As Royal College of Music 2023/24 Benjamin Britten Piano Fellow, Thomas Kelly is no stranger to London’s stages, having performed the dazzling piano cadenzas in the RCM’s packed performance of Messiaen’s Turangalîla at the Royal Festival Hall last summer.

For this programme, Thomas Kelly performed a solo recital of three extraordinary works, two of them arranged by Busoni – famed for his fiendishly challenging and richly textured transcriptions. Based on Lutheran chorales, Brahms’ 11 Chorale Preludes were the last composition he ever completed. The tenth is a piece of brooding profundity, reflecting Brahms’ grief for the recent loss of his friend, Clara Schumann – who was also the dedicatee of Robert Schumann’s heartfelt First Piano Sonata, while Liszt’s Fantasy and Fugue encompasses grandeur and devout meditation.

Johannes Brahms 1833-1897 Chorale Prelude ‘Herzlich tut mich verlangen’ Op. 122 No. 10

(arranged by Ferruccio Busoni)

Robert Schumann 1810-1856 Piano Sonata No. 1 in F sharp minor Op. 11

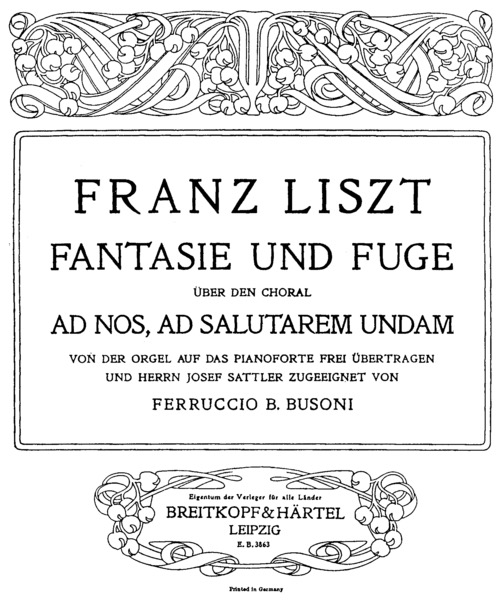

Frank Liszt 1811-1886 Fantasy and Fugue on the chorale ‘Ad nos,ad salutarem undam’ S 259 ( arranged by Ferruccio Busoni)

My second concert this morning was the Britten Fellow Thomas Kelly at the Wigmore Hall .

Hot footing it from my old Alma Mater and Ivanov’s monumental performance of the Concord Sonata I find myself transported to another world, that of the Golden Age of piano playing.

Strangely enough they are the two sides of Busoni, who was the continuation of the prophetic genius of Liszt, who besides being the greatest showman the world has ever known was a prophetic genius who could forge the path into the future .

‘Unconventional’, Emanuil described Ives, but isn’t that just the ingredient where genius is born?

Busoni was a monumental figure whose transcriptions became recreations and his own works looked so far into the future that there are very few that dare to tread that path ,even today.

One such pianist was John Ogdon who like all true geniuses are consumed far faster than ordinary mortals .

Ogdon coming under the influence of Gordon Green who was a disciple of Egon Petri who was a disciple of Busoni, would exhort his many illustrious students to discover the world of Busoni. Stephen Hough on the other hand chose the road of the virtuoso Busoni and the celebration of the piano of the nineteenth century, when after adding a ‘soul’ to the piano it became a complete orchestra.

Pianists became magicians that could turn a wooden box of hammers and strings into a magic box where dreams could come true.

Genius is a hard word to define ( how insufficient words can be when it becomes apparent that music speaks louder than words).

Ogdon was certainly a phenomenon, a genius ,as he was born with a mind and fingers that knew no limits and could embrace the monumental works of Busoni and many of the most complex works in the piano repertoire,as only the master himself could have done .

Thomas Kelly I had heard five years ago at the Joan Chissell Schumann competition at the Royal College and I was immediately bowled over by the sound he made and the fact that he seemed made to sit at the piano. He and his mentor Andrew Ball walking out of the hall together after a monumental performance of Schumann’s Carnaval passed through my mind as I listened mesmerised by a piano genius today .

Genius is not easy to live with as the Alexeev’s and Vanessa Latarche well know. Vanessa had taken over the post of Head of Keyboard from an already ailing Andrew Ball and in a certain sense inherited his pride and joy, Thomas Kelly.

There was magic in the air as Tom opened with the murmured benediction of Brahms /Busoni, where the chorale emerged from the sumptuous sounds of reverence that were wafting into the rarified air that was emanating from Toms magic fingers .

Schumann grew out of these sounds as Brahms bequeathed his halo to Schumann . One of Schumann’s most beautiful melodies was intoned by Tom as he literally recreated the whole sonata before our incredulous eyes . There was a feeling that we were on a voyage of discovery together, with Tom at the helm taking us to places we never knew existed . And if he sometimes submerged the journey in a haze of mist, it was a mist of the golden beauty of Tom’s fantasy world .

It was to Liszt that the true soul of Tom found it ‘s goal. A monumental performance of a work rarely heard in the concert hall, I imagine because of its technical and musical complexity.

No encores were possible after such a monumental performance greeted by an ovation by an select public of musicians and connoisseurs of great piano playing

The encore we actually heard on Radio 3 this morning with a scintillating rondo by Weber from Tom’s ‘In Tune’ appearance last night.

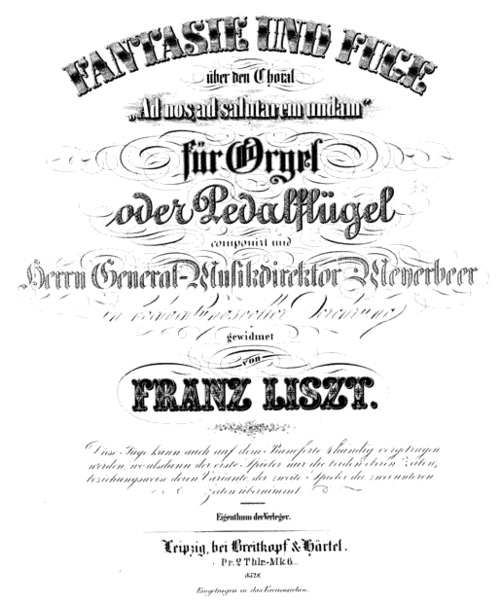

The Fantasy and Fugue on the chorale “Ad nos, ad salutarem undam”, S.259, is a piece of organ music composed by Franz Liszt in the winter of 1850 when he was in Weimar.The chorale on which the Fantasy and Fugue is based was from Act I of Giacomo Meyerbeer’s opera Le prophète. The work is dedicated to Meyerbeer, and it was given its premiere on October 29, 1852. The revised version was premiered in the Merseburg Cathedral on September 26, 1855, with Alexander Winterberger performing. The whole work was published by Breitkopf & Härtel in 1852, and the fugue was additionally published as the 4th piece of Liszt’s operatic fantasy “Illustrations du Prophète” (S.414). A piano duet version by Liszt appeared during the same time (S.624).The piece consists of three sections:

- Fantasy: opens with the “Ad nos” theme and then turns quiet and contemplative. The theme returns and eventually a climax is reached. A second climactic passage follows, after which this section ends.

- Adagio: serves as a development section, beginning quietly, the theme moving to major keys now from the minor keys of the preceding section. The piece brightens a bit in the latter half of this section.

- Fugue: serves as the finale, but also, within the sonata-form, as the recapitulation and coda. Elements from the previous sections appear again. The piece ends with a triumphant coda, on full organ.

A typical performance lasts nearly half an hour, although performances of the composition by Liszt and by Winterberger lasted, according to contemporary reports, an average of forty-five minutes.

Ferruccio Busoni prepared a piano arrangement which was published in 1897 by Breitkopf & Härtel. Alan Walker , Liszt’s biographer, said that it “represents one of the pinnacles of twentieth-century virtuosity.”Liszt at least once performed his own piano transcription, of which Walter Bache, his student, made an account in 1862. Liszt never seems to have notated such a version.