Playing of great authority and superb musicianship by Massimiliano Grotto where the elegance and Viennese charm of Schubert’s ‘Valses Nobles’ were answered by the deep meditation of his second ‘Klavierstücke’. Heralding his extraordinary vision, like Beethoven’s final pianistic trilogy, of what he could forsee at the end of an all too brief terrestrial existence.

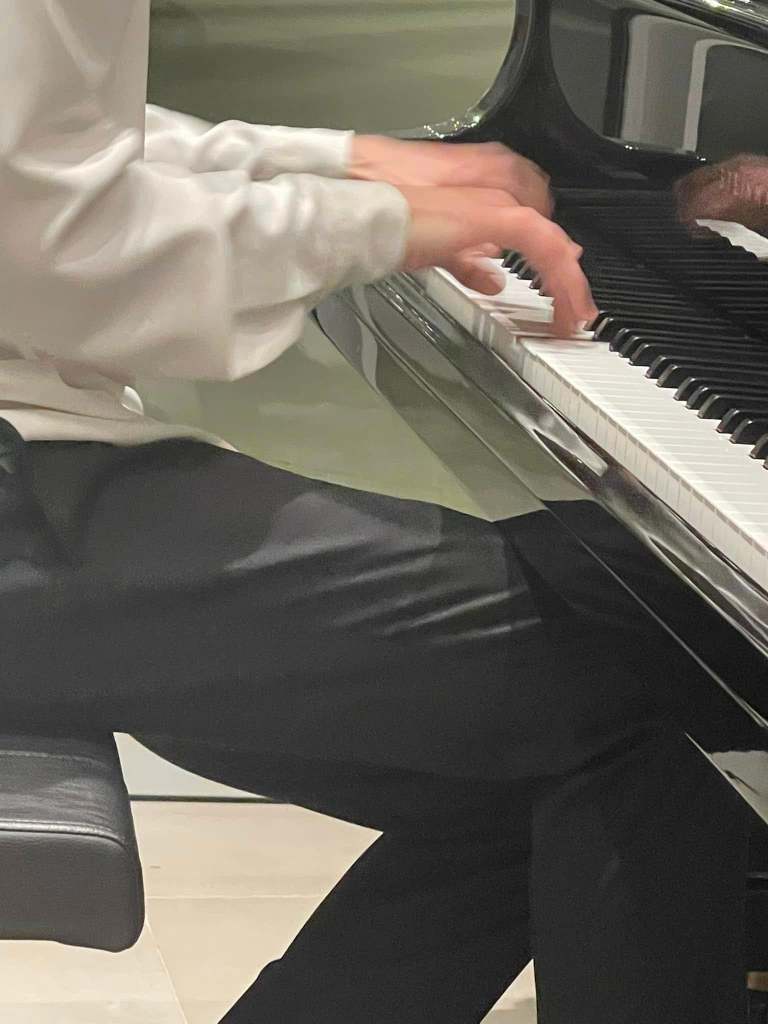

Massimiliano playing with commanding assurance as the Beethovenian call to arms at the opening of his C minor Sonata was enacted with overwhelming impact.

So many differing emotions that could be conveyed as one complete whole of conviction. There was an extraordinary clarity and demonic rhythmic drive of intensity and profound understanding of this dark place that Schubert was to envisage before the vision of peace and light that he was to find in the final sonata of his trilogy, written in the last year of his 31 years on this earth.

Even the ‘Adagio’ was penned with great strokes of burning intensity and poignant meaning always with the menace looking on from afar. But there was the glorious relief of the gentle return of the opening melody with a barely etched accompaniment. Some playing of masterly control and use of the pedals as the theme was allowed to float with simplicity and innocence leading into the beautifully fluid ‘Menuetto’ and richly textured ‘Trio.’ The Tarantella finale took flight with the same authority and conviction that I remember from Richter many years ago in London. Even the sudden rays of sunlight that Schubert‘s genius could never fully suppress had the same feeling of whirlwind energy.

A remarkable performance from a pianist who is above all a superb musician. One that can see the burning genius of Schubert in an architectural shape with four seemingly diverse movements, transformed into a unified visionary journey of discovery.

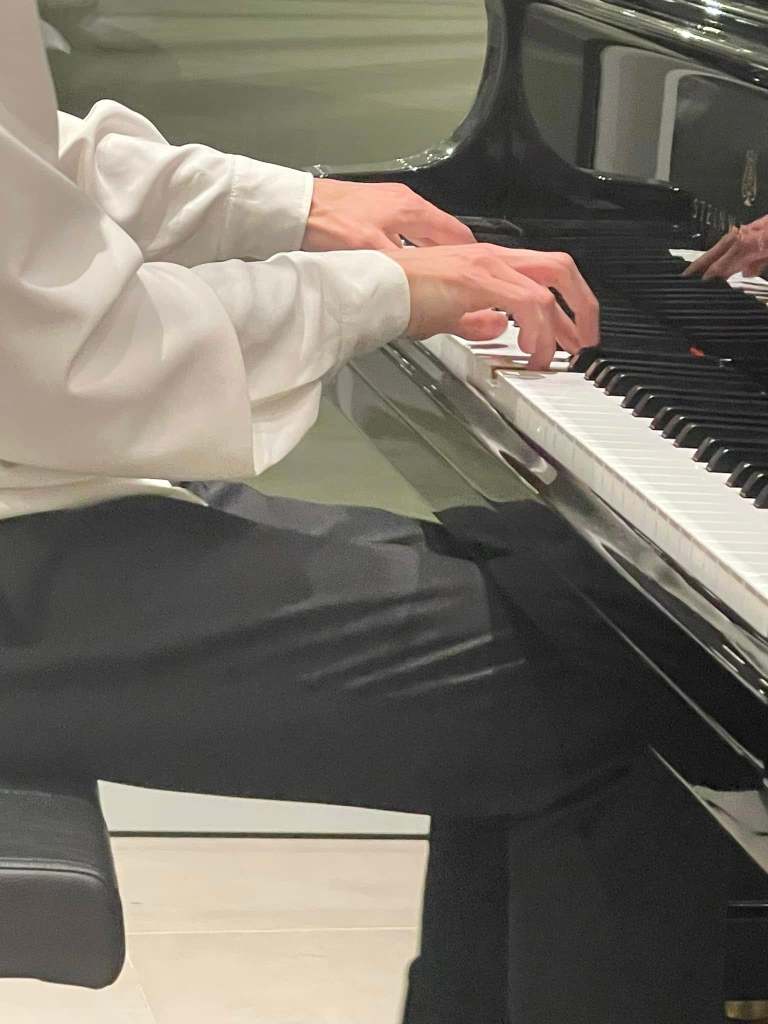

The second of the ‘Klavierstücke’ rarely heard just on its own, in Massimiliano’s poetic hands was turned into a tone poem of ravishing beauty and searing intensity. A beautiful mellifluous outpouring with a kaleidoscope of subtle colours allowed to flow so gracefully on not always untroubled waters. There was the dynamic menace to the driving rhythms of the first contrasting episode and the passionate outpouring of the second with a melodic line etched with great intensity. Many interesting bass counterpoints were underlined with refined good taste and brought the music vividly alive as Massimiliano’s masterly musicianship knew that Schubert’s roots were firmly created from the bass upwards.

The twelve ‘Valses Nobles’ were played as a whole with contrasts that ranged from Viennese elegance to rhythmic drive and the delicacy of bel canto. Nobility and majesty too and one in particular that Liszt could not resist turning into his own ‘Soirée de Vienne.’

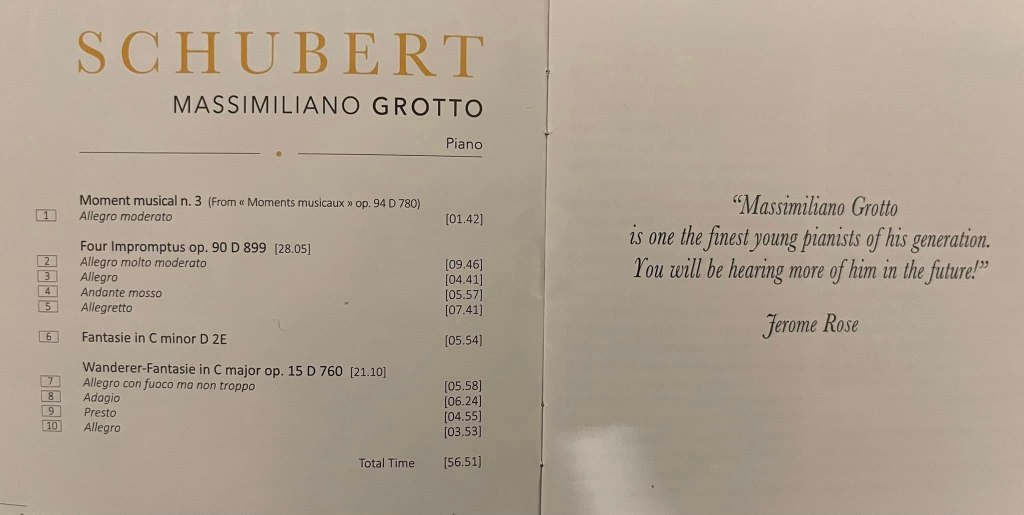

The Moment Musicaux n 3 in F minor, offered as an encore, was played with beguiling rhythmic insinuation and also a certain freedom to elaborate on Schubert’s own ornamentation.

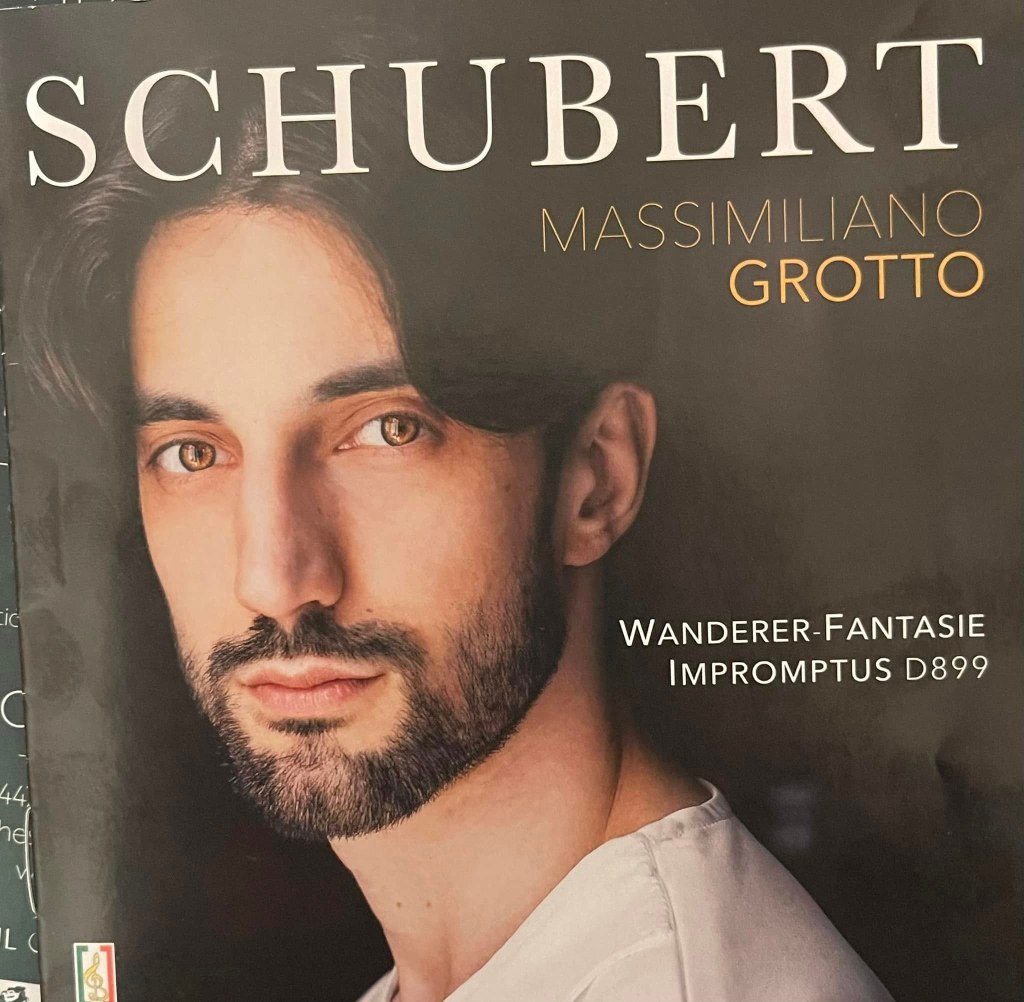

Jerome Rose, Massimiliano’s mentor in New York, played Schubert in a recital in my series in Rome some years ago and I can only endorse what he has said about Massimiliano : ‘ one of the finest pianists of his generation. You will be hearing more of him in the future.’

Bravo too, Valerio Vicari, and his dedicated team who offer a platform to so many wonderful young players who after years of dedication all they crave is an audience with whom they can share their considerable artistry..

Schubert wrote about a hundred waltzes for piano solo. Particularly well known among these are two named collections, the 34 Valses Sentimentales (op. 50, D.779) and the 12 Valses Nobles (op 77 Op.D.969).The Valses Sentimentales were written in 1823, and the Valses Nobles are believed to have been written in 1827, the year before Schubert’s death, although the manuscript is undated.

The last three sonatas, D. 958, 959 and 960, are his last major compositions for solo piano. They were written during the last months of his life, between the spring and autumn of 1828, but were not published until about ten years after his death, in 1838–39. Like the rest of Schubert’s piano sonatas, they were mostly neglected in the 19th century. By the late 20th century, however, public and critical opinion had changed, and these sonatas are now considered among the most important of the composer’s mature masterpieces. They are part of the core piano repertoire, appearing regularly on concert programs and recordings.The last year of Schubert’s life was marked by growing public acclaim for the composer’s works, but also by the gradual deterioration of his health. On March 26, 1828, together with other musicians in Vienna, Schubert gave a public concert of his own works, which was a great success and earned him a considerable profit. In addition, two new German publishers took an interest in his works, leading to a short period of financial well-being. However, by the time the summer months arrived, Schubert was again short of money and had to cancel some journeys he had previously planned.

Schubert had been struggling with syphilis since 1822–23, and suffered from weakness, headaches and dizziness. However, he seems to have led a relatively normal life until September 1828, when new symptoms such as effusions of blood appeared. At this stage he moved from the Vienna home of his friend Franz von Schober to his brother Ferdinand’s house in the suburbs, following the advice of his doctor; unfortunately, this may have actually worsened his condition. However, up until the last weeks of his life in November 1828, he continued to compose an extraordinary amount of music, including such masterpieces as the three last sonatas.

Schubert probably began sketching the sonatas sometime around the spring months of 1828; the final versions were written in September. These months also saw the appearance of the Three Piano Pieces D .946, the Mass in E flat D.950, the String Quintet D.956, and the songs published posthumously as the Schwanengesang collection (D. 957 and D. 965A), among others. The final sonata was completed on September 26, and two days later, Schubert played from the sonata trilogy at an evening gathering in Vienna. In a letter to Probst (one of his publishers), dated October 2, 1828, Schubert mentioned the sonatas amongst other works he had recently completed and wished to publish.However, Probst was not interested in the sonatas, and by November 19, Schubert was dead.

In the following year, Schubert’s brother Ferdinand sold the sonatas’ autographs to another publisher, Anton Diabelli , who would only publish them about ten years later, in 1838 or 1839. Schubert had intended the sonatas to be dedicated to Johann Nepomuk Hummel , whom he greatly admired. Hummel was a leading pianist, a pupil of Mozart, and a pioneering composer of the Romantic style (like Schubert himself). However, by the time the sonatas were published in 1839, Hummel was dead, and Diabelli, the new publisher, decided to dedicate them instead to composer Robert Schumann, who had praised many of Schubert’s works in his critical writings.