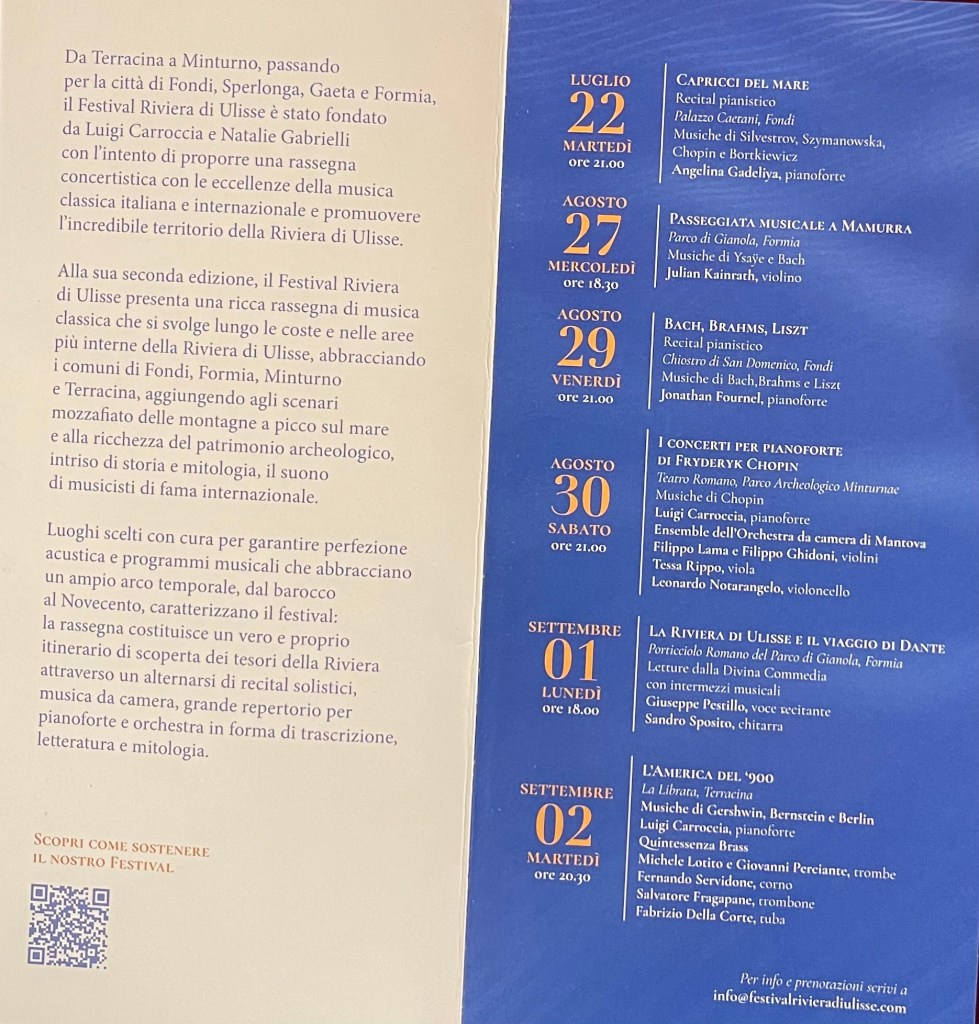

A celebration of Bel Canto in the imposing great hall of yet another Caetani Palace , this time in Fondi

The American – Ukraine pianist Angelina Gadeliya opened the second Festival Riviera di Ulisse, created by the pianist Luigi Carrroccia with his wife Natalie Gabrielli from nearby Terracina.

An eclectic programme of many works rarely heard in the concert hall might have struck terror into an audience in holiday mood. But this was a well thought out programme from Angelina Gadeliya, who is head of keyboard at one of America’s most prestigious universities.

Three pieces from Silvestrov’s ‘Kitsch – Musik’ of 1977 were unusually mellifluous, with a sense of balance and a kaleidoscope of ravishing colours very much in the bel canto style of Chopin. In fact one could almost discern the prelude in A major in the midst of this unexpectedly beautiful music. This is the later Silvestrov, when the composer was more concerned with colour and atmosphere than his earlier style of militaristic intellect. It was Boris Berman, in this very hall who was to give a masterclass demonstrating the music of his friend Silvestrov, whose works he has been championing, long before the composer was forced to flee his homeland, after the senseless invasion of his country. Angelina played with robust beauty of nobility and strength, with a mastery that could allow her to shape the music with an architectural shape whilst filled with poetic fantasy.

It was the same beauty that she brought to the enticing nocturne of Maria Szymanowska ( not to be confused with Karol Symanowski) Beautiful simple bel canto with scintillating ornaments of great beauty.

She coupled this with the beguiling insinuation of Chopin’s nocturne in B op 9 n 3. Radiance and beauty, with the same palette of colours that I remember from Lhevine’s famous piano roll recording, that bewitched me as a teenager, listening to it for the first time. Now Angelina could put the score to one side as she played two Chopin Mazurkas and the monumental Fourth Ballade, obviously part of her standard repertoire.

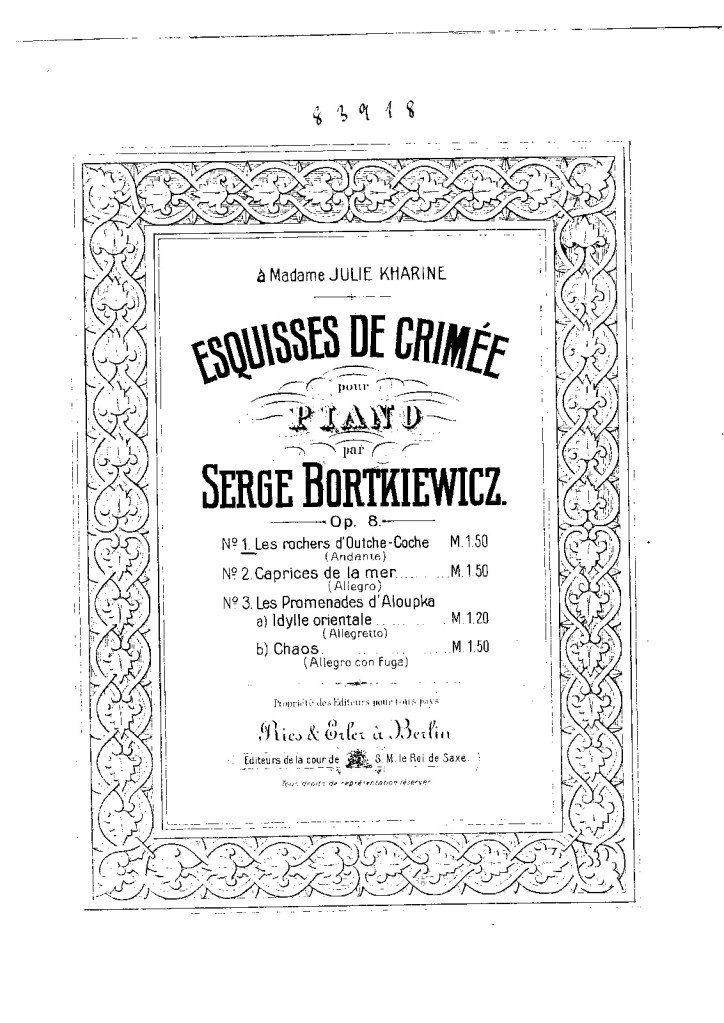

The Chopin Mazukas sprang to life with a rhythmic drive and imposing sense of dance. These, more than any other works by Chopin, show in 52 stops the nostalgia for his homeland that he was never to see again after his teens. ‘ Canons covered in flowers’ were how Robert Schumann was to describe these miniature tone poems, full of nostalgia and robust noble sentiment which Angelina played with knowing mastery. It was the same mastery allied to an extraordinary architectural clarity that she brought to one of the pinnacles of the pianistic repertoire, which is Chopin’s Fourth and last Ballade. Inspired by the poetry of Mickiewicz, who after some detective work on tonight’s interesting programme I discover had married Maria Szymanowska’s daughter! Small world indeed. This great ballade was played with poetry and nobility and a technical mastery that could allow the music to flow forward as the variations became ever more passionate and virtuosistic. A coda that was played with masterly control and musical vibrancy that was indeed the highlight of this short but enlightened window on composers physically far from their homeland but with hearts full of nostalgia and longing. Three Lisztian influenced pieces from Bortkiewicz’s ‘Crimean Sketches’ op 8 were played with scintillating pianistic brilliance, with the final flourish of ‘Capricci del mare’ thrown off with the same masterly ease with which it had given the title to this recital! There was a quixotic character to the dances of ‘Idillio Orientale’ played with a sense of colour and fantasy that was indeed full of the sounds of the east. Before bursting into the breathtaking arabesques of ‘Caos’. A strange title for a piece of such ravishment and scintillating beauty but which brought this hour of enlightenment to a brilliant end.

Another short piece from her ‘secret’ repertoire was her way of thanking such an attentive audience in what was the temperature of a Turkish bath.

Luigi and Natalie had thoughtfully provided the public with fans that helped keep the temperature bearable but looking like feux follets flitting around this august chamber of Palazzo Caetani.

Angelina Gadeliya , Professor in Residence of Piano, Coordinator of Keyboard Studies Praised for her “rich and resonant sound” (The New York Sun) and her ability to “make music speak” (The Colorado Springs Gazette), Ukrainian-American pianist Angelina Gadeliya leads a rich musical life as a soloist, chamber musician, new music expert, and educator. Her work with the NYC-based Decoda ensemble has frequently brought her to the stages of Carnegie Hall and the Juilliard School, as well as to Germany, South Korea, Abu Dhabi, Princeton University, Vassar College, the Trinity Wall Street series, and various New York locales. Ms. Gadeliya’s recent performances also include solo and chamber music recitals in such venues as New York’s Alice Tully Hall, Carnegie’s Weill and Zankel Halls, the Beijing National Center for the Performing Arts, the Curtis Institute of Music, and in prestigious concert halls of Canada, Israel, Mexico, Spain, Italy, Poland, and Ukraine. Her festival affiliations include her new summer piano program in Croatia- Dubrovnik Piano Sessions, the Amalfi Coast Music and Arts Festival, the Beijing International Music Festival and Academy, Music Fest Perugia, and she has also appeared at the Philadelphia Chamber Music Society, the Dakota Sky International Piano Festival, the Beethoven Master Course in Positano, Italy, the Bach Festival of Philadelphia, the Reynosa International Piano Festival in Mexico, the Metropolitan Museum of Art lecture series, and the 2007 Emerson String Quartet’s Beethoven Project at Carnegie Hall. Ms. Gadeliya has appeared with orchestras across the US and has collaborated with such artists as Lucy Shelton, Anton Miller, Mihai Tetel, Jean-Michel Fonteneau, James Conlon, David Stern, Andrew Manze, David Bowlin, principal players of the New York Philharmonic, and the internationally acclaimed Mark Morris Dance Group. Last season she was featured as soloist with the Hartford Symphony Orchestra in Kenneth Fuchs’ new piano concerto, “Spiritualist.” Ms. Gadeliya serves as Artistic Director of the Fryderyk Chopin Society of Connecticut and is the Assistant Professor in Residence of Piano and Director of Keyboard Studies at the University of Connecticut in Storrs.A passionate advocate of new music, Ms. Gadeliya has given numerous premiers of new works and has worked closely with composers Frederic Rzewski, Sarah Kirkland Snider, Richard Danielpour, Richard Wilson, John Adams, Thomas Adès, Steve Reich, Steven Mackey, Daniel Bjarnason, and John Harbison, among others. She has two upcoming new album releases in 2025- Piano Music of Richard Danielpour as well as an album of solo and chamber works by Chopin and Szymanowska. She holds degrees from the Oberlin Conservatory, the Juilliard School, Mannes College, and has a doctorate from Stony Brook University. Her principal mentors include Angela Cheng, Pavlina Dokovska, and Gilbert Kalish. Ms. Gadeliya currently resides in Glastonbury, CT with her husband Misha and their three children, Felix, Anastasia, and Luke. For more information, please go to www.angelinagadeliya.com.

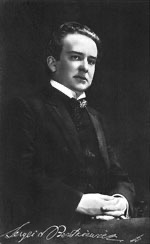

born: 28 February 1877

died: 25 October 1952

Sergei Eduardovich Bortkiewicz was born in the Ukrainian city of Kharkov on 28 February 1877. His background and musical training mirrors that of many of his contemporaries. His mother was an accomplished pianist (a situation so common with composers of the time that it now seems almost a cliché) and co-founder of the Kharkov Music School, affiliated to the Imperial Russian Music Society where Bortkiewicz was to have his early training. He studied piano there with Albert Bensch and early influences included Anton Rubinstein and Tchaikovsky, both of whom visited the school and took part in concerts there.In 1896 Bortkiewicz enrolled at the St Petersburg Conservatory. As before in Kharkov he concentrated on his studies as a pianist, studying with Karl van Ark (a pupil of Leschetizky), but also joined the theory class of Anatol Liadov. He enrolled at the Leipzig Conservatory in the Autumn of 1900, studying composition with Salomon Jadassohn and piano with Alfred Reisenauer. Reisenauer was a pupil of Liszt and a celebrated virtuoso. Bortkiewicz had first heard him play at the Kharkov Music School and soon became a devoted disciple. Bortkiewicz himself never became the ‘great pianist’ he had hoped to be and in his memoirs he notes, with some regret: ‘Reisenauer was a pianistic genius. He did not need to practise much, it came to him by itself … he thought and spoke very little about technical problems. Although I must thank my master very much as regards music, I had to realize later that I would have done much better if I had gone to Vienna in order to cure myself under Theodor Leschetizky of certain technical limitations, which I tried to overcome only instinctively and with a great waste of time.’ In July 1902 Bortkiewicz completed his studies at the Leipzig Conservatory and, during a brief stay with his parents on their country estate, became engaged to his sister’s school friend Elisabeth Geraklitova. He was to marry her in July 1904. In his memoirs Bortkiewicz remarks: ‘Now I was married. A new period of my life began.’ This new period was marked by his turning seriously to composition for the first time. Although his Op 1 (whatever it was) appears to be lost and his Op 2 set of songs remained unpublished, in 1906 his Quatre Morceaux for piano, Op 3, were published by the Leipzig firm of Daniel Rahter. From 1904 until the outbreak of the First World War Bortkiewicz lived in Berlin (spending his summers with his wife in Russia). He taught briefly at the Klindworth-Scharwenka Conservatory and continued to give concerts (not only in Germany but also in Vienna, Budapest, Paris, Italy and Russia)—although he increasingly played only his own compositions. When hostilities began in 1914 Bortkiewicz was placed under house arrest and finally deported back to Russia via Sweden and Finland. It was a crushing blow for him. He loved Germany and had made his home there for so many years—but worse was to follow. Initially, settled back in Kharkov, things seemed promising. He started teaching again, drawing around him a number of promising students who had studied in Moscow and St Petersburg during peacetime and who now remained in southern Russia as the war continued. He finally met Scriabin and Taneyev in Moscow and, confident that the war would end soon, Bortkiewicz set about rebuilding his career. On 25 March 1918 the Germans finally occupied Kharkov. The Bortkiewicz family estate at Artiomovka was completely plundered and finally in the autumn of 1919 Bortkiewicz and his wife fled to Sevastopol in the Crimea. There they waited in rented rooms overlooking Yalta harbour, desperate for a ship that would take them away from Russia and back to freedom. Finally they were able to push themselves on board a merchant steamer, the Konstantin, bound for Constantinople. When they arrived they were penniless.A chance introduction to Ilen Ilegey, court pianist to the Sultan, saved the situation. The Turkish pianist was impressed by Bortkiewicz’s compositions and helped by recommending him to important dignitaries in the city. Before long, Bortkiewicz was giving piano lessons to the daughter of the Court Conductor, the daughter of the Belgian Ambassador and the wife of the Yugoslavian Ambassador. He found himself a guest at all the large receptions in the magnificent embassies. Although he now had plenty of work, he missed the music and culture of Europe—in Constantinople there were no concerts, theatre or intellectual interests. Finally, Bortkiewicz managed to re-establish his old business contacts with the publishing firm Rahter. He decided to move to Vienna and on 22 July 1922 he and his wife arrived at the Austrian capital.The move to Vienna was to be his final one. He became an Austrian citizen in 1926 and taught piano at the Vienna Conservatory. Bortkiewicz’s memoirs, although written in 1936, cover his life only until his arrival in Vienna in 1922. We know little about his subsequent life and career, except that he seems to have been held in high esteem in his new home. On 10 April 1947, in his seventieth year, the Bortkiewicz Society in Vienna was formed. It proved to be short-lived and Bortkiewicz himself died in Vienna on 25 October 1952. A substantial proportion of his published works was lost in the destruction of the Second World War and, with his remaining works increasingly difficult to obtain, his memory soon faded. In 1977, twenty-five years after his death, the Viennese civic authorities levelled his grave in the city cemetery. In October 1936 Bortkiewicz had finished his memoirs with these words: ‘The one, who lives along with a crescendo of culture, should be praised as being happy! Woe to him who has gone down with the wheel of history! Vae victis!—And the present? Where are we headed: up—or down?—Oh, if it would soon go up!’As one would expect, Bortkiewicz’s output contains many works for his own instrument, the piano. He wrote two piano sonatas, many sets of pieces for piano and three piano concertos (the second for the left hand). He also completed a violin concerto and a cello concerto as well as an opera, Akrobaten, two symphonies, songs and chamber music. It is sad that so many of his works are lost and it can only be hoped that in time some surviving copies of his missing opus numbers may come to light.Bortkiewicz described himself as a romantic and a melodist, and he had an emphatic aversion for what he called modern, atonal and cacophonous music. Bortkiewicz’s work reflects little innovation compared to many of his contemporary composers. He covered no new ground, but built on the structures and sounds of Chopin and Liszt, with the unmistakable influences of early Scriabin and Rachmaninov. Like Medtner, the essential characteristics of his style were already present in his earliest compositions, from around 1906, although his later music is more personal, poetic and nostalgic. Melody, harmony and structure were essential building blocks for his musical creations. His training with van Ark, Liadov, Jadassohn, Piutti and Reisenauer ingrained a rigorous professionalism. His colourful and delicate imagination, his idiomatic piano-writing and sensitivity to his musical ideas, combined with his undisputed gift for melody, result in a style that is instantly recognizable, attractive and appealing to many listener. .During his life, Bortkiewicz was oppressed and persecuted by both Soviet and Nazi regimes. A brilliant pianist and composer, he was also a refugee and a survivor of two world wars and a civil war. The style of Bortkiewicz’s music derives from the great Romantic composers of the 19th century. He adopted Liszt’s rich and brilliant piano writing, Chopin’s lyricism and humanness, imagery of Schumann’s character pieces, Wagner’s imaginative harmony. The trademark of Bortkiewicz’s music is his captivating poetic melodies.

His Esquisses de Crimée (Crimean sketches) are powerfully descriptive of the area around the small town of Alupka, 10 miles west of Yalta and with their whiff of the orient are charming. The last of them subtitled Chaos brings Liszt immediately to mind. Les Rochers d’Outche-Coche; Caprices de la Mer; Idylle Orientale ; Chaos

While it is easy to come to the conclusion that this composer is a musical ‘clone’ of other well-known ‘romantic’ composers, it would be both unfair and inaccurate, such is the inventive nature that Bortkiewicz demonstrates in every bar.

Her compositions —largely piano pieces, songs, and other small chamber works, as well as the first piano concert etudes and nocturnes in Poland—typify the stile brillant of the era preceding Chopin . She was the mother of Celina Szymanowska , who married the Polish Romantic poet Adam Mickiewicz.

Her professional piano career began in 1815, with performances in England in 1818, a tour of Western Europe 1823–1826, including both public and private performances in Germany, France, England (on multiple occasions), Italy, Belgium and Holland. A number of these performances were given in private for royalty; in England alone during 1824, her performance schedule included concerts at the Royal Philharmonic Society (18 May 1824), Hanover Square (11 June 1824, with members of the royal family present) and other performances for several English dukes. From 1822 – 1823, Szymanowska toured in many cities in the 19th century Russian territories, including Moscow, Kiev, Riga and, St Petersburg. There she performed at the Imperial Court and received the title of First Pianist. In St Petersburg, Maria met Hummel and performed with him. Her playing was very well received by critics and audiences alike, garnering her a reputation for a delicate tone, lyrical sense of virtuosity and operatic freedom. She was one of the first professional piano virtuosos in 19th-century Europe and one of the first pianists to perform memorized repertoire in public, a decade ahead of Franz Liszt and Clara Schumann. After years of touring, she returned to Warsaw for some time before relocating in early 1828, first to Moscow and then to St. Petersburg, where she served as the court pianist to the Empress of Russia Alexandra Feodorovna.

Szymanowska composed around 100 piano pieces. Like many women composers of her time, she wrote music predominantly for instrumentation she had access to, including many solo piano pieces and miniatures, songs, and some chamber works.Her Etudes and Preludes show innovative keyboard writing; the Nocturne in B flat is her most mature piano composition; Szymanowska’s Mazurkas represent one of the first attempts at stylization of the dance; Fantasy and Caprice contain an impressive vocabulary of pianistic technique; her polonaises follow the tradition of polonaise-writing created by Michal Kleofas Ogiński. Szymanowska’s musical style is parallel to the compositional starting point of Frédéric Chopin; many of her compositions had an obvious impact on Chopin’s mature musical language.

Silvestrov began private music lessons when he was 15. After first teaching himself, he studied piano at the Kyiv Evening Music School from 1955 to 1958 whilst at the same time training to become a civil engineer . He attended the Kyiv Conservatory from 1958 to 1964, where he was taught musical composition by Borys Lyatoshynsky, and harmony and counterpoint by Levko Revutsky . He then taught at a music studio in Kyiv

Silvestrov was a freelance composer in Kyiv from 1970 to 2022, when he fled from Ukraine following the Russian invasion in February. He lives in Berlin.

The piano cycle Kitsch-Music (1977) is one of the most impressive examples of his “metaphorical style” (V. Silvestrov). Although they come from various creative periods, the works all demonstrate his unique way of thinking and composing. This becomes apparent in the way he notates even the most minute nuances in the areas of duration, dynamics, and tempo. Particular attention must be paid to his use of the pedal: the composer is of the opinion that it plays a role as a separate overtone voice. In this edition the works composed in the 1960s have been revised. Performance marks which occur in Silvestrov’s later works (such as “leggiero” and “dolce”) have been added, as have a number of tempo, dynamic and pedal marks.

“The author gives the description ‘kitsch’ an elegiac and not an ironic sense.” — Silvestrov.

Kitsch — which the Oxford English Dictionary defines as “art characterized by worthless pretentiousness” — is despised, when it is despised, for intolerably lying. It says it is the most natural thing in the world when it isn’t; it says the world is fine when isn’t; it says it is a friend, our intimate companion, when in fact, no one has any idea who it is. But people often buy kitsch because it lies well enough; it works seductively, insidiously, and gets under the skin or into the back of the mind, inserts its forged signature into consciousness like a long-dormant memory. In this sense, Silvestrov’s Kitsch Music could be admitted into the category. Discussing this collection of five short piano pieces from 1977, the composer seems to imagine some of the most essential tattoos of kitsch: He works in the world of the copy — these pieces feel like fake Schumann, fake Schubert , fake Chopin, so full of the generic formulae of nineteenth century salon music. He expresses a desire for evoking the perfume along with the product: “It is to be played very softly (pp) and extremely softly (ppp), as if from a distance…” More importantly, he aspires the music to trick the listener, to “lie” much like kitsch seems to “lie”: “It is to be played very tenderly, in a tone buried deep inside, as if one was carefully jogging the listener’s memory with the music, so that the music would sound an inner awareness, as if the listener’s memory itself was singing this music.” But don’t let that fool you: This isn’t quite kitsch. Yes, the music is cheesy, even perhaps needlingly discomfiting in its sweetness. But unlike kitsch, Silvestrov’s score doesn’t repress its lie; its tragedy and its deathliness are written into it — “elegy” not “irony.” And so rather than fake Chopin, it is something like the misted-over recollection of Chopin, or perhaps the ghost of Chopin; kitsch, the deadly stink of the generic copy, is transcended by the whiff of an actual specter, not at all an intentioned copy but an unintentional visitation, as specters are wont to impose (and here, no line is drawn between the involuntary activities of the undead and those of forgotten and now-resurrected memories). The ensuing pieces, performed ideally, are not sentimental but haunted by sentiment, just as they are haunted by tones, gestures, and feelings that they make no presumption to actually incarnate. The ambient presentiment, the perfume of presence, is not backed by actual presence; it is kept aloft, it wafts and fades, without ever settling on a solid. This is, then, not music, not really even “kitsch-music” in the literal sense: It’s more an air vibrating with “semantic overtones,” an amnesia acoustically undone. And kitsch, as the predigested “synthetic” art Clement Greenberg once defined, is limned with a self-consciousness antithetical to the synthetic. Or, maybe more to the point: Silvestrov’s little piano pieces are renditions of synthetic, spied with the unsynthetic ear.