I have heard Parvis play many times during his studies with Norma Fisher at the Royal College of Music but the pass from being a prize student to becoming an artist can be long and arduous. You have been given a superb training but this is just the beginning and the experience of playing in public and gaining confidence takes time and sacrifice. Most,having finished their scholarship programmes, have to augment the continuation of their artistic ideals with teaching, that can lead to having less time to spend at the keyboard and to prepare programmes. Parvis seems to be an exception to this rule. As a student he was trying to run before he could walk, but his talent was always evident.Today I was very pleased to hear a rather lazy student become a serious artist. Parvis today played with impeccable preparation and authority and if anything he could now take more time and allow the music to unfold naturally allowing more freedom for his stylistic and undoubted poetic sensibility.

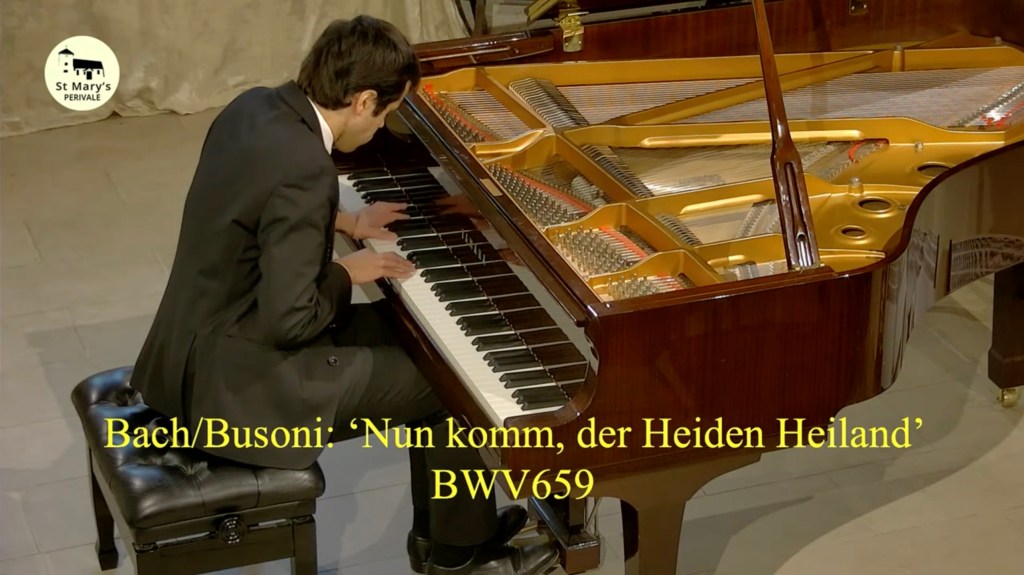

Two of the most beautiful of Busoni’s transcriptions of Bach Chorales were played with beauty and deeply felt sentiment. Sentiment that was never sentimental but of the aristocratic fervour of a true believer. There was a flowing line to ‘Nun komm’ that at first seemed very slow but was so full of significance that it was totally convincing.

‘Ich ruf zu dir ‘ is one of the most beautiful of all Busoni’s reimaginings of Bach and I was reminded today of the much missed Nelson Freire who would always include it somewhere in his recitals in Rome together with Gluck/Sgambati : Melody from ‘Orfeo ed Euridice’. Parvis played it with a radiance and a beautiful wave of sounds on which he etched Bach’s glorious melodic invention, sustained by sumptuous bass notes that gave a monumental richness to the beauty that was unfolding from Parvis’s sensitive hands with poignant simplicity.

Nelson Freire RIP……the legacy of a great artist

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2021/11/02/nelson-freire-rip/

Beethoven’s penultimate sonata was played with remarkable technical and musical preparation where even the treacherous leaps in the ‘Trio’ of the ‘Scherzo’ were played with fearless abandon and authority. But as Parvis said in his very interesting and authoritative introductions:’ Is Beethoven a Classical or Romantic composer?’ Well let us not forget that his teacher, Haydn was the inventor of the symphony and inherited the musical forms of his age, bringing them to a new stage of genial invention, but they were mostly of the refined denial of his age. Beethoven took these early forms from his mentor and transformed them with genius, bringing them into a world of ‘Sturm und Drang’ where music could dig deep into the emotions and reveal things that words could never do. Parvis had seen Beethoven as classical and his performance could have had more time to breathe and be shaped with a style that is both classical and romantic. A beautiful opening to op 110, but after a rather prolonged trill suddenly the tempo changed and the ravishing beauty of the opening ( similar to the fourth piano concerto) gave way to a chase. Played with great mastery but lacking the ‘spiritual’ character of one of Beethoven’s gentlest late creations. Beethoven’s irascible contrasting temperament of sudden eruptions and abrupt changes are alien to this last sonata ( and also the one before op 109) giving way to a gentler more accommodating vision of life. Parvis, always playing with a very sensitive sense of balance and extraordinary clarity which suited more the ‘Scherzo’ than the ‘Moderato’ of op 110. The ‘Adagio’ was played with beautiful poise where Beethoven’s own pedalling give a luminous glow to the absolute clarity of the knotty twine that was unfolding. The great ‘Aria’, though, floating on a heart, beating intensely, missed the etherial magic of a composer who had come to terms with a difficult and turbulent life and could now envisage the paradise that was awaiting him only a few years later at the age of fifty seven.

Poulenc’s suave elegance and showmanship suited Parvis much better, as he gave great character to the infectious ‘joie de vivre’ and facade that Poulenc escaped to in his music. A capricious sense of humour to the ‘Très rapide’ was played with a rhythmic elan where Parvis could have been even more fancy free to enjoy the bucolic outpourings of a true Parisian entertainer of the 20’s and 30’s . Sumptuous golden beauty was part of Poulenc’s world too and the ‘Andante’ was bathed in a subtle radiance where Parvis allowed the music to unfold naturally, leading to the ending suspended in air, with a cadence that owed much to the freedom of jazz improvisations of the day.

The opening of Schumann’s ‘Carnaval Jest’ was like the Beethoven, rather breathless, with Parvis’s wish to show us the architectural shape of the opening ‘Allegro’ rather than risking taking a little more time to breathe. I remember a famous pianist friend playing the Schumann Concerto in Rome with a good but not well established ensemble. In the rehearsal she mentioned to the conductor that in various places she liked to breathe .Oh,my dear,he exclaimed, that is very dangerous! It is a risk, but one that I feel Parvis can now allow himself, seeking to be free from architectural constraints and to just turn corners with a little more self indulgence.The indulgence that he did bring to the ‘Intermezzo’, that he played with admirable passion and freedom, allowing the music to unfold with ravishing beauty of romantic intensity.The ‘Romance’ ,too, was played with disarming simplicity and beauty and the ‘Scherzo’ thrown off with admirable nonchalance and ease. There was a rhythmic drive to the finale but here, as in the first movement, the lyrical passages were not given the time that they needed to speak with Schumann’s unique voice – that of Eusebius the poet of his soul.

I had no idea that Parvis was also a composer, and so was impressed with his own improvisation on a Gregorian chant .Beautiful, subtle un constrained sounds, those that had been missing in the masterworks he was interpreting showing a little too much respect.

The notes on the page are only an indication of the sounds that are in the composers head. Beethoven,miraculously, when he was totally deaf, could still write exactly what was in his head to bequeath to posterity.

‘Je sens,je joue ,je trasmet’ is a motto that all interpreters should keep in their studio. Together with humility, respect and intelligence, it is the secret formula of all great artists and one that can open the door to a ‘Pandora’s Box’ of hidden secrets. A voyage of discovery shared with an audience is a unique experience and, as Gilels exclaimed :the difference between fresh food rather than canned!