Interesting to hear the Fauré preludes played with such conviction and musicianly understanding. Able to unravel Fauré’s very individual voice and make sense with an architectural understanding and a sense of line of sumptuous beautiful sounds . It was the same intelligence and aristocratic nobility he brought to the Theme and variations. I remember Perlemuter telling me that Fauré, director of the Paris conservatoire where he was studying at the age 14 with Alfred Cortot, Fauré would send the music down for him to try out with the ink still wet on the page. With sentiment but never sentimental playing with clarity and simplicity. If Debargue allowed himself a little freedom or enjoyed his technical prowess it was because of youthful exuberance and did not interfere with the architectural shape or grandeur of Fauré’s unique musical voice.

There were disquieting signs, though, that showmanship could take the upper hand from his musicianship.This became more apparent and quite disconcerting in the Beethoven and Chopin that filled the first and second half of the programme. Some beautiful things in the first movement of Beethoven’s two movement op 90 sonata where the dynamic contrasts in the first movement and the sense of improvised finding his way overcame his rather harsh exaggerated exclamatory chords. But the second movement that Beethoven specifically asks to be played not too fast and in a singing style was played at breakneck speed with a coda that sounded more like a Moszkowski study ( who incidentally Perlemuter had also studied with ) and jumping up at the end in a crowd pleasing way was surprisingly disconcerting.

It was the same with Chopin’s Fourth scherzo with a middle section that he allowed to sing so naturally with sumptuous sound.The outer episodes , on the other hand, where Chopin’s wonderfully delicate embellishments flower so magically into wondrous bel canto were played like Liszt transcendental studies and loud chords were played with sledgehammer vehemence that had me jump in my seat.

It was the same in the second half where Beethoven’s ‘Moonlighting’ became so prolonged as Lucas chose to ignore Beethoven’s indication to play in two, and played in twelve – Moonlighting indeed ! The charm and simplicity of the minuet and trio were followed by a Presto agitato that the only thing we could hear were the two top sledgehammered chords at the end of a non existent run. I was surprised at the freedom he gave himself with the chordal passages and even more surprised by the misreading in the cadenza! The ending owed more to Tchaikovsky’s 1812 than to Beethoven’s Moonlighting!

Chopin’s 3rd Ballade was so grotesque and exaggerated with a crowd pleasing flourish at the end that it belied the remarkable scholarly musicianship of his Fauré.

Of course the audience rose to the bait and there were cries for more which Debargue very eloquently and charmingly offered with three encores.The first his own transcription of Fauré ‘Après un rève’ which owed more to piano bar than the refined finesse of one of Fauré ‘s most hauntingly touching songs .Another two paraphrases one of an early work again by Fauré and by great request a third encore, a paraphrase of Spanish idiom. Ravishing sounds and the jeux perlé we had been denied all evening were played with an improvised freedom and beauty that made one wonder why he had so distorted the works of others.

An ovation from the ‘Wiggies’ but I could not help feeling sad that a musician of his standing could become an entertainer, instead of the interpreter and master he obviously could be, as he demonstrated with his Fauré today and in his recent complete recordings .Fauré shunned virtuosity in favour of the classical lucidity often associated with the French. He was unimpressed by purely virtuoso pianists, saying, “the greater they are, the worse they play me.” Q.E.D Beware the temptation Monsieur Debargue!

“Since Glenn Gould’s visit to Moscow and Van Cliburn’s victory at the Tchaikovsky Competition in the heat of the Cold War, never has a foreign pianist provoked such frenzy.”

Olivier Bellamy, THE HUFFINGTON POST

incredible gift, artistic vision and creative freedom” of Lucas Debargue was revealed by his performances at the Tchaikovsky International Competition in Moscow in 2015 and distinguished with the coveted Prize of the Moscow Music Critics’ Association.

Today, Lucas is invited to play solo and with leading orchestras in the most prestigious venues of the world including Berlin Philharmonie, Concertgebouw Amsterdam, Konzerthaus Vienna, Théâtre des Champs Elysées and Philharmonie Paris, London’s Wigmore Hall and Royal Festival Hall, Alte Oper Frankfurt, Cologne Philharmonie, Suntory Hall Tokyo, the concert halls of Beijing, Shanghai, Taipei, Seoul, and of course the legendary Grand Hall of Tchaikovsky Conservatory in Moscow, the Mariinsky Concert Hall in St. Petersburg and Carnegie Hall in New York. He also appeared several times at the summer meetings of La Roque d’Anthéron and Verbier.

Lucas Debargue regularly collaborates with Valery Gergiev, Mikhail Pletnev, Vladimir Jurowski, Andrey Boreyko, Tugan Sokhiev, Vladimir Spivakov and Bertrand de Billy. His chamber music partners include Gidon Kremer, Janine Jansen, and Martin Fröst.

Born in 1990, Lucas forged a highly unconventional path to success. Having discovered classical music at the age of 10, the future musician began to feed his passion and curiosity with diverse artistic and intellectual experiences, which included advanced studies of literature and philosophy. The encounter with the celebrated piano teacher Rena Shereshevskaya proved a turning point: her vision and guidance inspired Lucas to make a life-long professional commitment to music.

A performer of fierce integrity and dazzling communicative power, Lucas Debargue draws inspiration for his playing from literature, painting, cinema, jazz, and develops very personal interpretation of a carefully selected repertoire. Though the core piano repertoire is central to his career, he is keen to present works by lesser-known composers like Karol Szymanowski, Nikolai Medtner, or Milosz Magin.

Lucas devotes a large portion of his time to composition and has already created over twenty works for piano solo and chamber ensembles. These include Orpheo di camera concertino for piano, drums and string orchestra, premiered by Kremerata Baltica, and a Piano Trio was created under the auspices of the Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris. As a permanent guest Artist of Kremerata Baltica, Lucas has been commissioned to write a chamber opera.

Sony Classical has released five of his albums with music of Scarlatti, Bach, Beethoven, Schubert, Chopin, Liszt, Ravel, Medtner and Szymanowski. His monumental four-volume tribute to Scarlatti, which came out at the end of 2019, has been praised by The New York Times and selected by NPR among “the ten classical albums to usher in the next decade”. August 2021 sees the release of an album devoted to the Polish composer Miłosz Magin. A true discovery of a fascinating yet unknown composer recorded with Kremerata Baltica and Gidon Kremer.

Lucas’s breakthrough at the Tchaikovsky Competition is the subject of the documentary To Music. Directed by Martin Mirabel and produced by Bel Air Media, it was shown at the International Film Festival in Biarritz in 2018.

Olivier Bellamy, Le HUFFINGTON POST

The pianist Alfred Cortot said, “There are few pages in all music comparable to these.” The critic Bryce Morrison has noted that pianists frequently prefer to play the charming earlier piano works, such as the Impromptu No. 2, rather than the later piano works, which express “such private passion and isolation, such alternating anger and resignation” that listeners are left uneasy.In his piano music, as in most of his works, Fauré shunned virtuosity in favour of the classical lucidity often associated with the French. He was unimpressed by purely virtuoso pianists, saying, “the greater they are, the worse they play me.” Fauré’s stature as a composer is undiminished by the passage of time. He developed a musical idiom all his own; by subtle application of old modes, he evoked the aura of eternally fresh art; by using unresolved mild discords and special coloristic effects, he anticipated procedures of Impressionism; in his piano works, he shunned virtuosity in favor of the Classical lucidity of the French masters of the clavecin ; the precisely articulated melodic line of his songs is in the finest tradition of French vocal music. .Fauré’s stylistic evolution can be observed in his works for piano. The elegant and captivating first pieces, which made the composer famous, show the influence of Chopin, Saint-Saëns, and Liszt. The lyricism and complexity of his style in the 1890s are evident in the Nocturnes nos. 6 and 7, the Barcarolle no. 5 and the Thème et variations. Finally, the stripped-down style of the final period informs the last nocturnes (nos.10–13), the series of great barcarolles (nos. 8–11) and the astonishing Impromptu no. 5.

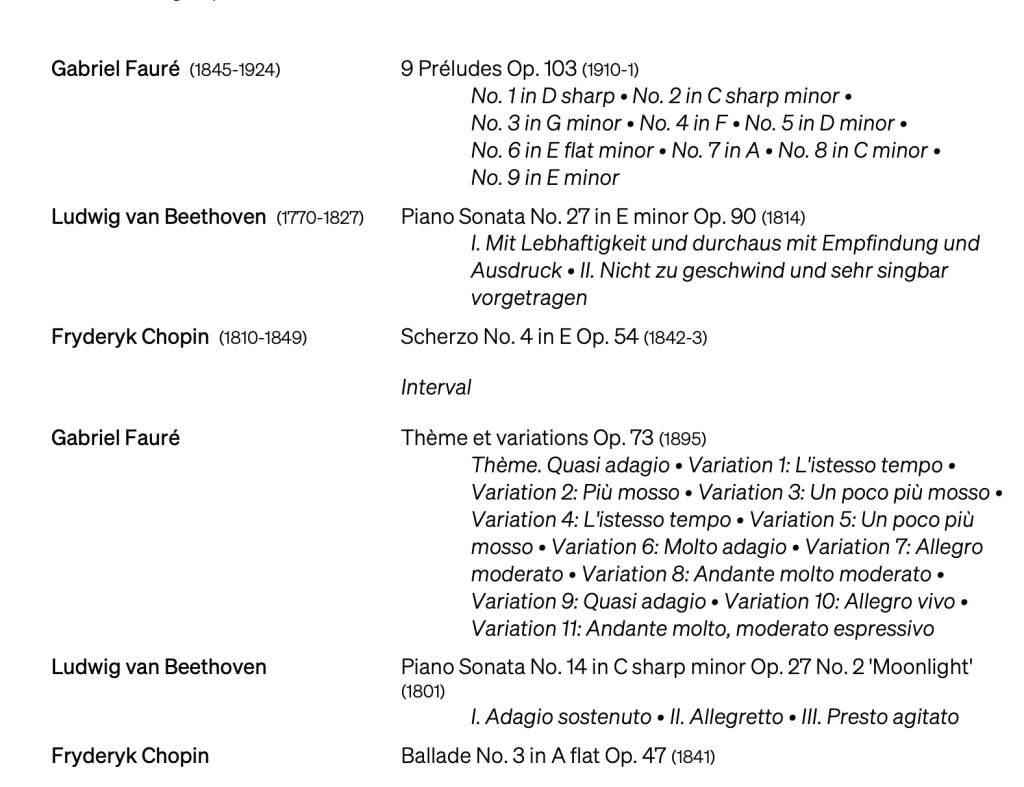

9 Préludes, Op. 103

The nine préludes are among the least-known of Fauré’s major piano compositions. They were written while the composer was struggling to come to terms with the onset of deafness in his mid-sixties. By Fauré’s standards this was a time of unusually prolific output. The préludes were composed in 1909 and 1910, in the middle of the period in which he wrote the opera Pénélope, barcarolles Nos. 8–11 and nocturnes Nos. 9–11.

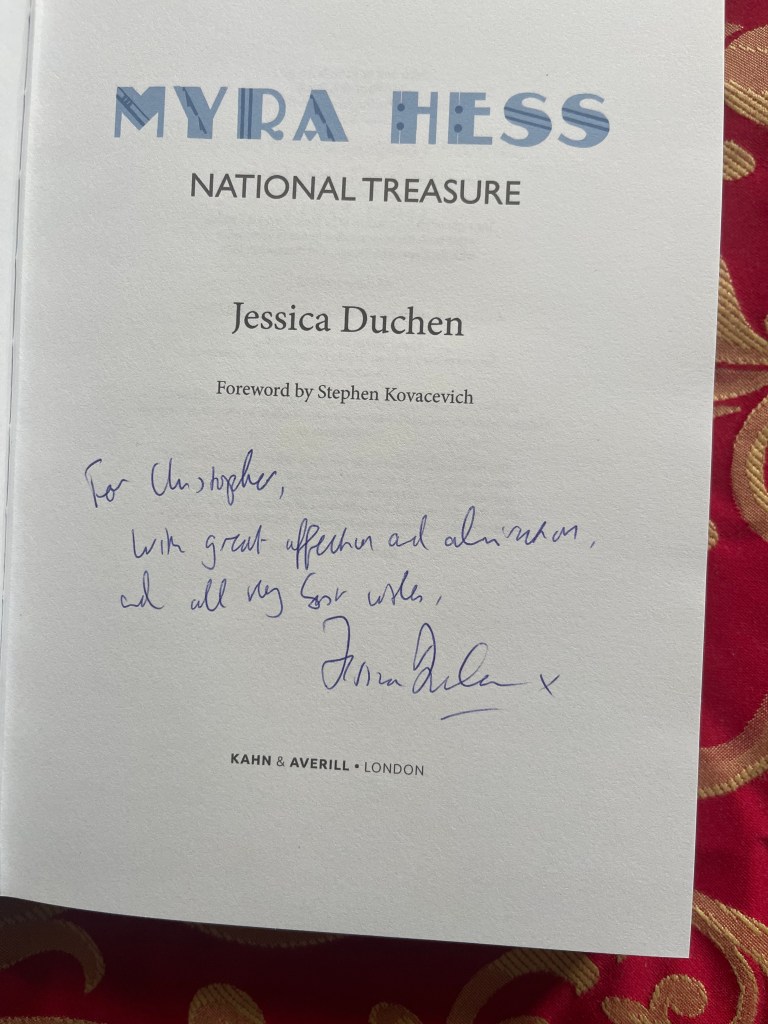

In Koechlin’s view, “Apart from the Préludes of Chopin, it is hard to think of a collection of similar pieces that are so important”. The critic Michael Oliver wrote, “Fauré’s Préludes are among the subtlest and most elusive piano pieces in existence; they express deep but mingled emotions, sometimes with intense directness … more often with the utmost economy and restraint and with mysteriously complex simplicity.” Jessica Duchen calls them “unusual slivers of magical inventiveness.” The complete set takes between 20 and 25 minutes to play. The shortest of the set, No. 8, lasts barely more than a minute; the longest, No. 3, takes between four and five minutes.

Prélude No. 1 in D♭ major

Andante molto moderato. The first prélude is in the manner of a nocturne.Morrison refers to the cool serenity with which it opens, contrasted with the “slow and painful climbing” of the middle section.

Prélude No. 2 in C♯ minor

Allegro. The moto perpetuo of the second prélude is technically difficult for the pianist; even the most celebrated Fauré interpreter can be stretched by it. Koechlin calls it “a feverish whirling of dervishes, concluding in a sort of ecstasy, with the evocation of some fairy palace.Prélude No. 3 in G minor

Andante. Copland considered this prélude the most immediately accessible of the set. “At first, what will most attract you, will be the third in G-minor, a strange mixture of the romantic and classic ,it might be a barcarolle strangely interrupting a theme of very modern stylistic contour”.

Prélude No. 4 in F major

Allegretto moderato. The fourth prélude is among the gentlest of the set. The critic Alain Cochard writes that it “casts a spell on the ear through the subtlety of a harmony tinged with the modal and its melodic freshness.” Koechlin calls it “a guileless pastorale, flexible, with succinct and refined modulations”.

Prélude No. 5 in D minor

Allegro. Cochard quotes the earlier writer Louis Aquettant’s description of this prélude as “This fine outburst of anger (Ce bel accès de colère)”. The mood is turbulent and anxious; the piece ends in quiet resignation reminiscent of the “Libera me” of the Requiem.

Prélude No. 6 in E♭ minor

Andante. Fauré is at his most classical in this prélude, which is in the form of a canon . Copland wrote that it “can be placed side by side with the most wonderful of the Preludes of the Well-Tempered Clavichord.”Prélude No. 7 in A major

Andante moderato. Morrison writes that this prélude, with its “stammering and halting progress” conveys an inconsolable grief. After the opening andante moderato, it becomes gradually more assertive, and subsides to conclude in the subdued mood of the opening.The rhythm of one of Fauré’s best-known songs, “N’est-ce-pas?” from La bonne chanson , runs through the piece.

Prélude No. 8 in C minor

Allegro. In Copland’s view this is, with the third, the most approachable of the Préludes, “with its dry, acrid brilliance (so rarely found in Faure).”Morrison describes it as “a repeated-note scherzo” going “from nowhere to nowhere.”

Prélude No. 9 in E minor

Adagio. Copland described this prélude as “so simple – so absolutely simple that we can never hope to understand how it can contain such great emotional power.” The prélude is withdrawn in mood; Jankélévitch wrote that it “belongs from beginning to end to another world.” Koechlin notes echoes of the “Offertoire” of the Requiem throughout the piece.

Thème et variations in C♯ minor, Op. 73

Written in 1895, when he was 50, this is among Fauré’s most extended compositions for piano Copland wrote of the work:

‘Certainly it is one of Faure’s most approachable works. Even at first hearing it leaves an indelible impression. The “Theme” itself has the same fateful, march-like tread, the same atmosphere of tragedy and heroism, that we find in the introduction of Brahms’s First Symphony. And the variety and spontaneity of the eleven variations which follow bring to mind nothing less than the Symphonic Studies . How many pianists, I wonder, have not regretted that the composer disdained the easy triumph of closing on the brilliant, dashing tenth variation. No, poor souls, they must turn the page and play that last, enigmatic (and most beautiful) one, which seems to leave the audience with so little desire to applaud.’

POINT AND COUNTERPPOINT

Pianist Lucas Debargue is the real deal – Jessica Duchen writes :

Pianist Lucas Debargue is the real deal