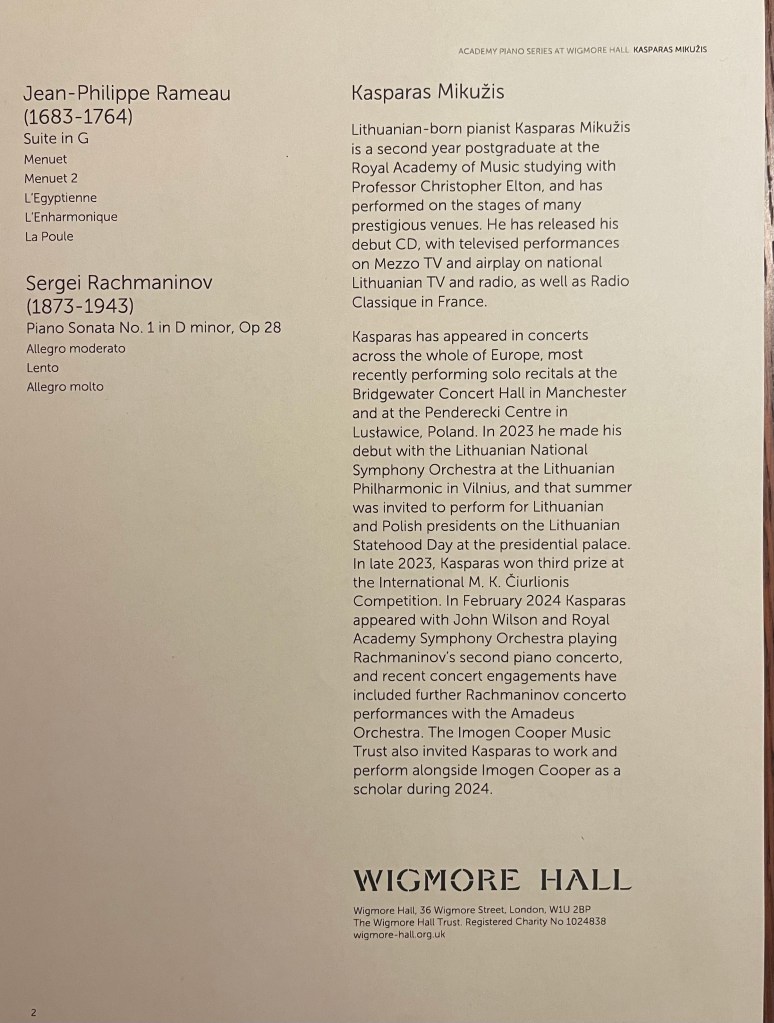

Promoted by the Royal Academy of Music.

Currently completing his postgraduate studies, the prize-winning Lithuanian pianist has been selected as a 2024 scholar of the Imogen Cooper Music Trust, as well as of the Countess of Munster Musical Trust and the Keyboard Trust. This programme features movements from Rameau’s Suite in G – including character pieces depicting ‘The Hen’, ‘The Enharmonic’ and ‘The Egyptian’ – alongside Rachmaninov’s First Piano Sonata, composed in 1908 in Dresden.

The triumph of the Lithuanians -Kasparas Mikužis ignites the Wigmore with the two ‘R’s’

There must be something in the air in Lithuania that allows their musicians to play with enviable fluidity and ravishing beauty.

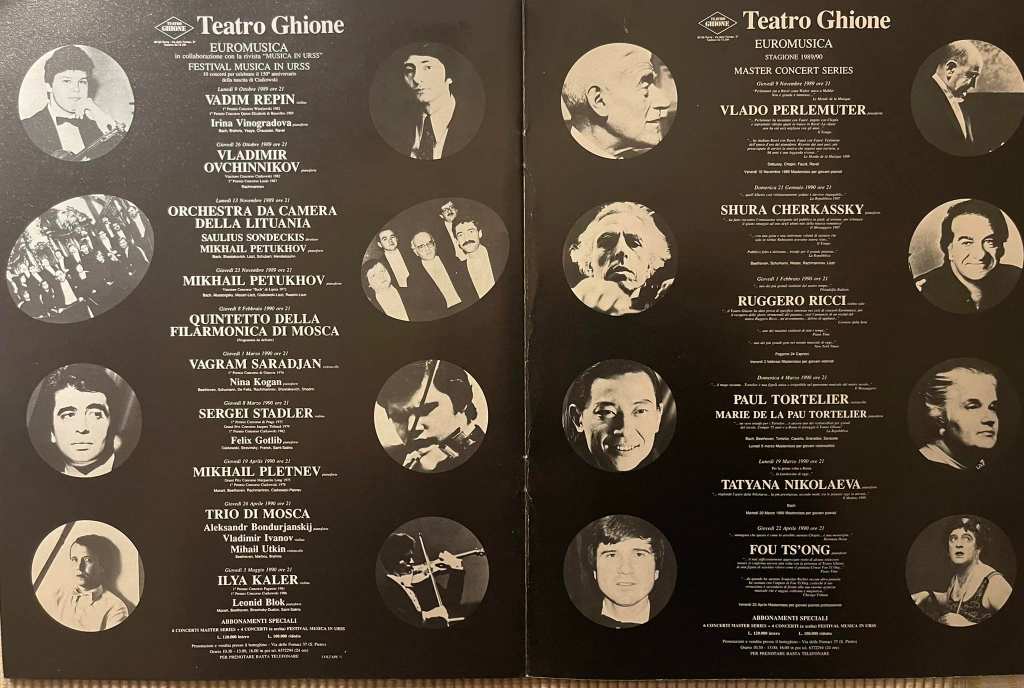

I remember many years ago in Rome with Saulius Sondeckis conducting the Lithuanian Chamber Orchestra playing unbelievably quietly and with such simplicity and fluidity.

It was the same that we heard today from the very first notes of Rameau with a wonderful flexibility and fluidity that the music seemed to just pour from the fingers of this extraordinary young musician .A minuet with ornaments that glistened like jewels contrasting with the profound utterings of ‘L’Egyptienne’ so elaborately embellished and played with poignant dignity and beauty .There followed a deeply poetic ‘L’Enharmonique’ before the delicious hypnotic rhythmic insistence of ‘La Poule.’

Nothing though could have prepared us for the explosion of ravishing sounds and passionate outpourings of Rachmaninov’s much troubled First Sonata.

Like Kantorow a few months ago on this very stage Kasparas has seen the secret path through this seeming labarinth of notes .The throbbing passion and innocent nostalgia together with the menace of the opening were the leit motifs of quite overwhelming authority and command.A performance for all those present ,including his teacher Christopher Elton, that will be placed on a pinnacle next to that of Kantorow restoring a masterpiece to it’s rightful place in the piano repertoire

Just five movements from Rameau’s suite of eight, beautifully chosen and placed in an order that made one unified whole.

The first minuet played with remarkable poise for a debut recital on such an important stage.

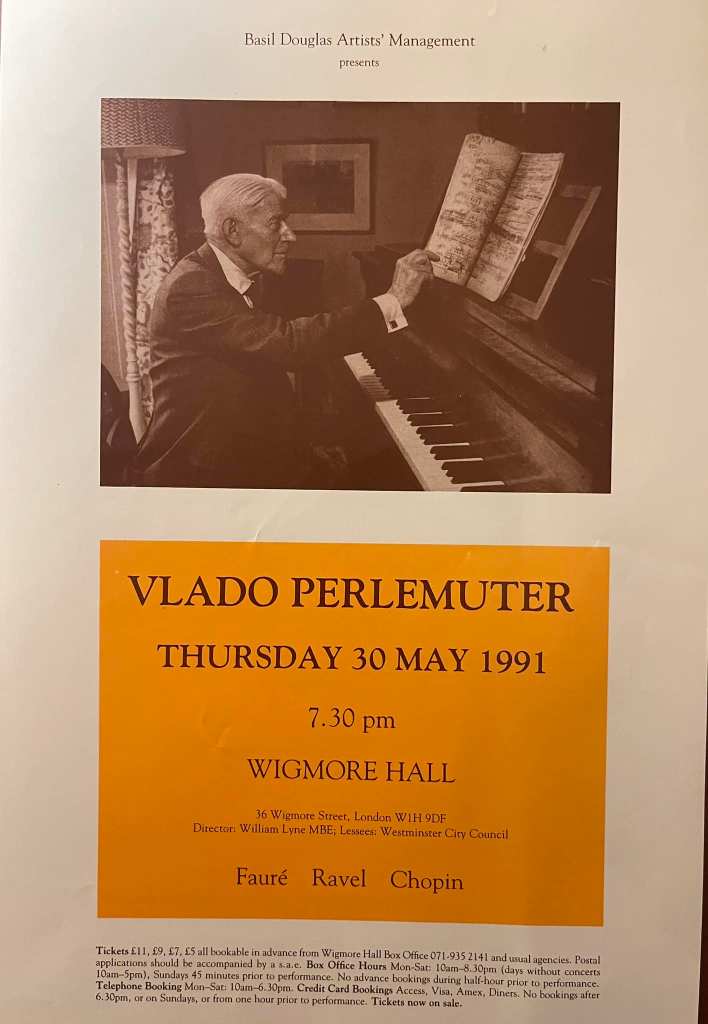

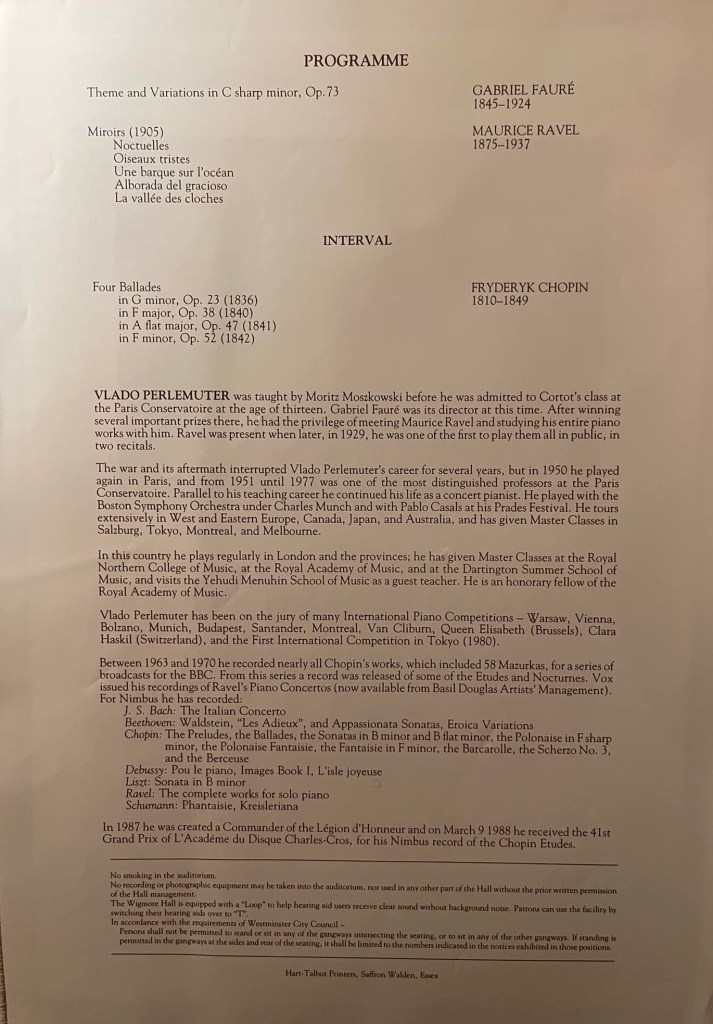

I remember Vlado Perlemuter telling me even at his last public performance aged 90 ,as I opened the door for him, he confided that every time those few steps were like going to the guillotine!

Kasparas too confided afterwards that for him ( as for all great artists), those few steps were the most difficult but that once he had summoned up the courage, the arrival at the piano was like being greeted by a great friend.

From the very first Minuet there was a lucidity and flexibility of natural stylish playing with ornaments like tightly wound springs . There was the continuous flowing sounds of the second minuet where the ornaments glistened like sparkling jewels .These contrasted with profound outpouring of the elaborately embellished ‘L’Egyptienne’ played with poignant dignity and beauty.Paired with ‘L’Enharmonique’ that was deeply poetic .’La Poule’ burst onto the scene with a radiant glowing insistence with some ravishing contrasted layers of sound and hypnotic characterisation.

A short break and a long pause of reflection before Kasparas embarked on his long voyage of discovery with Rachmaninov’s First Sonata. The second sonata had enjoyed a revival since Horowitz presented it in one of his recitals during his long Indian summer.Since then there is rarely a season where it does not figure on recital programmes. The first has fared less well and it is enough to say that even Rachmaninov found it a difficult work to compose.Taking standard forms but like the Liszt Sonata or Schubert Wanderer giving the main motifs a life of their own as they are transformed during a long voyage almost as if there was a great story unfolding.

Ogdon was one of the first to bring it to light but was more of an intellectual performance of a pianistic genius than creating a platform for dramatic story telling of menace,exhilaration and reconciliation.It was Kantorow in his historic Philharmonie recital that suddenly shone a light on a misunderstood masterpiece.Since that performance it has now almost taken the place of the second in conservatories,competitions and concert halls.

Lukas Genusias recently found the original manuscript with changes that the composer was later to make as with his 1913 and 1931 versions of the second sonata. Horowitz was to make his own version of the second from both versions , sanctioned by his friend Rachmaninov who was plagued with depression and doubts.

I think the newly found original score closely resembles the final published one that Kasparas played today but I would be very interested to see changes made by the composer as he did with many works that were not immediately of the success of his more popular scores.

Kasparas brought streams of golden sounds and a pulsating passion from the very opening. A frightening amount of notes that are infact streams of sounds after the opening menace of the first notes deep in the bass.The third motif is a wonderful fluid melody of heartbreaking nostalgia and warming reconciliation that between the menace and the pulsating hypnotic insistence of a single note that is like a heartbeat naked for all to see. A passionate climax of overwhelming emotion was played with transcendental mastery as it died to a mere whisper with a gentle drooping tear barely whispered in our ear .Kasparas painted a canvas of such unconcealed emotion and passion that this might well be given an X certificate on it’s next appearance ! An etherial opening to the ‘Lento’, building in emotional beauty with a ravishing sense of balance .The melodic line rose like an eagle of radiant beauty above the seething cauldron of ever more intense sounds .There was a timeless beauty to the ending where the magic wand of this young musician had cast his spell on a thankfully large audience.

This was short lived as the ‘Allegro molto’ exploded with supersonic energy and astonishing mastery. Bursting into a rhythmic march of exhilaration and breathtaking daring .Rachmaninov’s melodic line coming through a maze of sounds like a knight in shining armour with glorious romantic abandon and with our Prince leading the way with fearless authority. Here the reappearance of the theme of reconciliation was one of those magic moments, all too rare in this mechanical age , when a group of unknown people are suddenly united in a joint experience of emotional beauty .A miracle and one that this young Lithuanian performed with mastery and humility.

The final tumultuous awakening was quite overwhelming and was greeted with rapturous applause by those that had been fortunate enough to share in such an experience .

A simple little piece by a compatriot composer was Kasparas’s way of thanking us.

Kasparas Mikuzis the outsider takes St Mary’s by storm

Rachmaninov’s First in D minor op 28 was completed in 1908.It is the first of three “Dresden pieces”, along with the symphony n.2 and part of an opera, which were composed in the quiet city of Dresden.It was originally inspired by Goethe’s tragic play Faust,although Rachmaninoff abandoned the idea soon after beginning composition, traces of this influence can still be found.After numerous revisions and substantial cuts made at the advice of his colleagues, he completed it on April 11, 1908. Konstantin Igumnov gave the premiere in Moscow on October 17, 1908. It received a lukewarm response there, and remains one of the least performed of Rachmaninoff’s works.He wrote from Dresden, “We live here like hermits: we see nobody, we know nobody, and we go nowhere. I work a great deal,”but even without distraction he had considerable difficulty in composing his first piano sonata, especially concerning its form.Rachmaninoff enlisted the help of Nikita Morozov , one of his classmates from Anton Arensky’s class back in the Moscow Conservatory, to discuss how the sonata rondo form applied to his sprawling work.Rachmaninov performed in 1907 an early version of the sonata to contemporaries including Medtner.With their input, he shortened the original 45-minute-long piece to around 35 minutes and completed the work on April 11, 1908. Igumnov gave the premiere of the sonata on October 17, 1908, in Moscow.

Lukas Geniusas writes about his premiere recording of the Rachmaninov Sonata n. 1 to be issued in October : ‘About a year ago I came across a very rare manuscript of the Rachmaninov’s Sonata no.1 in its first, unabridged version. It had never been publicly performed.

This version of Sonata is not significantly longer (maybe 3 or 4 minutes, still to be checked upon performing), first movement’s form is modified and it is also substantially reworked in terms of textures and voicings, as well as there are few later-to-be-omitted episodes. The fact that this manuscript had to rest unattended for so many years is very perplexing to me. It’s original form is very appealing in it’s authentic full-blooded thickness, the truly Rachmaninovian long compositional breath. I find the very fact of it’s existence worth public attention, let alone it’s musical importance. Pianistic world knows and distinguishes the fact that there are two versions of his Piano Sonata no.2 but to a great mystery there had never been the same with Sonata no.1.’

Sergei Rachmaninov (1873–1943)

Piano Sonata No. 1 in D Minor Op. 28 (1907)

Allegro moderato

Lento

Allegro molto

Rachmaninoff wrote to his friend Nikita Morozov on 8 May 1907:

‘The Sonata is without any doubt wild and endlessly long. I think about 45 minutes. I was drawn into such dimensions by a programme or rather by some leading idea. It is three contrasting characters from a work of world literature. Of course, no programme will be given to the public, although I am beginning to think that if I were to reveal the programme, the Sonata would become much more comprehensible. No one will ever play this composition because of its difficulty and length but also, and maybe more importantly, because of its dubious musical merit. At some point I thought to re-work this Sonata into a symphony, but that proved to be impossible due to the purely pianistic nature of writing’.

It is said that Rachmaninoff withdrew this reference to literature and certainly the music contains other associations.

The ‘literature’ he referred to is Goethe’s Faust (possibly with elements of Lord Byron’s Manfred) and there is convincing evidence to believe that this plan to write a sonata around Faust, Gretchen and Mephistopheles was never entirely abandoned. of course there are other musical elements present as it is not programme music. The pianist Konstantin Igumnov, who gave its premiere performance in Moscow, Leipzig and Berlin, visited Rachmaninoff in November 1908 after the Leipzig recital, the composer told him that ‘when composing it, he had in mind Goethe’s “Faust” and that the 1st movement related to Faust, the 2nd one to Gretchen and the 3rd was the flight to the Brocken and Mephistopheles.’

Faust in the opening monologue of the play:

In me there are two souls, alas, and their

Division tears my life in two.

One loves the world, it clutches her, it binds

Itself to her, clinging with furious lust;

The other longs to soar beyond the dust

Into the realm of high ancestral minds.

A man whose soul is rent between the hedonistic pleasures of the earth and spiritual aspirations – Sacrum et Profanum. Exploring this all to human dichotomy, Rachmaninoff builds almost unbearable tension.

In the Allegro moderato as Faust wrestles with his soul and temptations. Kantorow constructed and extraordinary edifice of unique sound, each note of each the massive chord weighted perfectly against the others to create a richness of great magnificence and splendour, rather like an organ His tone is liquid gold and even in passages of immense dynamic power he did not break the sound ceiling of the instrument. There was superb delicacy here. The delineation of eloquent melody and the dense polyphony of Rachmaninoff’s writing was miraculously transparent.

The Lento second movement could well be interpreted as a lyrical poem expressing the love of Gretchen for Faust. Kantorow was so poetic here yet managing the dense polyphony once again with great artistry, tenderness and delicacy. His melodic understanding was paramount. The legato cantabile tone was sublime, the execution carrying with it an uncanny feeling of lyrical improvisation. A fervent and impassioned love song…

The wildness of the immense final movement Allegro molto with its references to a terrifying Dies Irae and death can well associate this massive declamation to Mephistopheles and insidious and destructive evil. Kantorow built a Chartres Cathedral of sound here with immense structural walls embroidered with the most delicate of decoration relieved by moments of refined reflection. Are we exploring the darker significance of Walpurgis Night? Kantarow extracted and expressed a diabolism seldom encountered in any piano recital. All my remarks are assuming his towering technical ability and nervous pianistic concentration of a remarkable kind. Overwhelming.

Walpurgisnacht Kreling: Goethe’s Faust. X. Walpurgisnacht, 1874 – 77

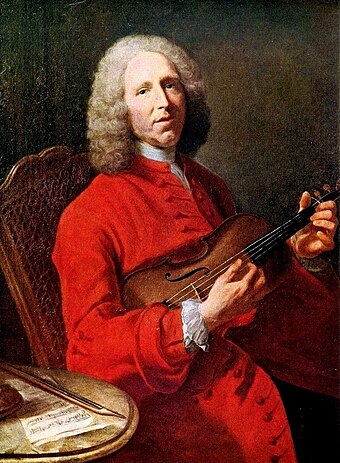

The French Baroque composer Jean-Philippe Rameau wrote three books of Pièces de clavecin for the harpsichord. The first, Premier Livre de Pièces de Clavecin, was published in 1706; the second, Pièces de Clavecin, in 1724 ;and the third, Nouvelles Suites de Pièces de Clavecin, in 1726 or 1727. They were followed in 1741 by Pièces de clavecin en concerts, in which the harpsichord can either be accompanied by violin (or flute) and viola da gamba or played alone. An isolated piece, “La Dauphine“, survives from 1747.

The exact date of publication, at Rameau’s own expense, of the Nouvelles Suites de Pièces de Clavecin remains a matter of some controversy. In his 1958 edition of the works, the editor Erwin Jacobi gave 1728 as the original publication date. Kenneth Gilbert, in his 1979 edition, followed suit. Others later argued that these works did not appear until 1729 or 1730. However, a recent reexamination of the publication date, based on the residence Rameau provided in the frontispiece (Rue des deux boules aux Trois Rois), suggests an earlier date, since Rameau’s residence had changed by 1728. As a result of this and other evidence, the closest approximation for the original publication date stands between February 1726 and the summer of 1727. This dating is given further authentication by the comments of Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg, who provided their publication date as 1726. There are almost 40 extant copies of the original 1726/27 edition.

Two later editions followed both around 1760. The first (printed perhaps slightly before 1760) was simply a reimpression of the original engravings, although several plates were reengravings, suggesting that the original plates had undergone sufficient impression to wear them down to a state of illegibility. A second appeared in London under the title A Collection of Lessons for the harpsichordfrom the printer John Walsh which was based on the earlier Parisian edition.Suite in G major/G minor, RCT 6

- Les Tricotets. Rondeau

- L’indifférente

- Menuet I – Menuet II

- La Poule

- Les Triolets

- Les Sauvages

- L’Enharmonique. Gracieusement.

- L’Égyptienne

c. 23 mins