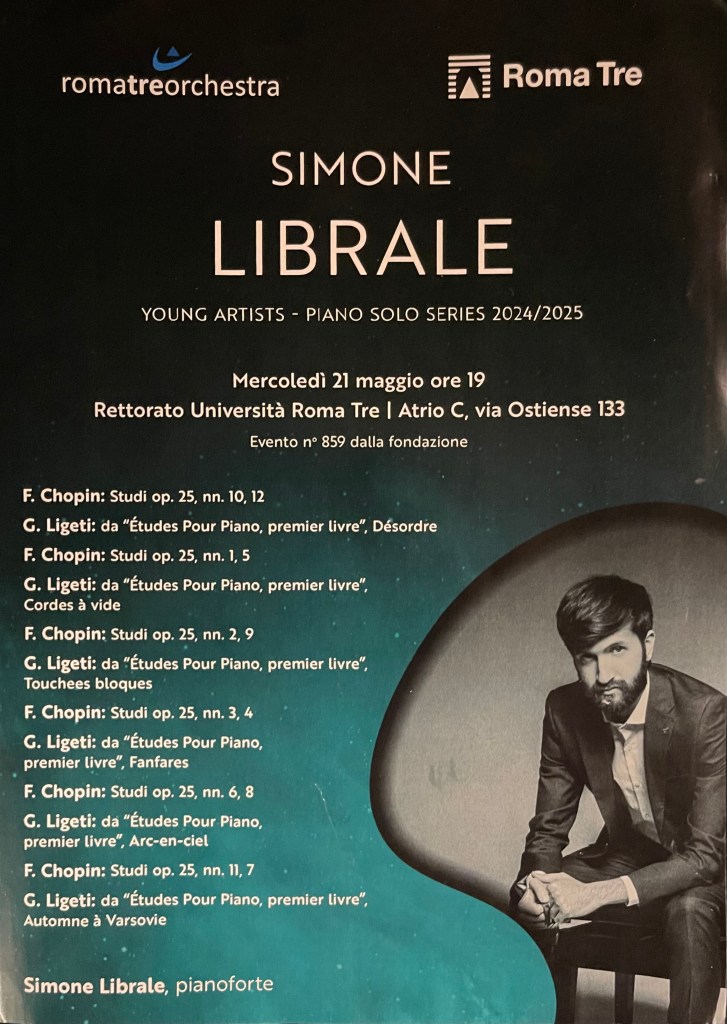

Mercoledì 21 maggio ore 19, Rettorato Università Roma Tre

Simone Librale, Young Artists Piano Solo Series 2024 – 2025

Chopin and Ligeti combine.

Worlds apart but both were the technical innovators of their time, as Simone Librale demonstrated at Roma 3 University in the last concert of their official season.

A remarkable feat of memory and intellectual curiosity allowed Simone to show us the technical innovations of Ligeti with his studies Book 1.

Contrasting them with the Chopin studies op 25 and alternating the different worlds with an astonishing ease and clarity

It was this clarity that he brought to the extraordinary rhythmic juxtapositions in Ligeti.

With Chopin he chose a freer more improvised approach but it was obvious that Simone’s heart lay elsewhere.

A quite extraordinary brain that can decipher Ligeti’s diabolically innovative inventions with an astonishing facility .

A technique that uses parts of a piano that neither Liszt,Chopin, Thalberg , Czerny or even Alkan had ever dreamt of.

Simone’s remarkable brain could cope in a masterly way with Ligeti’s gleeful rhythmic juxtapositions practically without pedal. Pedal only added where Ligeti allows himself to wallow in sonorous vibrations rather than get twisted in knotty twine.

It was the intellectual architecture that did not allow much scope for any personal intervention but ‘merely’ to state the facts on the page, which was no mean feat. His diabolical ‘Désordre’ coming after Chopin’s Octave and Ocean Etudes was like a mad man’s ranting. It was a composer determined to eliminate any personal interventions or unnecessary distortions.

It was here from the very first notes of Ligeti versus Chopin that the duel personality of Simone became alarmingly apparent .

Where in Ligeti there had been no room for any rhythmic distortions, in Chopin Simone allowed himself a freedom that distorted the equally important architectural structure .

Whereas in Ligeti Simone’s technical mastery had never been in doubt in Chopin one began to feel that he had entered a world of which he was an obedient observer and not a fervent admirer.

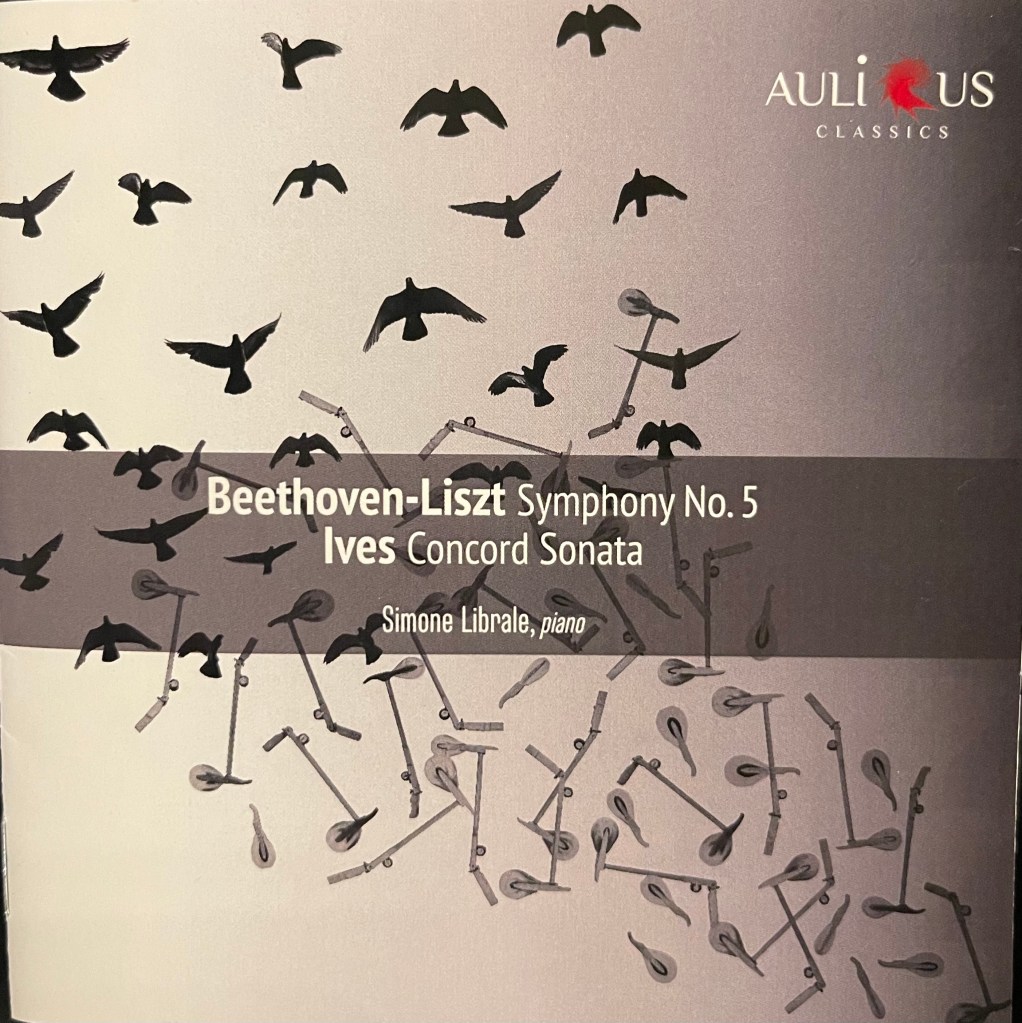

I remember Simone’s masterly account of the ‘Concord’ Sonata by Ives broadcast live on the RAI and see on his latest CD he has combined it with Liszt’s innovative transcription of Beethoven’s Fifth. In between Ives revolutionary cacophany Beethoven 5th makes a startling entrance together with many other cameo appearances in a work that astonished and admonished an audience at the start of the twentieth century. https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2020/03/12/aimards-hammerklavier-and-concord-sonatas-in-london/

I had just heard it in London from Emanuil Ivanov who played the remarkable Ives Sonata which is gradually taking its place in the repertoire 125 years on ! Only Bach and Schubert were to suffer the same fate!

Simone is like a Roger Woodwood character who took London by storm in the 70’s with three hour programmes that ranged from Beethoven’s ‘Hammerklavier’ to the Baraqué sonata for piano ,chain and hammer. A pianist who like Simone is interested in the intellectual and cerebral rather than style and tradition.

Listening to Simone’s stimulating juxtaposition I could not help feeling that a worthy experiment could be to play Ligeti like Chopin and Chopin like Ligeti as it might illuminate both without separating the two worlds so definitively as Simone did today.

The whole point of the technical innovations of Chopin was the invention of the pedal, which Anton Rubinstein described as the ‘soul’ of the piano. It allowed Liszt and Thalberg to invent the three handed piano technique where a melody could be floated in the middle of the keyboard , by a sleight of hand ,whilst notes were flying all around.

Chopin of course was the greatest innovator who with the use of the pedal , very precisely noted in the score and too often overlooked, allowed a sense of touch and poetic fantasy that had not been possible before. Beethoven too would use the pedal to create very special effects that are too often overlooked !

Ligeti seems to break away from the freedom that the pedal could give and puts the performer in a straight jacket where there is no room for manouver.

There are moments in Ligeti , though, when like Berio he experiments with sound as in ‘Cordes à vides’ or even ‘Arc-en – ciel’ ( that interestingly Nikola Meeuwsen had played as an encore here before reaching the final of the Queen Elisabeth Competition this week, where he is actually locked up for a week to learn a commissioned 21st century concerto for the final round ).

It was here that Simone’s remarkable precision and digital and cerebral mastery did not contemplate a depth of sound and a weight where in every key there are infinite gradations of tone. When Simone was playing just black and white it showed an extraordinary cerebral dexterity but when a more intense palette of sounds was needed he lost his architectural sense of control .

Simone offered an encore after an ovation for such a ‘tour de force’, allowing us to see another side of this remarkable artist. A simple ‘song without words’ was allowed to unfold with beauty and subtlety and was where Simone’s two conflicting worlds were finally united with Wagner’s ‘In das Album der Fürstin Metternich’ WWV 94

Simone Librale, ha studiato pianoforte all’ISSM “Pietro Mascagni” di Livorno sotto la guida di Daniel Rivera e Maurizio Baglini, conseguendo il diploma accademico con lode e menzione d’onore. Specializzatosi nel repertorio moderno e contemporaneo, ha proseguito gli studi presso l’Accademia di Musica di Pinerolo con Emanuele Arciuli e Ralph van Raat. Ha debuttato come solista con la Roma Tre Orchestra nel 2020, eseguendo il “Mozart Project” sotto la direzione di Sieva Borzak. Ha partecipato a festival di rilievo come il Bari Piano Festival, il Festiva Liszt e il Festival Luciano Berio. Nel 2022, ha eseguito la Quinta Sonata di Salvatore Sciarrino al Teatro Verdi di Pordenone, ottenendo il plauso del compositore stesso. Nel 2023, ha partecipato alla prima mondiale di “11.000 Saiten” di Georg Friedrich Haas al Bolzano Festival Bozen. Nel 2024, ha tenuto un recital trasmesso su Rai Radio3 per “I Concerti al Quirinale,” eseguendo la Sonata n.2 di Charles Ives, ricevendo ampi consensi. Ha frequentato masterclass con Pierre-Laurent Aimard, Louis Lortie e Andrea Lucchesini.

Below is a fascinating discussion with Maurizio Baglini and Simone Librale

György Ligeti 28 May 1923 Transylvania Romania – 12 June 2006 (aged83) Vienna, Austria

The Hungarian composer Gyorgy Ligeti composed a cycle of 18 études for solo piano between 1985 and 2001. They are considered one of the major creative achievements of his last decades, and one of the most significant sets of piano studies of the 20th century, combining virtuoso technical problems with expressive content, following in the line of the études of Chopin,Liszt,Debussy and Scriabin but addressing new technical ideas as a compendium of the concepts Ligeti had worked out in his other works since the 1950s. Pianist Jeremy Denk wrote that they “are a crowning achievement of his career and of the piano literature; though still new, they are already classics.”.

There are 18 études arranged in three books or Livres: six Études in Book 1 (1985), eight in Book 2 (1988–1994), four in Book 3 (1995–2001). Ligeti’s original intention had been to compose only twelve Études, in two books of six each, on the model of the Debussy Études, but the scope of the work grew because he enjoyed writing the pieces so much.] Though the four Études of Book 3 form a satisfying conclusion to the cycle, Book 3 is in fact unfinished—Ligeti certainly intended to add more, but was unable to do so in his last years, when his productivity was much reduced owing to illness. The Études of Book 3 are generally calmer, simpler, and more refined in technique than those of Books 1 and 2.

The titles of the various études are a mixture of technical terms and poetic descriptions. Ligeti made lists of possible titles and the titles of the individual numbers were often changed between inception and publication. He often did not assign any title until after the work was completed.

Book 1

- Désordre. Molto vivace, vigoroso, molto ritmico, = 63A study in fast polyrhythms moving up and down the keyboard. The right hand plays only white keys while the left hand is restricted to the black keys. This separates the hands into two pitch-class fields; the right hand music is diatonic, the left hand music is pentatonic. This étude is dedicated to Pierre Boulez

- Cordes à vide. Andantino rubato , molto tenero, = 96Simple, almost Satie-esque chords become increasingly complex. These chords are built primarily from fifths, reminiscent of open strings, hence the title. This étude is also dedicated to Pierre Boulez.

- Touches bloquées. Vivacissimo, sempre molto ritmico – Feroce, impetuoso, molto meno vivace – Feroce, estrepitoso – Tempo ITwo different rhythmic patterns interlock. One hand plays rapid, even melodic patterns while the other hand ‘blocks’ some of the keys by silently depressing them. This is the last étude Ligeti dedicated to Boulez.

- Fanfares. Vivacissimo, molto ritmico, = 63, con alegria e slancioMelody and accompaniment frequently exchange roles in this polyrhythmic study which features aksak-influenced rhythms and an ostinato in 88 time, dividing the bar of 8 eighth notes into 3+2+3. This ostinato is also used in the second movement of Ligeti’s Horn Trio ] This étude is dedicated to Volker Banfield .

- Arc-en-ciel. Andante con eleganza, with swing, ca. 84The music rises and falls in arcs that seem to evoke a rainbow. This étude is dedicated to Louise Sibourd.

- Automne à Varsovie. Presto cantabile, molto ritmico e flessibile, = 132Its title, Autumn in Warsaw, refers to the Warsaw Autumn, an annual festival of contemporary music. Ligeti referred to this étude as a “tempo fugue”. A study in polytempo, it consists of a continuous transformation of the initial descending figure – the “lamento motif” as Ligeti called it – involving overlapping groups of 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, ending up at the bottom of the keyboard. This étude is dedicated to Ligeti’s Polish friends.

From 1985 to 2001, Ligeti completed three books of Études for piano (Book I, 1985; Book II, 1988–94; Book III, 1995–2001). Comprising eighteen compositions in all, the Études draw from a diverse range of sources, including gamelan. African polyrhythms, Béla Bartók,Conlon Nancarrow,Thelonius Monk and Bill Evans . Book I was written as preparation for the Piano Concerto, which contains a number of similar motivic and melodic elements. Ligeti’s music from the last two decades of his life is unmistakable for its rhythmic complexity. Writing about his first book of Piano Études, the composer claims this rhythmic complexity stems from two vastly different sources of inspiration: the Romantic-era piano music of Chopin and Schumann and the indigenous music of sub- Saharan Africa.

The difference between the earlier and later pieces lies in a new conception of pulse. In the earlier works, the pulse is something to be divided into two, three and so on. The effect of these different subdivisions, especially when they occur simultaneously, is to blur the aural landscape, creating the micropolyphonic effect of Ligeti’s music.In 1988, Ligeti completed his Piano Concerto, writing that “I present my artistic credo in the Piano Concerto: I demonstrate my independence from criteria of the traditional avantgarde, as well as the fashionable postmodernism.” Initial sketches of the Concerto began in 1980, but it was not until 1985 that he found a way forward and the work proceeded more quickly. The Concerto explores many of the ideas worked out in the Études but in an orchestral context.