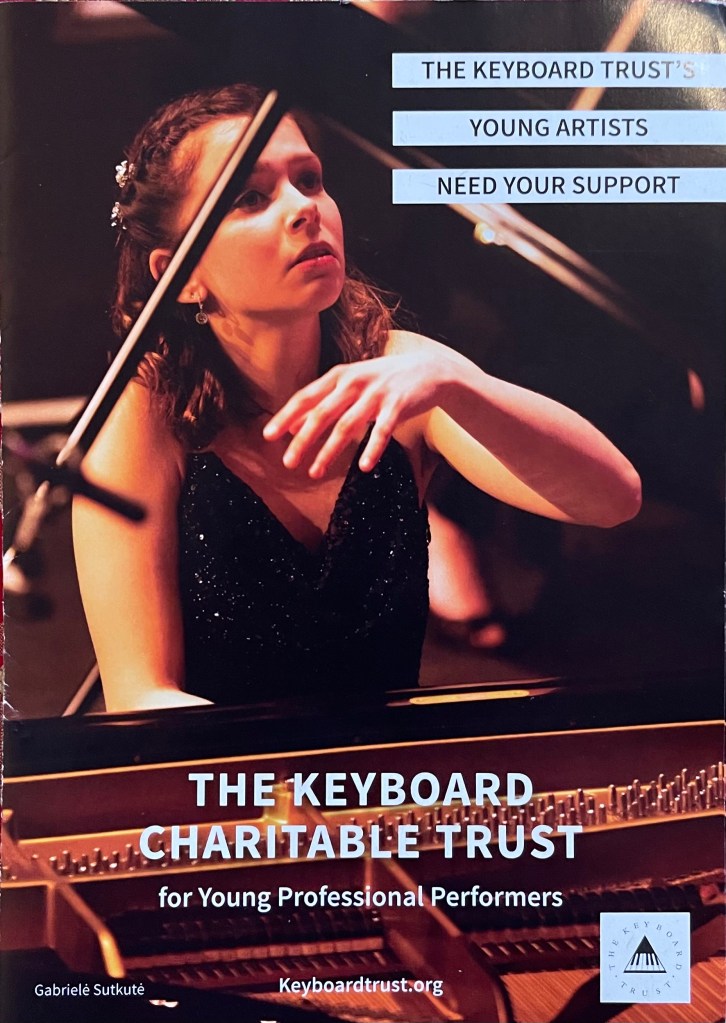

Gabrielé Sutkuté at the Lansdowne Club for her second recital for Bluthner Concerts. Following on from her superb recital eighteen months ago she was invited to fill this magnificent hall again with her supreme artistry

Gabrielé Sutkuté takes Mayfair by Storm ‘passion and power with impeccable style’

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2023/09/13/gabriele-sutkute-takes-mayfair-by-storm-passion-and-power-with-impeccable-style.

Playing of astonishing energy and dynamic drive but also charm and ravishing delicacy in this short showcase recital. A programme that ranged from the trifles of a youthful Beethoven, through the sumptuous rich orchestral sounds of Brahms, the refined simplicity of Rameau but above all the astonishing brilliance of Liszt.

An extraordinary display of transcendental piano playing but above all of a musicianship that could give such differing character to all she did.

There was charm and humour from the very first notes of Beethoven’s seven bagatelles op. 33 which opened the programme. She was living and relishing each note, whether it be a slight twitch of her nose or a glance of recognition, that were just part of the extraordinary vibrant sounds that she was producing at the keyboard. It was Brendel who was sometimes criticised for affectations such as these, but as he said I do not grunt or groan like Glenn Gould but just make grimaces . He tried unsuccessfully to cure himself with a mirror placed strategically in his practice studio, alas to no avail because his love and self recognition with the music were far too strong for such personal trivia ! The second Bagatelle marked ‘Scherzo’ was played with dynamic contrasts and a driving intensity as Beethoven’s spirited humour burst into effervescence. This was followed by the beautiful Schubertian outpouring of radiance and sunshine as one could see and hear what fun she was having. A simple ‘ländler’ followed, interrupted by contrasting brooding harmonic progressions before the return of the opening disarming earthly simplicity. Cascades of notes of the fifth were played with teasing brilliance with a passing cloud and dark change of character for the central episode. It was with simple grace and charm that the sixth was allowed to unfold before the frenzy and hysterical impatience of the final seventh. Long held pedals allowed streams of misty harmonies to interrupt this hurricane of Beethoven at his most impatient – A rage indeed – but with spirited good humour and simply a masterly storm in a teacup!

The two Brahms rhapsodies that followed were played with orchestral sounds of grandeur and potency. Gabrielé’s instinctive driving passion and energy allowed the two overpowering masterworks to ravish and seduce. Such rich sonorities from this very fine Blüthner piano and it was on the vibrations of such intensity that a radiant star was allowed to appear pianissimo with glowing beauty. Dynamic dramatic scales were played with electric energy as Gabrielé landed on the bass chords with terrifying power. There was also the disarming simplicity of the central ‘ländler’ that was allowed to unfold under the gentle sound of a distant bagpipe. There was magic in the air as Gabrielé allowed the music to rest exhausted and contemplate with golden whispered sounds the story that had been told.

The second rhapsody was bathed in pedal with its ponderous march allowed to wend its way forward with timeless insistence .It was the juxtaposition of these two elements that ignited with romantic colours a sumptuous world of orchestral sounds and majesty.

Four pieces from Rameau’s suite in D showed off a world of refined elegance and simplicity with ornaments that were like well oiled springs just adding a sparkling colour to this more formal world of elegance and style. Ravishing beguiling beauty of ‘Les Tendres Plaintes’ was followed by the crystal clear articulation and the dynamic contrasts of its time of ‘La Joyeuse’. The simplicity of ‘La Follette’ was followed by the rhythmic energy and teasing enticement of ‘Les Cyclopes’. Showing another side of the technical and stylistic perfection of Gabrielé which was like a breath of fresh air inbetween the boiling cauldron of Brahms and Liszt.

And it was Liszt that concluded this short but substantial ‘Concerto aperitivo’. Gabrielé bursting on to the scene like in all Rossini’s great operatic works with the great baritone aria from Otello. Drama and arresting rhythms immediately caught our attention as the great aria is allowed to pour from the very soul of the piano with Gabrielé’s total conviction and passionate adhesion. Waves of glorious sounds just enhance the opening of the curtain on such a rhetorical outpouring. The Tarantella entering on the final breath with stealth and cunning. Astonishing pianistic pyrotechnics played by this super charged young Lithuanian artist with clarity precision and overwhelming dynamic drive. To contrast was the ravishing beauty of the Neapolitan song that sings its heart out with unashamed abandon and seductive innuendo. Gabrielé played it with the ravishment and seduction it merits having a well earned rest bathed in the Neapolitan sun. That was before the kiss of the ‘Tarantella’ that ignited a bombshell in this delicate looking young artist who suddenly showed us how appearances can be deceptive.You have been warned!

After such a bombshell she needed much persuasion before finally relenting and offering us the civilised refined beauty of the Minuet and Trio of Haydn’s B minor Sonata n. 47 Hob XVI 32.

Now headed for Kaunas where she will perform the Grieg Piano Concerto with the State Symphony Orchestra at the weekend. A hall she tells me that is already sold out. It does not surprise me in the slightest knowing the growing reputation of this young Lithuanian artist.

Gabrielé Sutkuté plays Grieg with the YMSO under James Blair at Cadogan Hall

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2023/03/22/gabriele-sutkute-plays-grieg-with-the-ymso-under-james-blair-at-cadogan-hall/

Gabrielé Sutkuté at Leighton House ‘a star is born’

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2023/11/15/25295/

The Bagatelles reflect Beethoven’s diverse compositional cosmos in miniature and span almost his entire oeuvre from 1801/02 to 1824/25. In terms of playing technique, they range from moderate dexterity to demanding virtuosity.

In addition to the well-known collections Opp.33, 119 and 126, ten more pieces were found after Beethoven’s death in an envelope labelled “Bagatelles”. These included the revised version of “Für Elise” as well as two further revisions of bagatelles which appear here in print for the first time. For a long time it was assumed that Beethoven reworked seven older pieces for his op. 33, published in 1803. But in the meantime it has been determined that all the surviving sketches came into being in 1801/02, and that the autograph dates from 1802. The fact that the composer wrote such bagatelles for amateurs in temporal proximity to the demanding Piano Sonatas op. 31 may at first glance be unsettling. But the pieces, in simple dance and song forms, display remarkable refinement. The collection, which already appeared in innumerable editions during Beethoven’s lifetime, enjoys great popularity to the present day, not least because – apart from the technically more demanding no. 5 – all the pieces are of medium difficulty, and thus are also accessible to proficient amateurs.Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827), the builder of imposing monuments for the keyboard required compositional diversions, needed to work from modest rather than mammoth blueprints. Apart from the several sonatas in which a relaxation of supreme striving is apparent, there are those pieces that are determinedly “small,” little things, or as Beethoven called them, Bagatelles, or Kleinigkeiten. An early set of the composer’s “little bits,” seven in number, were published in 1803 as Op. 33. Eleven pieces, Op. 119, came out in 1820, and the six of Op. 126, the last of his Bagatelles, were composed around 1823, the year he was finishing the Ninth Symphony, the Missa solemnis, and the Diabelli Variations for piano.

In regard to the Bagatelles, Eric Blom (1888-1959), the distinguished English writer on music and a Beethoven scholar, says that, in spite of their modest size [or perhaps because of it], the Bagatelles “reveal [Beethoven’s] character more intimately than anything else he ever wrote. They are,” he continues, “if anything in music can be, self-portraits, whereas his larger compositions express not so much personal moods as ideal conceptions requiring sustained thought and an unchanging emotional disposition for many day or weeks – indeed in Beethoven’s case sometimes years. But these short pieces could be dashed off by the composer, whatever he felt like at the moment, while the fit was on him. No doubt,” Blom concedes [and well he should], “there is an element of exaggeration in this theory of a difference between composition on a large and small scale, but the fact remains that in the Bagatelles we have some perfect and almost graphically vivid sketches of Beethoven in his changeable daily moods, tender or gently humorous one morning and full of fury, rude buffoonery or ill-temper the next. Not even his letters, in which we may find all these turns of mind too, reveal him more clearly than that.”

Beethoven thoroughly revised his Bagatelles op 33 shortly before publication. At the same time, however, he was incredibly busy and worked on his Piano Concerto No. 3, the Symphony No. 2 and the oratorio “Christ on the Mount of Olives.” In the light of Beethoven’s rising fame, he may have felt that he needed to satisfy a growing demand from students and amateurs for easy pieces from his pen.

We find a simple and innocent tune in No. 1, garnished with plenty of ornamentation and light-hearted transitions. No. 2 has the character of a scherzo that humorously manipulates rhythm and accents, while No. 3 appears folk-like in its melody and features a delicious change of key in the second phrase. The A-Major Bagatelle No. 4 is essentially a parody of a musette with a stationary bass pedal, and the minor-mode central section offers harmonic variety.

Beethoven provides some musical humour in No. 5 as this playful piece is a parody of dull passagework. In a really funny moment, the music gets stuck on a single note repeated over and over, like Beethoven can’t decide what to do next. In the end, he decides to repeat what he has already written before. In No. 6, we find a tune of conflicting characters, with the first phrase being lyrical and the second phrase being tuneful. The beginning of No. 7 almost suggests Beethoven’s Waldstein Sonata.

The Rhapsodies, Op. 79, for piano were written by Brahms in 1879 during his summer stay in Portschach, when he had reached the maturity of his career. They were inscribed to his friend, the musician and composer Elisabeth von Herzogenberg. At the suggestion of the dedicatee, Brahms reluctantly renamed the sophisticated compositions from “Klavierstücke” (piano pieces) to “rhapsodies”.

No. 1 in B minor. Agitato is the more extensive piece, with outer sections in sonata form enclosing a lyrical, nocturne-like central section in B major and with a coda ending in that key.

No. 2 in G minor. Molto passionato, ma non troppo allegro is a more compact piece in a more conventional sonata form

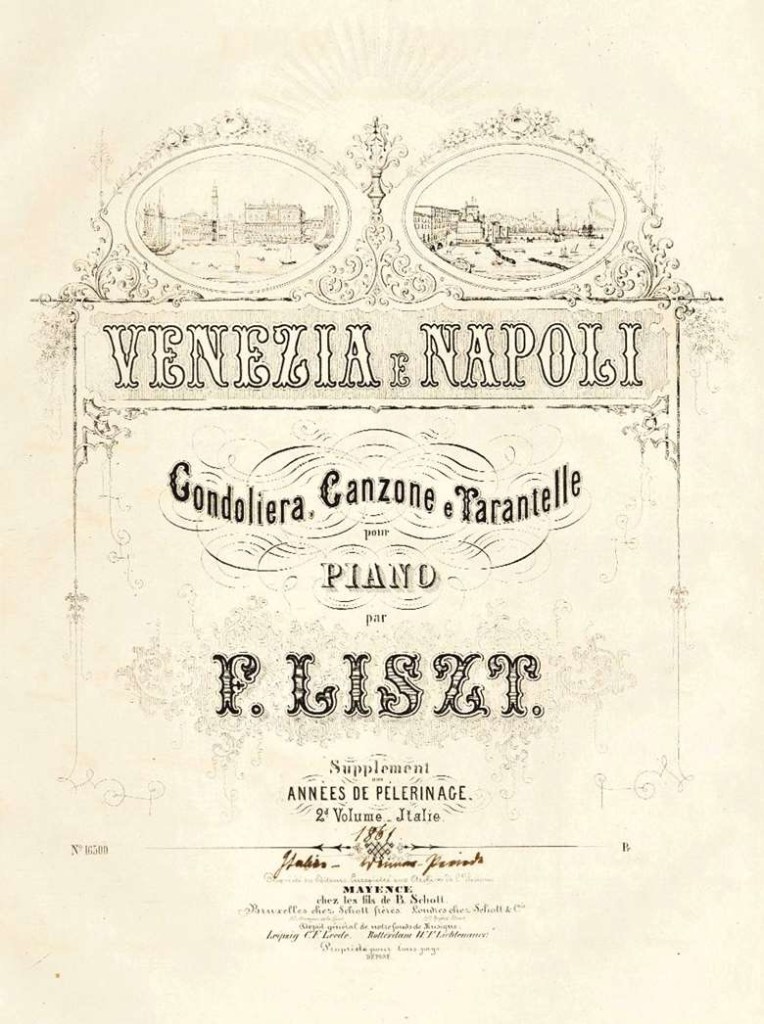

Venezia e Napoli are three pieces based on what was familiar material in the streets of Italy at the time.Gondoliera ,Canzone and Tarantella. Gabrielé played the last two which Liszt indicates in the score with a very specific pedal indication that they are to played as a pair.

Gondoliera is described by Liszt in the score as La biondina in gondoletta—Canzone di Cavaliere Peruchini (Beethoven’s setting of it, WoO157/12, for voice and piano trio just describes it as a Venetian folk-song). This is followed by a dark musing upon Rossini’s Canzone del Gondoliere—‘Nessùn maggior dolore’ (Otello) which itself recalls Dante’s Inferno (‘There is no greater sorrow than to remember past happiness in time of misery’); and the Tarantella—incorporating themes by Guillaume Louis Cottrau (1797–1847)—emerges from the depths, ultimately triumphantly boisterous. The ominous hemidemisemiquaver tremolos, quotes from Act 3 of Rossini’s opera – Dante’s ‘There is no greater sorrow than to recall in misery the time when we were happy’ (Inferno, Canto V). The Tarantella’s arabesque-variations elaborate two canzoni of the day by the Frenchman Guillaume Louis Cottrau (1797-1847), included in his Passatempi musicali (‘Musical Pastimes’), printed in Naples in 1824: ‘Lu milo muzzicato’, generating the theme, key and D flat shifts of the opening third, and ‘Fenesta vascia’ – the ‘Canzona napolitana’ of the middle section, familiar (in varied form, its first bar scalic/diatonic rather than gapped/chromaticised) from Thalberg’s 1853 L’art du chant appliqué au piano (No 24).

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2024/12/25/point-and-counterpoint-2024-a-personal-view-by-christopher-axworthy/

Grieg’s Piano Concerto with the Kauno miesto simfoninis orkestras and Maestro Markus Huber on Valentine’s Day!

What a wonderful reunion with this incredible Orchestra and Conductor after 4 years. Receiving a full standing ovation in a sold out Kauno valstybinė filharmonija was something I have been dreaming of for years ![]()

![]()

Also, I think it is fair to say that my support team is THE BEST! ![]() Thank you to my family, friends, teachers and all the people who came to my performance with the KMSO last Friday. The amount of love (and flowers!) I received was absolutely incredible! AČIŪ!!!

Thank you to my family, friends, teachers and all the people who came to my performance with the KMSO last Friday. The amount of love (and flowers!) I received was absolutely incredible! AČIŪ!!! ![]()

![]()

Šis koncertas buvo skirtas Jums, teta Stefa ![]()