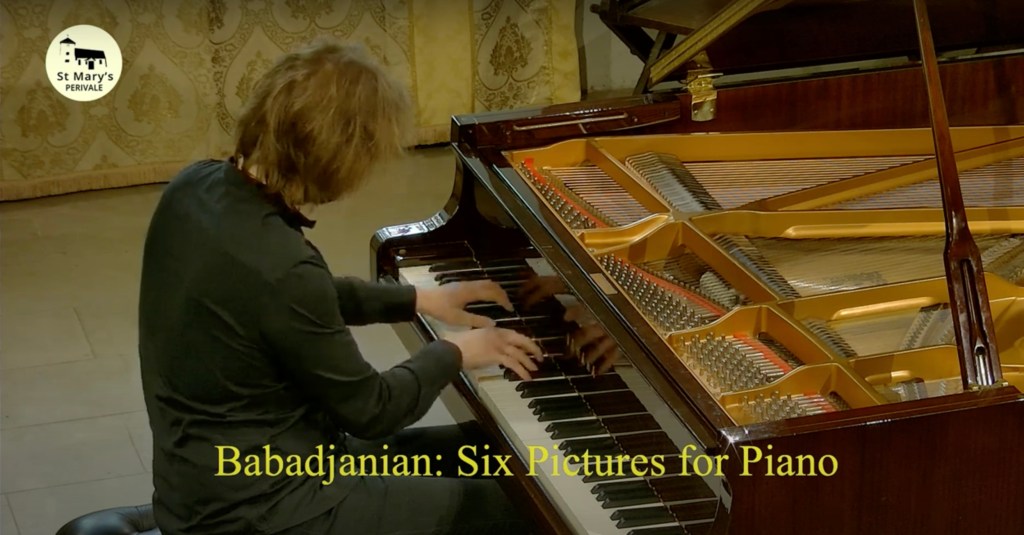

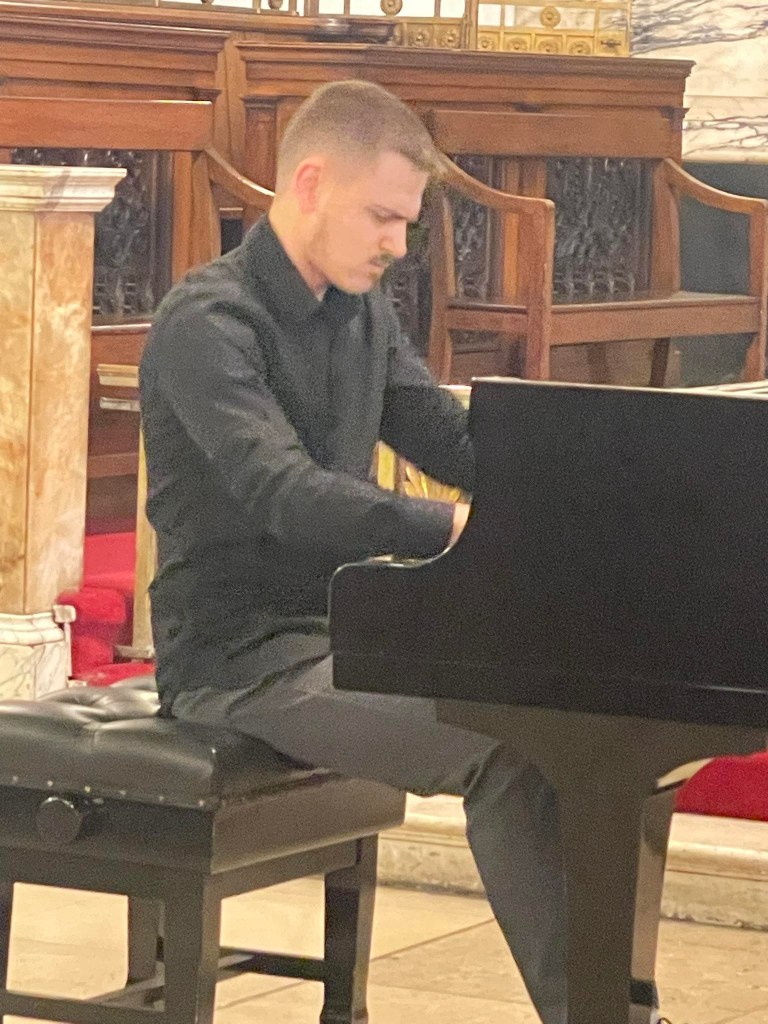

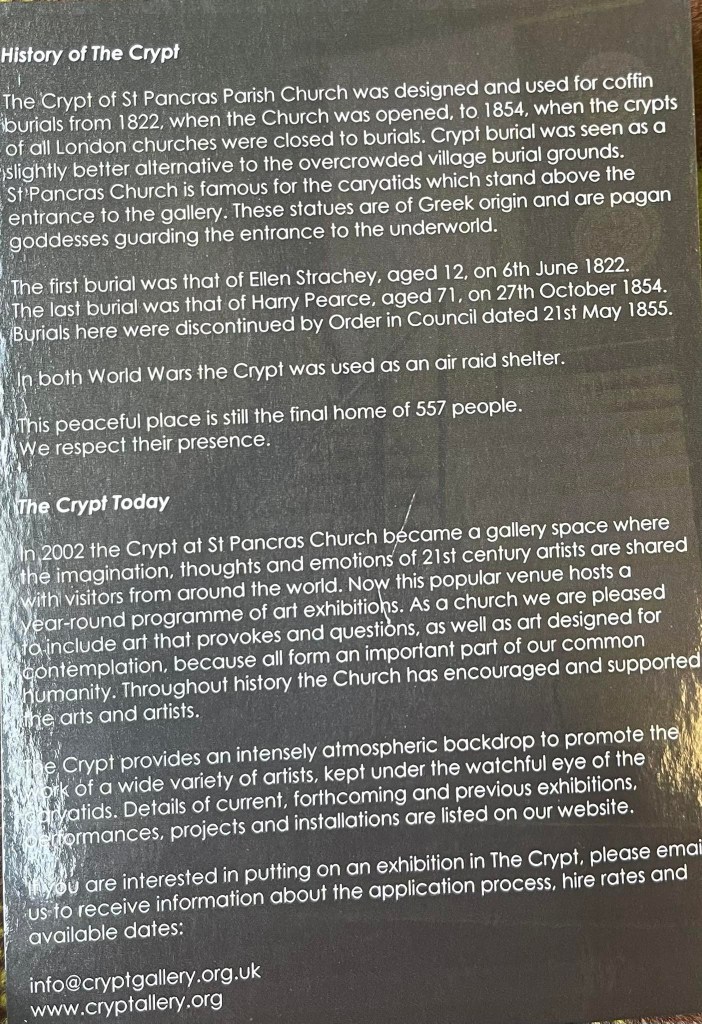

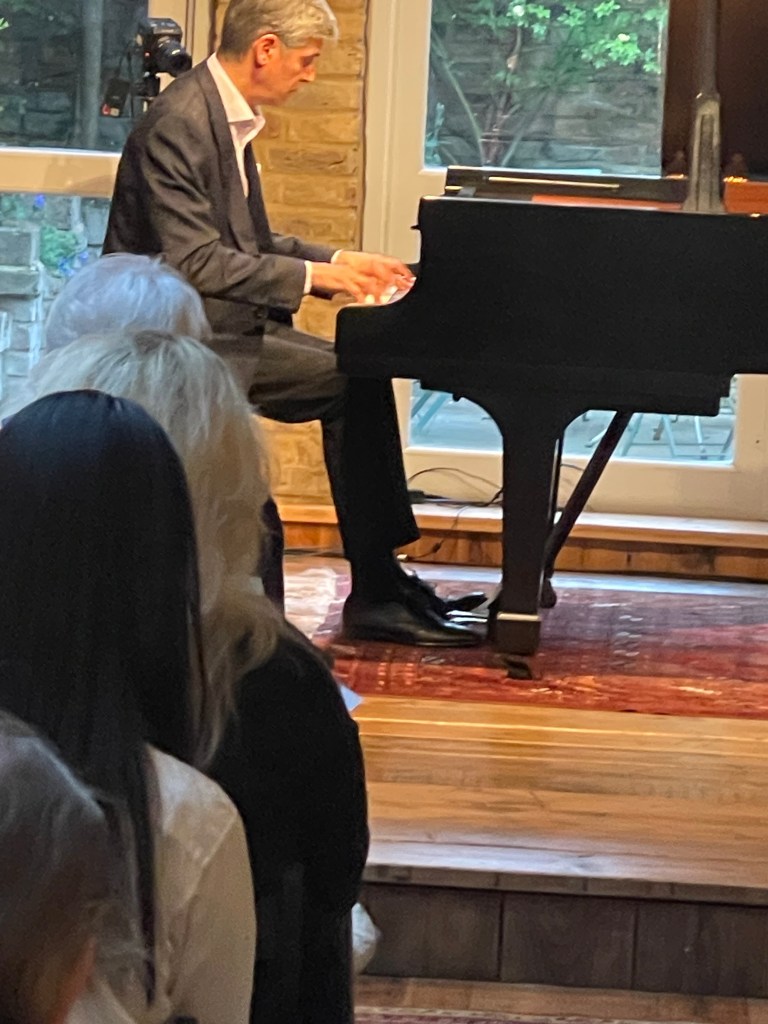

Nice to see Rustem Hayroudinoff back on the concert platform and playing as wonderfully as ever.Playing on Fou Ts’ong’s Concert Grand that now stands so proudly in the Razumovsky Academy that was built and run by the Kogan family with such warmth and generosity .

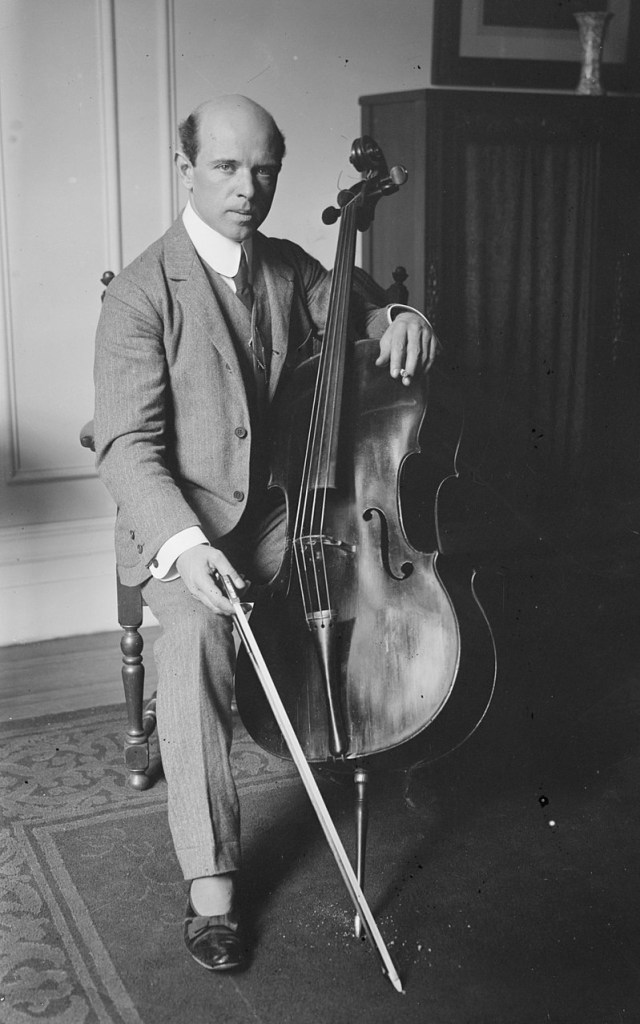

Oleg Kogan the renowned cellist pieced together the bricks and mortar of this chamber music hall of about one hundred seats and it is this love and dedication to real music making that envelopes you as you enter.

Rustem and he were at the Moscow Conservatory together over forty years ago and are now both distinguished professors, Rustem at the Royal Academy, and Oleg until recently at the Guildhall.

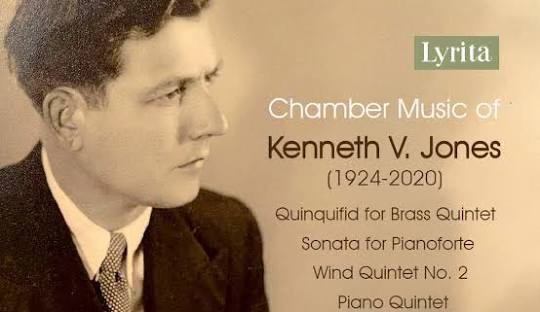

So what better place could there be to celebrate the release of Rustem’s new CD : ‘ Bach &Sons ‘ , that marks his miraculous recovery from a cruel disease that had struck so silently and unexpectedly a few years ago

Rustem Hayroudinoff’s passion for this music is evident in his beautifully curated album, containing some real gems and much that may be new to listeners.

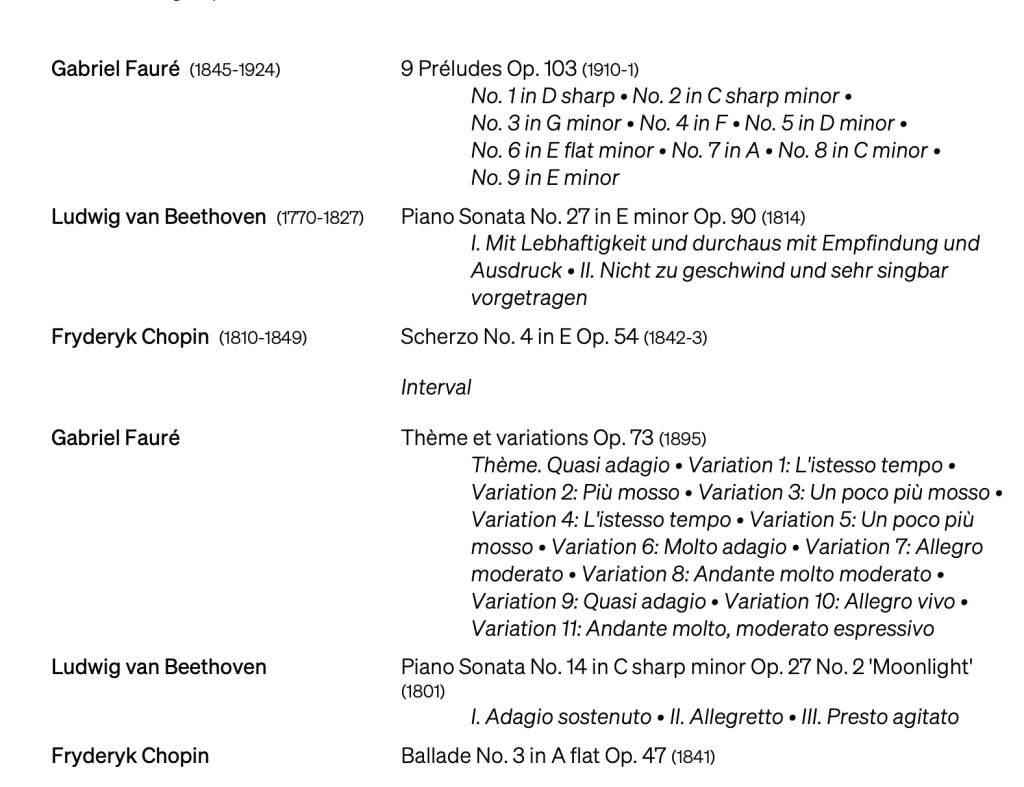

The two parts of the programme showed two completely different pianists with a Schumannesque change of character. The first part was played with the monumental clarity and intelligence of its time that in the second half were translated into the naked passions and seduction also of its time.

The work by ‘Papa’ Bach was followed by two from the musician’s siblings from his vast family of seventeen children.

Bach was indeed prolific, in life as in music, because his life was music and his universal genius is still being unravelled almost three hundred years on.

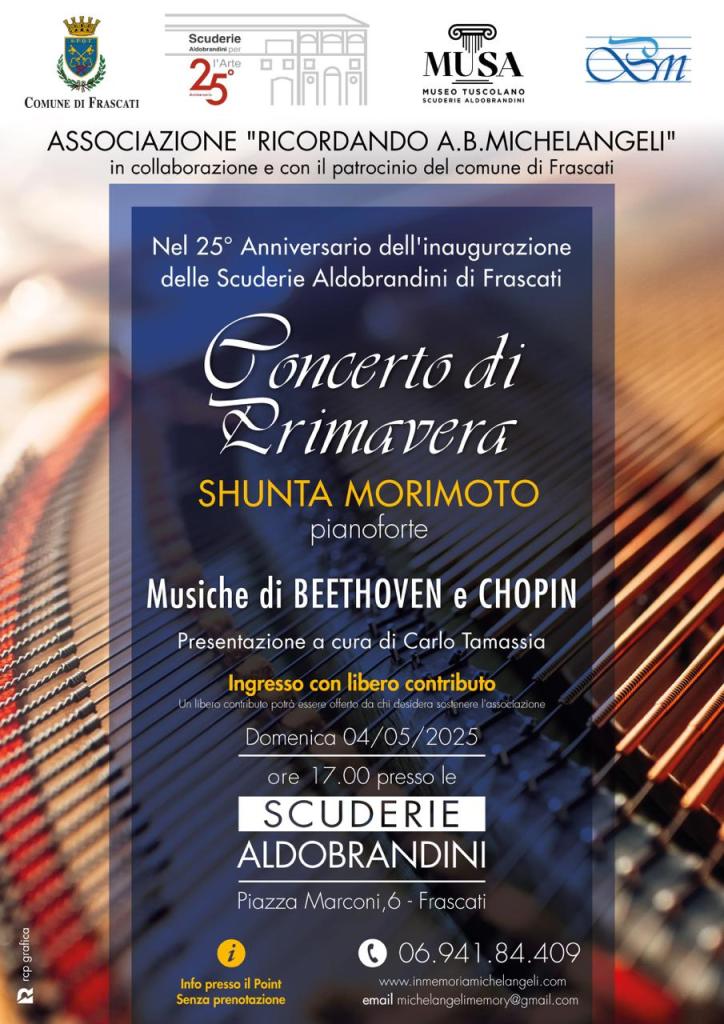

The genius of Chopin too had created a new art form with the discovery of a piano with a ‘soul’. The pedals allowed Chopin to create new sounds and ways of making them that were from then on part of a world of less monumental music making but that of musicians who could turn the sedate ladies of the Parisian salons into a screaming mob trying to take a souvenir home of the artists who could ignite passions they were never aware of before.

Paganini and Liszt were considered the devils in disguise whereas Chopin’s was a more refined subtle seduction of the senses. Tchaikowsky’s turbulent emotional life was taken up by Rachmaninov who although he looked as though he had just swallowed a knife, according to my old teacher Vlado Perlemuter, his music making showed that appearances can be deceptive!

It was these two worlds the Rustem,with transcendental mastery, and with extraordinary musical intelligence ,showed us today.

His chameleonic change of character belied the charmingly reticent introductions to the programme that was unfolding from his ten magnificent fingers. They became a Köthen Baroque Orchestra on one hand, and the sumptuous Philadelphia on the other.

His wife and two children looking on with loving disbelief as this miracle unfolded in public once more.

https://www.gramophone.co.uk/…/i-had-to-tell-my-wife-i……. …..to be continued…………..:

There was a dynamic rhythmic energy to the opening of the J.S Bach English Suite that was to show Rustem’s vision of the monumental Bach that he envisaged. It was played with extraordinary clarity with the pedals only used very sparingly and to signify the change of register. Ornaments added just to add a different colour to the architectural shape of Bach’s mathematical genius. A knotty twine that in Rustem’s masterly hands was not at all knotty as the counterpoints were voices on their own that added up to a magnificent whole.

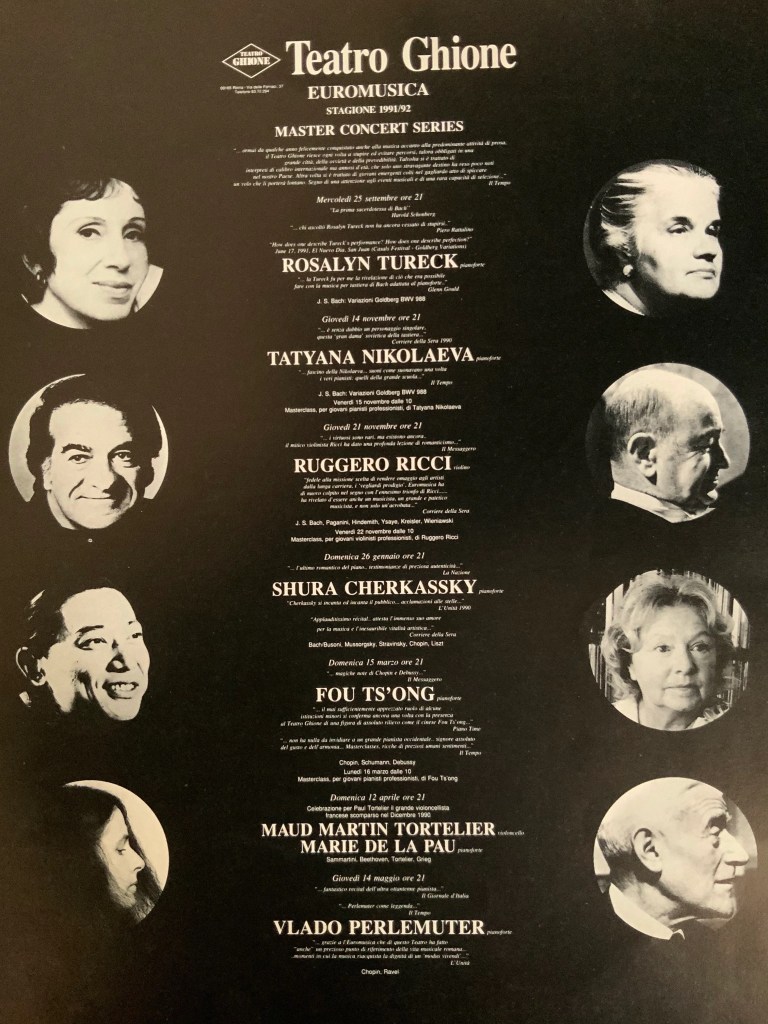

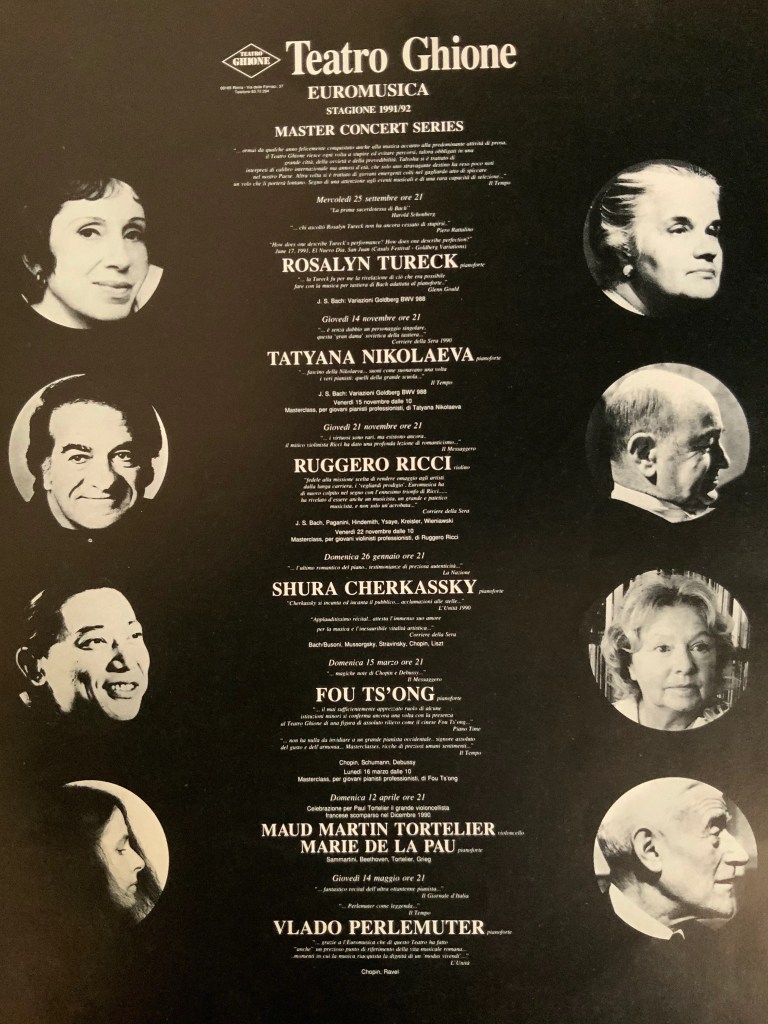

There are at least two schools of thought for the interpretation of Bach on a modern day piano and it was a privilege to invite the two High Priestesses of their day to play the Goldberg Variations for my concert season in Rome. I was much criticised for not having more adventurous programming but to those that could understand there was the monumental Bach of Rosalyn Tureck that was like a rock that was looked up to in awe. And there was the song and the dance of the people of Tatyana Nikolaeva. Added to that, elsewhere, there was Glenn Gould who added his genius in a very individual virtuosistic way.Other pianists like Louis Lortie steer clear of Bach on the modern piano and Andras Schiff prefers to play on the pianos nearer their period.

Rustem chose absolute clarity and rhythmically driven performances that did not preclude the mellifluous beauty he gave to the ‘Allemande’ with very discreet ornaments that embellished without adding any personal emotions.The ‘Courante’ just sprang from his well oiled fingers before the majesty and poignant significance that he brought to the ‘Sarabande’, where he reconciled nobility and delicacy. A crystalline clarity to the first ‘Minuet’ contrasted with the whispered echo effect of the second, with his beguiling ornaments of exquisite charm, before the innocent return of the first Minuet. The ‘Gigue’ was played with chiselled perfection and if it would have been hard to dance to it was in style with Rustem’s magisterial vision that he shared with us.

The Sonata by C.P.E. Bach took me by surprise and was indeed a crazy conflict between Florestan and Eusebius. Extraordinary control that allowed Rustem one moment to play with transcendental velocity and the next with heartrending cantabile. It was as though the fast episodes were merely accompanying a chorale (similar to Chopin’s Third Scherzo op 39). Rustem managed to convey the architectural shape with these quick fire exchanges of extraordinary originality. He brought a restrained and dignified outpouring to the ‘Poco Andante’ with beautifully entwined counterpoints, and a quite extraordinary ‘fingerfertigkeit’ to the antics of the ‘Allegro assai ‘

The Sonata by J.C. Bach was much more mellifluous and Rustem allowed it to flow with clarity and chiselled beauty before the dynamic rhythmic drive of the ‘Presto’ Finale.

After the interval we heard another pianist, that of the great Russian School of breathtaking virtuosity with a kaleidoscope of colour and emotions. This was indeed masterly playing with the beguiling whispered beauty of Rachmaninov’s ‘Lullaby’ played with glistening beauty and the improvised freedom or recreation. Three Etudes -Tableaux were, of course, crowned by the extraordinary nostalgia and majesty of the E flat minor op 39 n. 5, played with passion and ravishing beauty . A sense of balance of orchestral dimensions where the melodic line just rose so radiantly above a surge of emotional power. Adding the E flat prelude op 23 to the C minor was a master stroke as the E flat is one of the most ravishingly romantic of all the preludes with a stream of whispered sounds on which Rachmaninov allows himself to wallow with heartrending emotional impact. The great C minor was by contrast a hurricane of sounds on which the melodic line emerged like an Eagle surveying all that was swirling under foot.

Luckily Ian Jones deputy Head of Keyboard at the RCM reminded Rustem that he still had to play Chopin to complete the programme!

Chopin op 22 that he played with ravishing beauty and scintillating jeux perlé .Also the showmanship of the aristocratic good taste that the teenage Chopin would have demonstrated in the the Parisian Salons that he took by storm. Performances that had Liszt and Schumann at his feet in respect of the Genius that was in their midst. ‘Hats off ,Gentlemen, a Genius !’ wrote Schumann in his journal of the day.

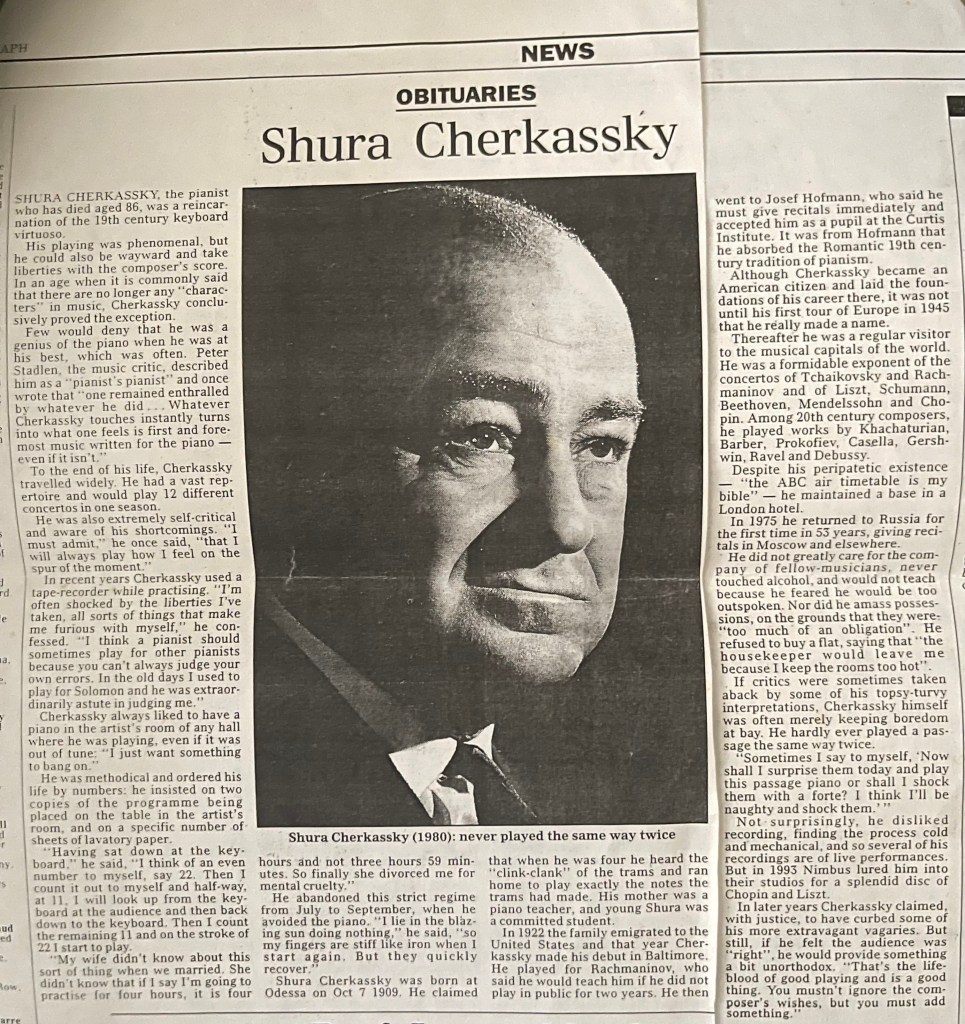

A encore of the ‘Polka of WR’ by Rachmaninov was played with the charm and style of another age and reminded me of the times that Cherkassky would end his recitals with this very piece played with the same tantalising charm that Rustem offered as a thank you to us today .

In the Summer 2021 The Razumovsky Trust purchased a marvellous Steinway D Concert Grand Piano for the Razumovsky Academy.

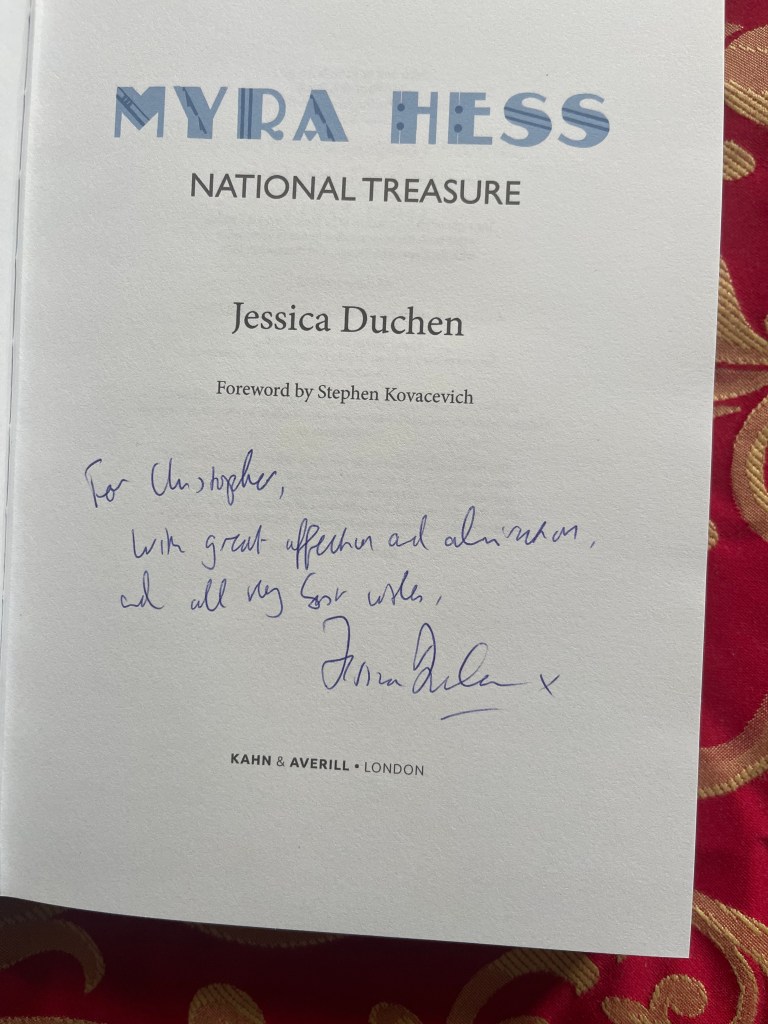

The Trustees are very grateful to the many Friends of the Razumovsky Trust who contributed generously to our Steinway D Piano Fund.This fabulous instrument belonged for many years to the legendary Chinese pianist Fou Ts’ong and his wife Patsy Toh. The distinguished French pianist François-Frédéric Guy said Fou had been his “mentor and a musical father”. “His Debussy, Chopin and Mozart remain legendary.”The renowned Chinese pianist Lang Lang described Fou Ts’ong as “a truly great pianist, and our spiritual beacon”. “Master Fou was a great artist…His understanding of music was unique.”We are immensely grateful to Nigel Polmear who introduced us to this instrument. Nigel suggested we invite Ulrich Gerhartz to advise on the best ways to preserve its beautiful qualities whilst at the same time ensuring that it is ready to serve Razumovsky Academy as a hardworking stage piano.

Ulrich Gerhartz, following initial examination of the instrument, suggested a comprehensive programme of servicing, both at Steinway Hall London’s workshop, and on-site at the Razumovsky Academy. Following completion of works by Ulrich, the rehearsals and recordings have resumed. “Ulrich’s work on the instrument was magical.” (Oleg Kogan).Our Chairman Sir Bernard Rix came to the Razumovsky Academy to meet Ulrich Gerhartz during the works. Our dear friend Julius Drake, who came to rehearse here with singers Alice Coote and Ian Bostridge, commented on the piano: “Absolutely marvellous!

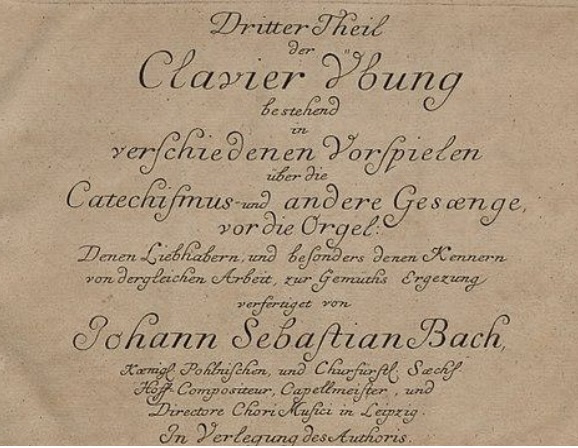

21 March 1685 Eisenach 28 July 1750 (aged 65) Leipzig

The English Suites, BWV 806–811, are a set of six suites by Johann Sebastian Bach for harpsichord (or clavichord) and generally thought to be the earliest of his 19 suites for keyboard (discounting several less well-known earlier suites), the others being the six French Suites (BWV 812–817), the six Partitas (BWV 825-830) and the Overture in the French style (BWV 831). They probably date from around 1713 or 1714 until 1720.

Suite No. 3 in G minor, BWV 808

Prelude – Allemande – Courante – Sarabande – Gavotte 1 – Gavotte 11 Gigue

The Sonata in F sharp minor H37 (Wq52/4) by C.P.E Bach dates from 1744. The most remarkable movement is the opening Allegro, built on a contrast between fantasia and lyric passages. In comparison to this unusual opening movement, the following Poco andante, in D major, is a study in restrained elegance. The finale is again in binary form featuring dotted rhythms and occasional sudden rests setting off dramatic harmonic progressions. Allegro – Poco Andante – Allegro assai

The genius of Johann Sebastian Bach often overshadows the achievements of his four prodigiously talented sons, all of whom played a crucial role in further advancing music’s development during the 18th century. Johann Christian, the youngest, was indeed among the most pivotal composers of his day, his move to Italy in 1755 precipitating a noticeable change in style that, known as the galant, looked forward to the soon-to-emerge Classical period.

J.C. Bach was the first to champion the fortepiano in concert, and by the time he came to write his Six Sonatas Op.17, the instrument was well on its way to dominance. Following on from the Six Sonatas Op.5 , the works reveal the composer’s multifaceted skills, displaying the widest possible range of compositional manners and characters –One of J.C. Bach’s many admirers was Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, and it is highly likely that these works were among those played to the young prodigy when he visited London in the 1760s, where the German composer was then living. They comprise a set truly befitting of a composer who would later became music master to the English royal family, revealing how, in the realm of keyboard virtuosity, J.C. Bach was every bit his father’s son. Given J.C. Bach’s influence on Mozart, it should come as little surprise that the sonatas of Op.17 are almost stylistically interchangeable with those of the Salzburg genius.Sonata in A op.17 n.5 Allegro – Presto