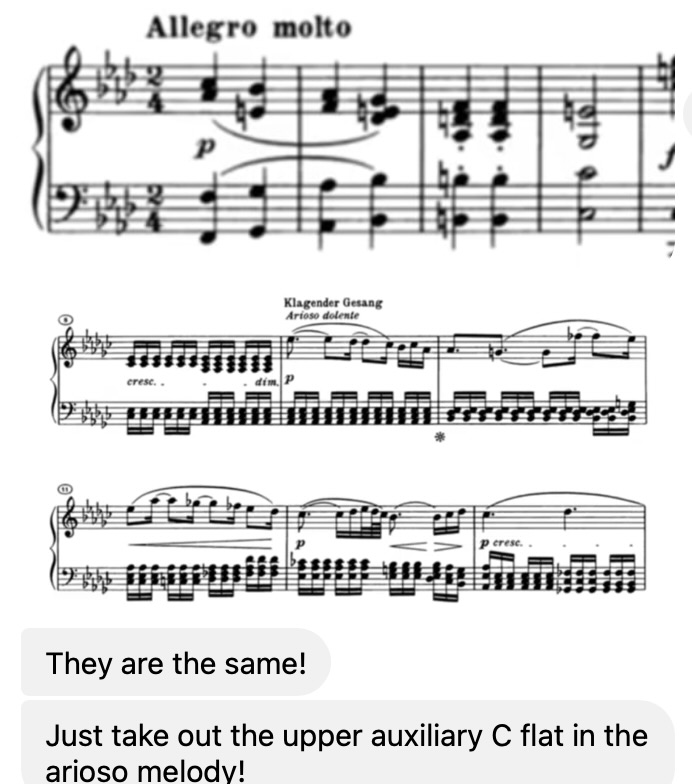

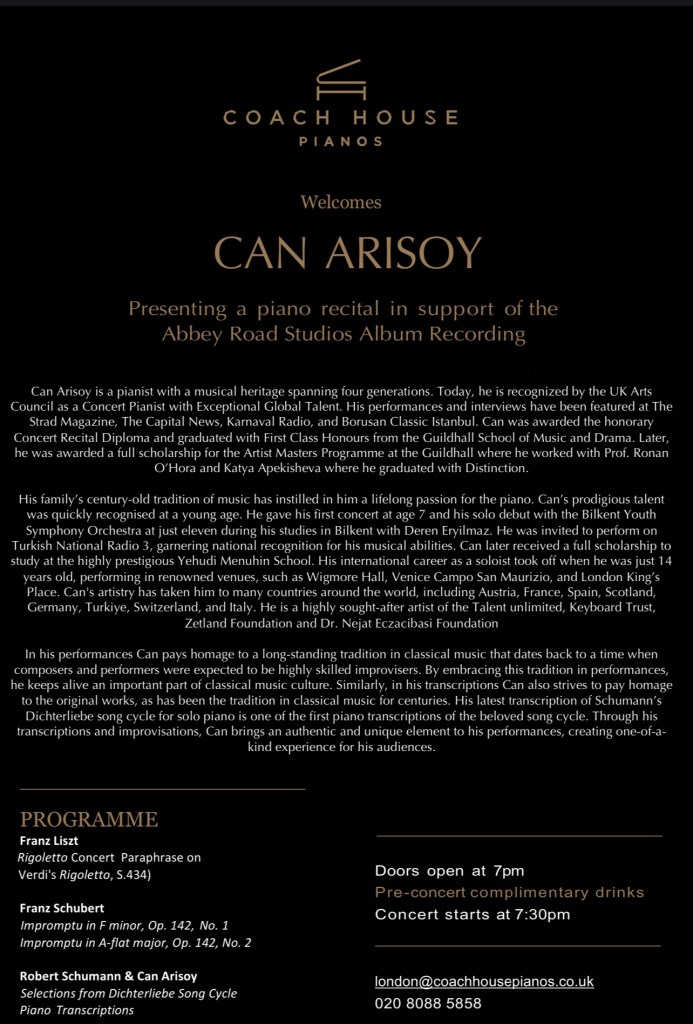

Can Arisoy became aware that there were actually no recordings of the transcriptions for solo piano of Schumann’s Dichterliebe even though there exist the transciptions of the Italian composer Gian Paolo Chiti. The transcriptions of Frédéric Meinders with Gian Paolo Chiti are strictly transcriptions but the pieces that Can wrote are solo piano arrangements where there was more freedom in the creative process.

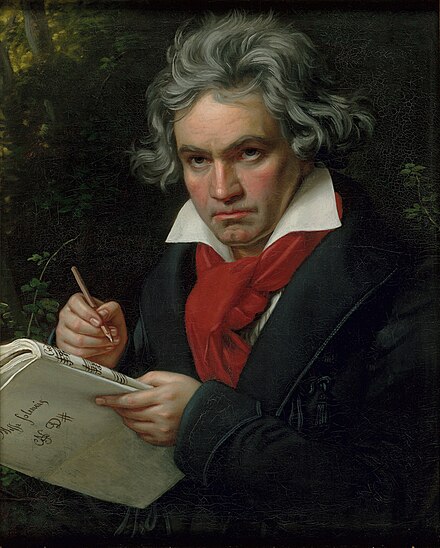

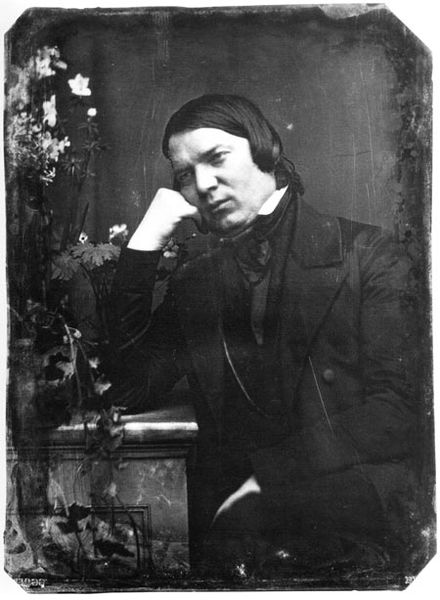

Liszt seemed to ignore the better known songs of Schumann and as Leslie Howard notes : ‘Some of Liszt’s Schumann transcriptions have withstood all vagaries of fashion and have featured in the repertoire of every generation of pianists, while others remain sadly unknown, as do some of the Schumann originals. Liszt’s choice of Schumann seems largely to ignore the well known and to investigate some of the later, most intimate works. Andersen’s ‘Christmas Song’ is really a very simple hymn, and ‘The Changing Bells’ is a straightforward setting of a little moral fable by Goethe in which a recalcitrant boy is frightened by a dream of bells into going to church as his mother has told him.

It may have been due to the appalling rudeness eventually shown to Liszt and his music by Clara Schumann—she removed his name from the dedication on Robert Schumann’s Fantasy, opus 17, and she rejected Liszt’s dedication to her of his Paganini Études. However Can has for sometime been preparing these transcriptions for piano solo and it is thanks to the encouragement of Coach House Pianos that there is a project to add a piano solo version of Dichterliebe to the CD catalogue.

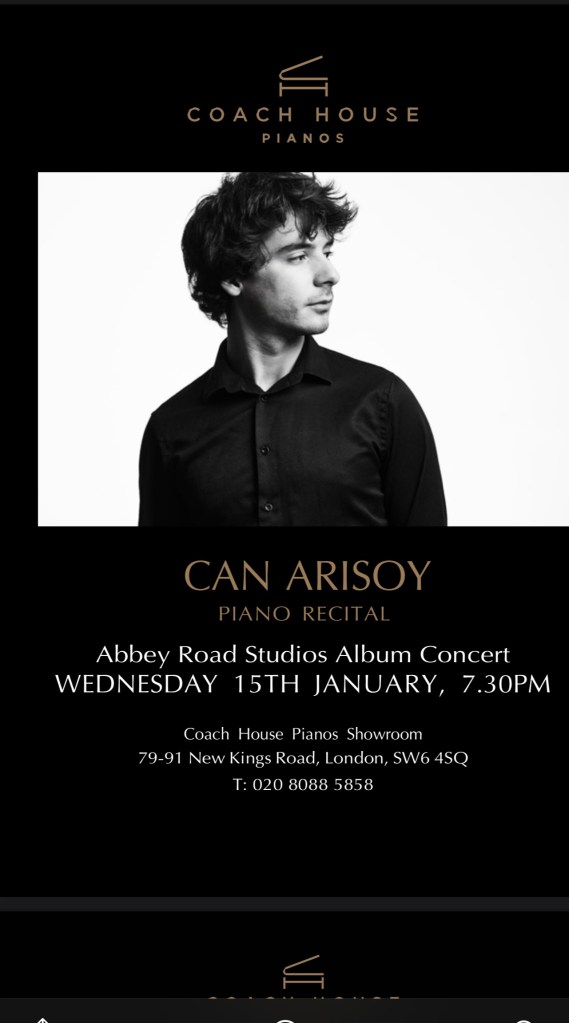

Can a true musician having received remarkable early training in musicianship from Marcel Baudet at the Yehudi Menuhin School,has dedicated his energy to creating these pianistic versions of Schumann, some more elaborate than others ( indeed one seemingly inspired by Pletnev). But basically the poetic message has been transformed into pianistic terms where so often music speaks much louder than words. How many great lieder are completed by the solo piano especially in the Dichterliebe reaching places where even the poetry of Heine is not enough? Playing a selection of 14 songs from the 16 of the Cycle, Can’s poetic playing created an atmosphere that filled the air, on his 25th birthday, with the rarified sounds of this magnificent Bösendorfer Imperial offered so generously by Can’s mentor at Coach House Pianos, David Halford.

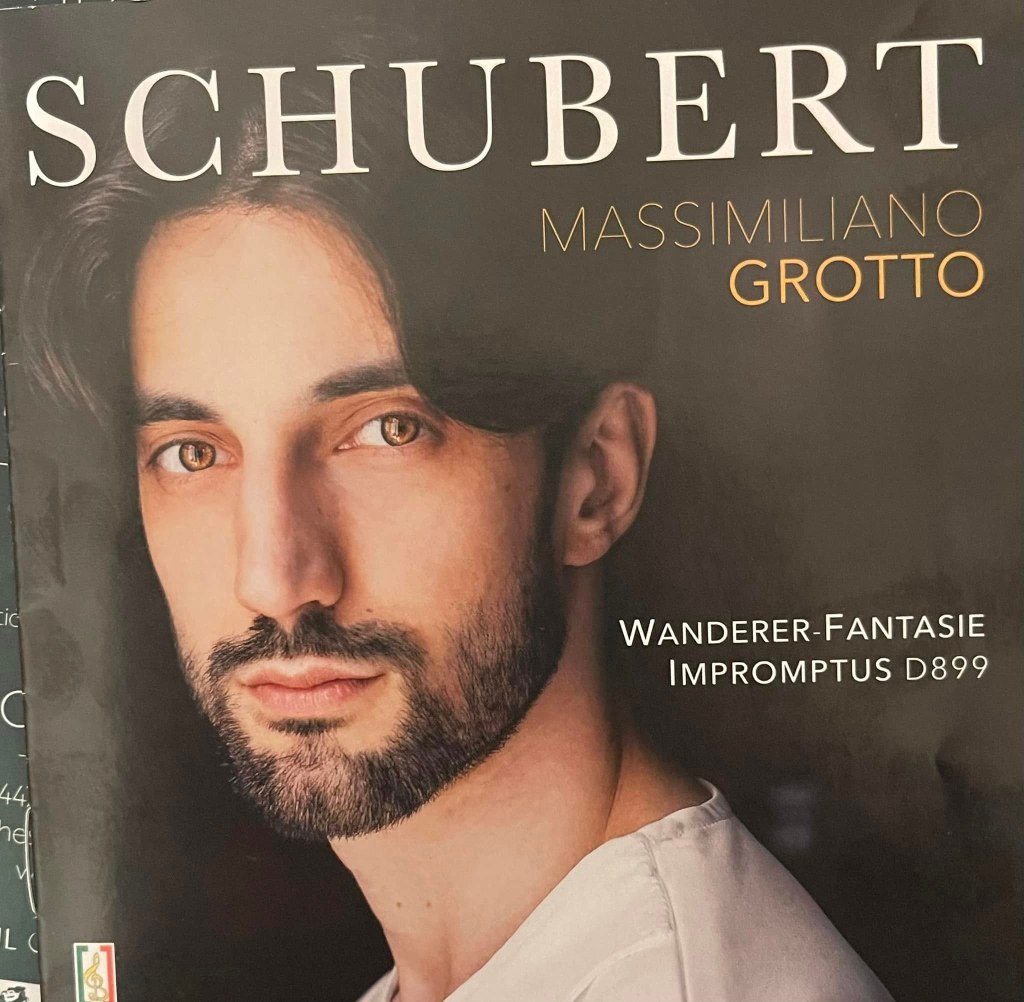

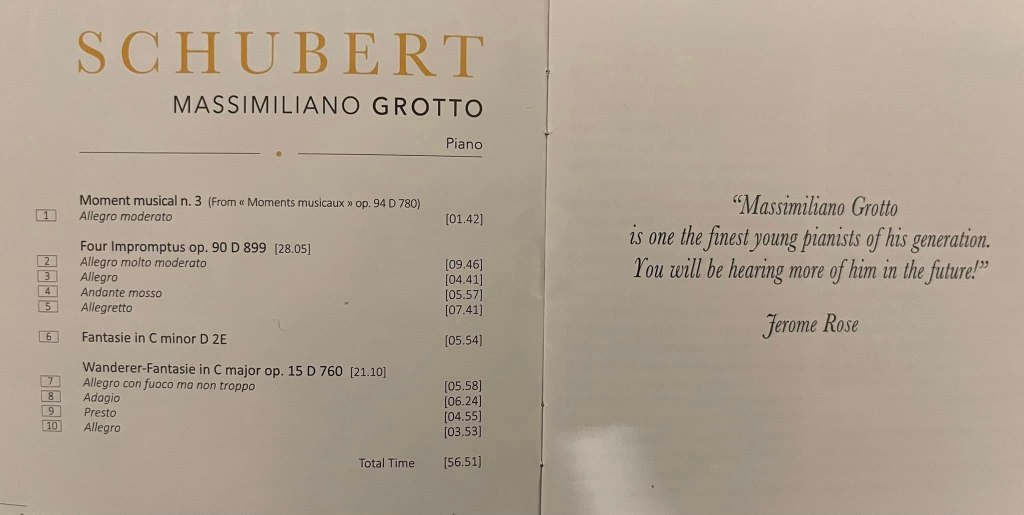

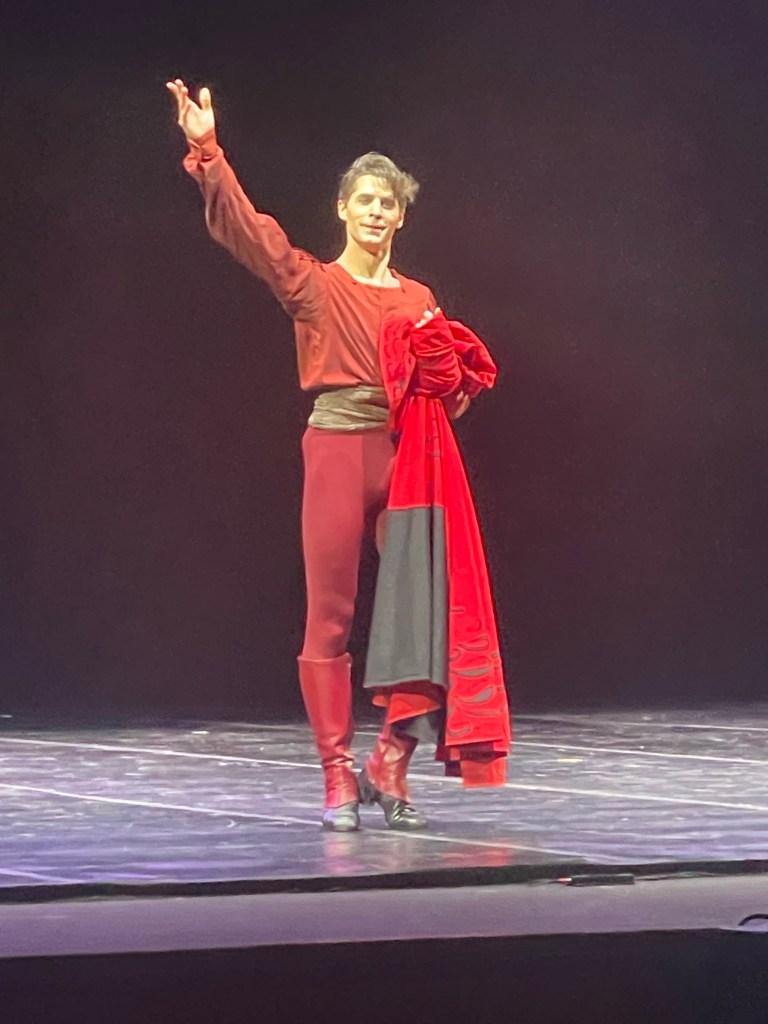

Opening his birthday party with one of the most perfect of Liszt’s operatic transcriptions, that of Verdi’s ‘Rigloletto’. Played with operatic abandon and great style with ravishing sounds and scintillating virtuosity. Everything Can plays is pure music and never a hard or ungrateful sound is to be heard from his agile fingers. Following with two Impromptu’s from Schubert’s second set, written in the last year of his all too short 31 years, Can showed his musical pedigree as he shaped these final mellifluous outpourings with heartrending simplicity and architectural understanding.

Drama and poetry united as indeed he has aspired to do in his own transcriptions of Schumann.

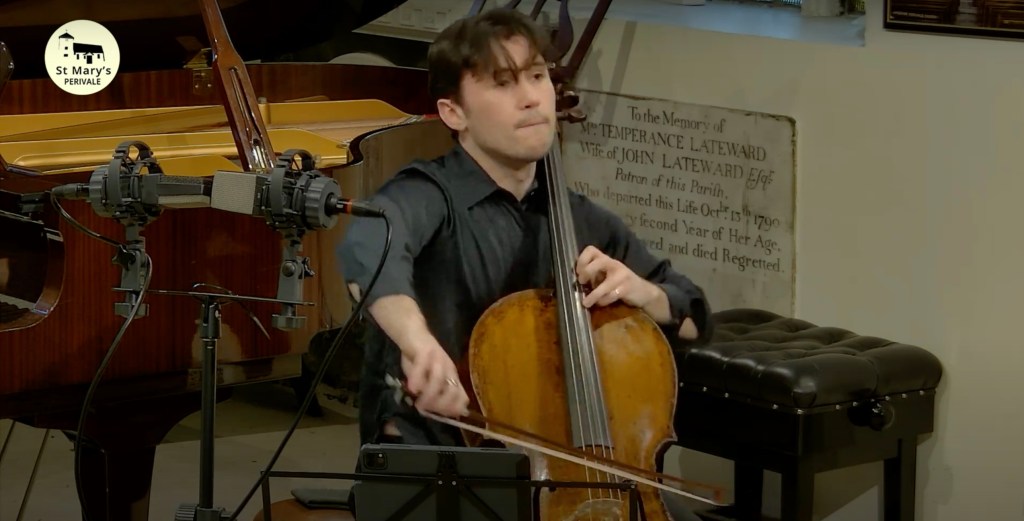

Brazil 200 and Keyboard Trust 30 a collaboration born on wings of Brazilian song

Can Arisoy Keyboard Trust New Artists Recital

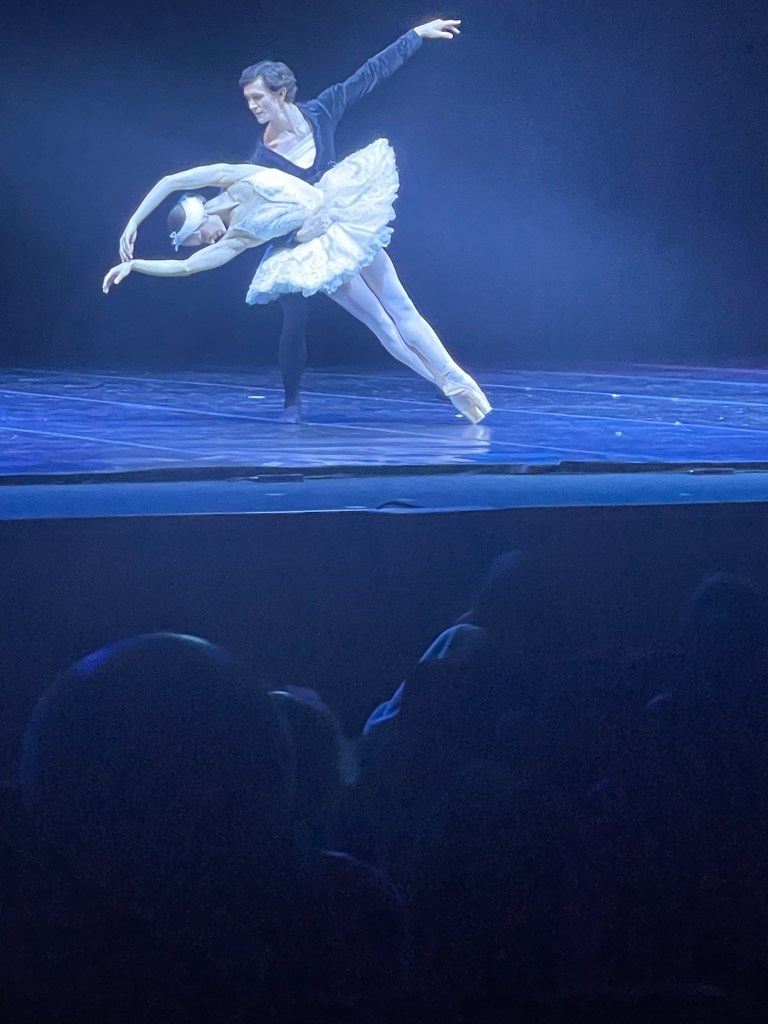

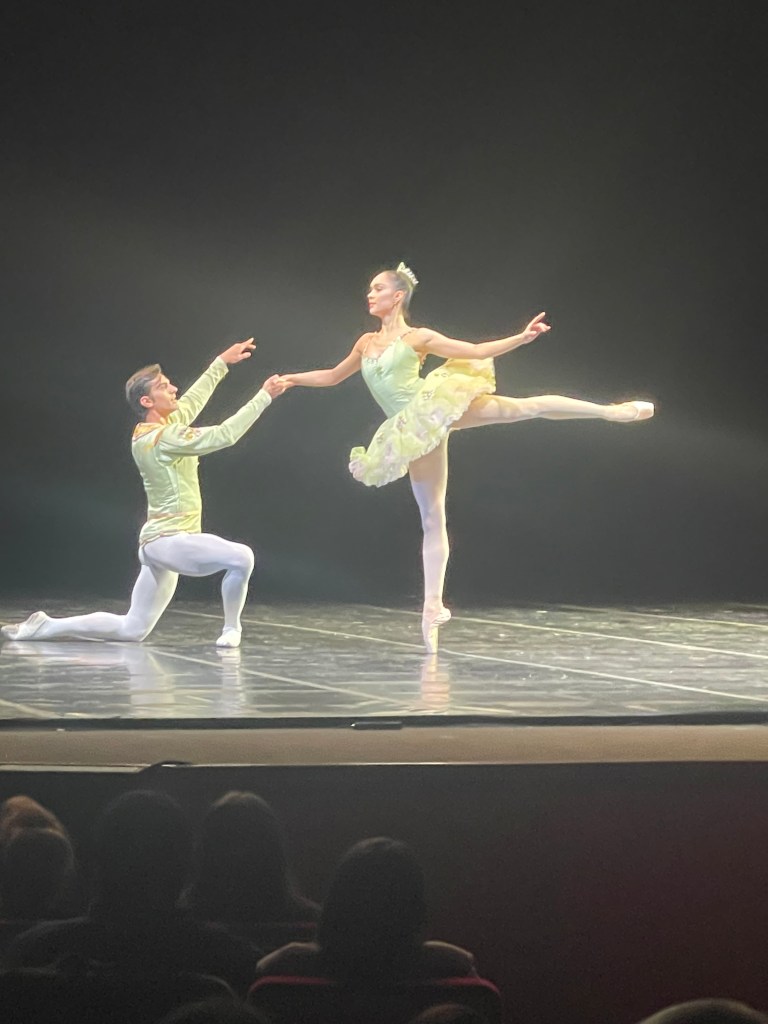

Can Arisoy Elfida su Turan Damir Durmanovic at St James’s Talent Unlimited presents music making at its most refined

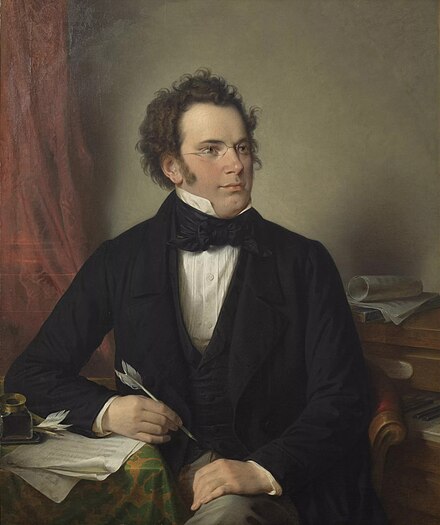

8 June 1810. Zwickau, Kingdom of Saxony – 29 July 1856 (aged 46) Bonn

Dichterliebe, A Poet’s Love op 48 was composed by Robert Schumann in 1840. The texts for its 16 songs come from the Lyrisches Intermezzo by Heinrich Heine, written in 1822–23 and published as part of Heine’s Das Buch der Lieder.The songs were composed in 1840, and the first edition of Dichterliebe was published in two volumes by Peters, in Leipzig , in 1844. In the original 1840 version with the 20 songs (originally dedicated to Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy), the cycle had the following, longer title: “Gedichte von Heinrich Heine – 20 Lieder und Gesänge aus dem Lyrischen Intermezzo im Buch der Lieder (“Poetry by Heinrich Heine – 20 Lyrics and Songs from the Lyric Intermezzo in the Book of Songs”)”. Though Schumann originally set 20 songs to Heine’s poems, only 16 of the 20 were included in the first edition. Dein Angesicht (Heine no. 5) is one of the omitted items. Auf Flügeln des Gesanges, On Wings of Song (Heine no 9), is best known from a setting by Mendelssohn.

The famed introduction to the first song, Im wunderschönen Monat Mai, is a direct quotation from Clara Wieck’s Piano Concerto in A minor (1835). It comes from the third beat of measure 30 through the second beat of measure 34 of the second movement. Robert uses the same key, same melodic pattern, similar accompaniment textures, tempo and rhythmic patterns in measures 1 through 4 of the opening to Dichterliebe.

Although often associated with the male voice, Dichterliebe was dedicated to the soprano Wilhelmina Schröder-Devrient] so the precedent for performance by female voice is primary. The first complete public recital of the work in London was given by Harry Plunket Greene , accompanied from memory by Leonard Borwick, on 11 January 1895 at London’s St James’s Hall.

- Im wunderschönen Monat Mai (Heine, Lyrical Intermezzo no 1). (“In beautiful May, when the buds sprang, love sprang up in my heart: in beautiful May, when the birds all sang, I told you my desire and longing.”)

- Aus meinen Tränen sprießen (Heine no 2). (“Many flowers spring up from my tears, and a nightingale choir from my sighs: If you love me, I’ll pick them all for you, and the nightingale will sing at your window.”)

- Die Rose, die Lilie, die Taube, die Sonne (Heine no 3). (“I used to love the rose, lily, dove and sun, joyfully: now I love only the little, the fine, the pure, the One: you yourself are the source of them all.”)

- Wenn ich in deine Augen seh (Heine no 4). (“When I look in your eyes all my pain and woe fades: when I kiss your mouth I become whole: when I recline on your breast I am filled with heavenly joy: and when you say, ‘I love you’, I weep bitterly.”)

- Ich will meine Seele tauchen (Heine no 7). (“I want to bathe my soul in the chalice of the lily, and the lily, ringing, will breathe a song of my beloved. The song will tremble and quiver, like the kiss of her mouth which in a wondrous moment she gave me.”)

- Im Rhein, im heiligen Strome (Heine no 11). (“In the Rhine, in the sacred stream, great holy Cologne with its great cathedral is reflected. In it there is a face painted on golden leather, which has shone into the confusion of my life. Flowers and cherubs float about Our Lady: the eyes, lips and cheeks are just like those of my beloved.”)

- Ich grolle nicht (Heine no 18). (“I do not chide you, though my heart breaks, love ever lost to me! Though you shine in a field of diamonds, no ray falls into your heart’s darkness. I have long known it: I saw the night in your heart, I saw the serpent that devours it: I saw, my love, how empty you are.”)

- Und wüßten’s die Blumen, die kleinen (Heine no 22). (“If the little flowers only knew how deeply my heart is wounded, they would weep with me to heal my suffering, and the nightingales would sing to cheer me, and even the starlets would drop from the sky to speak consolation to me: but they can’t know, for only One knows, and it is she that has torn my heart asunder.”)

- Das ist ein Flöten und Geigen (Heine no 20). (“There is a blaring of flutes and violins and trumpets, for they are dancing the wedding-dance of my best-beloved. There is a thunder and booming of kettle-drums and shawms. In between, you can hear the good cupids sobbing and moaning.”)

- Hör’ ich das Liedchen klingen (Heine no 40). (“When I hear that song which my love once sang, my breast bursts with wild affliction. Dark longing drives me to the forest hills, where my too-great woe pours out in tears.”)

- Ein Jüngling liebt ein Mädchen (Heine no 39). (“A youth loved a maiden who chose another: the other loved another girl, and married her. The maiden married, from spite, the first and best man that she met with: the youth was sickened at it. It’s the old story, and it’s always new: and the one whom she turns aside, she breaks his heart in two.”)

- Am leuchtenden Sommermorgen (Heine no 45). (“On a sunny summer morning I went out into the garden: the flowers were talking and whispering, but I was silent. They looked at me with pity, and said, ‘Don’t be cruel to our sister, you sad, death-pale man.'”)

- Ich hab’ im Traum geweinet (Heine no 55). (“I wept in my dream, for I dreamt you were in your grave: I woke, and tears ran down my cheeks. I wept in my dreams, thinking you had abandoned me: I woke, and cried long and bitterly. I wept in my dream, dreaming you were still good to me: I woke, and even then my floods of tears poured forth.”)

- Allnächtlich im Traume (Heine no 56). (“I see you every night in dreams, and see you greet me friendly, and crying out loudly I throw myself at your sweet feet. You look at me sorrowfully and shake your fair head: from your eyes trickle the pearly tear-drops. You say a gentle word to me and give me a sprig of cypress: I awake, and the sprig is gone, and I have forgotten what the word was.”)

- Aus alten Märchen winkt es (Heine no 43). “(The old fairy tales tell of a magic land where great flowers shine in the golden evening light, where trees speak and sing like a choir, and springs make music to dance to, and songs of love are sung such as you have never heard, till wondrous sweet longing infatuates you! Oh, could I only go there, and free my heart, and let go of all pain, and be blessed! Ah! I often see that land of joys in dreams: then comes the morning sun, and it vanishes like smoke.”)

- Die alten, bösen Lieder (Heine no 65). (“The old bad songs, and the angry, bitter dreams, let us now bury them, bring a large coffin. I shall put very much therein, I shall not yet say what: the coffin must be bigger than the great tun at Heidelberg. And bring a bier of stout, thick planks, they must be longer than the Bridge at Mainz. And bring me too twelve giants, who must be mightier than the Saint Christopher in the cathedral at Cologne. They must carry away the coffin and throw it in the sea, because a coffin that large needs a large grave to put it in. Do you know why the coffin must be so big and heavy? I will put both my love and my suffering into it.”)