https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2024/11/10/giovanni-bertolazzis-spellbinding-mastery-ignites-and-excites-roma-3-orchestra/

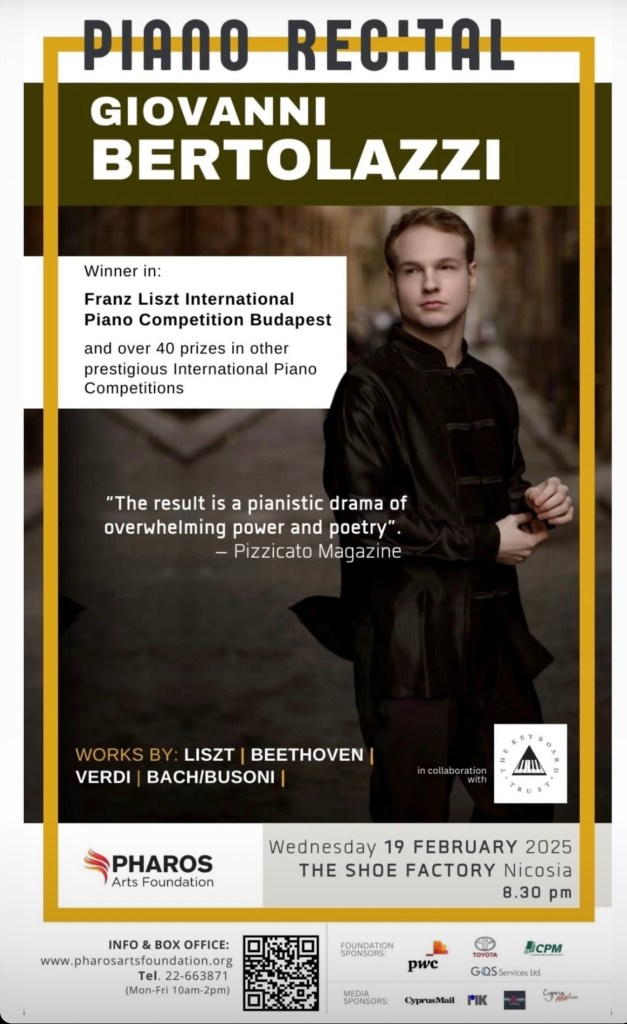

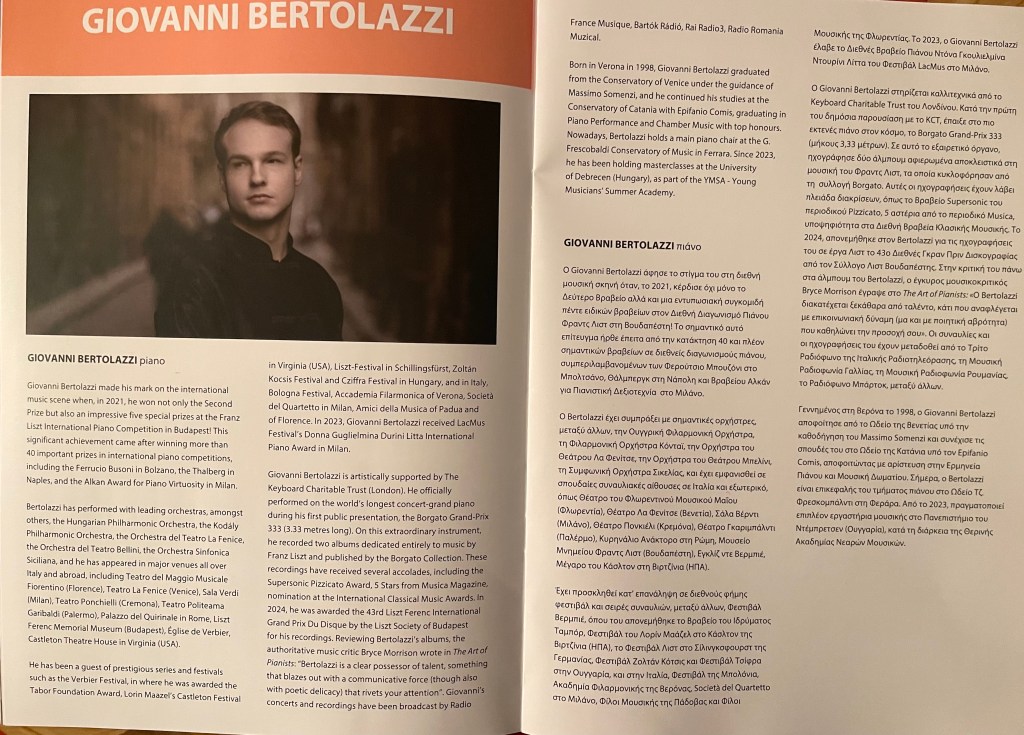

Some remarkable playing at the Pharos Arts Foundation from the young Italian virtuoso Giovanni Bertolazzi. A programme that ranged from the imperious nobility of the Bach Chaconne through the driving intensity of Beethoven’s Waldstein Sonata to Liszt’s ravishing revisitation of Verdi and his funabulistic vision of Dante.

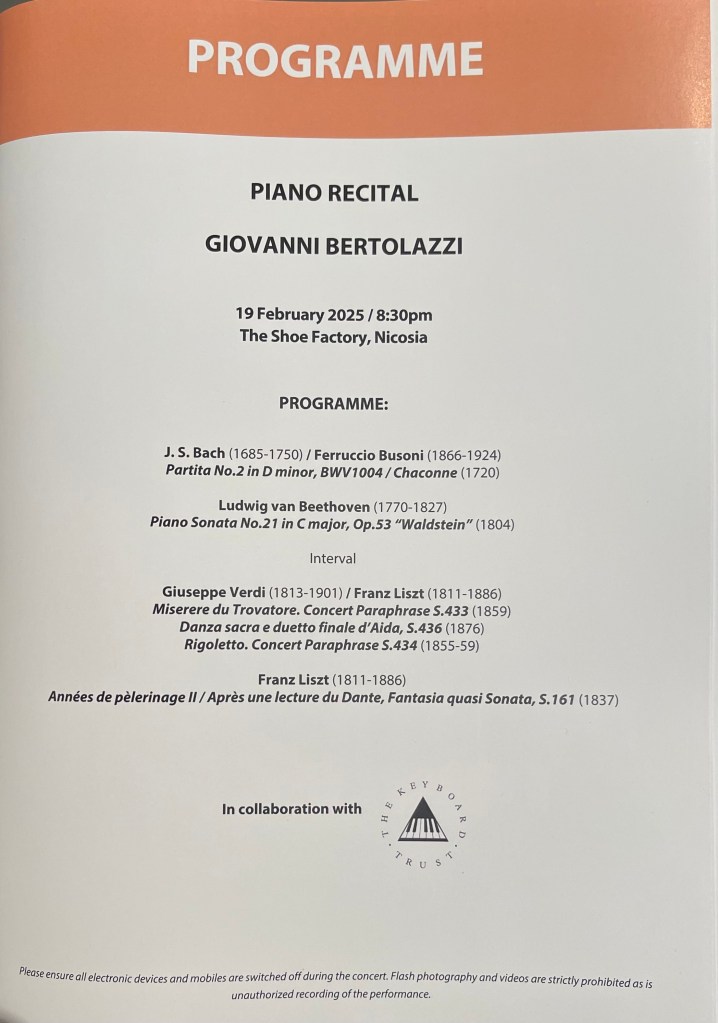

Fearless dynamic drive and power was contrasted with ravishing beauty and whispered seduction from a pianist who has a story to share with intelligence and mastery.The Bach Chaconne in Busoni’s miraculous ‘elaborazione concertistica per pianoforte a due mani’, immediately opened with nobility and breathtaking authority. There were dramatic contrasts from the imperious to the almost expressionless innocence with a quite extraordinary command of the keyboard and of the three pedals. A technical mastery that allows him to play the left hand octaves with lightweight ease without ever having to accommodate the surge of inner energy that Bach’s genius could incorporate on a single violin line.The whispered repeated notes between the hands ‘tranquillo’ and ‘subito piano’ had just as much impact as the mighty fortissimo passages that followed .There was a masterly control that could pass from one layer of sound to another. ‘Quasi tromboni’, Busoni writes and Giovanni finding a heartrending richness at the beginning of the build up to the mighty climax and the final glorious declamation ‘largamente maestoso’ with the blaze of glory that Busoni brings to this Chaconne with devastating effect. Giovanni entering into this world of majesty and nobility with authoritative abandon on this magnificent instrument and if sometimes the bass notes were overpowering it was the energy behind the notes that enthralled and astonished an audience that had not expected such youthful mastery from the very first notes.

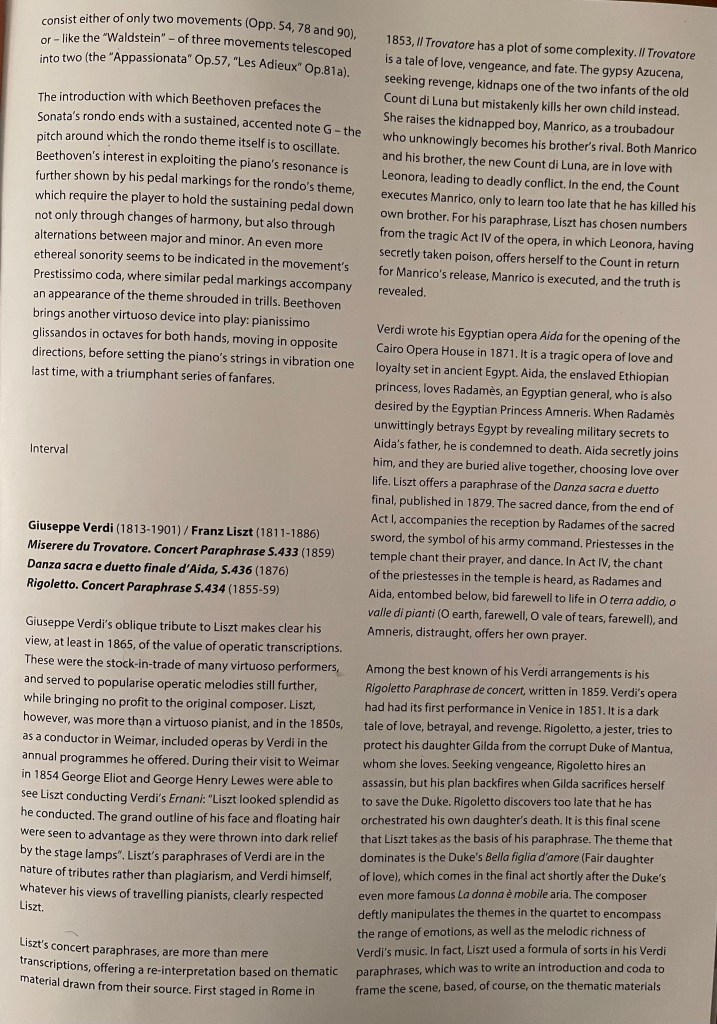

The ‘Waldstein’ Sonata together with the ‘Emperor’ concerto are both from Beethoven’s ‘middle ‘ period and one can see why Delius dismissed Beethoven with ‘all scales and arpeggios’, Bach he simply dismissed as ‘knotty twine’.There is an element of truth ,though, because the ‘Waldstein’ has a driving intensity and burning rhythmic drive in the first and last movements that needs a transcendental mastery to be able to maintain the undercurrent of surging energy. It also needs intelligence to be able to interpret Beethoven’s very meticulous indications. Giovanni has both the technical mastery and also the intelligent musicianship that allows him to maintain the tempo of the first movement, taking the opening tempo from the mellifluous second subject so there is no sickly slowing down where Beethoven combines strength with beauty.This first movement is a series of electric shocks with the opening like a wind that every so often erupts with Beethoven’s irascible impatience and without warning. It was with these contrasts that we could appreciate Giovanni’s intelligent musicianship and absolute respect for the composers indications.Not just playing them because they are written in black and white on the page but understanding what the composers intentions were at the moment of creation. Remarkable finger legato in the final pages that allowed him to keep the burning rhythmic motif in the left hand with legato descending octaves in the right all pianissimo without pedal! The final few bars were also quite extraordinary with three isolated chords as if Beethoven was slamming the door in our face. The audience dared not breathe such was the state of shock provoked by Giovanni’s burning authority. Beethoven’s irascible character had silenced and mesmerised the audience as the solemn beauty of the ‘Adagio molto’ opened with orchestral nobility and a kaleidoscope of colour. ‘Rinforzando’ Beethoven writes and here Giovanni brought an intensity, building to a burning agitation that died away almost as soon as it was born, as Giovanni pointed with one outstretched finger to the top ‘G’ that was to be transformed into the magic opening of the Rondò. Beethoven’s long held pedal indications giving a pastoral feel to the undulating accompaniment of the rondò. The contrasting episodes were ever more exhilarating and virtuosistic with some extraordinarily masterful playing of relentless dynamic rhythmic energy. Gradually the majestic chordal declamations died away to a ‘pianississimo’ whisper suddenly to be awakened by an electric shock change of character that in Giovanni’s hands was truly startling.The ‘Prestissimo’ coda was played with remarkable brilliance and control with Beethoven’s glissando octaves first in the right hand and then the left played with a mastery that is not of all pianists on the pianos of today that have much more weight.The long pedals and Beethoven’s trills were played like streams of sound on which the bell like rondò theme could ring out with music box precision.

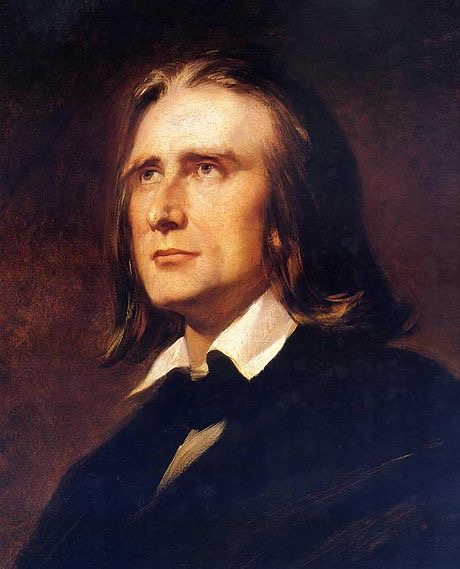

The second half of the concert was dedicated to Liszt who is a composer that is close to Giovanni’s heart. He was justly feted in the Liszt Academy with a top prize in the International Franz Liszt Piano Competition at the age of twenty two. The remarkable thing about his Liszt playing is his total identification with the sound world that the genius of Liszt could bring to the piano. I have heard him in Rome play all seven of the transcriptions and paraphrases that Liszt made of Verdi operas. Today he chose just three with the deep bass brooding of the ‘Miserere’ from il Trovatore where out of these dark sounds a ravishing melody emerges ever more elaborate played with a beguiling style and astonishing virtuosity. The ‘Rigoletto’ paraphrase is perhaps the most often played of these Liszt revisitations of Verdi. Giovanni played it with great style with swirls of notes with the so called ‘three handed piano playing’ that Liszt and Thalberg were to use with such extraordinary effect on pianos that now had a sustaining pedal that allowed a melodic line to be shared between the hands in the tenor register with swirls of notes all around. Giovanni brought a richness and beauty together with breathtaking pyrotechnics but also a bewitching sense of dance that was quite hypnotic in its charm and even daring.

But the most beautiful and strangely rarely played ‘Aida’ paraphrase was a revelation as the genius of Liszt combines with that of Verdi with mists of notes on which emerges the final ravishing duet of what is really a chamber opera of extraordinary intimacy.There may be the sacred dance music that Giovanni played with clockwork precision ( luckily Liszt did not add the Triumphal March ) but it was magic that illuminated the keyboard as the final duet reached its emotional climax just to die away to a barely audible whisper. The poetic beauty and ravishing sounds that Giovanni created just illustrated his quite extraordinary poetic artistry.

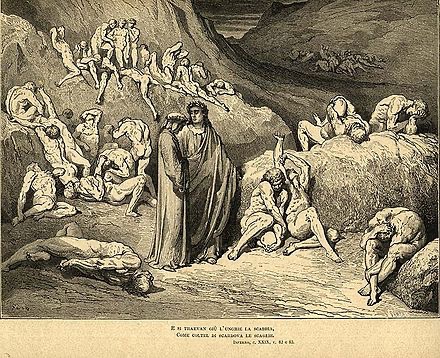

His complete identification with Liszt’s Dante Sonata was quite remarkable for the dramatic opening and the beauty of the central episode as it gradually reawakens and reveals a burning cauldron of sounds, where octaves and technical hurdles abound that Giovanni fearlessly took in his stride as he revealed the true musical shape of this might tone poem.

An ovation from a distinguished audience gathered in this remarkable space that has been bringing culture to Nicosia for the past twenty years.

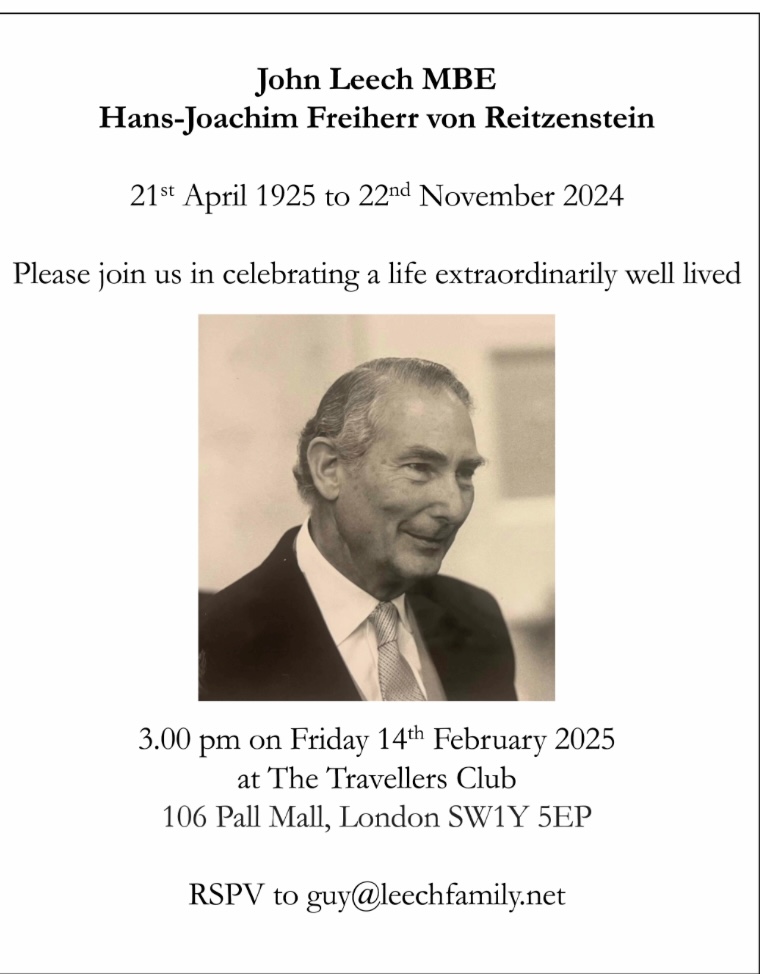

Three encores that included Cziffra ‘s magical transcription of Vecsey’s Valse Triste and Liszt’s 12th Hungarian Rhapsody, but it was the last piece of the evening that touched us even more. A disarming waltz by Puccini, his only original piano piece, that he was to use in La Boheme. Giovanni dedicated it to the memory of the founder of the Keyboard Trust ,John Leech, who had passed away in his hundredth year on S.Cecilia ‘s day – the patron saint of music! It was the piece that Giovanni had played on a Keyboard Trust tour in Germany the day before S. Cecilia day, and a live recording had been sent to our beloved founder as he was about to be called to a far more beautiful place than we could ever imagine.

Piano Sonata No. 21 in C major , Op. 53, known as the Waldstein, is one of the three most notable sonatas of his period middle (the other two being the Appassionata op 57 and Les Adieux op 81a . It was completed in summer 1804 and surpassing Beethoven’s previous piano sonatas in its scope, the Waldstein is a key early work of Beethoven’s “Heroic” decade (1803–1812) and set a standard for piano composition in the grand manner.

The sonata’s name derives from Beethoven’s dedication to his close friend and patron Count Ferdinand Ernst Gabriel von Waldstein , member of Bohemian noble Waldstein family. It is the only work that Beethoven dedicated to him. It is in three movements :

Allegro con brio

Introduzione: Adagio molto

Rondo . Allegretto moderato — Prestissimo

The Andante favori was written between 1803 and 1804, and published in 1805. It was originally intended to be the second of the three movements of Beethoven’s Waldstein op 53.The following extract from Thayer’s Beethoven biography explains the change:Ries reports (Notizen, p. 101) that a friend of Beethoven’s said to him that the sonata was too long, for which he was terribly taken to task by the composer. But after quiet reflection Beethoven was convinced of the correctness of the criticism. The andante… was therefore excluded and in its place supplied the interesting Introduction to the rondo which it now has. A year after the publication of the sonata, the andante also appeared separately.

It was composed as a musical declaration of love for Countess Josephine Brunsvik but the Brunsvik family increased the pressure to terminate the relationship. She could not contemplate marrying Beethoven, a commoner.The reason for the title was given by Beethoven’s pupil Czerny, quoted in Thayer: “Because of its popularity (for Beethoven played it frequently in society) he gave it the title Andante favori (“favored Andante”).

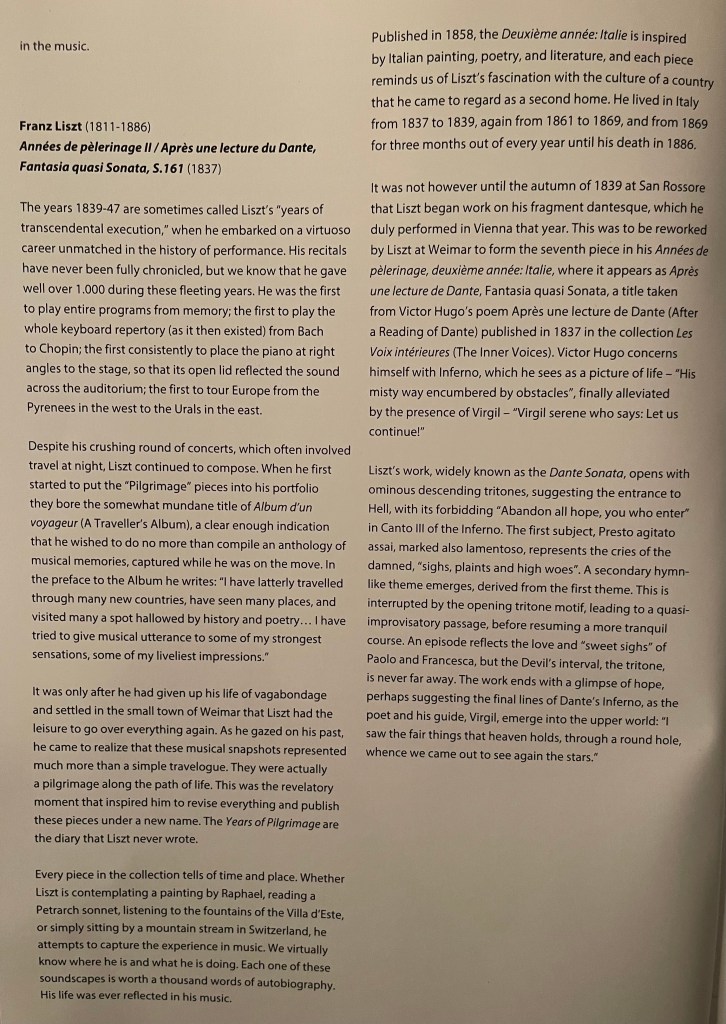

21 March 1685 Eisenach

28 July 1750 (aged 65) Leipzig

1 April 1866 – 27 July 1924

Alfred Brendel said of Busoni’s playing that it “signifies the victory of reflection over bravura” after the more flamboyant era of Liszt. He cites Busoni himself: “Music is so constituted that every context is a new context and should be treated as an ‘exception’. The solution of a problem, once found, cannot be reapplied to a different context. Our art is a theatre of surprise and invention, and of the seemingly unprepared. The spirit of music arises from the depths of our humanity and is returned to the high regions whence it has descended on mankind.” Busoni, born in Italy of an Italian father and a German mother, displayed a passion for Bach at an early age. A prodigy who played some of his own compositions in a piano recital in Vienna when he was 10 years old, Busoni made an exhaustive study of Bach’s music and throughout his adult life worked tirelessly at editing and making transcriptions of works by the Baroque master. His philosophical notions of music and the advanced practices of composition that he applied to his own pieces seem now to be at odds with such a bravura, flamboyant piece of work as his transcription for piano of the Chaconne from Bach’s Partita No. 2 for solo violin. The transcription was made sometime in the late 1890s and was dedicated to the pianist Eugene d’Albert; Busoni himself played it frequently on his own blazingly brilliant recitals.

Lest it be thought that Busoni was being irreverent in appropriating the lofty Chaconne for showpiece purposes, one must remember that the unimpeachably ethical Brahms made a piano transcription of the selfsame piece, for left hand alone. It must be said that, whereas Brahms imitates the original as closely as possible, Busoni ventures an arrangement that seems to be a piano realization of a grand orchestral or organ work rather than one for a single violin.

In fact, the Chaconne, the final movement of the Partita, is monumental in its original version—a set of more than 60 variations on a simple bass theme. The great Bach scholar Philipp Spitta (1841-1894) gave a description of the Chaconne that might have quickened Busoni’s fascination with it. Wrote Spitta:

“The overpowering wealth of forms displays not only the most perfect knowledge of the technique of the violin, but also the most absolute mastery over an imagination the life of which no composer was ever endowed with… What scenes the small instrument opens to our view!… From the grave majesty of the beginning to the 32nd notes which rush up and down like very demons; from the tremulous arpeggios that hang almost motionless, like veiling clouds above a gloomy ravine, till a strong wind drives them to the tree tops, which groan and toss as they whirl their leaves into the air; to the devotional beauty of the movement in D major, where the evening sun sets in the peaceful valley. The spirit of the master urges the instrument to incredible utterances; at the end of the major section, it sounds like an organ, and sometimes a whole band of violins seems to be playing. [Busoni took this reference seriously.] The Chaconne is a triumph of spirit over matter such as even Bach never repeated in a more brilliant manner.”Busoni’s transcriptions go beyond literal reproduction of the music for piano and often involve substantial recreation, although never straying from the original rhythmic outlines, melody notes and harmony. This is in line with Busoni’s own concept that the performing artist should be free to intuit and communicate his divination of the composer’s intentions. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://derricksblog.wordpress.com/2016/02/28/johann-sebastian-bach-and-bach-busoni-chaconne-in-d-minor-jascha-heifetz-violin-and-helene-grimaud-piano/&ved=2ahUKEwjgstfF6syLAxVuVqQEHR4iMZUQFnoECCkQAQ&usg=AOvVaw3k3IORkRtzNnpOa48knBMv

31 July 1886 (aged 74) Bayreuth , Kingdom of Bavaria, German Empire

Liszt generally approaches transcriptions one of two ways. The first is a relatively faithful transcription, taking songs and phrases from operas or symphonies and composing a reproduction of the music for the keyboard. In other transcriptions he is more improvisational, taking a work and building it in his own image.

In Liszt’s transcriptions and paraphrases of Verdi, we hear as much of Liszt as we do of the great Giuseppe. The composer makes sure the beautiful melodies are kept intact as much as possible, while still putting his own Lisztian spin on them. Liszt coined the terms “transcription ” and “paraphrase”, the former being a faithful reproduction of the source material and the latter a more free reinterpretation.He wrote substantial quantities of both over the course of his life, and they form a large proportion of his total output—up to half of his solo piano output from the 1830s and 1840s is transcription and paraphrase, and of his total output only approximately a third is completely original. In the mid-19th century, orchestral performances were much less common than they are today and were not available at all outside major cities; thus, Liszt’s transcriptions played a major role in popularising a wide array of music such as Beethoven’s symphonies . Liszt’s transcriptions of Italian opera, Schubert songs and Beethoven symphonies are also significant indicators of his artistic development, the opera allowing him to improvise in concert and the Schubert and Beethoven influence indicating his compositional development towards the Germanic tradition. He also transcribed his own orchestral and choral music for piano in an attempt to make it better known.

Verdi wrote his Egyptian opera Aida for the opening of the Cairo Opera House in 1871. Aida, daughter of the King of Ethiopia but enslaved by the Egyptians, is in love with Radames, appointed captain of the Egyptian armies in their fight against the Ethiopians. Victorious in battle, Radames is promised the hand of Aida’s mistress, Amneris, daughter of the King of Egypt, as a reward for his triumph. In an assignation with Aida, whom he loves, he divulges military secrets to her, overheard by her father, a prisoner of the Egyptians. Accused of treachery, Radames is condemned to death, to the dismay of Amneris, and, immured in a tomb, he is joined by Aida, allowing the two to die together, while Amneris mourns the fate of her beloved Radames. Liszt offers a paraphrase of the Danza sacra e duetto final,published in 1879. The sacred dance, from the end of the first act, accompanies the reception by Radames of the sacred sword, the symbol of his army command. Priestesses in the temple chant their prayer to the god Phtha, Possente, possente Phtha!, followed by their dance. In the fourth act the chant of the priestesses in the temple is heard, as Radames and Aida, entombed below, bid farewell to life in O terra addio, o valle di pianti (O earth, farewell, O vale of tears, farewell), and Amneris, distraught, offers her own prayer.

First staged in Rome in 1853, Il trovatore has a plot of some complexity. The troubadour of the title, Manrico, is the supposed son of the gypsy Azucena, but actually the stolen child of the old Count di Luna, a rebel and declared enemy of the young Count di Luna. Both are in love with Leonora, and Manrico, in his stronghold, is preparing to marry her, when news comes of the imminent death of his supposed mother, taken by the Count and condemned to death by burning. In his attempt to save her, Manrico is taken prisoner by the Count. In the fourth act Leonora, brought to a place outside Manrico’s prison, thinks to bring him new hope. From the tower the Miserere is heard, Miserere d’un’ alma già vicina / Alla partenza che non ha ritorno! (Have mercy on a soul already near / To the parting from which there is no return). Leonora’s horrified exclamation, Quel suon, quelle preci solenni, funeste (What sound, what solemn, mournful prayers) leads to Manrico’s Ah che la morte ognora / È tarda nel venir (Ah how slow the coming of death), from the tower, his farewell to his beloved. Once again Liszt has chosen the point of highest tragedy for his 1859 paraphrase. It is followed by Leonora’s offer of herself to the Count, in return for her lover’s release, having secretly taken poison, her death, and that of Manrico, executed, but now finally revealed by Azucena to the Count as his own brother.

Liszt’s concert paraphrases, are more than mere transcriptions, offering a re-interpretation based on thematic material drawn from their source. Among the best known of his Verdi arrangements is his Rigoletto Paraphrase de concert, written in 1859. Verdi’s opera had had its first performance in Venice in 1851. The plot centres on the court jester of the title, a servant and accomplice of the Duke of Mantua in his amorous adventures. Cursed by a courtier whose daughter the Duke has dishonoured, Rigoletto suffers the loss of his own daughter, Gilda, seduced by the Duke and then abducted, for the Duke’s pleasure, by the courtiers. In the last act of the opera Rigoletto has hired an assassin, Sparafucile to murder the Duke as he dallies with Sparafucile’s sister, Maddalena. They are observed from the darkness outside by Rigoletto and his daughter, who is to die at the assassin’s hands. It is this final scene that Liszt takes as the basis of his paraphrase. The theme that dominates is the Duke’s Bella figlia d’amore (Fair daughter of love), interspersed with the light-hearted replies of Maddalena, and the exclamations of Gilda, as she sees her lover’s infidelity exposed.

Après une lecture du Dante: Fantasia quasi Sonata also known as the Dante Sonata is a piano sonata in one movement, writen in 1849. It was first published in 1856 as part of the second volume of his Années de pèlerinage (Years of Pilgrimage) and was inspired by the reading of Victor Hugo’s poem “Après une lecture de Dante” (1836).The Dante Sonata was originally a small piece entitled Fragment after Dante, consisting of two thematically related movements , which Liszt composed in the late 1830s.He gave the first public performance in Vienna in November 1839. When he settled in Weimar in 1849, he revised the work along with others in the volume, and gave it its present title derived from Victor Hugo’s own work of the same name and was published in 1858.

Masterclasses in Cyprus

Giovanni Bertolazzi working with Maria Matheus ( Chopin Fantasie Impromptu) Ella Zhou ( Chopin 2nd Ballade ) Anna Avramidou ( a student of Tessa Nicholson at the Purcell School playing Beethoven op 57 Ist Movement and Debussy Feux d’Artifice). Two local pianists playing Chopin with passion and intelligence.

A Fantasie Impromptu all too rarely heard in the concert hall these days was played with loving care and beauty and just needs sorting out technical details before taking flight .

A second Ballade played with remarkable control and technical brilliance for an 18 year old schoolgirl. A search for more beauty and delicacy of phrasing will turn this into a remarkable performance.

An Appassionata played with mastery and total respect for the score. Quite considerable technical mastery too but above all a musical intelligence and dynamic drive. Debussy was played with a clarity and precision that was quite remarkable for a 17 year old student on a short return home for half term from the Purcell School in the UK

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2024/12/25/point-and-counterpoint-2024-a-personal-view-by-christopher-axworthy/