As Dr Mather said today it is unusual to find a recital of just Beethoven Sonatas with the exception of the last trilogy. I remember artists such as Serkin, Arrau ,Foldes and Kempff playing recitals of four Beethoven sonatas. Occasionally we would get a cycle of all 32 Sonatas from Arrau, Barenboim and these days from Igor Levitt and Boris Giltburg. It is rare to hear the early Sonatas in concert programmes, yet they are some of the most startlingly original works, where youthful elegance and beauty are starting to feel the eruptions that are in Beethoven’s soul. The real revelations or revolutions are in the slow movements of op 2 n. 3, op 7 and op 10 n.3 where one can see the genius of Beethoven taking the form from his teacher Haydn but adding a density and profundity that was not part of the eighteenth century. where elegance and refined formality was the norm.

Cristian has started at the top having just recorded the last three Sonatas dedicated to his father Sandu Sandrin’s memory. And only now I hear him play from the bottom, and judging from his masterly playing of these early op 2 Sonatas and the Trilogy, I hope he will now fill in that vast gap which is the map of Beethoven’s life in 32 steps.

There was an elegance and exhilaration to the first of Beethoven’s 32 sonatas with a clarity and always beauty of sound. The hand of Cristian paints the same beauty as the sound he is creating and he has a noticeable way of allowing his hands to look at the keys like a bird eyeing their prey. An extraordinarily natural way to play where everything he plays is like swimming in water with beautiful horizontal movements of complete relaxation. I have often remarked on his trills, where he holds his arm up high and lets the fingers just vibrate over the keys. It was this simple beauty added to his intelligence of following all the indications left by the composer, not only on the printed page but also within the spaces, which are the meaning behind the notes. An ‘Adagio’ of refined subtle beauty and purity, followed by the elegance of the ‘Minuet’ with its beautifully flowing ‘Trio’. The ‘Prestissimo’was played with controlled brilliance and clarity with the opening bubbling over like water boiling at 100 degrees and then bursting into a melodic outpouring of noble beauty. I remember Serkin playing this with fearless abandon and hysterical intensity which was like an electric shock. Serkin was unique and Cristian played with the intensity and intelligence of Arrau which was controlled but still of great drive and brilliance.

The very capricious opening of op n 2 n. 2 became ever more serious and demanding with its burning question and answer.There was an orchestral colour to the ‘Largo’ with its pizzicato accompaniment to the nobility and radiance of the melodic line. Delicate playfulness to the ‘Scherzo’ contrasting with the flowing passion of the ‘Trio.’ The swooping flourish of the Rondò played with charm and restraint before the ‘Sturm und Drang’ of the central episode, contrasting always with the elegant entry of the rondò theme with flourishes ever more prolonged. Played with masterly simplicity and radiance where Beethoven was allowed to speak for himself without any extraneous interventions from the performer.

Op 2 n. 3 is notorious for its opening double thirds and I have seen Nikita Lukinov play it even with a helping hand from his left ! Cristian played it with gentle elegance with one hand and it was this return of the opening elegant declaration that was so touching after the dynamic outbursts of a Beethoven who was already feeling the vast canvas that was opening up from his heritage. Full robust sounds where every note had its just weight but without any hardness or brittle percussive brilliance.There was beauty too, with Beethoven’s beautiful mellifluous outpouring of Schubertian proportions. An architectural shape to this, the longest first movement of these first three sonatas. This is the first really important Sonata that became a favourite of the great pianists such as Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli and Claudio Arrau.There was a timeless beauty to an ‘Adagio’ of extraordinary poignancy and importance demonstrating the pupil breaking out of the shell of his teacher. There was a rhythmic insistence to the ‘Scherzo’ and an enviable sweep to the Trio.The ‘Allegro’ was played with infectious dance rhythm where the chords were played with a lightness and elegance that was quite remarkable for its shape and beauty. There was dynamic drive too that brought us to a tumultuous ending, but always within the sound world of Beethoven’s architectural mastery.

Born into a family of musicians from Bucharest, Cristian Sandrin has been surrounded by classical music all his life. His frequent visits to the historic Romanian Atheneum concert hall and his attendances at the prestigious Enescu Festival shaped his musical aspirations from early childhood. Years later, he would have his own debut at the Atheneum at the age of 13. Cristian is especially devoted to the Classical and Romantic repertoire. His passion for Mozart’s piano concertos led him to direct from the keyboard several concertos during Summer Festivals at the Royal Academy of Music, as well as for the official opening of the Angela Burgess Recital Hall. From 2018–2020 he was privileged to tour the UK as an artist of the Countess of Munster Recital Scheme. Additionally, He is a scholarship holder of the Imogen Cooper Music Trust benefiting from her unique one-to-one guidance and mentorship since 2017. He graduated in 2019 from the Royal Academy of Music, receiving a DipRAM, MMus later being part of the prestigious Advanced Diploma programme.

In 2023 he was invited to become the co-Artistic Director of the much-admired Kettner Concerts which are held in the David Lloyd George Hall of the National Liberal Club, Rachmaninov’s favourite London recital room and the venue where he performed his European farewell concert. In 2021 Cristian travelled to Romania for his debut with the acclaimed George Enescu Philharmonic performing Mozart’s K 503 Piano Concerto in C major at the country’s foremost music venue: The Romanian Atheneum.Since 2020, Cristian has performed challenging solo programmes including Beethoven’s last three sonatas and Bach’s Goldberg Variations in famous venues across Europe from Berlin’s Konzerthaus, the Radio Hall in Bucharest to London’s LSO St Luke’s and Holywell Music Room Oxford, Sinfonia Smith Square and Sala Puccini in Milan. In July 2025 Cristian will have his debut at Beethovenhaus in Bonn, Germany.

His debut CD Correspondances (Antarctica Records 2022) featuring music by Ravel, Enescu and Cyril Scott has been highly acclaimed in Europe and accross the Atlantic: the German Magazine Piano News selected it as the CD of the Month whilst the American Record Guide named it “the highlight of this month’s listening. Cristian’s performances have been broadcast on major radio and TV stations in Europe and Canada, from Bayerische Rundfunk, to Rai Tre, Radio France Musique, Radio Romania Muzical and Stingray Classica.

Born in Bonn Baptised 17 December 1770. Died. 26 March 1827 (aged 56) Vienna

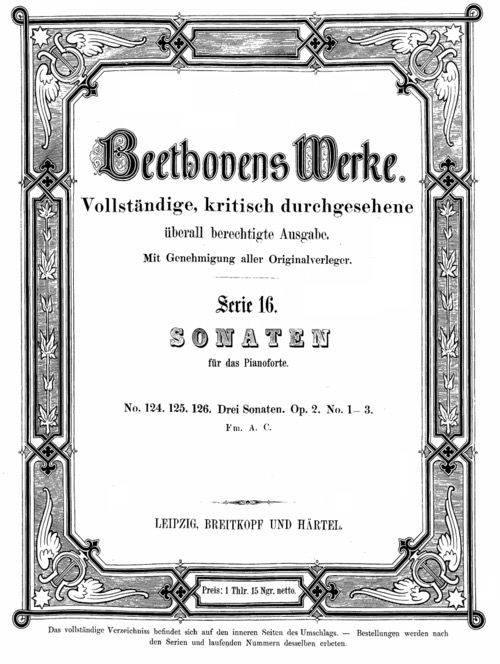

Cover of 1862 edition of Beethoven’s first three piano sonatas (Breitkopf & Härtel)

The conventional first period began after Beethoven’s arrival in Vienna in 1792. In the first few years, he seems to have composed less than he did at Bonn, and his Piano Trios, op.1 were not published until 1795. From this point onward, he had mastered the ‘Viennese style’ (best known today from Haydn and Mozart ) and was making the style his own. His works from 1795 to 1800 are larger in scale than was the norm (writing sonatas in four movements, not three, for instance); typically he uses a scherzo rather than a minuet and trio ; and his music often includes dramatic, even sometimes over-the-top, uses of extreme dynamics and tempi and chromatic harmony. It was this that led Haydn to believe the third trio of Op.1 was too difficult for an audience to appreciate.

He also explored new directions and gradually expanded the scope and ambition of his work. Some important pieces from the early period are the first and second symphonies, the set of six string quartets op.18 , the first two piano concertos, and the first twenty piano sonatas, including the famous Pathétique sonata, Op. 13.Beethoven’s earlier preferred pianos included those of Johann Andreas Stein ; he may have been given a Stein piano by Count Waldstein. From 1786 onwards there is evidence of Beethoven’s cooperation with Johann Andreas Streicher , who had married Stein’s daughter Nannette. Streicher left Stein’s business to set up his own firm in 1803, and Beethoven continued to admire his products, writing to him in 1817 of his “special preference” for his pianos. Among the other pianos Beethoven possessed was an Érardpiano given to him by the manufacturer in 1803. The Érard piano, with its exceptional resonance, may have influenced Beethoven’s piano style – shortly after receiving it he began writing his Waldstein Sonata – but despite initial enthusiasm he seems to have abandoned it before 1810 when he wrote that it was “simply not of any use any more”; in 1824 he gave it to his brother Johann. In 1818 Beethoven received, also as a gift, a grand piano by John Broadwood & Sons. Although Beethoven was proud to receive it, he seems to have been dissatisfied by its tone (a dissatisfaction which was perhaps also a consequence of his increasing deafness), and sought to get it remodelled to make it louder. In 1825 Beethoven commissioned a piano from Conrad Graf, which was equipped with quadruple strings and a special resonator to make it audible to him, but it failed in this task. Beethoven wrote 32 mature piano sonatas between 1795 and 1822. (He also wrote 3 juvenile sonatas at the age of 13 and one unfinished sonata , WoO. 51.) Although originally not intended to be a meaningful whole, as a set they comprise one of the most important collections of works in the history of music.Hans von Bülow called them “The New Testament ” of piano literature (Johann Sebastian Bach’s The Well-Tempered Clavier being “The Old Testament “).

Beethoven’s piano sonatas came to be seen as the first cycle of major piano pieces suited to both private and public performance. They form “a bridge between the worlds of the salon and the concert hall”.[2] The first person to play them all in a single concert cycle was Hans von Bülow; the first complete recording is Artur Schnabel’s for His Master’s Voice.

The first three sonatas, written in 1782–1783, are usually not acknowledged as part of the complete set of piano sonatas because Beethoven was 13 when they were published.

- WoO 47: Three Piano Sonatas (composed 1782–3, published 1783)

- Piano Sonata in E flat major

- Piano Sonata in F minor

- Piano Sonata in D major

Beethoven’s early sonatas were highly influenced by those of Haydn and Mozart. Piano Sonatas No. 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 11, 12, 13, and 15 are four movements long, which was rather uncommon in his time.

- Opus 2: Three Piano Sonatas (1795)

- Piano Sonata n. 1 F minor

- Piano Sonata n. 2 in A major

- Piano Sonata n. 3 in C major

After he wrote his first 15 sonatas, he wrote to Wenzel Krumpholz, “From now on, I’m going to take a new path.” Beethoven’s sonatas from this period are very different from his earlier ones. His experimentation in modifications to the common sonata form of Haydn and Mozart became more daring, as did the depth of expression. Most Romantic period sonatas were highly influenced by those of Beethoven. After his 20th sonata, published in 1805, Beethoven ceased to publish sonatas in sets and published all his subsequent sonatas each as a single whole opus. It is unclear why he did so.