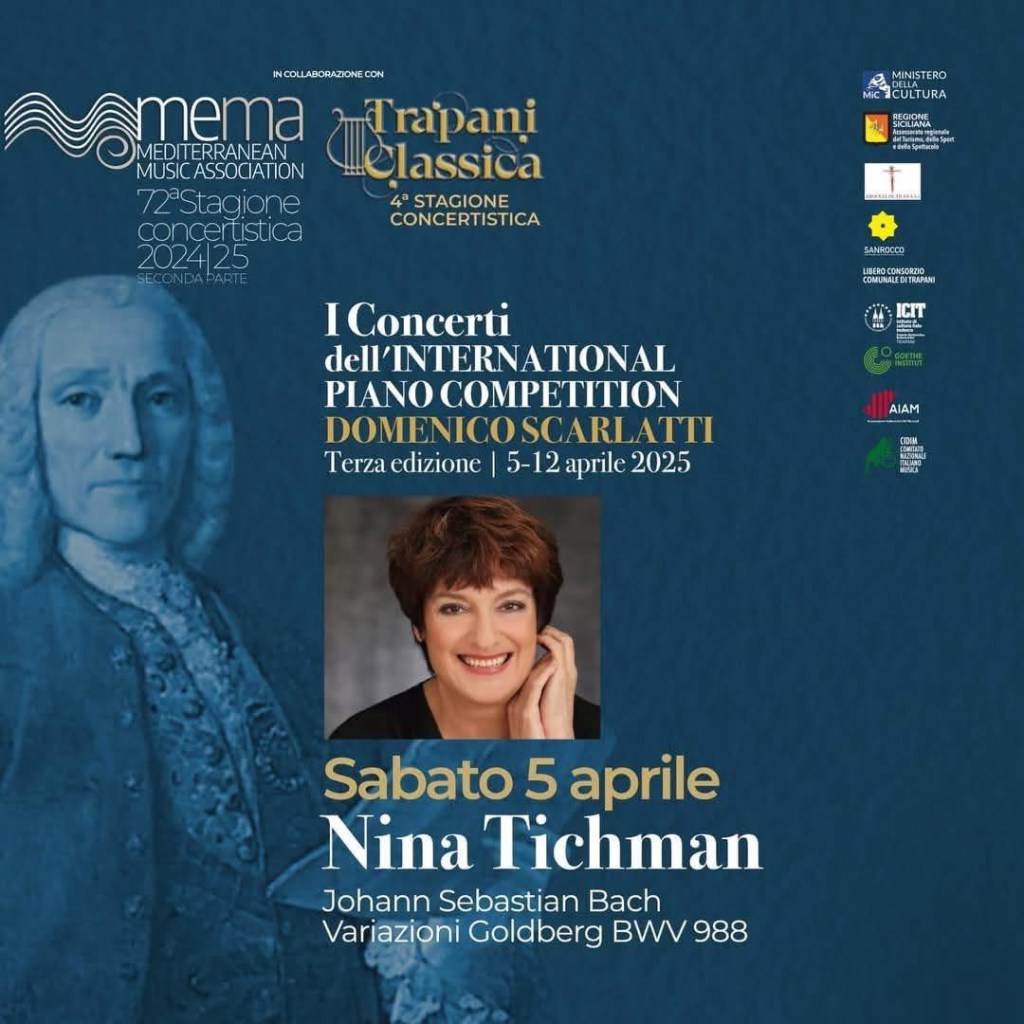

I was sorry to miss Nina Tichman’s concert in Trapani ,the wonders of which were still echoing around Trapani on my arrival for the 3rd International Piano Competition Domenico Scarlatti .

Luckily Vincenzo Marrone had thought to share such wonders, after the competition final, with the magnificent Politeama Garibaldi in nearby Palermo, thanks to Donatella Sollima, the artistic director of Palermo’s Associazione Siciliana Amici della musica and a fellow jury member of his competition .

A hall, she tells me, that her father used to bring her as a little girl to listen to artists ,who have now passed into legend, such as Rubinstein ,Kempff,Cherkassky and all the greatest musicians of the age .

A miniature Royal Albert Hall, in which one can feel the presence of it’s past glorious history.

Not only past because Donatella has continued the great tradition and this season the hall has resounded to the magic of Arcadi Volodos, Misha Maisky, Martha Argerich and now to close the season Nina Tichman .

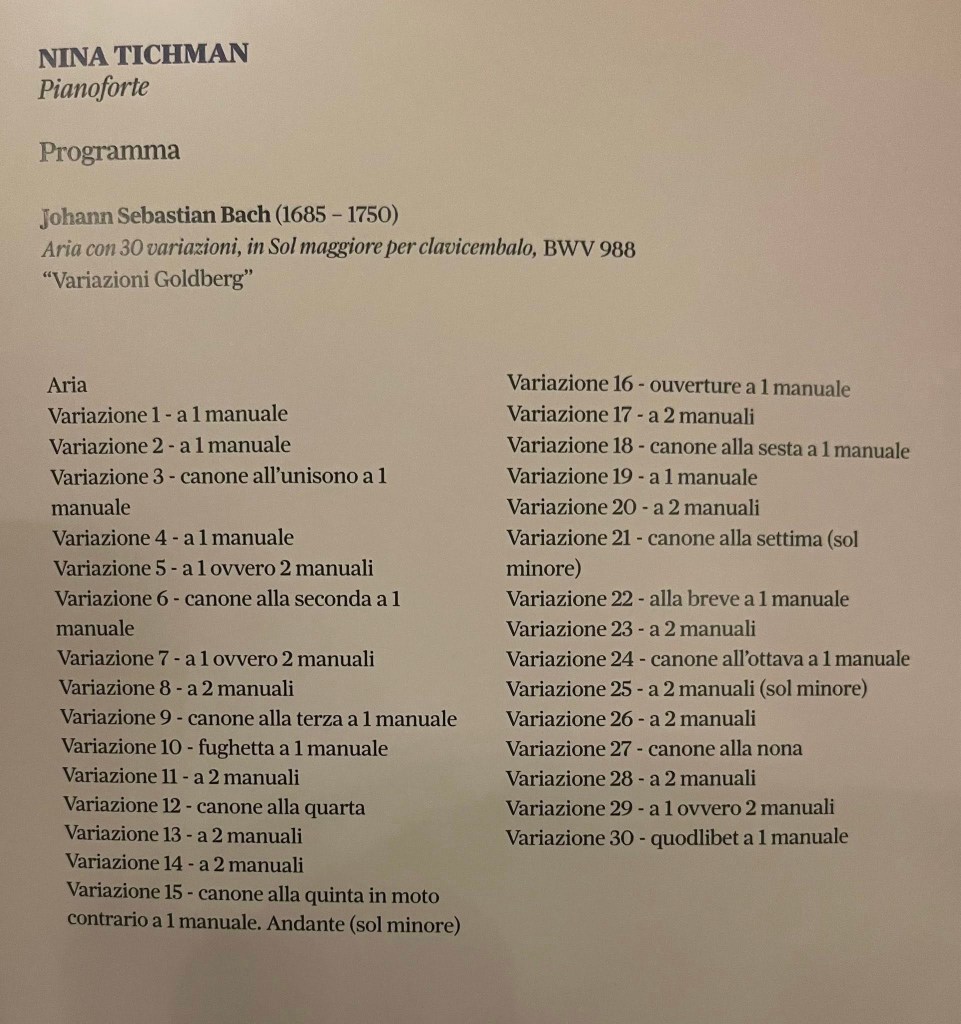

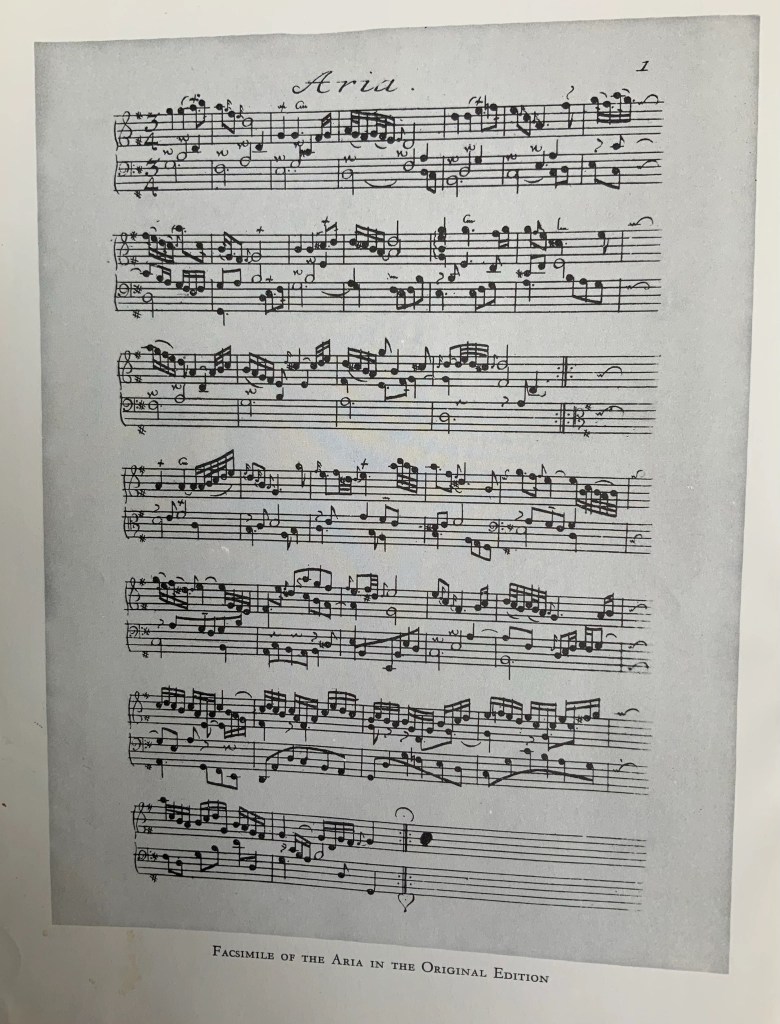

What greater gift could there be for a city steeped in history than a performance of the greatest variations ever written for the keyboard : Bach’s mighty ‘Goldberg Variations’.

Eighty five minutes of sublime music, all created on the simplest of ground basses that Nina as an ‘encore’ revealed in all its naked simplicity. This was after listening with baited breath to the beauty of her performance, played without the score ,and with the subtle pianistic perfection of one of the greatest exponents of the almost forgotten Matthay School of extreme sensibility of touch.

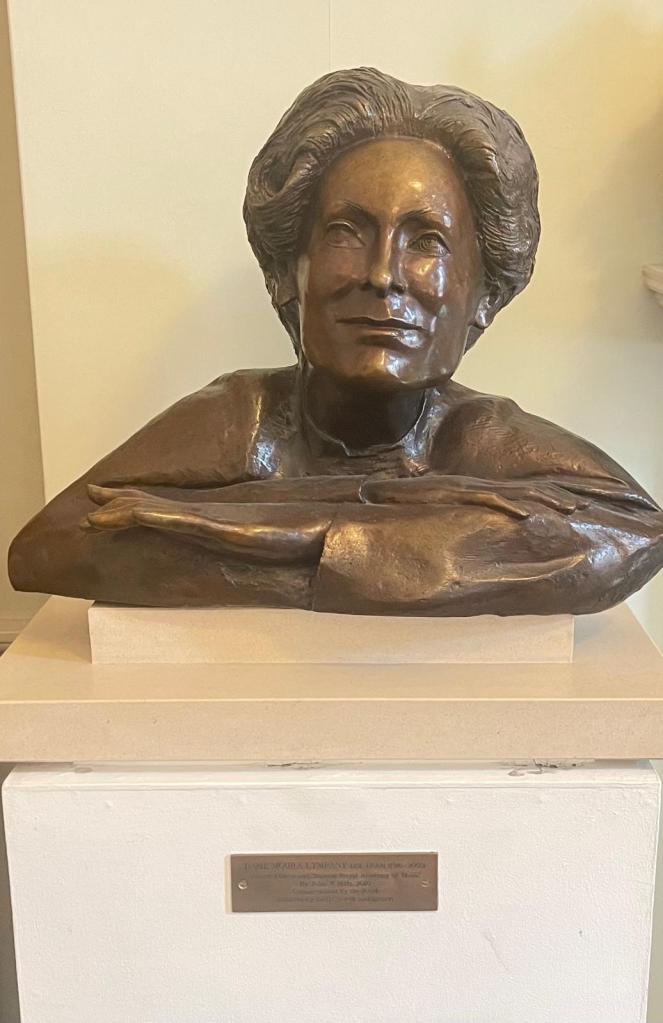

The greatest exponents for Uncle Tobbs ( as he was affectionately known) were another two remarkable women pianists : Dame Myra Hess and Dame Moura Lympany.

Listening to such mastery and dedicated musicianship today, Nina Tichman joins their ranks as an equally illustrious exponent of a school where above all the piano is allowed to sing with the same subtlety as the human voice.

A performance of unusual beauty where Nina allowed the variations to unfold with a refined palette of sounds of extraordinary noble expressiveness. Not projecting the music out to us in this vast hall but miraculously drawing us in to share in the wonders that were being created before our very eyes. Sharing these ingenuous variations with a beauty bathed in intelligence and refined good taste as they were never given a hard ungrateful edge. An ornamentation that was so natural that it could almost pass unnoticed such was it part of the world that Nina inhabited today.Even the 16th variation which heralds the half way mark was played with the elegance of a French overture of it’s time. The twenty ninth too usually played as a gymnastic exercise, where many add deep bass notes, but that Nina allowed to speak for itself as being the culmination of all that had gone before. Busoni of course needed to finish with the glory to God on High (and himself) and his edition from the 16th onwards reads like Liszt studies and a Tchaikovskian 1812 finish in glory. Nina played it with the respectful beauty and nobility of the Genius of Köthen .The ‘Quodlibet ‘ where Bach combines two popular tunes unfolded with unusually refined colouring. Out of the absolute silence after the final chord of the Quodlibet the aria was heard wafting into the refined air of the radiance and beauty that had been created by Nina in an hour an half of concentrated mastery.

Evolving , on Bach’s genial ground bass, with a naturalness that would have had Count Kesserling counting sheep that had at last found safety grazing in the bedroom of an insomniac !

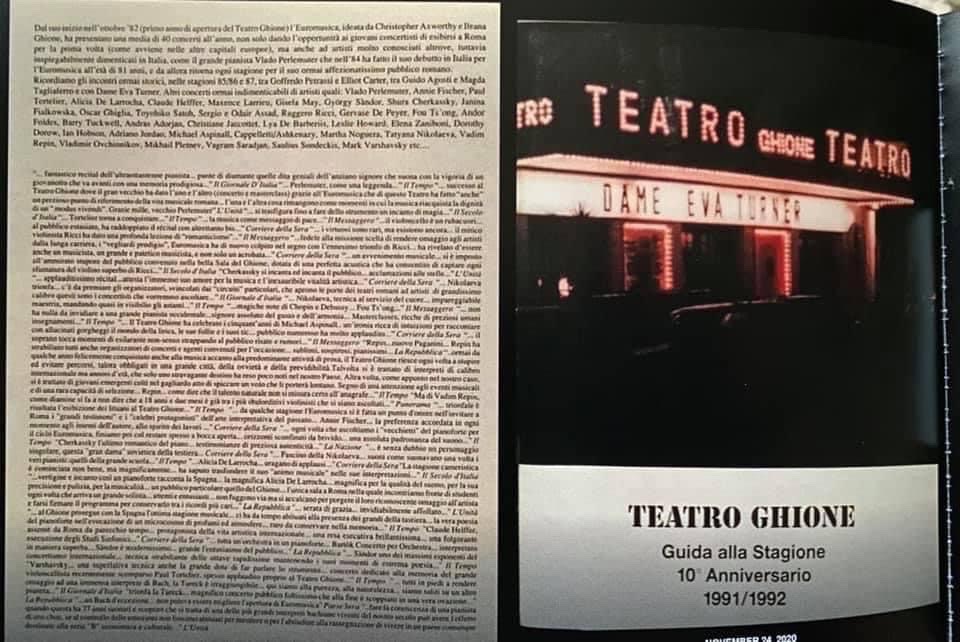

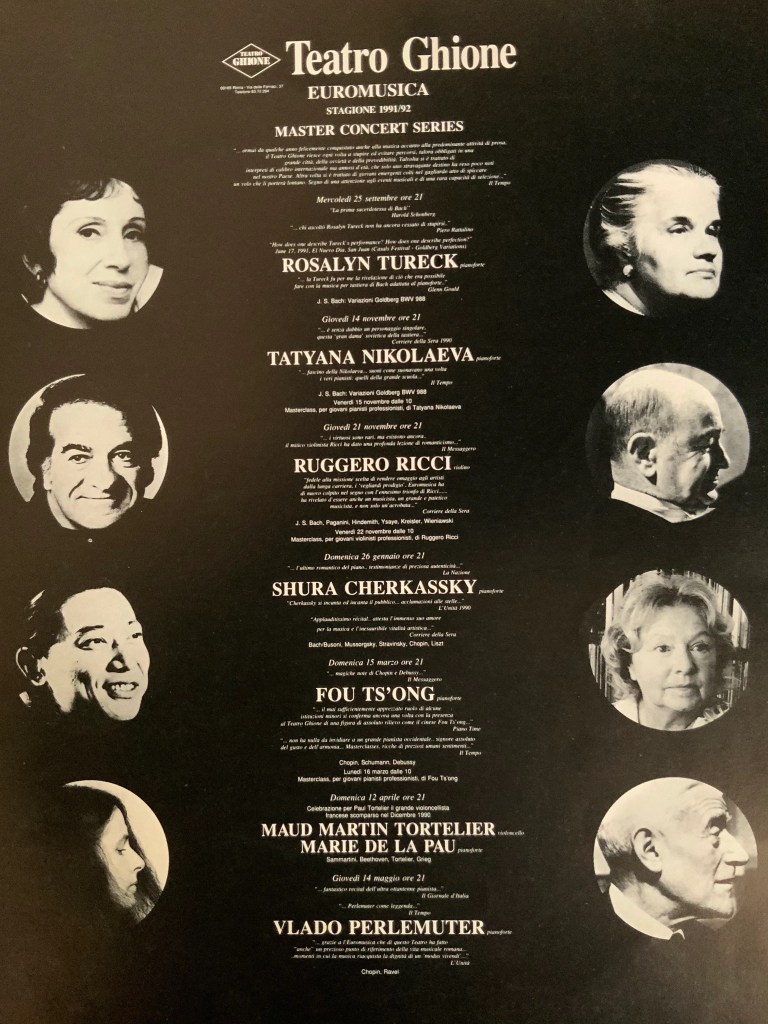

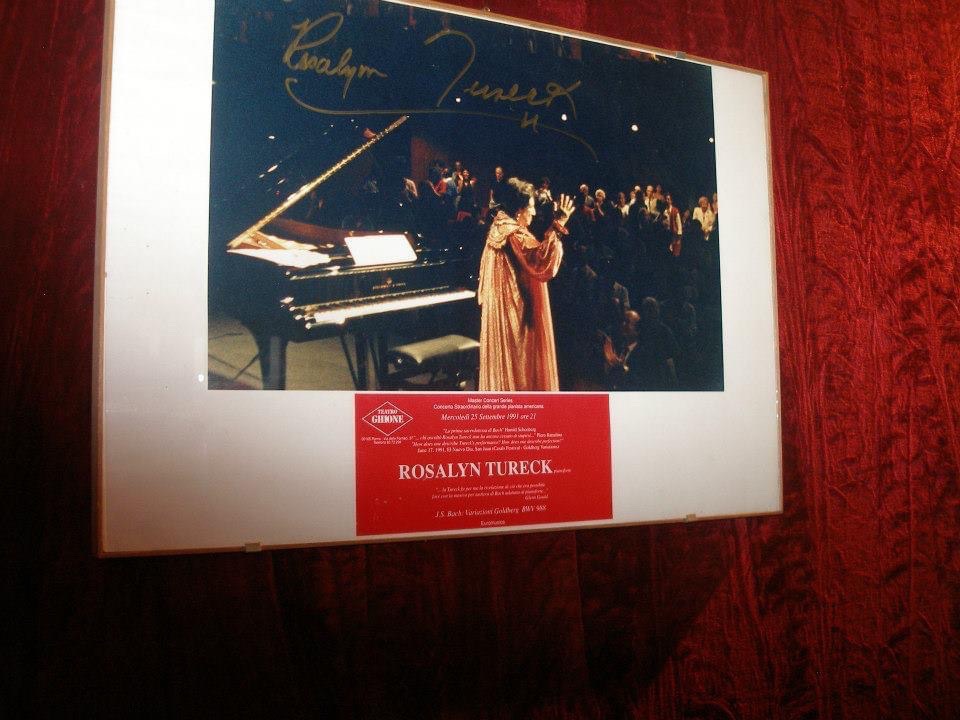

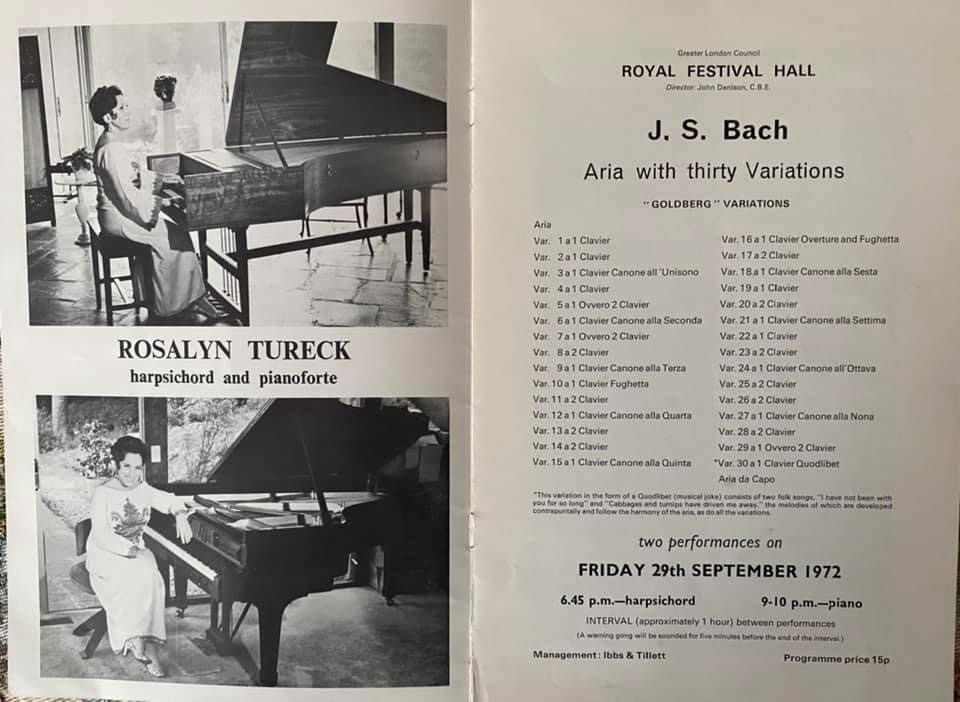

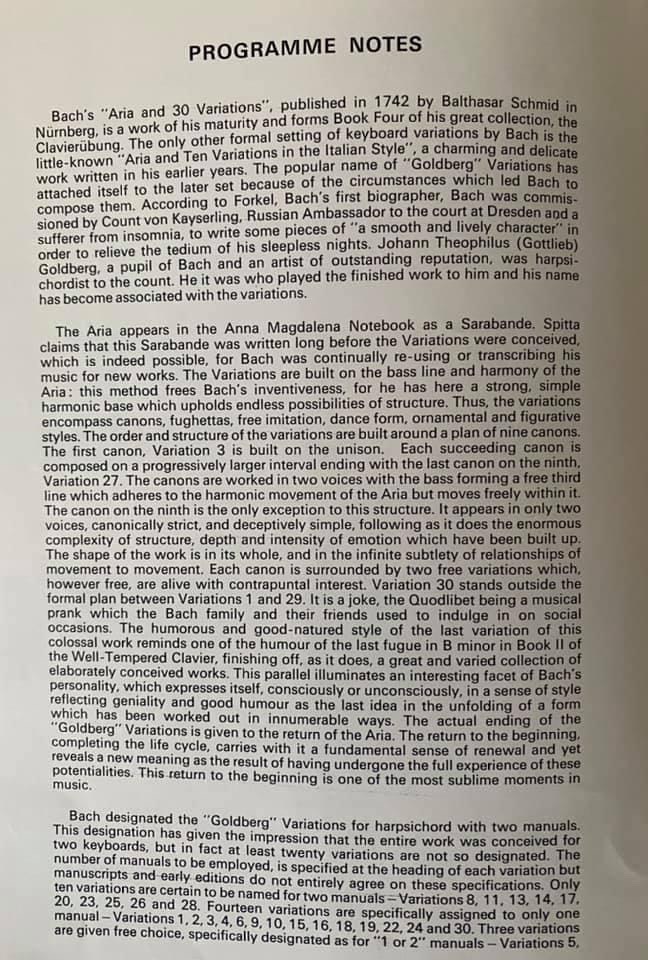

It was in 1991 that my great adventure with the Goldbergs began when I managed to persuade the High Priestess of Bach to leave the archives in Oxford and return to the concert hall where she truly belonged. I also managed to persuade Tatyana Nikolaeva to play the same variations a month later and was much criticised for not having more varied programmes! Rosalyn’s was a monumental Bach carved in stone whereas Nikolaeva was of the song and dance of simple people. I include below Rosalyn Tureck’s own fascinating programme notes for her double performance of the Goldbergs in London in 1972, that gave me the courage to ask her to perform again in public.

“Awesome” and “thrilling” ** are two of the adjectives used to describe Nina Tichman´s performances of Claude Debussy. In New York City, Frankfurt and other cities in Europe and the United States she held audiences spellbound with her traversal of the complete works in three evenings and her CDs with this repertoire have been called “because of her exquisite touch – the most beautiful recording of the complete works”.***

Since her debut at the age of seventeen playing Beethoven´s „Emperor Concerto“ Nina Tichman has appeared in the musical centers of the world such as New York´s Carnegie Hall, the Philharmonie in Cologne, the Konzerthaus in Berlin and the Festspielhaus in Salzburg, to name only a few. Acclaimed as “one of the leading pianists of her generation”****, she is at home in repertoire ranging from Frescobaldi to composers writing today, many of whom have entrusted her with world premieres of their compositions. Her discography includes music by Bartók, Beethoven, Copland (complete), Chopin, Corigliano, Debussy, Fauré, V.D. Kirchner, Krenek, Mendelssohn, Penderecki, und Reger. Her recording of the Complete Piano Works was hailed as a milestone in Debussy interpretation.

American born, Nina Tichman has been based in Europe since winning the prestigious “Busoni” Competition. Other awards include the Mendelssohn Prize of Berlin, First Prize of the Casagrande Competition in Italy and the Prize of the Organization of American States. She has appeared as soloist with orchestra and in recital in the major music centers of the world and has been featured in radio and television portraits on five continents. Her diverse activities as recitalist, chamber musician and pedagogue have led to invitations to perform and teach in festivals such as Marlboro, Tanglewood, Music from Salem, Styriarte, International Musicians Seminar at Prussia Cove, Frankfurt Feste, Rheingau Musikfestival, Beethoven Festival Bonn.

Nina Tichman is a graduate of The Juilliard School, where she was awarded the Eduard-Steuermann-Prize for outstanding musical achievement. In 1993 she was appointed Professor of Piano at the Hochschule für Musik in Cologne and she has led master classes at Amherst College, Princeton University, IKIF in New York, the Europäischen Akademie für Musik und Darstellende Kunst in Montepulciano, Holland Music Sessions and at the “Mozarteum” in Salzburg

Concert tours in the last years have taken her to China, Japan, Southeast Asia, Scandinavia, Greece, Turkey, Israel, New Zealand, Mexico, the United States as well as almost all European countries.

Highlights of the 2019/20 season include performances of the last three Beethoven Piano Sonatas as well as the continuation of a cycle of the complete Schubert Sonatas.

* New York Times ** Chelseas News *** Darmstädter Echo **** Neue Musik Zeitung *****Saale-Zeitung

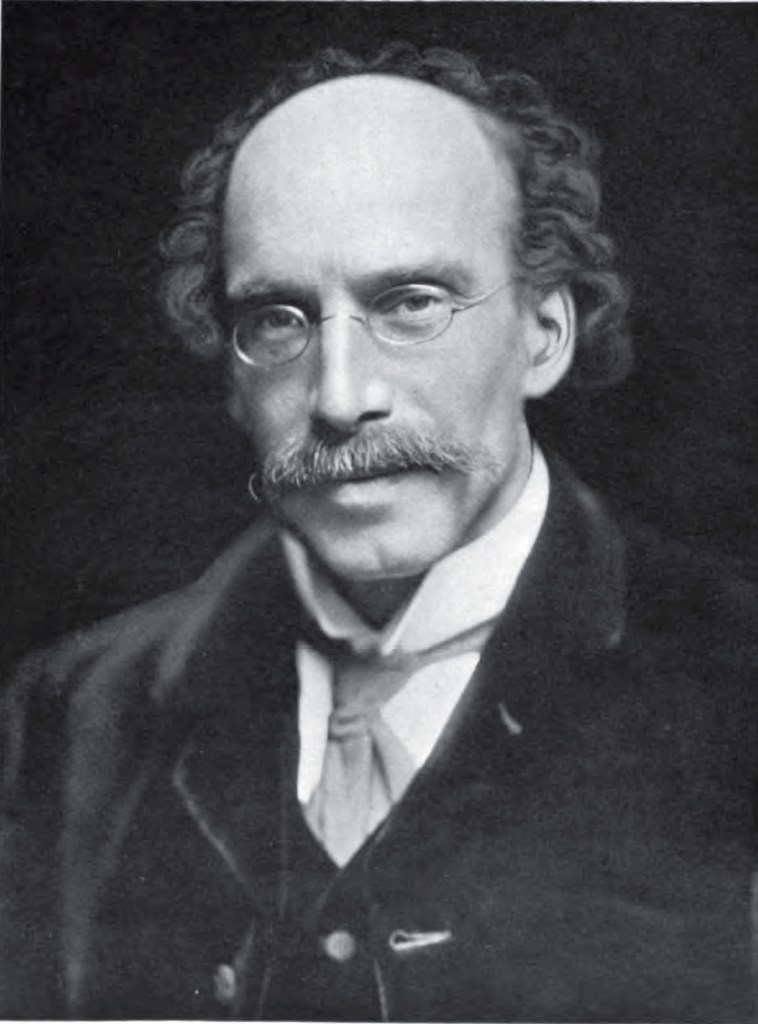

Tobias Augustus Matthay (19 February 1858 – 15 December 1945) was an English pianist , teacher, and composer.

Matthay was born in Clapham ,Surrey, in 1858 to parents who had come from northern Germany and eventually became naturalised British subjects. He entered London’s Royal Academy of Music in 1871 and eight months later he received the first scholarship given to honour the knighthood of its principal, Sir William Sterndale Bennett .At the academy, Matthay studied composition under Sir William Sterndale Bennett and Arthur Sullivan , and piano with William Dorrell and Walter Macfarren . He served as a sub-professor there from 1876 to 1880, and became an assistant professor of pianoforte in 1880, before being promoted to professor in 1884. With Frederick Corder and John Blackwood Mc Ewen, he co-founded the Society of British Composers in 1905. Matthay remained at the RAM until 1925, when he was forced to resign because McEwen—his former student who was then the academy’s Principal—publicly attacked his teaching.

In 1903, after over a decade of observation, analysis, and experimentation, he published The Act of Touch, an encyclopedic volume that influenced piano pedagogy throughout the English-speaking world. So many students were soon in quest of his insights that two years later he opened the Tobias Matthay Pianoforte School, first in Oxford Street, then in 1909 relocating to Wimpole Street, where it remained for the next 30 years. The teachers there included his sister Dora. He soon became known for his teaching principles that stressed proper piano touch and analysis of arm movements. He wrote several additional books on piano technique that brought him international recognition, and in 1912 he published Musical Interpretation, a widely read book that analyzed the principles of effective musicianship. However, whilst acknowledging its importance, a later interpreter of Matthay’s writing criticized its lack of clarity:

‘The interminable repetitions, recapitulations, summaries, footnotes, all with a change of emphasis and as often as not with new names for the same thing, led enquirers into a maze from which only the clearest brain equipped with a dogged perseverance, could extricate itself.’

Many of his pupils went on to define a school of 20th century English pianism, including Arthur Alexander ,York Bowen,Hild Dederich,Norman Fraser,Myra Hess, Denise Lasimonne, Clifford Curzon,Harold Craxton,Moura Lympany,Gertrude Peppercorn,Ruth Roberts,Irene Scharrer, Lilias Mackinnon, Guy Jonson, Vivian Langrish, Hope Squire,Eileen Joyce, jazz “syncopated” pianist Raie Da Costa, Harriet Cohen,Dorothy Howell,, and the duo Bartlett and Robertson . He taught many Americans, including Ray Lev, Eunice Norton , and Lytle Powell, and he was also the teacher of Canadian pianist Harry Dean, English composer Arnold Bax and English conductor Ernest Read. In 1920, Hilda Hester Collens, who had studied under Matthay from 1910 to 1914, founded a music college in Manchester named the Matthay School of Music in his honour. It was later renamed the Northern School of Music , a predecessor institution of the Royal Northern College of Music.

His wife Jessie née Kennedy, whom he married in 1893, wrote a biography of her husband, published posthumously in 1945.

This work is in the public domain in the United States of America, and possibly other nations. Within the United States, you may freely copy and distribute this work, as no entity (individual or corporate) has a copyright on the body of the work.

Scholars believe, and we concur, that this work is important enough to be preserved, reproduced, and made generally available to the public. To ensure a quality reading experience, this work has been proofread and republished using a format that seamlessly blends the original graphical elements with text in an easy-to-read typeface.

We appreciate your support of the preservation process, and thank you for being an important part of keeping this knowledge alive and relevant.

Born in 1914, Dorothy Taubman was the founder of the Taubman Institute of New York and developed what became known as the internationally famous “Taubman Approach” to piano playing.

“Playing the piano should feel delicious”, said Taubman whose technique analyses the motions needed for virtuosity and musical expression. In its early days of development it built a reputation through its rate of success in curing playing injuries. It provoked controversy, however, by questioning the physiological soundness of some traditional methods of piano teaching.

“The body is capable of fulfilling all pianistic demands without a violation of its nature if the most efficient ways are used; pain,insecurity, and lack of technical control are symptoms of incoordination rather than a lack of practice, intelligence, or talent”, said Taubman whose methods were always founded on a fundamentally naturalistic approach.

Besides offering a rational, diagnostic system aimed at solving the musical and physiological problems of piano interpretation, the techniques Taubman pioneered allowed her to cure repetitive stress injuries related to piano playing, and generally to rehabilitate injured pianists. Her techniques have been successfully adapted to help with RSI sufferers in general, especially when caused by computer keyboards.

To quote pianist and teacher Thomas Mark: “The application of the Taubman movements to specific pianistic situations, such as leaps, octaves, arpeggios etc, is often brilliantly effective. Almost all pianists, even highly accomplished ones, can develop more perfect use of fingers hands and forearm, and consequently almost all pianists, injured or not, who have studied the Taubman Approach have improved, even transformed, their playing.”

Among her most successful work, Taubman was recognised for her work with Leon Fleisher who was forced to play with only one hand for many years due to a painful medical condition.

For many years, Taubman directed the Dorothy Taubman School of Piano at Amherst College in Massachusetts and was a former professor at the Aaron Copland School of Music and at Temple University. She famously said that “blaming the instrument is like saying that writer’s cramp is caused by the pencil”.

Taubman was born in the East New York section of Brooklyn on August 16, 1917. Her parents, Benjamin and Bertha, were Jewish immigrants from Russia; her father, a businessman, committed suicide after the stock market crashed in 1929. Taubman never graduated from college, but took courses at Juilliard and Columbia University and studied with the renowned pianist Rosalyn Tureck for a year. In her 20s, her son said, she decided her calling was to be a teacher, not a concert pianist.

Taubman directed the Dorothy Taubman Institute of Piano at Amherst College in Massachusetts from 1976 to 2002. She was formerly a professor at Temple University and at the Aaron Copland School of Music in Queens College, and was featured in numerous articles and interviewed in the Boston Globe, The New York Times, and the Los Angeles Times; and the Piano Quarterly, Piano and Keyboard, and Clavier magazines. Taubman was noted for her work with injured musicians. Her students include the American pianist Leon Fleisher,Edna Golandsky and Yoheved Kaplinsky..

Besides offering a diagnostic system aimed at solving the musical and physiological problems of piano interpretation, the techniques Taubman pioneered have been used therapeutically to treat repetitive strain injuries related to piano playing, and generally to rehabilitate injured pianists. Her techniques have been adapted to computer keyboard typing.

In 1938 she married Harry Taubman, a businessman in the men’s clothing industry and the younger brother of Howard Taubman, chief music and theater critic in the 1950s and 1960s for The New York Times. With Harry, she had one son, who is dean of the school of medicine and dentistry at the University of Rochester .She died from pneumonia on April 3, 2013 in Brooklyn, New York, at the age of 95.