From the very first notes of Dénes Várjon’s solo recital it was clear that here was a representative of the great Hungarian school of piano playing . The school of Dohnányi epitomised by the fluidity of sound as exemplified by Geza Anda but also that influenced the unmistakable sound of György Sándor, Peter Frankl ,Tamas Vasary,Andor Foldes and Andras Schiff.

A sound of such clarity and luminosity that one can only marvel at the completely relaxed and masterly musicianship that pours naturally from their body.

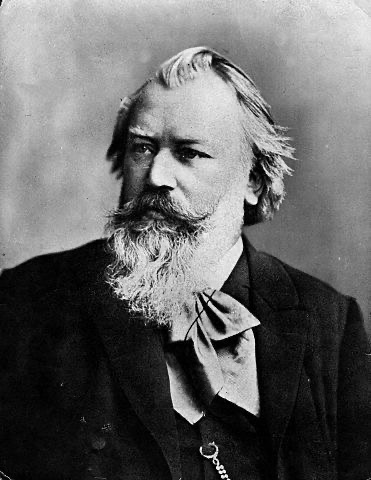

If I had not seen Alfred Brendel in the audience I would have sworn that this was his reincarnation on stage of the era when pianists were kapellmeisters. When Kempff with his long arms outstretched like we see in the caricature of Brahms, a musician who had digested the music for a lifetime and would arrive in the recording studio asking what they would like him to play!

And it was Brahms that opened the concert tonight by a musician we are more often used to seeing in partnership with other remarkable Hungarian musicians like Miklos Perenyi than on his own.

‘Presto energico’ Brahms writes and it was with this hurricane of energy that Dénis Várjon immediately started his recital .A wave of beautiful glowing resonant sounds almost orchestral in its concept. A grandeur sweeping all before it and immediately establishing his credentials as a master musician fearless in the face of sharing the message of the music entrusted to his wonderfully well oiled technical mastery. The sweeping left hand octaves were like great waves of sound ,never hard but always with a flowing fluidity like gasps of astonishment. It contrasted with the crystal clear resonance he brought to the Intermezzo in A minor. The crystalline clarity and delicacy he brought to the central episode was quite breathtaking and was like opening a window in a sultry atmosphere and letting fresh air in. The Capriccio in G minor was a whirlwind of sounds of passion and drive with the sumptuous full string orchestral sound of ‘un poco meno Allegro’, before the breathtaking depth and astonishing exhilaration of the final pages. There was a naked beauty to the Intermezzo in E with inner emotions revealed of innocence and desolate beauty. An etherial central episode of quite ravishing beauty before the questioning and searching of the Intermezzo in E minor. Finding solace in the mellifluous outpouring ‘dolce’ Brahms marks, and so his final questioning was ever more whispered ‘dolcissimo’.The Intermezzo in E that follows was a deeply melancholic outpouring as beauty is suddenly seen on the horizon, revealed with unashamed romantic abandon. And a wild abandon in the final Capriccio that was a cauldron of red hot emotions and an intricate web of sounds that flew from the pianist’s hands with silf like perfection. An astonishing performance that I have not heard played in public with the simplicity and mastery that we were treated to today since Kempff and Brendel’s unforgettable performances.

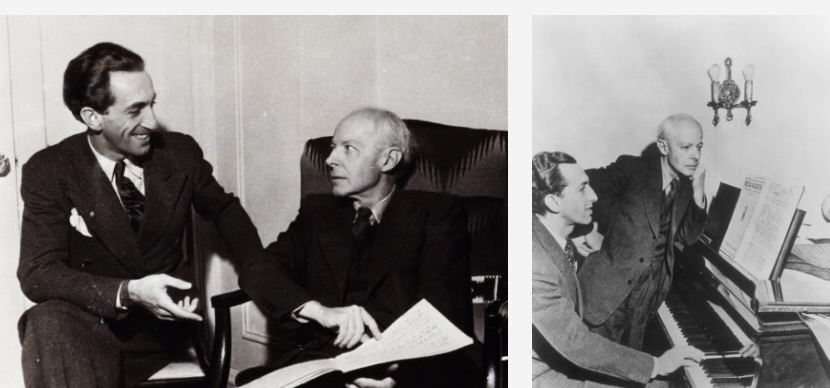

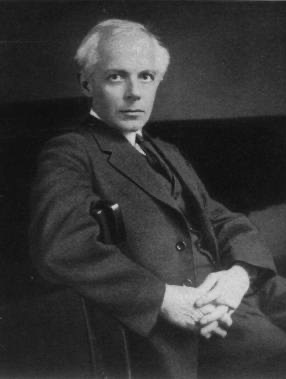

The Bartók dance suite followed that brought back memories of the many recitals that Sándor gave for us in Rome. The clarity and rhythmic precision with a kaleidoscope of colours and rhythmic variations that brought so vividly to life the Hungarian Dance idioms. Dénes Várjon played it with extraordinary conviction and energy with a breathtaking tour de force of mastery.There were music box sounds ,the mysterious drone of the bagpipes and the simple melodic lines doubled at the octave adding extraordinary flavour to music that is rarely heard in the concert hall.

The second half of the programme was dedicated to some of the most popular works from the romantic piano repertoire. Liszt ‘Les jeux d’eau à la Villa d’Este’ was played with a refined tonal palette of radiance and beauty that brought to life the imagery that Liszt can so miraculously depict. The gentle sprays of water played with whispered glistening delicacy just as the great monumental fountains brought forth sumptuous rich sounds of magnificence and grandeur.

Six of Chopin’s most loved pieces followed and were played with simplicity and a musicianship that was refreshing for its lack of rhetoric as the music was allowed to unfold so naturally. The Fantasie- Impromptu flowed with the same grace and beauty he had brought to Liszt, with a jeux perlé of undulating grace and passion.The final entry of the melody in the tenor register with the undulating accompaniment above was quite memorable as was the simple glowing beauty of the D flat nocturne that followed. A sense of balance that allowed the bel canto to sing with disarming simplicity as the embellishments were merely whispered streams of sounds of magical beauty. The two studies op 25 n. 1 and 2 were played with a refined sensibility where in the A flat study the melodic line just floated an a carpet of magical sounds. And it was these same sounds that spun a golden web around the second study.The Mazurka in B flat minor was played with the same robust dance character that he had brought to Bartók but there was also a sense of mystery and fantasy that made one realise why Schumann had described the Mazurkas as ‘canons covered in flowers’. The Fantasy in F minor suffered from a fluctuation of tempo and his holding up before the climax of the octave embellishments was rather disturbing, but of course there were many beautiful things not least the ravishing beauty of the central episode or the magic he brought to the final page with the long pedals allowing Chopin’s final thoughts to resonate with whispered simplicity.

It was curious though that whilst Dénis Várjon’s Brahms and Bartók had been so overwhelming I found the Liszt and Chopin lacking in the aristocratic weight and variety of sounds. Whilst his wonderfully fluid sound had created remarkable orchestral sounds suited to the two B’s but had belied the velvet rich beauty of the refined aristocratic world of Chopin.

Two encores by Bartók showed us where this pianist’s heart really lies and were truly breathtaking and exhilarating performances rarely heard in the concert hall.

Dénes Várjon

His sensational technique, deep musicality, wide range of interest have made Dénes Várjon one of the most exciting and highly regarded participants of international musical life. He is a universal musician: excellent soloist, first-class chamber musician, artistic leader of festivals, highly sought–after piano pedagogue. Widely considered as one of the greatest chamber musicians, he works regularly with preeminent partners such as Steven Isserlis, Tabea Zimmermann, Kim Kashkashian, Jörg Widmann, Leonidas Kavakos, András Schiff , Heinz Holliger, Miklós Perényi, Joshua Bell. As a soloist he is a welcome guest at major concert series, from New York’s Hall to Vienna’s Konzerthaus and London’s Wigmore Hall. He is frequently invited to work with many of the world’s leading symphony orchestras (Budapest Festival Orchestra, Tonhalle Orchestra, Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra, St. Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra, Chamber Orchestra of Europe, Russian National Orchestra, Kremerata Baltica, Academy of St. Martin in the Fields). Among the conductors he has worked with we find Sir Georg Solti, Sándor Végh, Iván Fischer, Ádám Fischer, Heinz Holliger, Horst Stein, Leopold Hager, Zoltán Kocsis. He appears regularly at leading international festivals from Marlboro to Salzburg and Edinburgh. He also performs frequently with his wife Izabella Simon playing four hands and two pianos recitals together. In the past decade they organized and led several chamber music festivals, the most recent one being „kamara.hu” at the Franz Liszt Music Academy in Budapest. In recent years Mr. Várjon has built a close cooperation with Alfred Brendel: their joint Liszt project was presented, among others, in the UK and Italy. He has recorded for the Naxos, Capriccio and Hungaroton labels with critical acclaim. Teldec released his CD with Sándor Veress’s “Hommage à Paul Klee” (performed with András Schiff, Heinz Holliger and the Budapest Festival Orchestra). His recording “Hommage à Géza Anda”, (PAN-Classics Switzerland) has received very important international echoes. His solo CD with pieces of Berg, Janáček and Liszt was released in 2012 by ECM. In 2015 he recorded the Schumann piano concerto with the WDR Symphonieorchester and Heinz 1 Holliger, and all five Beethoven piano concertos with Concerto Budapest and András Keller.

Dénes Várjon graduated from the Franz Liszt Music Academy in 1991, where his professors included Sándor Falvai, György Kurtág and Ferenc Rados. Parallel to his studies he was regular participant at international master classes with András Schiff. Dénes Várjon won first prize at the Piano Competition of Hungarian Radio, at the Leó Weiner Chamber Music Competition in Budapest and at the Géza Anda Competition in Zurich. He was awarded with the Liszt, the Sándor Veress and the Bartók-Pásztory Prize. In 2020 he received Hungary’s supreme award in culture, the Kossuth Prize. Mr. Várjon works also for Henle’s Urtext Editions.

Johannes Brahms 7 May 1833 Hamburg 3 April 1897 (aged 63)Vienna

After an early focus on works for solo piano, including the three sonatas that Robert Schumann described as “veiled symphonies,” Brahms tended to employ his chosen instrument, the piano, in collaborative works, producing a variety of duo sonatas (with violin, cello, and clarinet), piano trios, piano quartets, and one piano quintet, as well as two more trios (one with horn and one with clarinet). His final efforts for solo keyboard were published in four sets of shorter works (Opp. 116-119), which appeared between 1891 and 1893.

These four sets of late solo piano pieces are all in effect abstract instrumental songs, though unfailingly idiomatic. (So much so, that he abandoned his attempt to orchestrate the immediately popular Intermezzo, Op. 117, No. 1.) All are in the A-B-A song form typical of character pieces and are as highly concentrated as his greatest songs.

Only the first of these groups (Op. 116) has a continuity that argues for continuous performance. The other sets range widely in tone and temperament, by turns reflective and pensive, then agitated and restless. The individual pieces carry different titles, but more than half are designated cryptically as intermezzos, including all three of Op. 117, all but two of the six in Op. 118, and three of the four in Op. 119. These intimate works are the offspring of a composer whose greatest love was music itself. Johannes Brahms presumably wrote the Fantasies op. 116 at the same time as the Intermezzi op. 117 in the summer of 1892 in Bad Ischl. His sojourn in the Salzkammergut obviously inspired Brahms to write music for solo piano, as a year later he worked on other cycles when he was there. Amongst these late melancholy piano pieces, op. 116 is in particular characterised by opposites. Four “dreamy” – according to Clara Schumann – intermezzi are juxtaposed with three “deeply passionate” capricci.Composed in 1892-93, Brahms’s piano pieces opp. 116 to 119 are the last collections that he wrote for the instrument. Particularly noteworthy is his use of ‘small forms’ accompanied by a further increase in musical expression compared to his earlier works. In November 1892 Clara Schumann, probably the secret dedicatee of these pieces, confided to her diary that they were ‘a true source of enjoyment, everything, poetry, passion, rapture, intimacy, full of the most marvellous effects […]. In these pieces I at last feel musical life re-enter my soul, and I play once more with true devotion.’

The Fantasies, op. 116, were composed in the Austrian resort of Bad Ischl in summer 1892. Clara described them ecstatically as ‘wonderfully original piano pieces’, four ‘dreamlike’ intermezzos and three ‘deeply passionate’ capriccios. The former are moderately difficult to play, while the capriccios require considerable virtuosity.

Béla Viktor János Bartók. 25 March 1881 Nagyszentmiklós,Hungary

26 September 1945 (aged 64) New York

In 1923, the Budapest city council threw a vast party to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the merging of the towns of Buda and Pest: two rather distinct although neighboring — on opposite banks of the Danube — entities: Buda, the old city, with its imperial traditions and aristocratic residences; Pest, the commercial hub and abode of both the middle class and the working class. The resultant city instantly became one of Europe’s major metropolitan areas. The commemoration of this marriage of convenience also represented a return to life for the entire nation of Hungary three years after the Treaty of Trianon, which dismembered the Austro-Hungarian Empire after its defeat in the First World War, divesting Hungary of half of its land, virtually all of its natural resources, and most of the ethnic minorities that made it the most diverse of European cultures. To cap the celebration the city fathers staged, among other events, a grand concert for which the country’s leading composers. Ernö Dohnányi, Béla Bartók, and Zoltán Kodály were each commissioned to contribute a score, all to be performed by the orchestra of the Budapest Philharmonic Society under Dohnányi’s baton. The concert, on November 19, 1923, was a partial success. Bartók’s contribution, the present Dance Suite, suffered the dread, proverbial “mixed reception,” which means it wasn’t much liked, but not disliked sufficiently to create a career-enhancing scandal. “My Dance Suite was so badly performed that it could not achieve any significant success,” Bartók wrote. “In spite of its simplicity there are a few difficult places, and our Philharmonic musicians were not sufficiently adult for them. Rehearsal time was, as usual, much too short, so the performance sounded like a sight-reading, and a poor one at that.” Two years later, however, the Suite was heard again, in the context of the International Society for Contemporary Music Festival in Prague, in a performance by the Czech Philharmonic under Václav Talich, and was rapturously received — with performances throughout Europe following. It did more for Bartók’s reputation, in the positive sense, than all his previous works combined. The work was frequently heard, but ill-used, during the post-World War II communist era in Hungary and elsewhere in Eastern Europe. While it may likely express its composer’s nostalgia for a Hungary that was, with its extraordinary ethnic mix, the post-World War II communist interpreters of history turned it into a “hymn of brotherhood of nations and people” — Hungarian, Romanian, Slovak, gypsy, and Arab. But the composer had earlier stated, simply, that “the Dance Suite was the result of my researches and love for folk music,” which he had been studying and recording since 1905. Nowhere did he suggest its possible function as a “hymn” to anything.

The five-part suite, in which all the tunes are Bartók’s own inventions rather than actual folk melodies, prominently — but not exclusively — employs Hungarian rhythms (2/4 and 4/4 abound). Finally after its great success, the director of Universal Edition ,Emil Hertzka , commissioned from him an arrangement for piano, which was published in 1925. However, he never publicly performed this arrangement, and it was premiered in March 1945, a few months before his death, by his friend György Sándor

This suite has six movements, even though some recordings conceive it as one single full-length movement. A typical performance of the whole work would last approximately fifteen minutes.

Moderato

Allegro molto

Allegro vivace

Molto tranquillo

Comodo

Finale Allegro