach’s most popular smaller works and has been transposed for innumerable instruments including the marimba!

However, Bach himself made a transcription for the Lute as a suite (BWV 1006a) which in itself has

spawned countless other transcriptions, notably for the guitar. The modern piano is no exception and

probably the most well-known take on the piece is a pastiche of the entire suite by Rachmaninov which is a favorite of some pianists today.

However, a transcription for left hand on the piano is a rarity.

Rafael Joseffy, a brilliant Hungarian pianist (1852-1915) and pupil of Franz Liszt who settled in the United States made a faithful transcription of the lute transcription of Bach which was published in New York in 1888.

This is the transcription used for this recording.

In 1892, at the age of 20, Scriabin damaged his right hand (overuse syndrome) while practicing relentlessly Liszt’s Reminiscences of Don Juan and Islamey by Balakirev in an intense rivalry with his fellow student, Josef Lhevinne at the Moscow Conservatory. He immediately turned to composition to vent his rage and composed his first sonata, op.6 as a “cry against God and fate!

He eventually fully recovered the use of his right hand and, although he had a brilliant career as a concert pianist, he was always wary and fretful of his right hand.

In 1894, Scriabin made his debut as a concert pianist in St. Petersburg and in the same year composed the Prelude and Nocturne, op. 9 as a result of concentrating his virtuosity on his left hand.

It is interesting to note that Scriabin had small hands (he could barely stretch a 9th), but wrote piano works that require a broad span, especially in the left hand as we can witness in the Prelude and Nocturne, op. 9. Scriabin and Rachmaninov (who had huge hands) were classmates at the Moscow Conservatory and had a

complex and sometimes contentious relationship with during their careers, and esthetically, even if they didn’t always agree, they were close friends. Rachmaninov was a pallbearer at Scriabin’s funeral and played only Scriabin’s works in concert for one whole year after his death.

Scriabin was much closer to Chopin in his early years yet Rachmaninov always venerated Tschaikovsky. The Prelude and Nocturne op. 9 of Scriabin are close to the traditional romantic tradition to which Rachmaninov always adhered. However, the individual voice of Scriabin can be fully heard here.

The Prelude and Nocturne are some of the loveliest works of early Scriabin and have always been a concert favorite.

Carl Reinecke (1824-1910) is one of those “forgotten” mid era Romantic composers who was born in Denmark and became one of the most influential musicians of his time. In 1843, he settled in Leipzig where he became part of a group of musicians that included Schumann, Mendelssohn and Friedrich Wieck.

Although as a youth, he was a formidable violinist, he later became an equally formidable pianist and

became a widely sought after professor of composition and piano at the Leipzig Conservatory. His students included Grieg, Janacek, and Albeniz. He was also a notable interpreter of Mozart piano Concerti of which he wrote several cadenzas.

It is a mystery that a composer of such a renown in his lifetime was forgotten so quickly after his death.

This is probably due to the fact that his style never evolved over the years and he was composing in 1910 exactly like he did in 1843!

That said, his compositional output is enormous and, in all genres, and combinations of instruments and it is not surprising that he even composed a sonata for left hand, op. 179 in 1884.

In fact, the left-hand Piano Sonata of Reinecke is one of those hidden gems of the Romantic

piano repertoire, and a real masterpiece!

The first movement is troubled, mysterious yet forceful with a beguiling second theme.

The second movement, based on a Hungarian folksong “My love, do not enter a field that has been harvested” is also a most beautiful work.

The third movement, Menuetto, is more of a Valse-Caprice with a charming and lilting Intermezzo.

The finale, a fiery, virtuoso tour de force rounds out the sonata in heroic style.