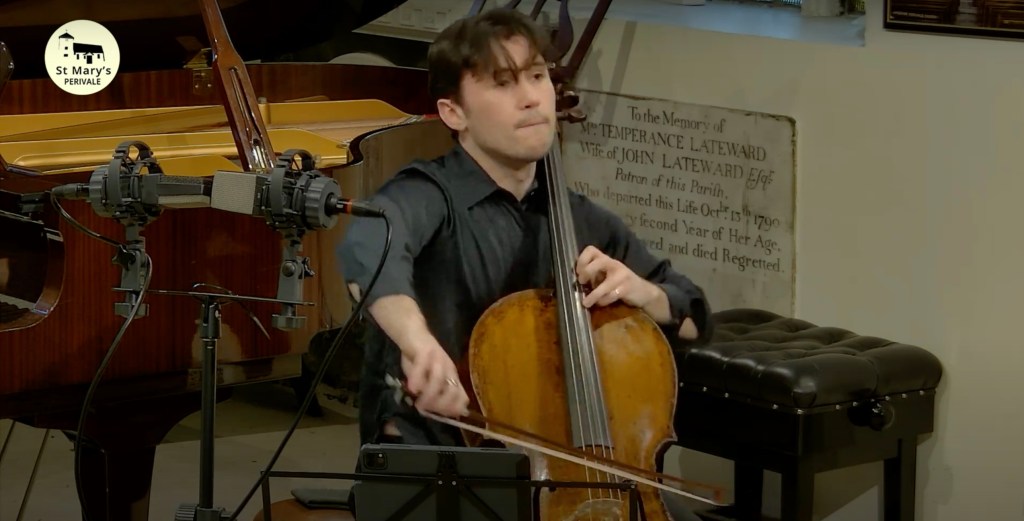

Some fine duo playing for the first concert in the 2025 season at St Mary’s ,the first of over a hundred already programmed for the future! Ke Ma I have heard many times as a solo pianist but this is the first time as an equal partner to a cellist.Finn a young cellist from Scotland who is now studying in Switzerland and already at 22 shows a maturity and mastery which will grow as his playing gains in even more weight.

Beethoven variations played with a great sense of character with a question and answer between the two players of tenderness and elegance quite apart from their dynamic rhythmic drive.The beautiful piano solo in the minor was answered by the cello with delicacy and nobility.A playful ‘joie de vivre’ between the two instruments with a joyous ending where as always the genius of Beethoven has some surprises up his sleeve that were played with innocent abandon.

The first of the Schumann Fantasiestucke was played tenderly with expression but seemed to lack the sweep and expansive line that is so much part of Schumann’s mellifluous output.It seemed to take flight with the central episode of the second piece that was played with quixotic lightness with a superb sense of ensemble between these two players now totally united in Schumann’s unpredictable changes of mood and character.Straight into the last piece with the treacherous opening played with wild abandon and mastery.Here now they both played with a great sense of architectural line with passionate intensity of great abandon and romantic fervour.

Now completely attuned to each other they gave a performance of the Franck Sonata of passionate intensity and masterly technical control.There was a beautiful fluidity from Ke Ma’s hands answered by the burning intensity of the cello. A dynamic drive to the treacherous second movement that they played with considerable mastery igniting passionate outcries of searing passion but always under control and with impeccable musicianship and mature mastery.They created a beautiful sense of discovery as the recitativo of the third movement evolved into the most passionate and fervent declamations between the two players.The last movement opening like a ray of sunshine after such a stormy journey was played with refreshing simplicity and quite considerable technical mastery with superb ensemble between these two very fine young players playing with exhilaration and excitement..

After such red hot passion ‘Ich liebe dich’ by Beethoven was played as an encore with simplicity and beauty and was an ideal antidote to such raging passions.

Born into an Irish family, cellist Finn Mannion grew up in the Scottish Highlands. He enjoys a richly varied musical life; a passionate chamber musician who is equally comfortable in concerto, duo and unaccompanied repertoire. A laureate of the Pablo Casals, Beatrice Huntington and Royal Philharmonic Society Isserlis Awards, Finn recently won First Prize at the 72nd Royal Over-Seas League Competition in London with his Trio Archai . He gave his Wigmore Hall debut in June 2024. Collaborating regularly with pianist Ke Ma, Finn is a Tunnell Trust award-winner and is on MakingMusic’s PDG-YoungArtist Scheme. He has been Associate Artist of the Aboyne Cello Festival since 2023. Performing extensively across the UK and Switzerland, Finn’s upcoming season will include recitals at St George’s Bristol, Hoylake Concert Society, Swiss Chamber Music Festival and Kelso Music Society to name a few. Born in 2002, Finn learnt with Ruth Beauchamp at St Mary’s Music School in Edinburgh before moving to Switzerland to study with German/Japanese cellist Danjulo Ishizaka at the Musik-Akademie Basel. He also studies Early Music with Petr Skalka at the Schola Cantorum Basilienis after formative lessons with David Watkin at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland. Finn is grateful for the continued mentorship of Celine Flamen and Gordan Nikolic, and for further cellist encounters with Steven Isserlis, Nicolas Altstaedt, Philip Higham, Bruno Delepelaire and John Myerscough. Finn plays a fine Italian cello by Giulio Cesare Gigli c. 1788, generously on loan from a private individual. Aside from music, Finn is an avid hillwalker, lover of dogs, and passionate street/portrait photographer.

Ke Ma studied at the Royal Academy of Music in London with Christopher Elton, Michael Dussek and Andrew West, graduating with a Masters with distinction (DipRAM) in 2017. She is currently pursuing her Doctoral study at Guildhall School of Music and Drama with Professor Joan Havill, Dr Alexander Soares and Rolf Hind. Ke has won top prizes at international competitions including 1st Prize at the 2016 Concours International de la vie de Maisons-Laffitte and Karoly Mocsari Special Prize (France), 1st Prize at the 2014 Shenzhen Competition (China) and 3rd Prize at the 2012 Ettlingen Competition (Germany). As a soloist, Ke made her debut at Wigmore Hall under the auspices of the Kirckman Concert Society, she has given concerts across the UK, Italy, France, Germany, Poland, Hungary and the US. Highlights have included appearances with the Tapiola Sinfonietta, Shenzhen Symphony Orchestra, Sichuan Symphony Orchestra, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Young Musicians Symphony, Suffolk Symphony Orchestra, Royal T unbridge Wells Symphony Orchestra, the Miskolc Symphony Orchestra conducted by Tamás Gál at the Palace of the Arts in Budapest. A committed chamber musician Ke has undertaken a Tunnell Trust Award tour of Scotland, given a recital at Wigmore Hall and recorded music by Vieuxtemps for Champs Hill Records with violist in Timothy Ridout. She has collaborated with cellist Margarita Balanas for The Royal Academy of Music ‘s Bicentenary Series recording. Since 2022, Ke and Finn have collaborated regularly.

Ke Ma at St Mary’s a seduction of luminosity and musicianship

The set of variations on the duet ‘Bei Männern, welche Liebe fühlen’ from Die Zauberflöte dates from 1801. Here the music is already laid out in such a way that the two instruments are in essence equal partners. It is especially delightful to follow the dialogue of the duet, with the piano in the role of Pamina and the cello answering it as Papageno.

Fantasiestücke op. 73, were written in 1849 and although they were originally intended for clarinet and piano, Schumann indicated that the clarinet part could be also performed on violin or cello.

Robert Schumann wrote the pieces over just two days in February 1849, and originally entitled them “Soirée Pieces” before settling on the title Fantasiestücke.

The three individual pieces are:

- Zart und mit Ausdruck (Tender and with expression)

- Lebhaft, leicht (Lively, light)

- Rasch und mit Feuer (Quick and with fire)

The A major Violin Sonata is one of César Franck’s best-known compositions, and is considered one of the finest sonatas for violin and piano ever written. After thorough historical study based on reliable documents, the Jules Delsart arrangement for cello (the piano part remains the same as in the violin sonata) was published by G.Henle Verlag as an Urtext edition. In his biography of Franck, Joël-Marie Fauquet reports on how there came to be a cello version. After a performance of the violin sonata in Paris on 27 December 1887, the cellist Jules Delsart, who was actively participating in this concert as a quartet player, was so enthusiastic that he begged Franck for permission to arrange the violin part for cello. In a letter that Franck wrote his cousin presumably only a little later, he mentioned: “Mr Delsart is now working on a cello arrangement of the sonata.” According to this, the arrangement for cello did not proceed from the publishing house, but from a musician who was a friend of the composer’s (both taught at the Paris Conservatoire). There is also no doubt about Franck’s consenting to this arrangement. Since the piano part remained unchanged, the renowned publishing house Hamelle did not publish the arrangement in an edition all its own (c. 1888), but simply enclosed the cello part with its separate plate number in the score.

The Violin Sonata in A was written in 1886, when Franck was 63, as a wedding present for the 28-year-old violinist Eugène Ysaŷe Twenty-eight years earlier, in 1858, Franck had promised a violin sonata for Cosima von Bulow . This never appeared; it has been speculated that whatever work Franck had done on that piece was put aside, and eventually ended up in the sonata he wrote for Ysaÿe in 1886. Franck was not present when Ysaÿe married, but on the morning of the wedding, on 26 September 1886 in Arlon, their mutual friend Charles Bordes presented the work as Franck’s gift to Ysaÿe and his bride Louise Bourdeau de Courtrai. After a hurried rehearsal, Ysaÿe and Bordes’ sister-in-law, the pianist Marie-Léontine Bordes-Pène played the Sonata to the other wedding guests.The Sonata was given its first public concert performance on 16 December of that year, at the Musée Moderne de Peinture in Brussels Ysaÿe and Bordes-Pène were again the performers. The Sonata was the final item in a long program which started at 3pm. When the time arrived for the Sonata, dusk had fallen and the gallery was bathed in gloom, but the museum authorities permitted no artificial light whatsoever. Initially, it seemed the Sonata would have to be abandoned, but Ysaÿe and Bordes-Pène decided to continue regardless. They had to play the last three movements from memory in virtual darkness. When the violinist Armand Parent remarked that Ysaÿe had played the first movement faster than the composer intended, Franck replied that Ysaÿe had made the right decision, saying “from now on there will be no other way to play it”.Vincent d’Indy , who was present, recorded these details of the event.His championing of the Sonata contributed to the public recognition of Franck as a major composer. This recognition was quite belated; Franck died within four years of the Sonata’s public première, and did not have his first unqualified public success until the last year of his life on 19 April 1890, at the Salle Pleyel , where his String Quartet in D was premiered.

During Franck’s lifetime the A major sonata was offered in two (more or less) equal variant settings (piano and violin; piano and cello), with the explicit reference to the arranger (Jules Delsart) of the cello version. César Franck probably had nothing against the title page in that he gave away appropriate copies to friends and acquaintances, including a dedication to the musicologist Adolf Sandberger.Comparing the two solo parts (violin vs. cello) demonstrates that Delsart kept very closely to the original and generally limited himself to transposing the violin part to the lower register. In only a few passages are there exceptions where Delsart adapted the music to the technical playing conditions of the cello.Delsart’s arrangement of Franck’s sonata for piano and cello has been one of the beloved sonatas in the instrument’s repertoire. With the publication of the Urtext edition by G.Henle Verlag in 2013, the integrity of the cello version is justified.(At the heart of G. Henle Verlag’s programme are the so-called Urtext Editions. They are characterized by their correct musical text, drawn up following strict scholarly principles, with an extensive commentary on the sources consulted – covering autographs, copies and early printings – and details regarding the readings.)

On the “oral and written history” that Cesar Franck first conceived the sonata for cello and piano (before the commission from Eugène Ysaŷe arrived), Pablo Casals wrote in 1968, “… what I remember distinctly is that Ysaÿe told me that Franck had told him that the Sonata was intended for violin or cello. That was the reason for my taking it up and playing it so much during my tours.”

Antoine Ysaÿe, Eugène Ysaÿe’s son, expressed in a letter that there is a version in César Franck’s handwriting for cello.