RICHARD WAGNER (1813-1883)

Schmachtend (Elegy in A flat major), WWV 93 (1881)

Eine Sonate für das Album von Frau M.W. (Mathilde Wesendonck), WWV 85 (1853)

Blasio Kavuma

Prelude for Piano (commissione del Deal Music & Arts Festival)

FERENC LISZT (1811-1886)

Isoldens Liebestod – Schlußszene aus Richard Wagners Tristan und Isolde, S447

(1867, revised 1874)

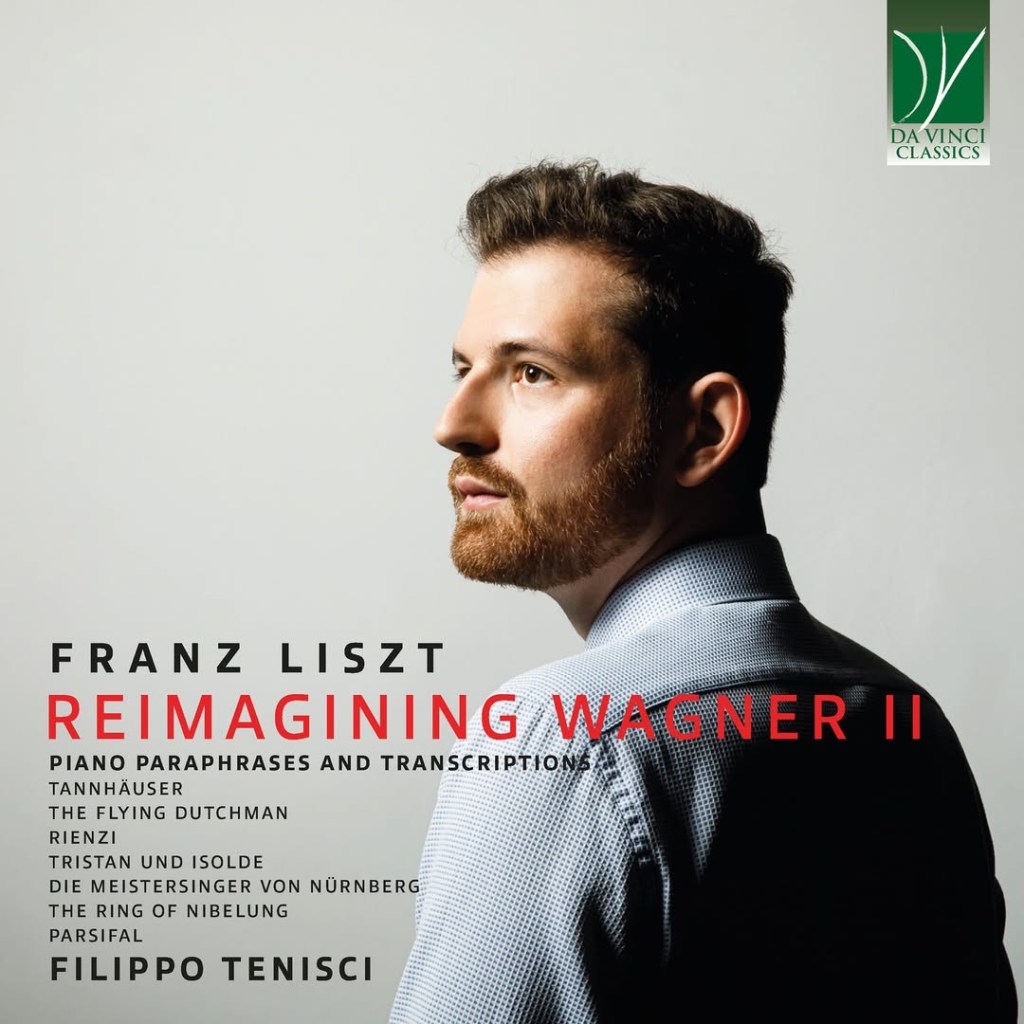

Ouverture zu R. Wagners Tannhäuser, S442 (1849)Wagner and Liszt embark in Deal today with Filippo Tenisci at the helm

A standing ovation and a taste of mushy peas were the just reward for a remarkably dedicated young artist who could transmit Wagner’s genius with a kaleidoscopic palette of colours. Adding Wagners son -in- law’s demonic pianistic genius too, as Liszt brought Wagner’s orchestra into the elite salons of the day with a heroic transcendental pianism that was exhilarating and overwhelming.

Two early original pieces by Wagner showed already his search for colour and insinuating counterpoints. Commissioned especially by the Festival to play a work from 2015 by the composer in residence and also to pair it with Wagner’s much neglected ‘Wesendonck’ Sonata. In fact the whole of this first half of the programme was played with barely whispered tones of great beauty. Filippo caressing the keys with gentle stroking movements gave a radiance and beauty to this fine Yamaha piano donated some years ago to Deal and that sits so proudly in their Town Hall.

The Elegie written just two year before the composers death is a page of etherial musings where the personality of the composer of the Ring cycle is apparent from the insinuating counterpoints of gently woven intricacy. This was followed by the Sonata, somewhat in the same mood of deep introspection and whispered beauty, even though written when the composer was only in his forties. It did, however, have a moment in its twelve minute life when it burst into life but not with the Lisztian histrionics that were to come later in the programme. It was a work of very subdued deeply felt expression of dark passion. Filippo had learnt it especially for the Festival and as he remarked afterwards it deserves to be heard more often in the concert hall. He played it with great authority and passionate conviction finding a refined palette of colours with a sense of touch that was like someone swimming and creating gentle waves where Wagner’s knotty counterpoints could mingle within Wagners unmistakable architectural sense of direction.

The other work that Filippo had learnt especially for the festival was by the composer in residence Blasio Kavuma.To quote the composer : ‘it was composer off the back of the String Trio and in it’s eight minutes of life uses highly chromatic harmonies and syncopated counterpoints, alluding to the preludes of Debussy, but also searching for its own identity’. It was an interesting work and one could see why the festival wanted it to be linked to the Wagner, because it uses very much the same delicate palette of colour. A continual outpouring of sounds in a mist of Debussian harmonies .A long slow meandering of great beauty that has a life of it’s own without any particular architectural shape.

Adding Liszt’s pianistic genius in a potent mix of two giants joined by marriage not only of Liszt’s daughter but also by their prophetic genius.The two Liszt re- workings of Wagner are both pianistic show pieces.

The ‘Liebestod’ is a piece often played in the concert hall and is a marvellous work for piano where Liszt’s admiration and love for the work of his son-in-law shines through with quite remarkable pianistic colours. An extraordinary ability to convey the very essence of the last opera that Liszt was to hear before his death and that Filippo played with ravishing colours. A passionate involvement with sumptuous rich sounds alternating with barely whispered secrets of refined glowing beauty.

The Tannhäuser overture was played in the uncut version and used to be the war horse of many notable virtuosi – Moisiewitch in particular.

https://youtu.be/XKDYla5C5cA?si=TymnVxQTbeeEBrDz

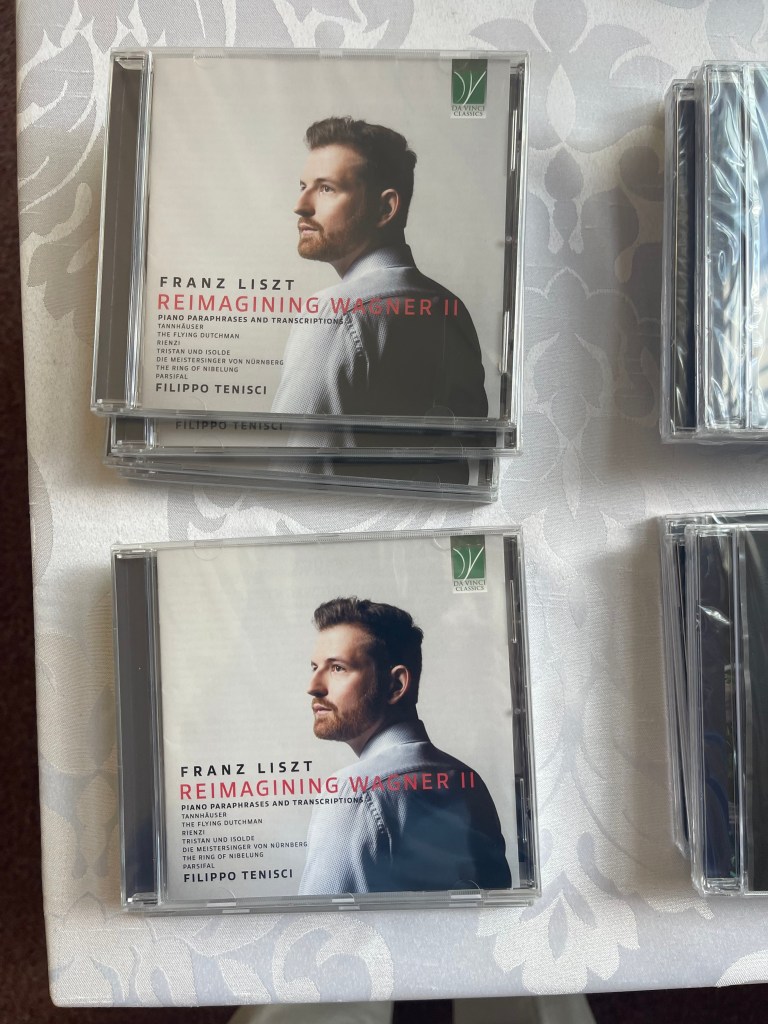

It was good to hear it in the concert hall again and it was a rousing ending to this very interesting concert. Fearlessly played with brilliance and a technical mastery that allowed Filippo to negotiate the transcendental difficulties that Liszt adds to his first transcription of a work by Wagner. Scintillating interludes with streams of notes thrown off with knowing ease as the ‘brass band’ climaxes built up to to the final might theme. Elaborated by Liszt with alternating octaves whilst at the same time maintaining the full sumptuous Tannhäuser theme in the centre of the keyboard. A ‘tour de force’ of ‘three handed pianism’ that brought a standing ovation from this very full hall, intent of buying this young pianist’s CD’s dedicated to Wagner/Liszt to take home with them to prolong the enjoyment they had found today.

‘Nobody needs to make too fulsome a claim for Wagner’s pianoforte music: His two early sonatas and the Fantasy show a young composer wrestling with form and content, but with only the most imitative of character. There is a later group of slighter works from his time in exile in Zurich, but even there we do not see much of the surefootedness of Wagner the experienced and successful opera composer. A couple of reasons spring to mind: Wagner was really no pianist, although he had worked as a jobbing repetiteur in Paris; Wagner the composer generally required external impetus, usually from poetry and legend. So it may be observed that hissettings of Mathilde Wesendonck poems are extraordinarily imaginative, whilst the one-movement Album-Sonata that he wrote for her is more of a curate’s egg. That said, there are touches of inspiration, evident immediately in the wonderful modulation that takes us mercurially from the home key of A flat major to C major (bar 25 onwards), and shortly after that, some examples of his trademark melodic ornament of the four-note turn, familiar in virtually every Wagner compositionfrom Rienzi to Parsifal. For these features we must therefore be forgiving of the comparatively unimaginative development section!

Wagner’s later piano pieces are all Album-Leaves, and often more interesting than might at first appear. The last of them, dating from 26th December 1881, was not published in Wagner’s lifetime, and the familiar sobriquet Elegie does not stem from the composer, who merely marked a curious tempo direction: Schmachtend (Languishing). Despite occasional commentaries attempting to connect the musical content of these dozen bars with Tristan (and misdating the work by more than 20 years) or the recently-completed Parsifal, the theme is clearly related in harmony, melody and expression to the slow movement – Die Abwesenheit (Absence) – of Beethoven’s opus 81a sonata: Les adieux.

Liszt proselytised extensively for Wagner’s music, and regularly supported his future son-in-law financially. His first piano arrangement of Wagner’s music is what is virtually a partition de piano of the mighty Tannhäuser Overture, and he made further works, varying from literal transcriptions to paraphrases, of music from Rienzi; Der fliegende Holländer; Tannhäuser; Lohengrin; Tristan und Isolde; Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg; Der Ring des Nibelungen [Das Rheingold] and Parsifal. We have Liszt to thank for the title which has clung, with Wagner’s approval, to the last scene of Tristan. Of course, this would be the last opera that Liszt heard before his death, and it had been close to his heart from its inception. A short phrase taken from the second act duet introduces a transcription of Isolda’s Love-Death which manages to convey not just Wagner, but Liszt’s total admiration of the music which he thought to be the greatest of its time.

For some inscrutable reason, Liszt subtitled his transcription of the Tannhäuser overture Konzertparaphrase. A paraphrase it most certainly is not, and, with the tiniest exceptions, it proceeds faithfully, bar-for-bar, with Wagner’s score and deserves to be considered alongside Liszt’s transcriptions of the Beethoven Symphonies, the Weber Overtures, the William Tell Overture and the major orchestral works of Berlioz. Uniquely amongst Liszt’s works, the score contains no pedal directions at all, but the performer is instructed to use his discretion in the matter. On the face of it, the job is plainly to attempt an orchestral fulness of sound, and the few directions that one can transfer from parallel passages in Liszt’stranscription of the Pilgrims’ Chorus suggest that one is to paint is broad strokes, and that the brass chords are the important foundation – upper details being of secondary importance. The transcription used to be a very popular warhorse at piano recitals, and it was memorably recorded by the great Benno Moiseiwitsch. Nowadays it is rarely attempted in public, so it is a great pleasure to present it in recital.’

https://youtu.be/wU0lEOJP2z8?si=b4OnYBhZCzL1BLoO

Notes © Leslie Howard, 2025

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2024/12/25/point-and-counterpoint-2024-a-personal-view-by-christopher-axworthy/ https://www.johnleechvr.com/