MOZART: Adagio in B minor, K540

MOZART: 12 Variations on ‘Ah vous dirai-je, Maman’

MOZART: Sonata No. 11 in A major, K. 331

I. Andante grazioso

II. Menuetto

III. Alla turca – Allegretto

Intermission

SCHUBERT: Fantasia in F minor, D.940

arr. Grinberg for solo piano

GRIEG / GINZBURG: Peer Gynt Suite

“In the Hall of the Mountain King”.

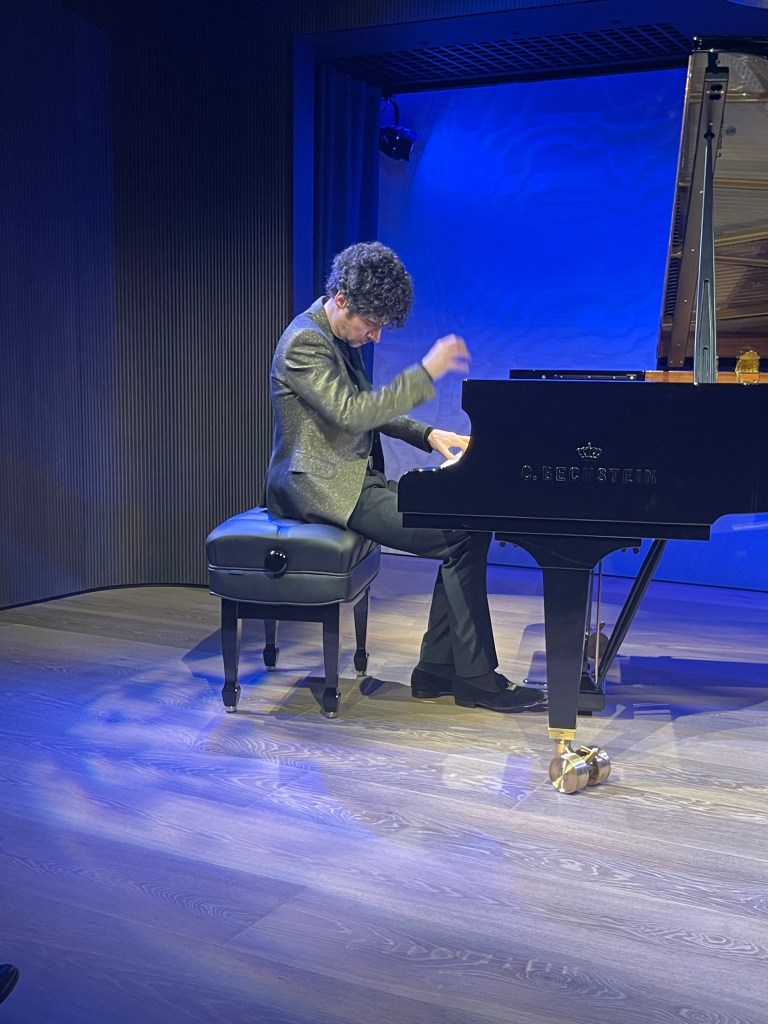

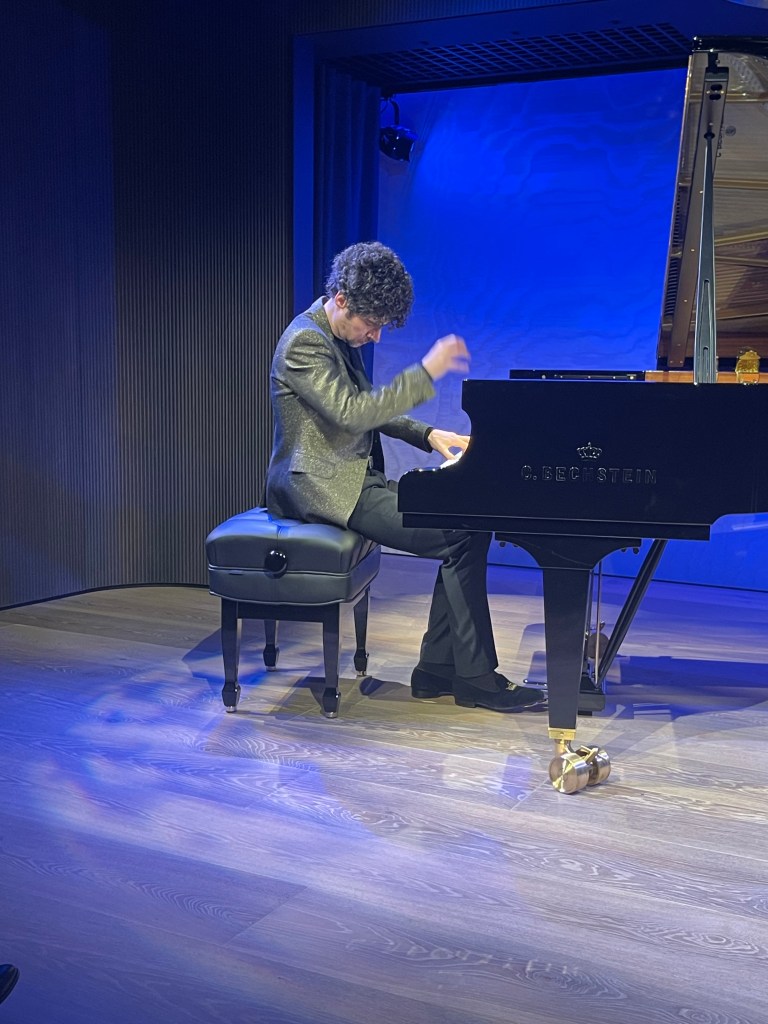

Thomas Masciaga opened the Bechstein Young Artists Series with canons covered in flowers

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2025/02/02/thomas-masciaga-opens-the-bechstein-young-artists-series-with-canons-covered-in-flowers/

Evening concerts starting from 18 pounds and a sumptuous restaurant that is also opening for luncheon.

A beautiful new hall that is just complimenting the magnificence of the Wigmore Hall and the sumptuous salon of Bob Boas.Providing a much needed space for the enormous amount of talent that London,the undisputed capital of classical music,must surely try to accommodate

The new Bechstein Hall comes of age as the suave elegance and mastery of the Leeds Gold Medal winner of 2012 ,Federico Colli, conquers a full hall greeting his extraordinary playing with an ovation usually only reserved for the stadium .

It is a unique blend of modern and old style playing that holds one’s attention with whatever he does, as the music speaks with the beauty and expression of the human voice.

To see him gently allow his hand to glide silently over the keyboard before letting his fingers caress the keys with Matthayan sensitivity, as the first notes of one of the great masterpieces for keyboard was allowed to take wing .

I have only seen the like from Rosalyn Tureck who would insist the piano lid was shut before she came on stage so as not to allow even a speck of dust to lie on the keys that might upset her quite unique sense of touch.

Federico’s sense of colour and delicacy allowed Mozart’s B minor Adagio to share its whispered profundity with an audience that were immediately mesmerised by notes that were more operatic than instrumental.

Gently ornamenting Mozart’s bare outline with infinite grace and style but at the recapitulation allowing Mozart’s simple notes to speak for themselves with quite heartrending effect. This was a musician, much in the Russian tradition, as Horowitz was to show us, where every note has a vibrant sound and a life of its own like the human voice. It was Horowitz who astonished and even shocked a whole generation when he performed Mozart and Scarlatti with more respect for the music than dry tradition .

Always with intelligence and not a little scholarship allowing notes born for instruments with limited possibility of expression the ability to ring free on the modern day piano with the inflections of the human voice, that together with the dance was, and is, the inspiration for all composers.

Federico has been trained in the Russian tradition at the International Piano Academy in Imola with Boris Petrushansky. A master pianist himself but one who with generosity, humility and sense of freedom has guided so many musicians who have passed through his class over the past three decades. This, of course, accounted for the transcriptions of Schubert and Grieg by Russian pianist composers.

Transcriptions more to highlight pianistic mastery than reveal hidden secrets of masterpieces. Schubert’s Fantasie ,whilst the opening theme was played with breathtaking beauty and sensitivity. A sense of balance that with two instead of four hands could allow Schubert’s sublime melodic outpouring to shine as never before. But later the added chords and pianistic tricks turned a masterpiece into something it was never born to be. Like Busoni’s ending of the Goldberg Variations with the triumph of a showman rather than the poetic whispers of a genius . Grinberg too turns Schubert’s sublime poetic world into a triumphant shout from the rooftops . These works like a lot of Busoni or Stokowski transcriptions were born to bring unknown masterworks into the concert platform long before recordings or live performances were readily available. It was interesting to hear these rather dated transcriptions that like old photographs are turning a little brown at the edges. Performances of ‘Schubert’ and ‘Grieg’ in which Federico’s mastery shone through, not just digital but also of colour and insinuating sounds, created by a magician who understood the meaning of balance and the importance of the pedals, like the masters of the Golden Era of piano playing at the start of the 20th century.

A collage of Grieg under the title ‘In the Hall of the Mountain King’, because after the sublime pastoral opening and the quixotic dance of true jeux perlé playing of yester year, the climax and whole point of the exercise was the burning intensity and exhilarating excitement that could be generated by playing of enormous power and velocity as was to be found in the Hall ! The final triumphant chords were greeted by an audience who had been involved with the same fever pitch participation as at the World Cup.

But it was the encore of a simple Scarlatti Sonata that showed off the true artistry of this remarkable artist .A crystalline clarity and sense of style, with trills that unwound like tightly wound springs with a buoyancy and charm that was irresistible.

It had been the same simple mastery that we had experienced in the first half of this recital with the Variations by Mozart on ‘Ah vous direi -je Maman’ and the Sonata ‘Alla Turca’ K 331. The Variations entered immediately after the Adagio in B minor where maybe the audience were frightened to clap after such intimate profound musings. But it worked wonderfully well to hear this nursery rhyme theme played with such charm and beguiling simplicity.The variations too unfolded with a sense of timing and charm that often brought a smile of childhood recollection.There was also a scintillating ‘fingerfertigkeit’ of quite remarkable clarity and precision and a dynamic drive at the end like a hurricane of ‘joie de vivre’. Federico’s remarkable sensitivity and artistry were so intense it was hard to concentrate for an entire first half, as well as he obviously could .And maybe this intensity and continual change of colour and dynamics should have been rationed more wisely for us mere mortals.

A mellifluous beauty to the opening theme and variations of the Sonata in A was followed by an imperious minuet and beautifully contrasted trio. But it was the simplicity and dynamic drive of the Rondo all Turca that woke us up out of our dreamy soporific state. Ornaments that were played in an unusual way but I am sure that the musician Federico had researched this with intelligence and dedication. There was even an improvised cadenza before the final triumphant ride to glory which was breathtaking in its dynamic drive and energy .

Federico Colli at Duszniki Festival-Ravishing beauty,showmanship and authority of a great artist

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2023/08/06/federico-colli-at-duszniki-festival-ravishing-beautyshowmanship-and-authority-of-a-great-artist/

Federico Colli in Poland

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2020/08/11/federico-colli-in-poland/

Praised by The Daily Telegraph for “his beautifully light touch and lyrical grace” and labelled “one of the more original thinkers of his generation” by Gramophone, Federico Colli has been rapidly gaining worldwide recognition for his compelling, unconventional interpretations and clarity of sound. The remarkable originality and highly imaginative, philosophical approach to music-making has distinguished Federico’s performances and recordings as miraculous and multidimensional.

Federico’s first release of Sonatas by Domenico Scarlatti, recorded on Chandos Records for whom he is an exclusive recording artist, was awarded “Recording of the Year” by Presto Classical. The second volume of Scarlatti’s Sonatas was named “Recording of the Month” by both BBC Music Magazine and International Piano Magazine, and it has been chosen by BBC Music Magazine as “one of the best classical albums released in 2020″.

Following his many early successes, one being the Gold Medal at the 2012 Leeds International Piano Competition, the International Piano magazine selected him as “one of the 30 pianists under 30 who are likely to dominate the world stage in years to come”. More recent successes include being selected for Fortune Italia’s ’40 under 40’ list of most influential people in Arts and Culture.

Federico has performed with renowned orchestras including the Mariinsky Orchestra and St Petersburg Philharmonic, Philharmonia Orchestra, Royal Philharmonic, BBC Symphony and BBC Philharmonic, Royal Liverpool Philharmonic, Euskadiko Orkestra, Royal Stockholm Philharmonic, Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, RAI Symphony Orchestra and Orchestre National d’Île-de-France.

He has also worked with esteemed conductors including Valery Gergiev, Vladimir Ashkenazy, Yuri Temirkanov, Juraj Valčuha, Ion Marin, Thomas Søndergård, Ed Spanjaard, Vasily Petrenko, Sir Mark Elder, Dennis Russel Davies and Sakari Oramo.

Federico enjoys a busy chamber music schedule, working with artists including Josef Špaček, Francesca Dego,Timothy Ridout and Laura van der Heijden.

In July 2024, he made a successful play-direct debut with the Academy of St Martin in the Fields, which was followed by a return to Helsingborg Piano Festival, where Federico play-directed the Helsingborg Symphony Orchestra in the Festival’s opening concert.

One of the most prolific and intriguing recitalists, Federico showcased his mastery in some of the world’s most famous halls, such as Vienna Musikverein and Konzerthaus, Berlin Konzerthaus, Munich Herkulessaal, Leipzig Gewandhaus, Amsterdam Royal Concertgebouw, London Royal Albert Hall and Royal Festival Hall, Prague Rudolfinum, Paris Philharmonie, Rome Auditorium Parco della Musica, Tokyo Nikkei Hall, Hong Kong City Hall, Seoul Kumho Art Hall, New York Lincoln Centre and Chicago Bennet Gordon Hall.

He has appeared in festivals such as Klavier Festival Ruhr in Dortmund, Dvorak International Festival in Prague, Chopin and his Europe International Festival in Warsaw, Lucerne Festival and Ravinia Festival in Chicago.

In 24/25 season, Federico is Artist-in-Residence with the Janáček Philharmonic Ostrava in Czech Republic. Throughout the season he will perform Rachmaninov Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini with conductor Tomáš Netopil and the Janáček Philharmonic Ostrava, in addition to a solo recital and a chamber music concert with the musicians from the orchestra. In the same season, he will twice perform with Orchestre National d’Île-de-France at the Philharmonie de Paris (Rachmaninov Piano Concerto no 3 and a chamber music programme), tour the UK with Nürnberger Symphoniker (Beethoven Piano Concerto no. 5 and Grieg Piano Concerto), debuts with the Warsaw Philharmonic (Grieg Piano Concerto), and the ‘George Enescu’ Philharmonic in Bucharest (Shostakovich Piano Concerto no. 1). In recitals, Federico will return to Prague Rudolfinum, play twice at the Bechstein Hall in London, return to Brescia Bergamo Piano Festival, and perform in Ravenna and Rovereto (Italy), Chiasso (Switzerland) and Vilagarcia (Spain). In February 2025, Federico will collaborate with the Calidore String Quartet in concerts at the Warsaw Philharmonic and Louisiana Museum of Modern Arts in Denmark.

In addition to live performances, Federico maintains a busy recording schedule and records exclusively for Chandos Records. To demonstrate his love for Mozart, during the pandemic Federico created an educational series of short videos for his YouTube channel, designed to re-discover Mozart’s Fantasy in C minor K475 and place Mozart’s musical ideas in a historical and cultural context. Inspired by the mystery surrounding the genesis of the piece, Federico created an invigorating story based on his deep-dive research into Mozart’s biographies, letters and XVIII century history and culture. First in a series of Mozart albums is a disc featuring works for solo piano released in May 2022, followed by Mozart’s Piano Quartets released in August 2023 and gathered highly positive reviews. The Times wrote: “His [Colli’s] crisp, inquisitive phrasing is promptly displayed in the more turbulent of the two quartets (K478 in G minor). Without being mannered he grabs your attention, while leaving plenty of space, as Mozart does, for the other performers to spread delight.” Federico’s future recording plans for Chandos include a Russian project focused on Shostakovich.

Born in Brescia in 1988, he has been studying at the Milan Conservatory, Imola International Piano Academy and Salzburg Mozarteum, under the guidance of Sergio Marengoni, Konstantin Bogino, Boris Petrushansky and Pavel Gililov.

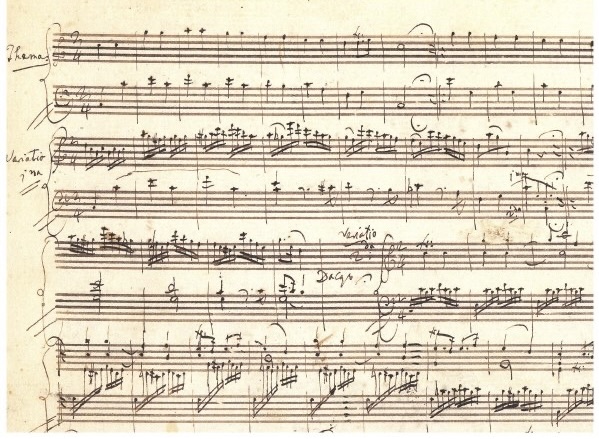

Twelve Variations on “Ah vous dirai-je, Maman” K 265/300e, was composed when Mozart was around 25 years old (1781 or 1782). There are twelve variations on the French folk song “Ah! vous dirai-je,maman “. The French melody first appeared in 1761, and has been used for many children’s songs, such as “Twinkle,Twinkle,Little Star”,”Baa,Baa,Black Sheep”, and the “Alphabet Song.” For a time, it was thought that these variations were composed in 1778, while Mozart stayed in Paris from April to September in that year, the assumption being that the melody of a French song could only have been picked up by Mozart while residing in France. For this presumed composition date, the composition was renumbered from K. 265 to K. 300e .

Later analysis of Mozart’s manuscript of the composition indicated 1781/1782 as the probable composition date.They were first published in Vienna in 1785.Only very few piano works have become as popular as this theme with twelve variations. It already caught on soon after Mozart’s death, as witnessed by the numerous handwritten copies and prints. Although nothing is known with any certainty regarding its genesis, we can now conclusively date “Ah, vous dirai-je Maman” to 1781. At that time Mozart wanted to make his way as a prominent piano teacher in Vienna.

The Adagio in B minor K. 540, Mozart added it into his Verzeichnis aller meiner Werke (Catalogue of all my Works) on 19 March 1788.

At 57 bars , the length of the piece is largely based on the performer’s interpretation, including the decision of whether to do both repeats; it may last between 6 and 16 minutes. The key of B minor is very rare in Mozart’s compositions and is used in only one other instrumental work, the slow movement from the Flute Quartet n. 1 in D , K. 285. Mozart specifically noted the key of B minor in his catalogue, which he did for no other piece.Mozart composed his Adagio in B minor K. 540 at a time when his financial situation was steadily deteriorating. The war against the Turks was constraining the Viennese people’s interest in music – works were not commissioned and concerts did not take place. It was of no matter that Mozart had shortly before (in 1787) been appointed a salaried k.k. Kammer-Kompositeur. Nevertheless in this year he composed several of his most important works: the “Coronation Concerto” K. 537, the three late symphonies as well as several piano trios. And he also composed this extraordinarily poignant Adagio in B minor .

The Piano Sonata No. 11 in A major, K . 331 , was published by Artaria in 1784, alongside K. 330 and K. 332 The third movement the “Rondo alla Turca“, or “Turkish March“, is often heard on its own and regarded as one of Mozart’s best-known piano pieces.The opening movement is a theme and variation , Mozart defied the convention of beginning a sonata with an allegro movement in sonata form. The theme is a siciliana , consisting of an 8-measure section and a 10-measure section, each repeated, a structure shared by each variation. In autumn 2014 a hitherto unknown Mozart autograph of the famous Piano Sonata in A major (with the enduring “Turkish March”) surfaced in Budapest. After a painstaking study of the manuscript and a meticulous comparison with all of the other sources it emerged that there are serious deviations from the musical text as we know it. The Hungarian librarian Balázs Mikusi discovered in Budapest’s National Széchényi Library four pages from the first and middle movements in Mozart’s autograph manuscript of the sonata. Until then, only the last page of the last movement, which is preserved in the International Mozarteum Foundation , had been known to have survived. The paper and handwriting of the four pages matched that of the final page of the score, held in Salzburg. The original score is close to the first edition, published in 1784. In the first movement, however, in bars 5 and 6 of the fifth variation, the rhythm of the last three notes was altered. In the menuetto, the last quarter beat of bar 3 is a C♯ in most editions, but in the original autograph an A is printed. In the first edition, an A is also printed in bar 3, as in the original, but on the other hand a C♯ is printed in the parallel passage at bar 33, mirroring subsequent editions. On 26 September 2014 Zoltán Kocsis gave the first performance of the rediscovered score, at the National Library in Budapest. Federico has studied these scores and many of the differences are incorporated into his performance not least the unusual ornamentation of the Turkish March.

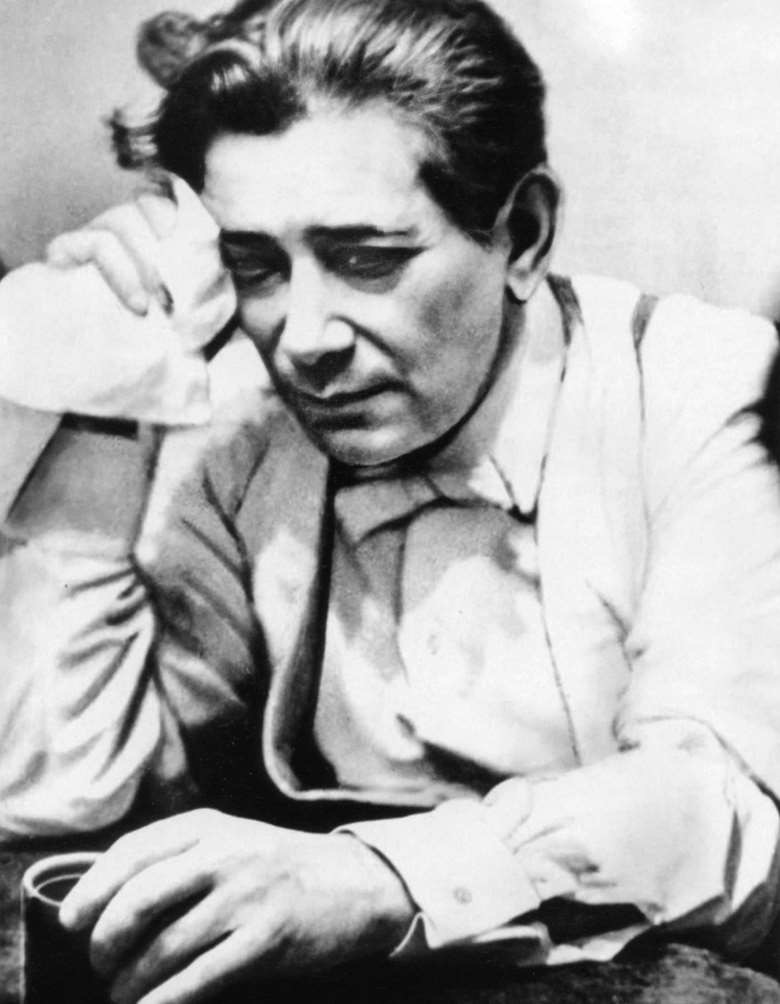

At the age of 50, after Stalin died, she was finally allowed to travel abroad. In all, Grinberg went on 14 performing tours – 12 times in the Soviet bloc countries and twice in the Netherlands where she became a nationally acclaimed figure. Critics compared her performances with those of Horowitz,Rubinstein and Haskil.

Only at the age of 55, was she granted her first – and last – honorary title of Distinguished Artist of the Russian Soviet Federation. At 61, she was given a professorship at the Gnessin Institute of Music , where she had a close friendship with pianist Maria Yudina, who said Grinberg was the “one person she wanted to play at her funeral”. Maria Grinberg died on July 14, 1978, in Tallinn ,Estonia, ten weeks before her seventieth birthday. The Gnessin Institute’s director, chorus master Vladimir Minin (who a year before had forced Grinberg to resign from her teaching position), refused to hold a memorial ceremony on the Institute’s premises, and it was only thanks to the efforts of Deputy Minister of Culture Kukharsky, the great pianist was given her last honour in a proper way.

Her sense of humour was legendary. Those who knew her recall a story. Her patronymic was Israilyevna (that is, “daughter of Israel”, Israel being the first name of her father). In 1967, during the period of heightened tension between the Soviet Union and the State of Israel which the Soviets always addressed as “Israeli aggressors,” Grinberg introduced herself as “Maria Aggressorovna.”

He often made the front page of newspapers and was compared not unfavourably to Cortot, Hofmann and Rachmaninov

It was during these years that Ginzburg built up his legendary piano technique. Although Anna Goldenweiser was his main teacher, her illustrious husband also worked with the boy. ‘He gave me fantastic technical preparation. I played all kinds of scales with different accents and rhythmic patterns. I really knew all 60 Hanon exercises in all keys and I could play each one perfectly,’ Ginzburg later said of his studies with Goldenweiser.

In 1916 Ginzburg formally entered the Moscow Conservatory. As he recalled, ‘they considered me a prodigy, especially in technique’. His work with Goldenweiser continued: ‘I played Czerny’s Op 299 [The School of Velocity] and Op 740 [The Art of Finger Dexterity] … Absolute accuracy was required. Goldenweiser could come in the room at any time and check. He was very thorough with me and generous with his time. Sometimes it was very difficult. One time he got mad and threw all my notebooks out the window from the fifth floor and I had to run and get them.’

In 1924 Ginzburg graduated from the Moscow Conservatory with a gold medal. In the Conservatory he had been a star, always praised, but after graduating things didn’t come easily to him. For the first time in his life his playing was criticised, and as he had no management he found it difficult to get concert engagements. Ginzburg began to feel dissatisfied with his playing and technique, and finally decided that a full re-evaluation was in order. Although this was a difficult realisation for the young pianist, he later stated that had this not happened he never would have developed into the pianist he became.

A turning point in Ginzburg’s career occurred in 1927. He was selected to compete in the First International Chopin Piano Competition in Warsaw, where he won fourth prize (his countryman Lev Oborin took first). Following that success, his career took off. A wildly successful tour of Poland quickly followed. More and more engagements came, including an invitation to tour America, and critics were universally enthusiastic about the playing of this young virtuoso. Interestingly, in the midst of all this, he received a letter from Anna Goldenweiser in which she expressed fear that this success might change him for the worse. ‘Never feel that the quality of your performance is measured by external success, which is so capricious … Please don’t misunderstand me, I know more than anyone what you are worth … No matter what they say and no matter how they shout, you yourself should know better than anyone what the truth is.’ Ginzburg took this advice to heart and decided to return to Russia. He turned down numerous engagements, including the USA tour, so that he could finish his studies, continue to improve his playing and learn more repertoire.

Despite adding works by Brahms, Schumann, Ravel and Scriabin (all of the Op 8 Études) to his repertoire, as well as various transcriptions, Ginzburg continued to be associated most of all with the music of Chopin and Liszt. Critics singled out his exceptional virtuosity, finding him an ideal interpreter of Liszt. In the 1930s he further expanded his repertoire with works by Beethoven, Mozart and, surprisingly, Kabalevsky, a contemporary composer whose music he particularly enjoyed. In 1936 he toured Sweden, the Baltic countries and Poland again. His success was overwhelming everywhere he played. He often made the front page of newspapers and was compared not unfavourably to Cortot, Hofmann and Rachmaninov, who were also touring Poland at that same time. However, the demands of such an intense touring schedule took their toll. ‘During 12 days [in Poland] I played 10 concerts,’ he recalled. ‘I hardly slept a single night because I was travelling all the time.’ Despite the exuberant reviews and ecstatic public reception, Ginzburg again began to have self-doubts. There was never time to develop his artistry and he became more and more dissatisfied with his playing. Adding to his workload, he had accepted a position at the Moscow Conservatory in 1932, and he was frequently invited to sit on piano competition juries.

Ginzburg’s Chopin is highly refined and elegant with tasteful but expressive rubato

Over the next five years, Ginzburg maintained a busy schedule, but also worked on his art. It was the beginning of a transformation in his playing towards a more mature style that penetrated deeper into the music’s meaning. Works by Beethoven started to feature more often in Ginzburg’s programmes: whereas in 1936 he played a series of concerts devoted to Liszt’s music, on 14 May 1940 he played an all-Beethoven programme for the first time. In the past, with few exceptions, he had avoided playing chamber music, but he began to add this increasingly to his activities. Such a transformation was difficult for the critics to grasp, as virtuosos are typically typecast as not being deeply penetrating musicians or sensitive collaborators. This was an issue that plagued him for the rest of his life, and even today he is often described as a virtuoso who excelled in Liszt rather than the well-rounded, fine musician he actually was. As one critic wrote, with a note of surprise: ‘Ginzburg is a brilliant virtuoso. But at the same time, he is also a subtle chamber musician.’

Any hopes Ginzburg had of touring outside of the Soviet Union were dashed by the outbreak of the Second World War. During the war Ginzburg was kept extremely busy. He taught not only his own students but also those of Lev Oborin when the latter was on tour. Ginzburg’s own concert tours within Russia continued, and he also played numerous times for soldiers and for the radio. ‘Today I play at 2, 6, and 9pm on the radio … I am very tired … the radio always orders new things and I never refuse anything.’ When the war ended, Ginzburg’s activities ramped up even further with over 100 concerts a year and frequent trips to the recording studio. He also got more interested in Russian repertoire and added many works by Tchaikovsky, Arensky, Anton Rubinstein, Scriabin, Borodin, Balakirev, Glinka and Medtner to his repertoire. In the late 1940s Ginzburg became increasingly interested in the music of Mozart. ‘When I was younger I loved the Romantics and was scared of the Classics. When I was older it was the reverse … When I play Mozart I feel every note. I breathe this music. There is a real creative joy when you feel you have discovered the composer’s hidden treasures.’ The one composer conspicuously missing from his programmes (not just then but throughout his career) was Rachmaninov. His reason for this was simple. He idolised Rachmaninov but could not imagine playing this music better than the composer himself – although it should be noted that he did play Rachmaninov’s Suites for two pianos several times during his career.

Ginzburg was never in favour with the ruling Communists, but in 1956 the regime finally allowed him to leave the Soviet Union to perform in Hungary. After huge success there, he was allowed to tour Czechoslovakia in 1959. His concerts were received so enthusiastically that further foreign tours and engagements were planned. There was great optimism for the future, but health issues tragically interfered with those plans. In May 1960 he suffered a heart attack and spent two months in hospital. After regaining his strength he resumed playing concerts, and was able to tour Yugoslavia in early 1961. Those concerts were also a resounding success, but Ginzburg’s health was in serious decline. He had been diagnosed with an untreatable cancer, and by August 1961 it became clear that the end was near. On 10 November 1961 Goldenweiser, who was also very ill at the time, sent him a deeply touching letter: ‘Dear Grisha … I love you so much that I fell ill together with you … Unfortunately your illness seems more serious than mine … Get well soon! I think about you all the time. I love you very much like a dear son. Your old (very old) A Goldenweiser.’ On 26 November Goldenweiser died. His student, Grigory Ginzburg, followed nine days later, on 5 December 1961.

Ginzburg’s death was a huge loss to the music world, but his legacy lives on through his brilliant transcriptions, his many students and his wonderful recordings. From his earliest days of concert-giving, Ginzburg often included transcriptions by Liszt, Busoni, Godowsky and others in his programmes. His virtuoso renditions would drive his audience into a frenzy. This fascination with transcriptions led to his creating his own. The most famous of these is of Figaro’s cavatina from Rossini’s Il barbiere di Siviglia, which is still played today by a few pianists. He also transcribed Grieg’s Peer Gynt Suite, Kreisler’s Praeludium and Allegro (in the style of Pugnani), Róz˙ycki’s Casanova waltz and Rakov’s Russian Song. The sheet music for all of these is available in a beautiful edition from the Jurgenson publishing house in Moscow.

As a professor for nearly three decades at the Moscow Conservatory, Ginzburg taught many students who went on to have successful careers. The pianist Gleb Axelrod is widely considered to be his greatest student. Although Axelrod is barely known in the West, he taught for many years at the Moscow Conservatory, and his recordings for Melodiya show him to have been a formidable pianist. Another student, Sergei Dorensky, became a legendary teacher in his own right, whose students include Nikolai Lugansky, Denis Matsuev and Olga Kern. Sulamita Aronovsky, another Ginzburg pupil, was for years one of the most sought-after piano teachers in England.

We are fortunate that Ginzburg left several hours of recordings for posterity. His recordings are consistently of a very high level, which is in no small part due to the fact that he enjoyed the process of making them. His recordings of Liszt’s Norma and Don Juanopera paraphrases, the Mozart/Liszt/Busoni Figaro Fantasy and the Tchaikovsky/Pabst Polonaise from Eugene Onegin are legendary. Although the virtuosic ease of the playing is what initially leaves one awestruck, the overall musicianship and ability to let the works unfold are equally impressive. He also made excellent recordings of various transcriptions by Godowsky, Galston and Tausig, his own Rossini transcription, several Schubert/Liszt songs and four of Liszt’s Paganini Études. These acclaimed recordings have always been a double-edged sword, since as fine as they were they have overshadowed his accomplishments in other areas of more ‘serious’ repertoire. For example, his recordings of Mozart’s A minor Piano Sonata, K310, and C major Piano Concerto, K503, rank among the finest recorded versions of these works yet they are nowhere near as well-known.