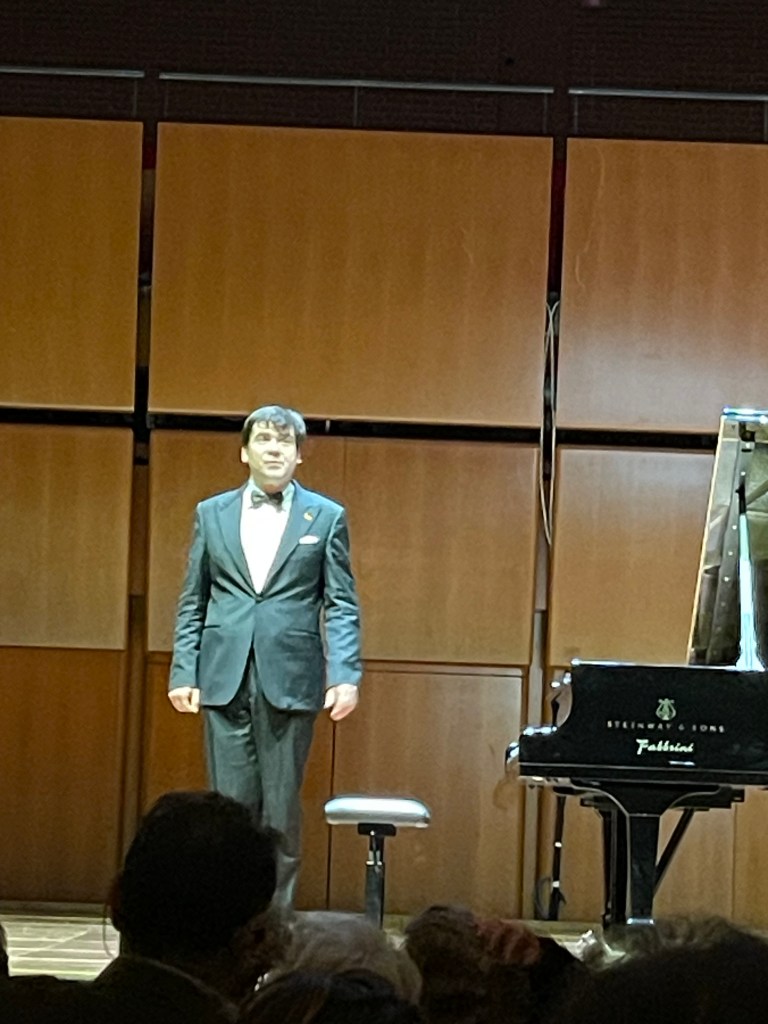

An indisposed Bronfman in Rome, and after Kholodenko’s recent success with Pappano of the Busoni Piano Concerto , it provided the ideal opportunity to be able to hear this 2014 Van Cliburn Gold Prize Winner in a programme of entirely his own making .

I have heard Vadim recently playing the Rzewski Variations in London and was completely won over by the kaleidoscopic range of sounds that he was able to find in a marathon work of transcendental difficulty that was commissioned by Ursula Oppens in 1975. In fact Ursula was in Siena in the class of Agosti in 1968 before going on to win first prize in the Busoni competition . A pianist much admired by Agosti for her respect for the composer’s wishes and her very intellectual and serious preparation of all the works she played. I remember Siena resounded to her continuous practicing of a Prelude by Busoni that was one of the set pieces that she had obviously decided to prepare in Siena. Her Chopin Fourth Ballade, her teacher Rosina Lhévinne had advised her never to play in public was praised to the skies by Agosti for its lack of adherence to tradition but total respect for what the composer actually wrote. Ursula now in her 80th year is a legendary figure amongst contemporary composer who she has been championing all her life. She has recorded the Rzerwski Variations twice since its commission in 1975. But it was Kholodenko who could add fantasy and colour that illuminated a rather intellectual score. He paired it in London with the transcription of the Mozart Requiem by Karl Klindworth ,a pupil of Liszt. And I remember that the strict construction of the Requiem was lost with Kholodenko’s searching for hidden sounds and colours instead of etching out the great architectural contour of such a masterpiece.

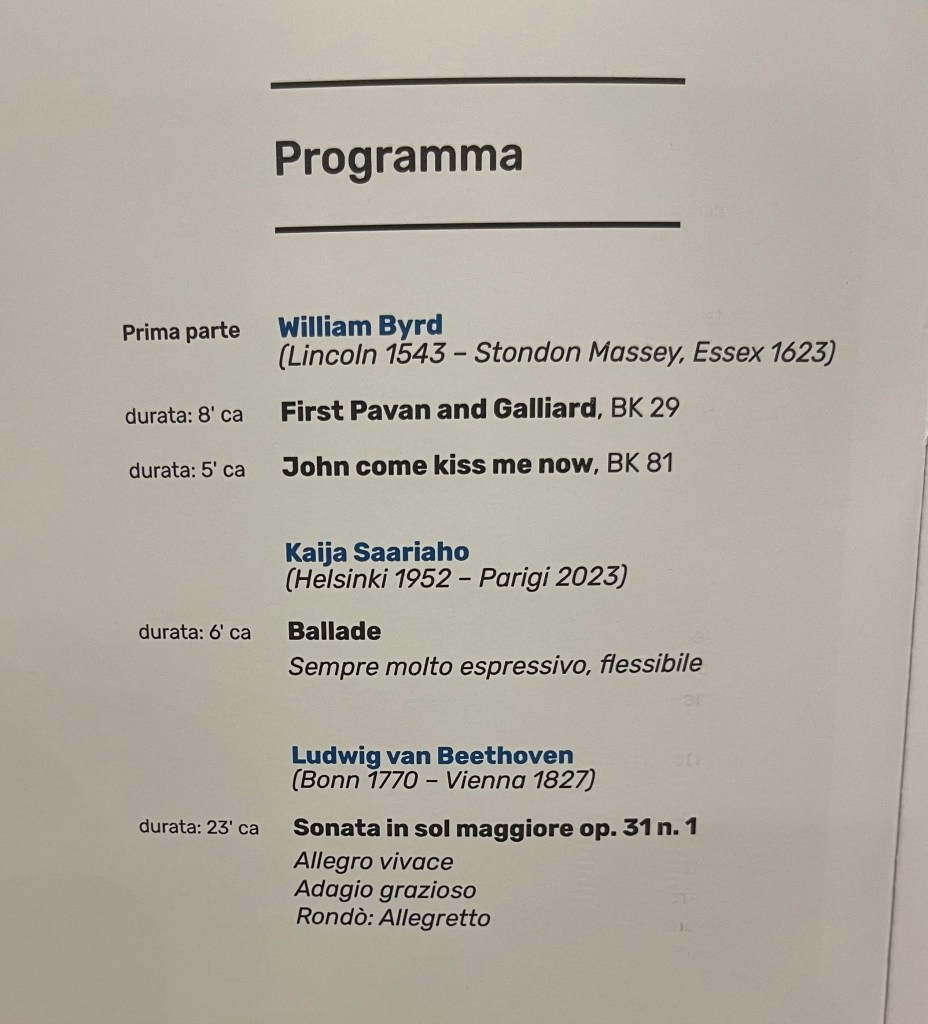

Today he had chosen three pieces to open the programme that demonstrated his extraordinary sense of colour and a range of sounds from pianissimo to mezzo forte that are remarkable. Byrd with its renaissance meanderings was an ideal way to prepare the audience for Kholodenko’s unique sound world. Sokolov has recently brought the Renaissance music into the concert hall, after the pioneering work of Glenn Gould, with works by Purcell and Byrd. Sokolov,though,was able to bring a sense of line and architectural shape to these works written for keyboard instruments where colour and variety were provided by the change of manuals and ornamentation. Kholodenko brought us into a sound world that was the same as the contemporary Saariaho’s Ballade which was played without a break after the Byrd. A world of wondrous whispered sounds, but music is made of the song and the dance and it is this sense of rhythm or pulse that creates an architectural line giving order to the sounds, however magical that are being produced.

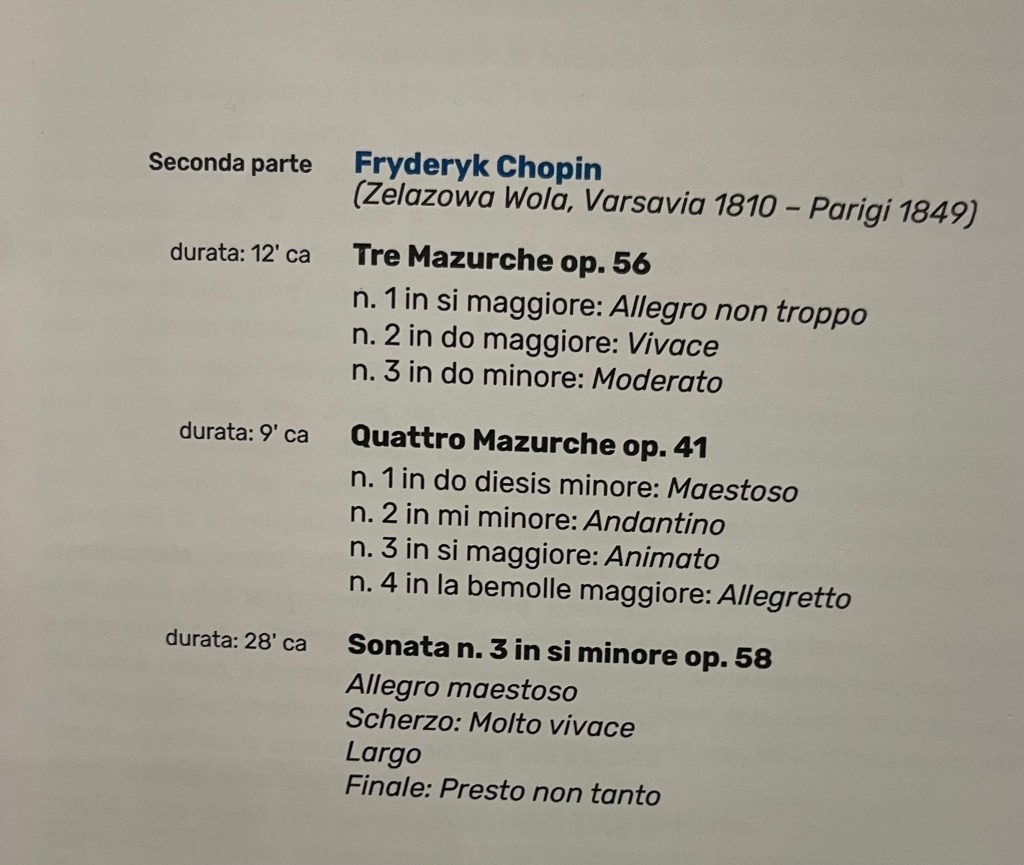

This was the world of Kholodenko that was to pervade the whole of his programme. Even the miniature tone poems that are Chopin’s Mazurkas were treated to sounds and beguiling whimsical half lights, but the overall shape of these ‘canons covered in flowers’ was sacrificed for a palette of sounds that had a momentary pleasing effect but sounded more as though they were a personal gratification rather than an interpretation of what the composer had written in the score. An improvised freedom that in the hands of a true servant of the composer becomes a freedom as one discovers the inspiration that was behind the notes that were still wet on the page. But to take the notes of the composer and use them for a free improvisation is something that the pianists of the 19th century used to do as they discovered more and more the possibilities of a instrument with touch and pedals. De Pachman would talk to the public to tell them about the wonders he was producing from a box with strings and hammers. Anton Rubinstein described the pedals as being the ‘soul’ of the piano. These were artists that excelled in miniatures of whispered asides contrasted with bombastic showmanship. Liszt and Thalberg had a pianistic duel to decide who was the better of the greatest pianists before the aristocratic audiences of the day. They had invented the three handed pianistic technique of allowing a melody to be sustained by the pedal with the melody shared between alternating hands while notes were awash all around the keyboard. A pianist of the calibre of Artur Schnabel was to appear on the scene ,who even his teacher Leschetizky said that he was not a real pianist. It was Schnabel himself who said that usually the programmes of pianists of the day were with a serious,boring first half and and crowd pleasing second.His programmes were with both halves equally boring!

I was hoping that Kholodenko with masterpieces such as Beethoven’s Sonata op 31 n. 1 and Chopin’s B minor sonata that have such an architectural shape would be where Kholodenko’s palette of colours could illuminate and bring fresh life to such well know and often played works. On this occasion Kholodenko was in contemplative mood and the Beethoven suffered from a lack of shape and became a series of disjointed episodes where Beethoven’s continuous undercurrent of rhythmic pulse was sacrificed for colourful episodes and a continual change of tempo disturbing the very structure of Beethoven’s edifice. Nowhere was it more apparent, though, than in the Chopin B minor Sonata.The second subject of the first movement was slowed down and played as a delicate nocturne having been prepared for by a cloud of delicate filigree notes that completely lost the sense of structure of this monumental work.The Scherzo was played like a charming encore piece of glistening bravura ,juggling notes , and the opening of the rondò with whispered insinuation bore no resemblance to what Chopin had indicated.

Two Bagatelles by Beethoven were encores that Kholodenko generously offered to this rather small audience and they ideally suited his mood today .They were played with bewitching colour and the same whimsical fantasy with which Beethoven had penned them to please a public that often thought his music was too long and serious for their taste !

Jed Distler writes of the 2023 London Piano Festival performance:

Boundaries between ideation and execution do not exist for Vadym Kholodenko. He can do whatever he pleases on the piano, and his interpretations, like them or not, draw attention to that fact. To be sure, his kaleidoscopic shades, half tints and boundlessly nuanced voicings in Handel’s Suite in B-flat HWV 434 will cause Baroque purists to squirm, yet they are catnip for piano connoisseurs. Haydn’s C-sharp Minor Sonata Hob. XVI:36 unfolded with similar pianistic orientation. In Beethoven’s Sonata No. 27 in E Minor Op. 90, Kholodenko’s penchant for arpeggiating left hand chords grew increasingly predictable and without purposeful intent in the first movement, while his animatedly glib Finale bounced through one ear and out the other.

Still, Kholodenko’s total independence between hands and multi-leveled separation of melody and accompaniment must be acknowledged. So does his ability to toss off octave passages in both the Liszt Dante Sonata and Tarantella with more speed, suavity and proficiency than most pianists can handle single notes. Kholodenko also is fond of playing rapid decorative passages in tempo. Such technical feats, however, ultimately amount to tricks, drawing attention away from the music’s drama, dynamism and raving harmonic genius. By contrast, the disarming simplicity of Silvestrov’s Bagatelles Op. 1 and the complex, leisurely unfolding textures through Thomas Adès’ Traced Overhead easily absorbed the pianist’s one-size-fits-all interpretive game plan. In sum, this rather odd assemblage of works added up to a pianistic version of a line from a Leonard Bernstein song: “I hate music, but I love to sing.”