Thomas Masciaga opened the Bechstein Young Artists Series with canons covered in flowers

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2025/02/02/thomas-masciaga-opens-the-bechstein-young-artists-series-with-canons-covered-in-flowers/

Evening concerts starting from 18 pounds with an exclusive bar available for drinks

A beautiful new hall that is just complimenting the magnificence of the Wigmore Hall and the sumptuous salon of Bob Boas.Providing a much need space for the enormous amount of talent that London,the undisputed capital of classical music,must surely try to accommodate

Here are some of the recent performances :https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2024/12/02/vedran-janjanin-at-bechstein-hall-playing-of-scintillating-sumptuous-beauty/ of a remarkable artist’

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2024/11/27/axel-trolese-at-bechstein-hall-mastery-and-intelligence-of-a-remarkable-artist/

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2025/03/25/diana-cooper-miracles-at-bechstein-hall/

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2025/02/05/yukine-kuroki-at-bechstein-hall-a-star-shining-brightly-with-genial-poetic-mastery/

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2025/02/16/federico-colli-triumphs-at-the-new-bechstein-hall-as-it-comes-of-age/

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2025/02/24/nikita-lukinov-conquers-the-bechstein-hall-with-masterly-music-making/

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2025/02/02/guy-johnston-and-mishka-momen-rushdie-conquer-bechstein-hall-in-the-name-of-beethoven/

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2025/02/09/donglai-shi-at-bechstein-hall-young-artists-series-with-playing-of-clarity-and-purity-of-a-true-musician/

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2025/01/19/phillip-james-leslie-debut-recital-at-the-long-awaited-rebirth-of-bechstein-hall/

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2025/02/16/dmitri-kalashnikov-at-bechstein-hall-canons-covered-in-flowers-of-poetic-mastery/

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2025/02/21/andrey-gugnin-at-bechstein-hall-the-pianistic-perfection-of-a-supreme-stylist/

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2025/02/23/jeremy-chan-young-artists-recital-at-bechstein-hall-intelligence-and-artistry-combine-with-words-in-music/

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2025/03/23/william-bracken-at-bechstein-hall-mastery-and-mystery-of-a-great-musician/

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2025/03/25/diana-cooper-miracles-at-bechstein-hall/

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2025/03/29/mihai-ritivoiu-at-bechstein-hall-with-mastery-and-musicianship/

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2025/03/30/mariamna-sherling-at-bechstein-hall-kissed-by-the-gods-with-beauty-and-poetic-artistry/

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2025/03/31/thomas-masciagas-return-to-bechstein-hall-with-authority-and-intelligence/

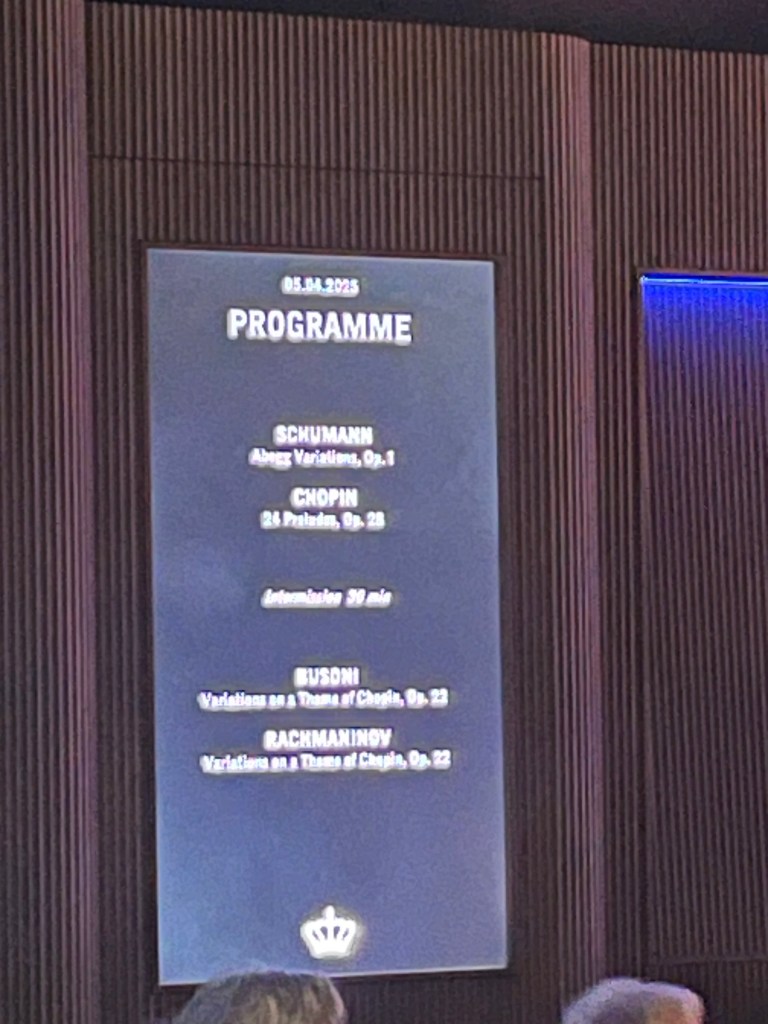

Peter Donohoe with a full house at Bechstein Hall and a fascinating programme based on Chopin’s C minor prelude op 28 . A second half with two sets of variations on that very prelude that Peter had played together with the other 23 in the first half.

SCHUMANN: Abegg Variations, Op. 1

CHOPIN: 24 Preludes, Op. 28

Intermission

BUSONI: Variations on a Theme of Chopin, Op. 22

RACHMANINOV: Variations on a Theme of Chopin, Op. 22

Variations by Busoni and Rachmaninov both coincidentally their op 22 .

The concert had begun with Schumann’s op 1 Abegg Variations played with a jeux perlé of beguiling charm and rubato that made this Bechstein glow with an intimate warmth.The starlit ceiling seemed to shine ever more like will o’the wisps with the fleeting charm that the youthful Schumann could exert on his lady admirers. Peter too played with a fluidity and subtle kaleidoscope of sounds that belong, all too often, to a past age.

The Chopin Preludes ,a new work to Peter’s repertoire, and if they did not yet have the same familiarity as the Schumann each one was sculptured in marble full of individual character and deeply contemplated emotions.The deep brooding of the second with the disarming simplicity of the shortest, the seventh, with its fleeting gasps of seeming innocence. It followed the mellifluous third where the washes of sound in the left hand merely accompanied the simple radiance of the melody. There was a dramatic opening to the fourth and the sixth soon evaporating to ever more whispered sounds.

The long lines of the sumptuous eighth ( obviously a great inspiration to the earlier studies of Scriabin ) were sacrificed for the gasps of a heart that beat with such searing intensity throughout his interpretation. Ravishing jeux perlé of the tenth was with a sense of improvised ease after the majestic nobility of the ninth and the beautifully sung eleventh with its beguiling rubato. The twelfth so often played like a bull in a china shop was played with masterly lightness and an architectural shape that could add exhilaration without hardness. The thirteenth surely one of Chopin’s most original bel canto creations, was played with radiance and beauty.A glowing bel canto and left hand meanderings of poetic simplicity with a central episode with moments that touched the sublime . Dynamic pulsating and ferocity were soon spent as the fourteenth fell to one side to make way for the simple radiant beauty of the so called ‘Raindrop’ prelude. In Peter’s hands it became a real tone poem of poignant beauty. The sixteenth feared by all but the bravest was played with quite extraordinary mastery and clarity which could only have been more exhilarating with more participation from the pounding insistence of the left hand. A beautiful flowing tempo to the seventeenth where the deep bass notes from the opening were the anchor on which such radiance could flourish.The improvised cadenza, that is the eighteenth, was played with insinuating insistence but the nineteenth ( perhaps the most technically difficult of all twenty four) was rather too slow to allow us to imagine the Aeolian harp on which the bel canto can simply float. A very rude awakening for the C minor, that is to become so important after the interval, was played with extraordinary vehemence but allowed Peter to judge with great sensitivity each recurring layer of sound until it became a dying whisper, simply discharged with a single glowing chord.The twenty first was shaped with great beauty if a little too ponderous to allow the melody to breathe with simplicity.The twenty second with the great bass octave declaration was played rather too staccato instead of the legato line that Chopin so clearly indicates. It was played with great clarity but sacrificing the grandeur and nobility before the disarming pastoral simplicity of the twenty third. Peter played this with ravishing fluidity and delicacy before the final mighty twenty fourth. Again sacrificing grandeur and nobility for clarity and remarkable technical authority where Chopin quite clearly indicates long pedal notes. The last three imperious ‘D’s’, though, were played with the undeniable authority of a great pianist .

After the interval we were treated to two very unfamiliar works of which Peter is an authority. I well remember our old piano teacher Gordon Green telling me about a fellow student in Manchester who could play anything even the Busoni Piano Concerto. Gordon had studied with Egon Petri a pupil of Busoni and his enthusiasm for Busoni was contagious and was passed on to all his students, John Ogdon and Peter amongst many others.

Two works I have rarely heard in the concert hall and both were played with mastery and total conviction. A fluidity that was missing in the original Chopin op 28, but here in both works there was a kaleidoscope of colour and chameleonic changes of character. One could even sense Brahms in one of the Busoni variations and the quixotic lightness of Schumann. Both had a ‘fugato’ towards the end that Peter played with clarity, but in Busoni there was the unmistakeable atmosphere of impersonal intellect ,whereas in Rachmaninov, whatever he did, was tinged with his unmistakable Russian nostalgia.

Two masterly performances greeted by a full house with a standing ovation and Peter only too happy to play Chopin’s miraculous Prelude op 45 as a thank you on his auspicious debut at the Bechstein Hall.

Greeted by Lady Rose Cholmondeley and many distinguished guests who were in a hall that has the courage to invite great artists to play in London with such fascinating eclectic programmes.

The Nine Variations on a Chopin Prelude resulted from a substantial revision of a large set of Variations and a Fugue on the celebrated Prelude in C minor (Op 28 No 20), which Busoni wrote in 1884 at the age of eighteen. In 1922 he added an introductory fugato and reduced the number of variations from eighteen to ten for inclusion in the first edition of the Klavierübung (1922), and then reduced it further to nine (by dropping the ‘Fantasia’) for the second edition (1925). Its final pages consist of a ‘Scherzo finale’ in tarantella style with an ‘Hommage à Chopin’ in waltz rhythm as its middle section

1 April 1873 Semyonovo, Staraya Russa, Novgorod Governorate, Russian Empire

28 March 1943 (aged 69). Beverly Hills, California, U.S.

Rachmaninov’s Variations on a theme of Chopin, Op 22, emerged during one of his most productive periods, in the wake of the second piano concerto. It was in these years that he developed his own distinctive voice, which comes through clearly in this piece. Chopin’s well-known C minor prelude (No 20 from his set of 24 Préludes, Op 28) gave rise to a stylistic challenge: how to transform Chopin into Rachmaninov and was also Rachmaninov’s first large-scale piece for solo piano, exploring an wide range of pianistic elaborations of great technical difficulty .It was dedicated to the world-famous virtuoso piano teacher Theodor Leschetizky.

The simplicity of Chopin’s Prelude lends itself to use as a variation theme and Rachmaninov returned to Chopin’s original conception, in two phrases (the repetition of the second phrase was only at the behest of Chopin’s publisher). The enormous set of twenty-two variations falls into three distinct phases: 1-10, 11-18 and 19-22.

Rachmaninov premiered the Chopin variations himself in 1903, but the audience showed much more enthusiasm for his Op 23 Preludes, which he played in the same programme. This put doubts in Rachmaninov’s mind, and he gave performers options for shortening the piece; he would himself cut several variations when he felt his audience was restive.

8 June 1810,Zwickau ,Saxony 29 July 1856 (aged 46) Bonn

The Variations on the name “Abegg” was composed between 1829 and 1830, while as a student in Heidelberg, and published as his op 1 The name is believed to refer to Schumann’s fictitious friend, Meta Abegg, whose surname Schumann used through a musical cryptogram as the motivic basis for the piece. The name Meta is considered to be an anagram of the word “tema” (Latin). Another suggestion is Pauline von Abegg. Apparently, when he was twenty years old, Schumann met her and dedicated this work to her, as witnessed in Clara Schumann’s edition of her husband’s piano works.

The first five notes of the theme are A, B♭ (B), E, G, and G. This use of pitch names as letters was also used by Schumann in other compositions, such as his Carnaval .

It is composed of:Theme and 5 Variations.

Fryderyk Franciszek Chopin.

1 March 1810 Źelazowa Wola ,Poland 17 October 1849 (aged 39) Paris

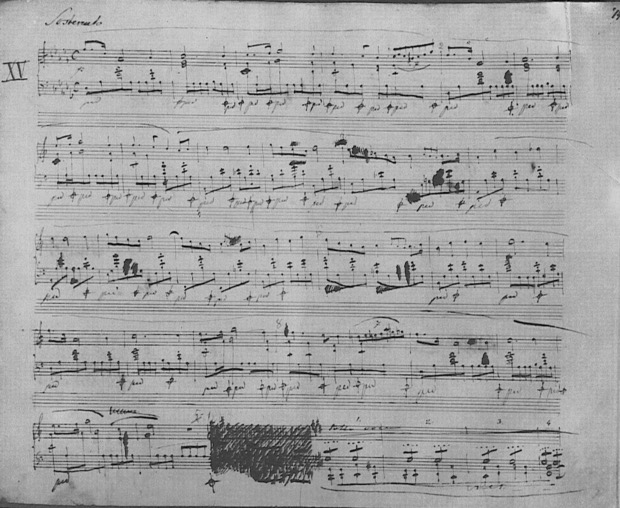

Chopin’s 24 Preludes op. 28, are a set of short pieces for the piano, one in each of the twenty-four keys , originally published in 1839. He wrote them between 1835 and 1839, mostly in Paris, but partially at Valldemossa,Mallorca, where he spent the winter of 1838–39 and where he, George Sand , and her children went to escape the damp Paris weather. In Majorca, Chopin had a copy of Bach’s ’48’, and as in each of Bach’s two sets of Chopin’s Op. 28 set comprises a complete cycle of the major and minor keys, albeit with a different ordering. Whereas Bach had arranged his collection of 48 preludes and fugues according to keys separated by rising semitones, Chopin’s key sequence is a circle of fifths, with each major key being followed by its relative minor , and so on (i.e. C major, A minor, G major, E minor, etc.). Since this sequence of related keys is much closer to common harmonic practice, it is thought that Chopin might have conceived the cycle as a single performance entity for continuous recital of his préludes .Chopin himself never played more than four of the preludes at any single public performance. Nor was this the practice for the 25 years after his death. The first pianist to program the complete set in a recital was probably Anna Yesipova for a concert in 1876. Nowadays, the complete set of Op. 28 preludes has become repertory fare, and many concert pianists have recorded the entire set, beginning with Ferruccio Busoni in 1915, when making piano rolls for the Duo-Art label. Alfred Cortot was the next pianist to record the complete preludes in 1926.

They were actually already finished before setting foot on Majorca, however, he did finalize them there, as referenced by him in his letters to Pleyel: “I have finished my préludes here on your little piano[…]”

The manuscript, which Chopin carefully prepared for publication, carries a dedication to the German pianist and composer Joseph Christoph Kessler. The French and English editions (Catelin, Wessel) were dedicated to the piano-maker and publisher Camille Pleyel, who had commissioned the work for 2,000 francs (equivalent to nearly €6500 in present-day currency). The German edition of Breitkopf & Härtel was dedicated to Kessler, who ten years earlier had dedicated his own set of 24 Preludes, Op. 31, to Chopin.

Fou Ts’ong called them 24 problems such are their quicksilver technical and poetic challenges

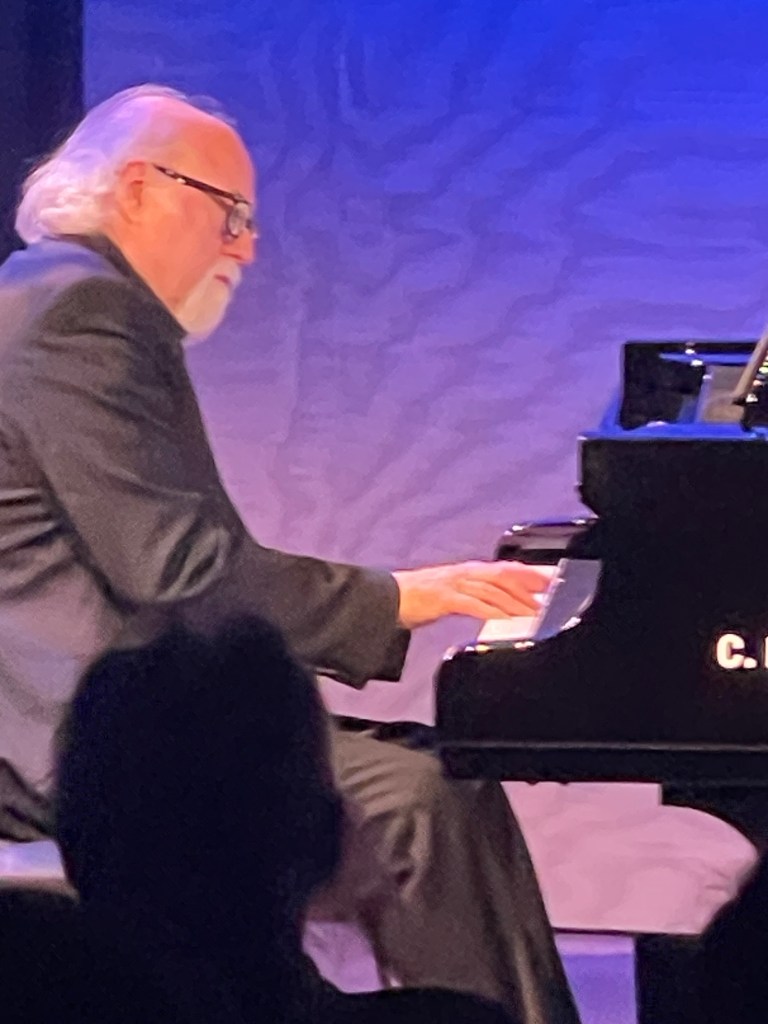

Peter Donohoe is in high demand as a jury member for major international competitions, including the Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow, Queen Elisabeth Competition in Brussels, Hong Kong International Piano Competition and the Artur Rubenstein Piano Competition. Peter Donohoe is one of the UK’s most respected and sought-after pianists; we are honoured to welcome him to Bechstein Hall

Peter Donohoe was born in Manchester in 1953. He studied at Chetham’s School of Music for seven years, graduated in music at Leeds University, and went on to study at the Royal Northern College of Music with Derek Wyndham and then in Paris with Olivier Messiaen and Yvonne Loriod. He is acclaimed as one of the foremost pianists of our time, for his musicianship, stylistic versatility and commanding technique.

In recent seasons Donohoe has appeared with Dresden Philharmonic Orchestra, BBC Philharmonic and Concert Orchestra, Cape Town Philharmonic Orchestra, St Petersburg Philharmonia, RTE National Symphony Orchestra, Belarusian State Symphony Orchestra, and City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra. He has undertaken a UK tour with the Russian State Philharmonic Orchestra, as well as giving concerts in many South American and European countries, China, Hong Kong, South Korea, Russia, and USA. Other past and future engagements include performances of all three MacMillian piano concertos with the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra; a ‘marathon’ recital of Scriabin’s complete piano sonatas at Milton Court; an all-Mozart series at Perth Concert Hall; concertos with the Moscow State Philharmonic Orchestra, St Petersburg Symphony Orchestra and the London Philharmonic Orchestraat Royal Festival Hall; and a residency at the Buxton International Festival.

Donohoe is also in high demand as a jury member for international competitions. He has recently served on the juries at the International Tchaikovsky Piano Competition in Moscow (2011 and 2015), Queen Elisabeth Competition in Brussels (2016), Georges Enescu Competition in Bucharest (2016), Hong Kong International Piano Competition (2016), Harbin Competition (2017 and 2018), Artur Rubenstein Piano Master Competition (2017), Lev Vlassenko Piano Competition and Festival (2017), Alaska International e-Competition (2018), Concours de Geneve Competition (2018), Ferrol Piano Competition (2022), and Hong Kong International Piano Competition (2022), along with many national competitions both within the UK and abroad.

Donohoe’s most recent discs include six volumes of Mozart Piano Sonatas with SOMM Records. Other recent recordings include Haydn Keyboard Works Volume 1 (Signum), Grieg Lyric Pieces Volume 1 (Chandos), Dora Pejacevic Piano Concerto (Chandos), Brahms and Schumann viola sonatas with Philip Dukes (Chandos), and Busoni: Elegies and Toccata (Chandos), which was nominatedfor BBC Music Magazine Award. Donohoe has performed with all the major London orchestras, as well as orchestras from across the world: the Royal Concertgebouw, Leipzig Gewandhaus, Munich Philharmonic, Swedish Radio, Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France, Vienna Symphony and Czech Philharmonic Orchestras. He has also played with the Berliner Philharmoniker in Sir Simon Rattle’s opening concerts as Music Director. He made his twenty-second appearance at the BBC Proms in 2012 and has appeared at many other festivals including six consecutive visits to the Edinburgh Festival, La Roque d’Anthéron in France, and at the Ruhr and Schleswig Holstein Festivals in Germany.

The 23/24 season kicked off with Peter Donohoe performing as a soloist with the London Symphony Orchestra and Simon Rattle with four performances of Messiaen’s Turangalîla-Symphonie in London, Edinburgh, and Bucharest. In January 2024, Peter returns to Philadelphia for performance with the Ama Deus Ensemble and will then travel to Dubai to adjudicate the 3rd Classic Piano Competition 2024.