https://youtube.com/watch?v=yPAHDiWFZw4&feature=shared

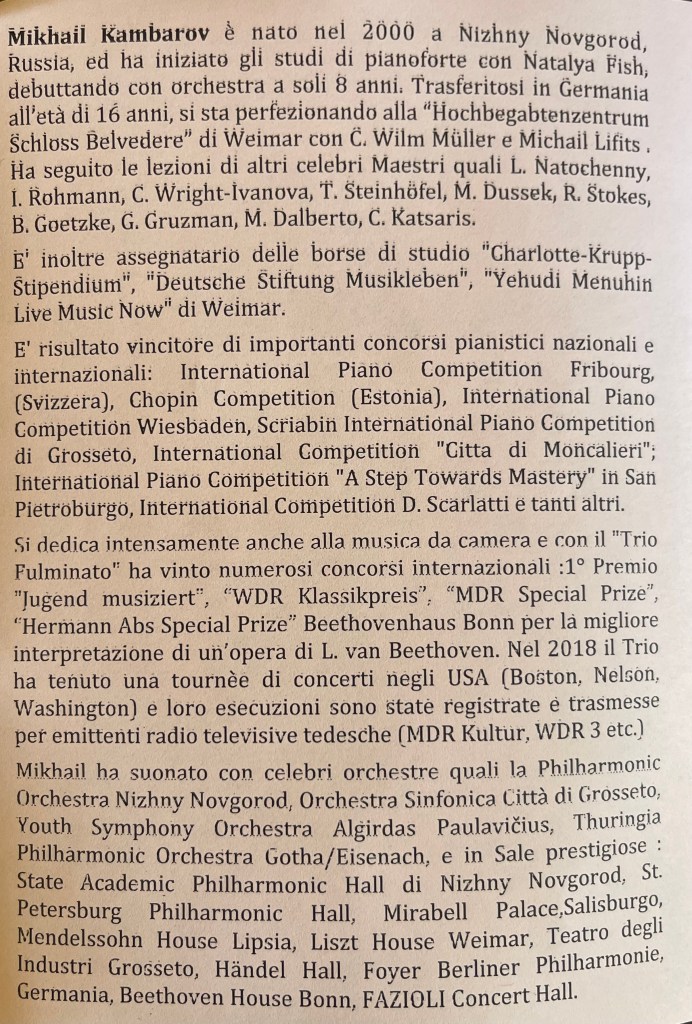

Playing of beauty and intelligence from Mikhail Kambarov in Ischia at the Walton Estate of La Mortella. A sense of style like pianists from another age, when the piano became a multicoloured box of jewels in the hands of musicians that were above all magicians.

There are very few of the younger generation who are prepared to climb onto the high wire and risk falling off or even worse falling into habits of crowd pleasing juggling of notes.

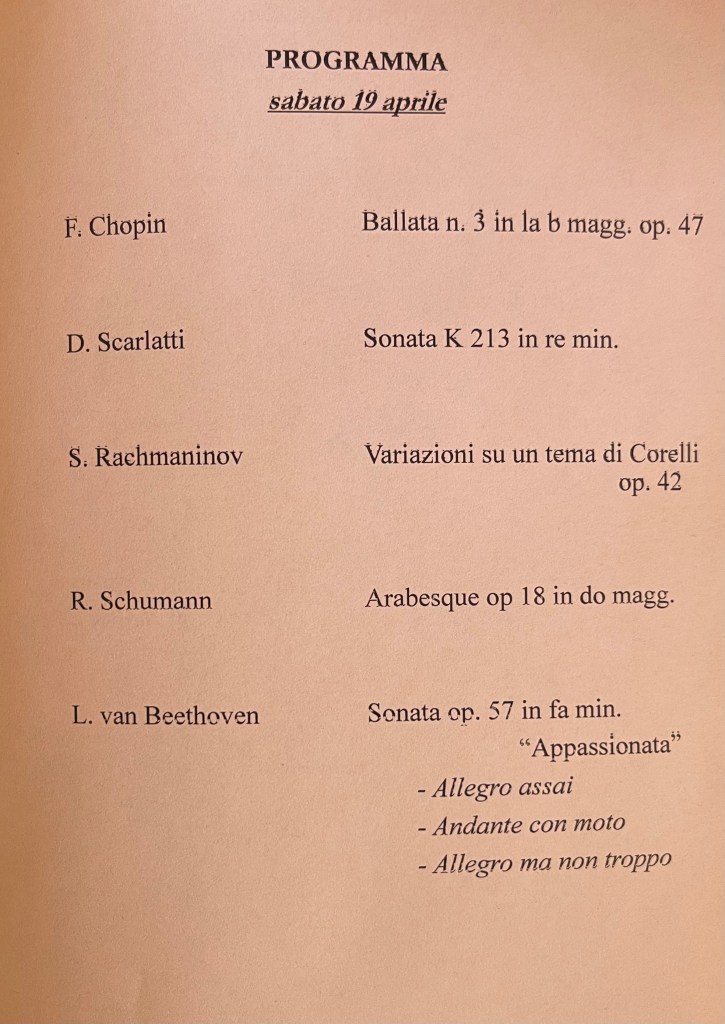

It was evident from the very first notes of Chopin 3rd Ballade that here was a pianist who had something to say. With respect and humility for the composer he added his own sense of imagination and a wondrous palette of colour that brought a radiance and subtle beauty to all he played. There was a disarming simplicity to his Chopin that from the pastoral opening, plaintiff whispered gasps gently entered the scene as almost imperceptibly they were allowed to grow on an ever more passionate wave of sounds. Momentarily interrupted by scenes of ravishing fioritura or dynamic pulsating energy but nothing could interrupt this continual flow of beauty riding on a wave of radiance and at times even menace. Bursting into a glorious outpouring of joyous exhilaration before plunging from on high to the final chords that were played quite sedately. They were after all merely the conclusion of a miniature tone poem with an architectural shape of poetic musicianship.

There was exquisite fluidity and disarming poignancy to the whispered intimate secrets that he shared with us in Scarlatti’s D minor sonata. Magic, as we had to strain to listen to the central episode such was this young man’s ability to draw us in to his world of intimate secrets rather than projecting out with more usual stylistic correctness. We were astonished by the genial poetic invention of Scarlatti who not only created over 500 sonatas of the brilliant jeux perlé perfection of his age, but also added many, demonstrating that Scarlatti had a heart and soul that dared speak to all those with the same poetic sensibility with which they were born. Mikhail’s discerning intelligent musicianship, too,was clear from a programme where the D minor of Scarlatti was but a preparation for the world of ‘La Folia’ ( also in D minor), in the hands of a composer born into a world two centuries on.

Rachmaninov’s ‘Corelli’ variations are dedicated to Fritz Kreisler and it was in fact Kreisler that mislead his doting public with compositions that he claimed were found in the archives of baroque music but admitted later that they had been penned by him in the style of ……!

‘La Folia’ too was not actually composed by Corelli but a popular melody that was used by many composers as a basis for variations, Liszt being the prime example with his Spanish Rhapsody.

However a Rose is always a Rose, whoever its creator really was (or as Kreisler said ‘ the name changes but the value remains!’ ), and it was Mikhail’s genial idea to combine Scarlatti with ‘La Folia’, alas foiled by a public enthused by his sublime playing of Scarlatti and wanting to show their appreciation!

Later in the second half, where Mikhail again wanted to preface Beethoven’s ‘Appassionata’ with Schumann’s ‘Arabesque’, this time he was ready and waiting to pounce before the public could!

Mikhail brought purity and beauty to the theme of ‘La Folia’ ready for the variations to evolve as an almost continuous outpouring of emotions inspired by this ravishing melody. The first variation opened with beguiling subtlety, with pointed comments added of syncopated dryness.The second took wing with a perpetuum mobile of insinuating propulsion, leading to the presumptuous question and beseeching answer of the third. The variations were revealed with a fantasy of sumptuous sounds and a dynamic drive of subtle mastery. There was a poignant cry of liquid sounds of extraordinary potency as the midway cadenza took wing descending with poetic improvised freedom and revealing ‘La Folia’ in all its naked major costume. Dynamic drive and technical mastery in the last three variations found rest on the pedal note of ‘D’ on which a wondrous melody was floated of bewitching, unmistakably Rachmaninovian harmonies of brooding nostalgia, before ‘La Folia’ returned ,in whispered tones, to complete this remarkably concise and poetic work.

It is only now that many of the lesser known works of Rachmaninov are being heard in the concert hall, and a composer known mostly for his Hollywood style romanticism encased in a blinding amount of knotty twine is now being appreciated as a master of his craft with variations not only on a theme of Paganini but also on Chopin’s equally disarmingly simple Prelude in C minor.

Mikhail gave a remarkable performance that was justly received with an ovation and a well earned pause before the equally taxing second half of the programme.

Schumann’s ‘Arabesque’ was played with a wondrous flexibility, allowing the music to unfold and speak so naturally. There were beautiful inner doublings that just underlined the melodic line with the refined good taste of a poet giving more richness to the sound , as the passion rose for an outpouring of noble beauty. An architectural shape to a work that in lesser hands can seem sweetly repetitive, but in a true poet’s hands returns to the original inspiration, as when the music was still wet on the page. Yearning, passionate with disarming simplicity as Mikhail brought his fantasy and colour to bear, turning a bauble into a gem,( as indeed Horowitz was to do with it’s twin: ‘Blumenstück’ op 19 which immediately followed this ‘Arabesque’ op 18). A coda of the same magic as ‘Dichterliebe’ (op. 48, the song cycle by Schumann), music reaching places where words are just not enough. A glowing radiance and beauty to the final page with a fluidity and the glowing sounds of purity with the deep significance of a poet of the piano. https://youtu.be/Ka5x167wNt8

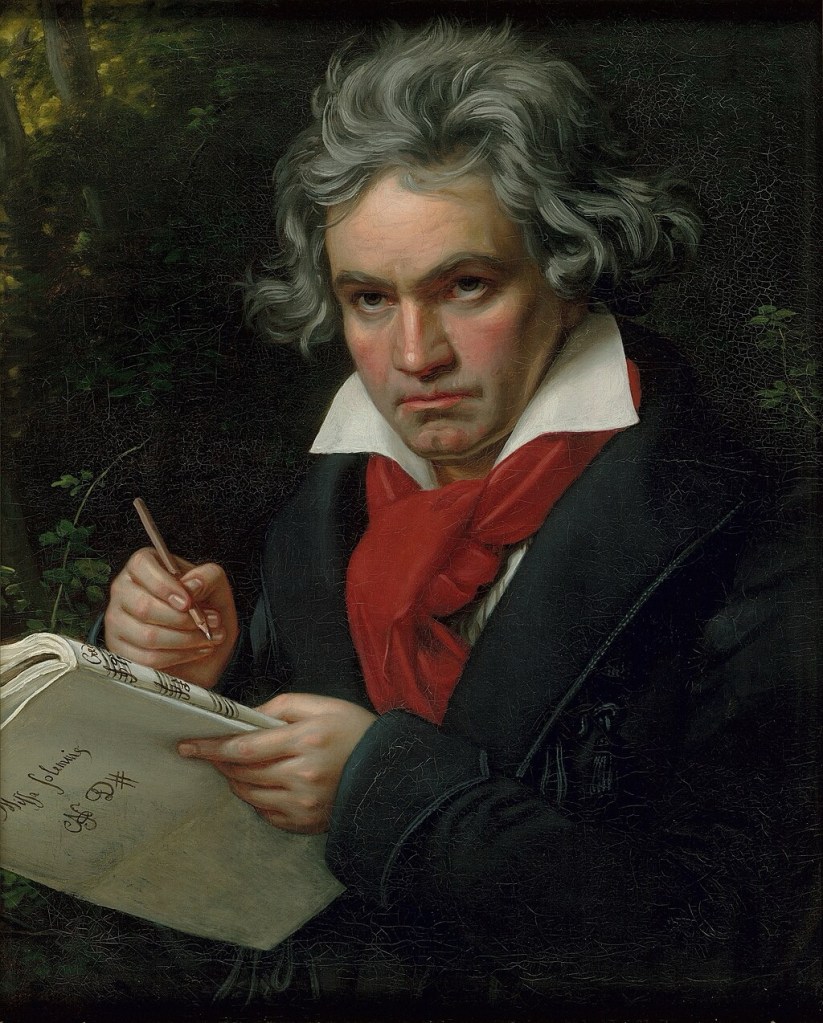

Leaving his hand on the final note, which he miraculously transformed into the whispered opening of Beethoven’s ‘Appassionata’. There was an extraordinary dynamic range and sense of drama that kept us on the edge of our seats. A scrupulous attention to Beethoven’s very precise indications meant that seemingly impossible explosions of notes were played with the struggle that Beethoven implied, not simplifying the execution by sharing between the hands. This is not play safe music but only for the fearless that dare open the door to a revolutionary work of its day. Performances that even today should still have that same astonishing struggle that Beethoven was to bequeath to the world. The music like a tightly spun spring unfolding with breathtaking drive and intensity. Even the return of the theme was over a bubbling cauldron of sounds boiling over at 100 degrees. Beethoven’s revolutionary and poetic effects were interpreted with remarkable authentic intuition and the final pedal effect of the coda came after an astonishingly violent chord out of which a whole world was allowed to dissolve and disappear into the distance, where we were to envisage a funeral procession of sumptuous beauty. An ‘Andante con moto’ played with sumptuous rich sounds of string quartet quality, where every strand has a meaning and poignant significance. The variations unfolded with beauty, the deep legato bass of the first with chords interjecting unusually promptly above, which contrasted with the golden beauty of the second mellifluous variation. Gradually building in agitation until the astonishing unsettling chords of the diminished 7th, firstly barely suggested and then thrown at us with Beethovenian vehemence. The continual drive of the ‘Allegro ma non troppo’ , Mikhail played with relentless forward movement of turbulent control. Exhilaration and excitement of the coda brought this recital to a astonishing end and an ovation from a Saturday afternoon audience who had come to admire the beauty of Susana’s Ischian Paradise and were not expecting to be astonished by the presumption of Beethoven.

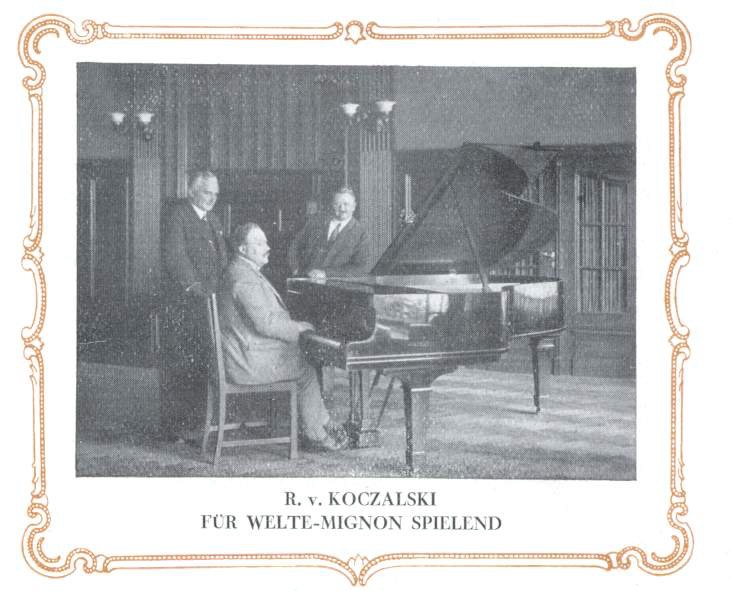

It was now that Mikhail could let his hair down and show us his admiration for the sound world of pianists ‘old style’ from the Golden age. Artists like De Pachmann, Rosenthal, Lhevine or Friedman, when a black box of hammers and strings could be turned into a box of gleaming jewels.

A truly fascinating historical piano recording is this June 28, 1938 recording of Chopin’s famous Nocturne in E-Flat Major Op.9 No.2 ‘with authentic variants’ played by Raoul Koczalski, who studied with Chopin’s pupil Karol Mikuli.

https://youtu.be/cW-VRsOeIwM?si=PpdgETkXYHqfHULa

As a young child, Koczalski famously had lessons with Chopin’s pupil Karol Mikuli over the course of four consecutive summers from 1892 to 1895, but he had trained with a number of teachers: Julian Gadomski, Ludwig Marek, and Henryk Jarecki. Some have sought to minimize the extent to which he studied with Mikuli but Koczalski detailed the extent of their work together, noting that “it was no mere trifle: each lesson lasted two full hours and these were daily lessons. I was never permitted to work alone…Nothing was neglected: posture at the piano, fingertips, use of the pedal, legato playing, staccato, portato, octave passages, fiorituras, phrase structure, the singing tone of a musical line, dynamic contrasts, rhythm, and above all the care for authenticity with which Chopin’s works must be approached. Here there is no camouflage, no cheap rubato, and no languishing or useless contortions.”

Chopin’s Nocturne in E flat op 9 n. 2 was played by Mikhail with whispered beauty and barely suggested asides with embellishments that were in fact described in the most recent authentic edition of Chopin.

The Jan Ekier edition takes into account the pages of manuscripts that Chopin would give to his noble women students in Paris and also letters of the time describing Chopin’s own performances. The edition was completed in 2010, in time for the bicentenary of Chopin’s birth and as an urtext, the Chopin National Edition aims to produce a musical text that adheres to the original notation and the composer’s intentions. All extant sources were analyzed and verified for authenticity, mainly autographs, first editions with Chopin’s corrections and pupils’ copies with Chopin’s annotations. Necessary editorial decisions are documented in each volume’s source commentary. Additionally, a separate performance commentary documents cases where Chopin’s notation may be misunderstood by contemporary pianists, such as realizations of ornaments and pedaling. In Ekier’s own words : ‘We owe Chopin a debt… His music allowed us to survive the worst moments, and in the periods of hope extols Polish culture all over the world. We owe it to the author to publish his work in the form he intended. This is the goal of the National Edition: to pay off a Nation’s debt to Chopin.’

was a Polish pianist and composer

The Chopin National Edition consists of 36 volumes in two series, for works published during Chopin’s lifetime (Series A), and for works published posthumously (Series B). A 37th volume (titled Supplement) consists of compositions partly by Chopin, for instance his contribution to Hexameron.

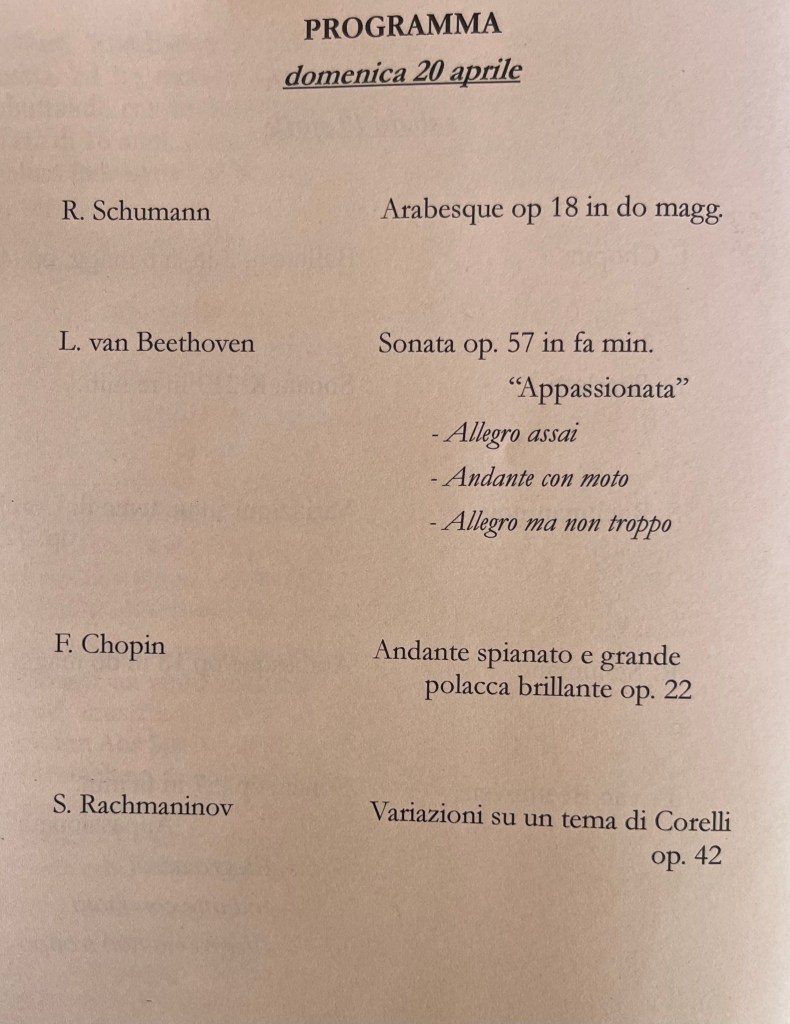

The second concert in Ischia there was another work by Chopin: the ‘Andante Spianato and Grande Polonaise’ op 22 in place of the ‘Third Ballade’. And what a performance this was ,truly worthy of the great pianists of the past, with a ‘jeux perlé’ at the end of the Polonaise that I have never heard played with such refined elegance and supreme golden sounds of ravishing beauty. An ‘Andante Spianato’ of exquisite beauty and subtle phrasing, always supported by sumptuous bass harmonies of luxuriant velvet clad intoxicating beauty. Interrupted by the orchestral introduction to the Polonaise where the pizzicato notes I have never heard played with such a delicate diminuendo as they lead the way to the Polonaise, that was played with suave elegance. A ‘joie de vivre’ of refined playfulness with an extraordinary sense of measure and balance. Even the octave declarations were played with a mellifluous beauty and not the more usual hard hitting showmanship.There was also a subtle beauty as light was shed on certain inner notes, like a will o’ the wisp lighting up the night sky with their magic wand. A quite extraordinary performance where I am not sure if it was he or us that was having such self indulgent enjoyment .

Chopin’s own performances sprang to mind as it must have been like this that the young Chopin took the Parisian Salons by storm, with poetic genius and refined brilliance.

‘Hats off, a Genius’ , declared Schumann and tonight we could understand why !

A standing ovation and two encores ( the Scarlatti Sonata from yesterday and the Chopin Nocturne op 9 n. 2 ) in an afternoon of absolute magic that rarely has been experienced in this Paradise .

28 March 1943 (aged 69) Beverly Hills , California, U.S.

Variations on a Theme of Corelli op. 42, is a set of variations for solo piano, written in 1931 by the Russian composer Sergei Rachmaninov . He composed the variations at his holiday home in Switzerland.

The theme is La Folia, which was not in fact composed by Arcangelo Corelli , but was used by him in 1700 as the basis for 23 variations in his Sonata for violin and continuo (violone and/or harpsichord) in D minor, Op. 5, No. 12. La Folia was popular as a basis for variations in Baroque music. Franz Liszt used the same theme in his Rhapsodie espagnole S. 254 (1863).Rachmaninoff dedicated the work to his friend the violinist Fritz Kreisler with whom he often played in recitals together. He wrote to another friend, the composer Nikolai Medtner, on 21 December 1931:

I’ve played the Variations about fifteen times, but of these fifteen performances only one was good. The others were sloppy. I can’t play my own compositions! And it’s so boring! Not once have I played these all in continuity. I was guided by the coughing of the audience. Whenever the coughing would increase, I would skip the next variation. Whenever there was no coughing, I would play them in proper order. In one concert, I don’t remember where – some small town – the coughing was so violent that I played only ten variations (out of 20). My best record was set in New York, where I played 18 variations. However, I hope that you will play all of them, and won’t “cough”.

Rachmaninoff recorded many of his own works, but this piece wasn’t one of them.

The Theme is followed by 20 variations, an Intermezzo between variations 13 and 14, and a Coda to finish. All variations are in D minor except where noted.

- Theme. Andante

- Variation 1. Poco piu mosso

- Variation 2. L’istesso tempo

- Variation 3. Tempo di Minuetto

- Variation 4. Andante

- Variation 5. Allegro (ma non tanto)

- Variation 6. L’istesso tempo

- Variation 7. Vivace

- Variation 8. Adagio misterioso

- Variation 9. Un poco piu mosso

- Variation 10. Allegro scherzando

- Variation 11. Allegro vivace

- Variation 12. L’istesso tempo

- Variation 13. Agitato

- Intermezzo

- Variation 14. Andante (come prima) (D♭ major)

- Variation 15. L’istesso tempo (D♭ major)

- Variation 16. Allegro vivace

- Variation 17. Meno mosso

- Variation 18. Allegro con brio

- Variation 19. Piu mosso. Agitato

- Variation 20. Piu mosso

- Coda. Andante

One of his greatest and most technically challenging sonatas , the Appassionata was considered by Beethoven to be his most tempestuous piano sonata until the Hammerklavier1803 was the year Beethoven came to grips with the irreversibility of his progressive hearing loss. It was composed during 1804 and 1805, and perhaps 1806, and Beethoven dedicated it to cellist and his friend, Count Franz Brunswick. The first edition was published in February 1807 in Vienna.

Unlike the early Pathétique , the Appassionata was not named during the composer’s lifetime, but was so labelled in 1838 by the publisher of a four-hand arrangement of the work. Instead, Beethoven’s autograph manuscript of the sonata has “La Pasionata” written on the cover, in Beethoven’s hand.The sonata consists of three movements:

Allegro assai Andante con moto. Allegro ma non troppo – Presto

Beethoven started writing the Sonata n. 23 in the summer of 1804. After the first two movements were outlined, the composer had difficulty finding the right idea for the final movement. Ferdinand Ries (1784–1838) described the moment of inspiration. The two of them had been walking in the woods when the inspiration hit: We went so far lost that we didn’t get back… to where Beethoven lived, until almost eight o’clock. All the way he hummed, or even howled to himself, up and down, up and down. down without singing any definite notes. When I asked him what this was, he replied: I have thought of a theme for the last movement of the sonata. When we entered the room, he ran to the piano without removing his hat. I took a seat in the corner and he soon forgot about me. He burst in for at least an hour with the new ending to the sonata, which is so beautiful. He finally got up, was surprised to see that I was still there, and told me: I can’t teach you a lesson today. I still have work to do.

During this time, Josephine Deym (née Brunsvik, 1779–1821) resumed lessons with Beethoven after her husband’s death. As the months passed, Beethoven’s earlier attraction to her was rekindled. He wrote the song An die Hoffnung, Op. 32, for her, as well as thirteen cards that became more and more loving. There is evidence that the composer proposed to him. It is believed that she returned his love, but she could not marry below her position for the protection of her four children, for if she did, she would lose both her noble title and her security. After rejecting the composer, she remarried in 1810, forging an unsuccessful union with Baron Christoph Von Stackelberg (1777-1841). The couple separated in 1813. It was once thought that Josephine might be the subject of Beethoven’s famous love letter to the Immortal Beloved, but recent evidence has refuted that possibility.

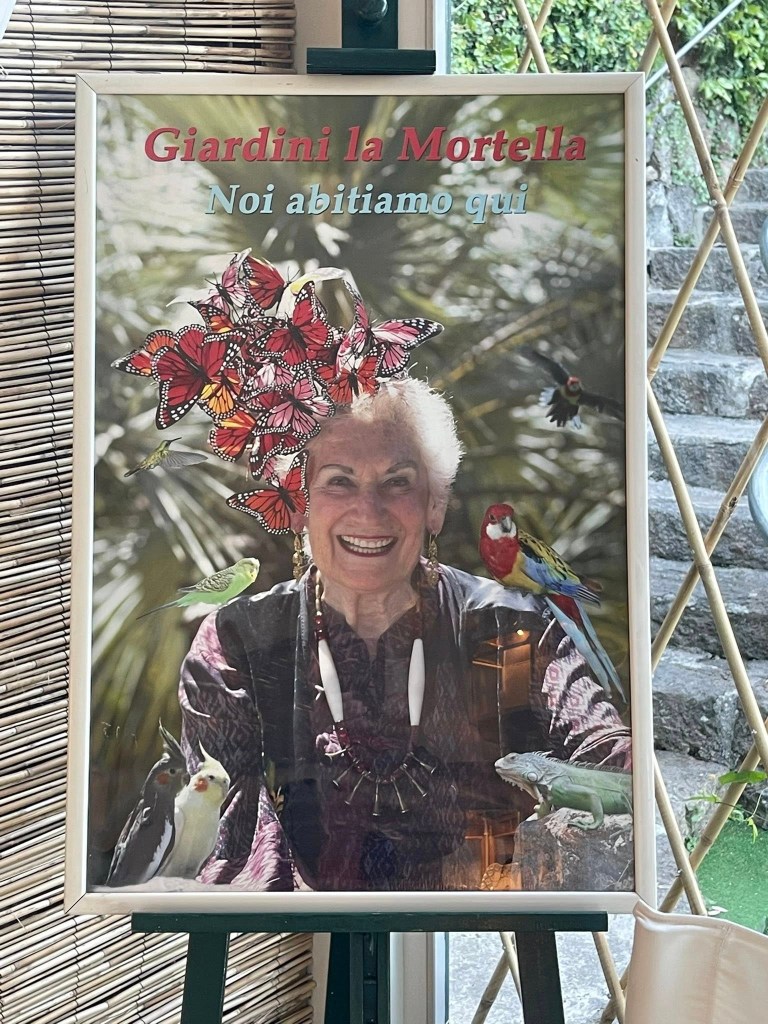

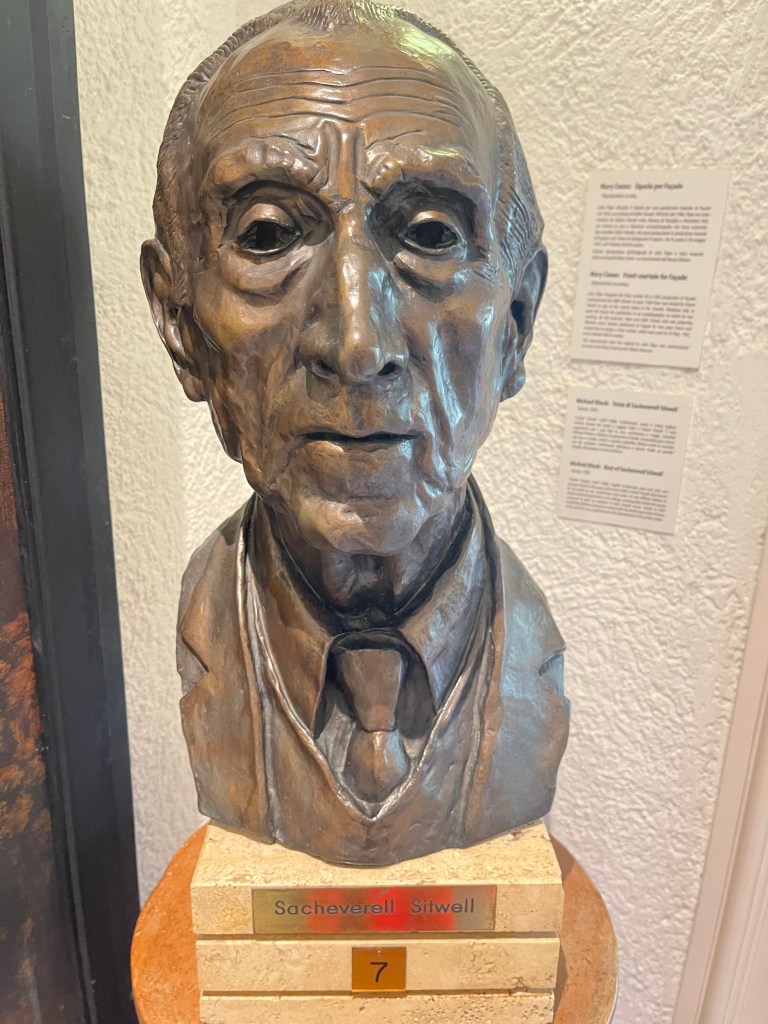

This is my 8th visit to the Walton Foundation bringing wonderful young musicians to breathe the rarified air that was the intent of William and Susana Walton.Their wishes are being respected with dedication and warmth, the founders looking on from their perch where they can view the world inside and out of La Mortella .

Thomas Kelly on Ischia – The Walton Foundation at La Mortella -‘The Devil and the Deep blue Sea’

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2023/10/15/thomas-kelly-on-ischia-the-walton-foundation-at-la-mortella-the-devil-and-the-deep-blue-sea/

Pedro Lopez Salas in Paradise .A standing ovation at La Mortella – The Walton Foundation

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2023/09/05/pedro-lopez-salas-in-paradise-a-standing-ovation-at-la-mortella-the-walton-foundation/

Andrzej Wiercinski at La Mortella Ischia The William Walton Foundation – Refined artistry and musical intelligence in Paradise

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2023/05/11/andrzej-wiercinski-at-la-mortella-ischia-the-william-walton-foundation-refined-artistry-and-musical-intelligence-in-paradise/

Kyle Hutchings A poetic troubadour of the piano reveals the heart of Mozart,Schubert and Franck the Keyboard Trust Concert Tour of Adbaston ,Ischia,Florence and Milan

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2024/09/11/kyle-hutchings-a-poetic-troubadour-of-the-piano-reveals-the-heart-of-mozartschubert-and-franck-the-keyboard-trust-concert-tour-of-adbaston-ischiaflorence-and-milan/

Misha Kaploukhii mastery and clarity in Walton’s paradise where dreams become reality – updated to include the Sheepdrove Competition and graduation recital

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2024/05/05/misha-kaploukhii-mastery-and-clarity-in-waltons-paradise-where-dreams-become-reality/

Magdalene Ho A musical genius in Paradise

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2024/05/12/magdalene-ho-a-musical-genius-in-paradise/

Yuanfan Yang in paradise

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2021/09/06/yuanfan-yang-in-paradise/

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2024/03/20/christopher-axworthy-dip-ram-aram/