Tyler Hay by candlelight with two Chopin recitals in one evening in the 1901 Club in Waterloo.

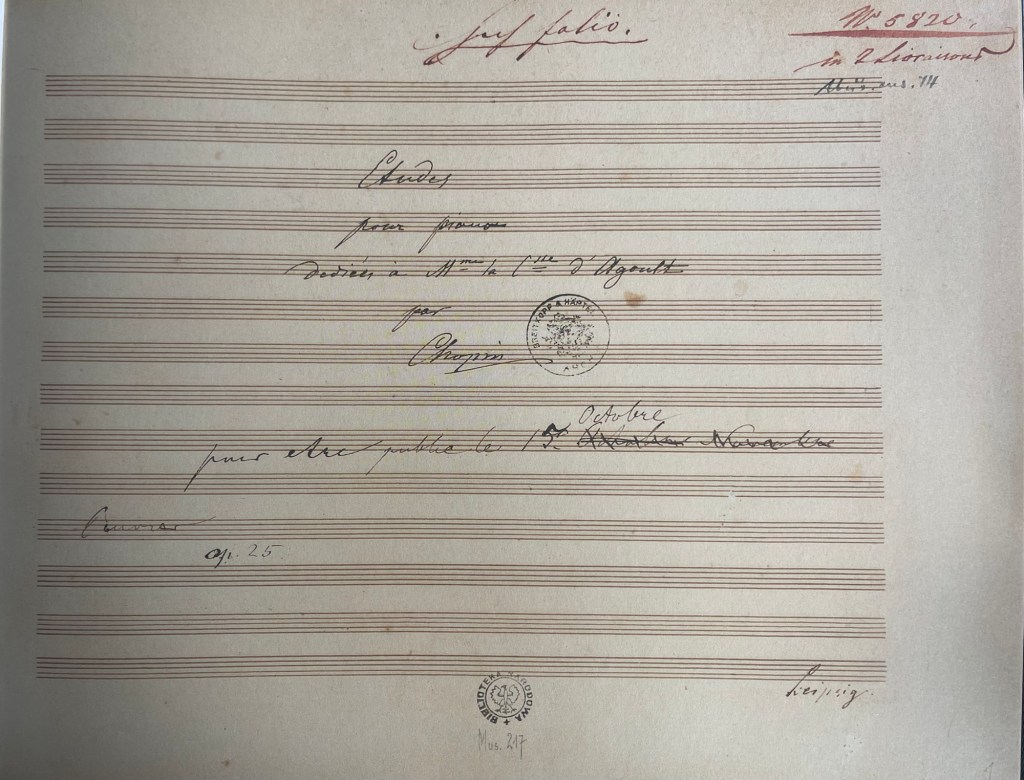

A programme that included the Etudes op 25 and the B flat minor Sonata op 35.

Having played 24 studies by Czerny for his birthday treat in Perivale and the Alkan Symphony for Thomas Kelly’s Piano festival I think the amount of notes that this young man has managed to digest this month must go down in the Guinness book of records.

Tyler Hay at St Mary’s Perivale ‘The Perfect Pianist comes of age ‘

Leaving his 20’s behind him with a bang as he enters maturity and demonstrates his artistic integrity and capacity with a smile on his face which defies the serious musician behind this glittering facade.Delving deep into the scores as he not only searches in the archives finding some true lost gems but also discovering details in well known scores that have been inexplicably overlooked.

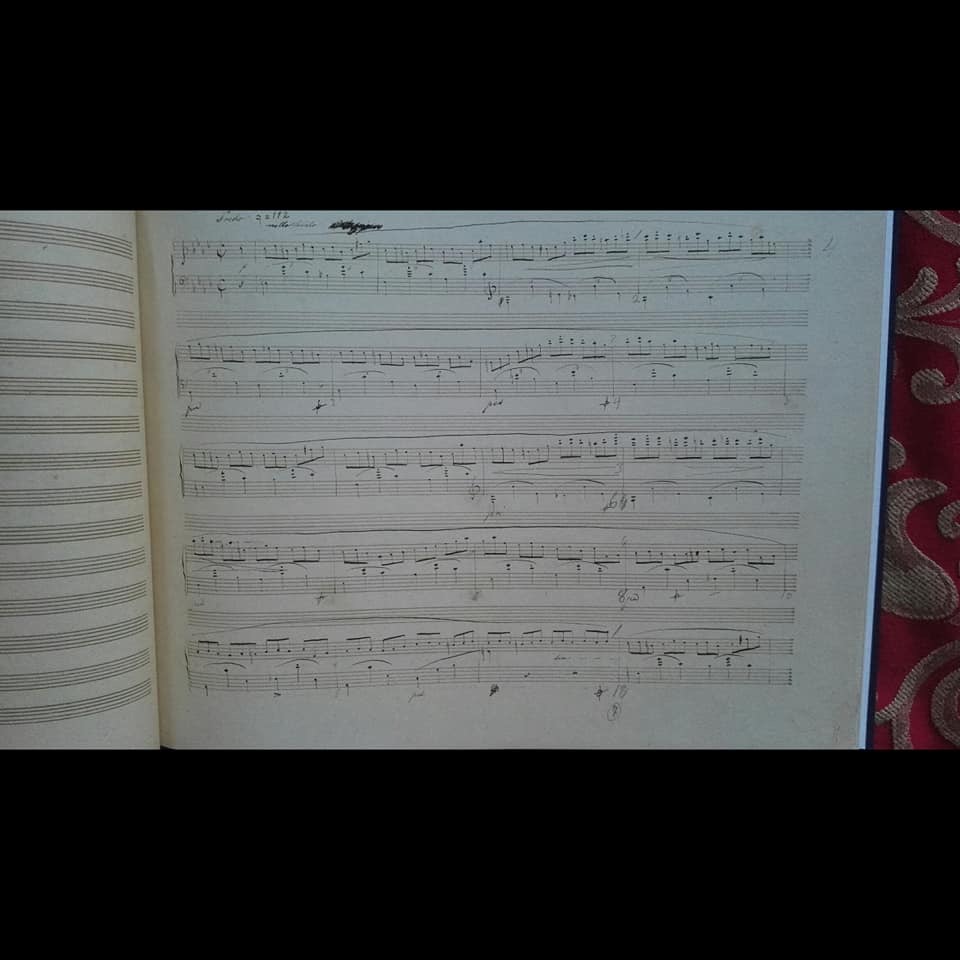

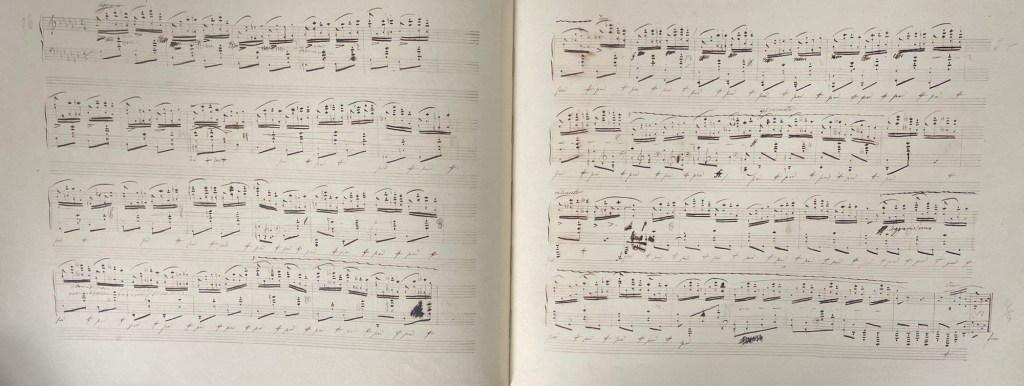

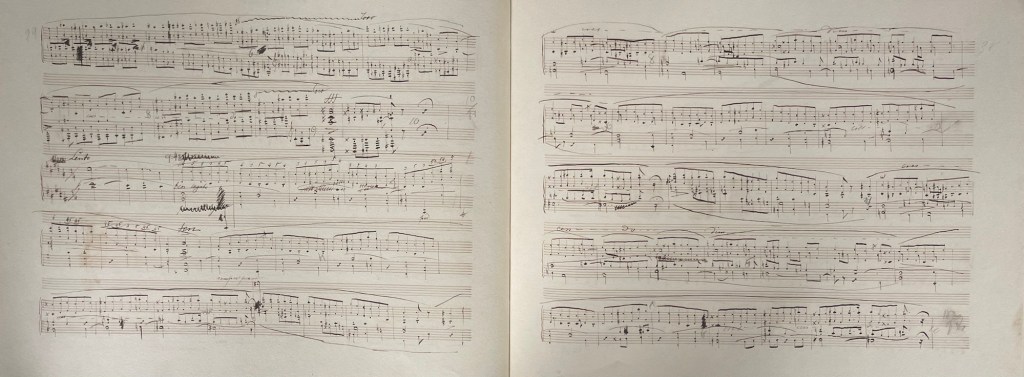

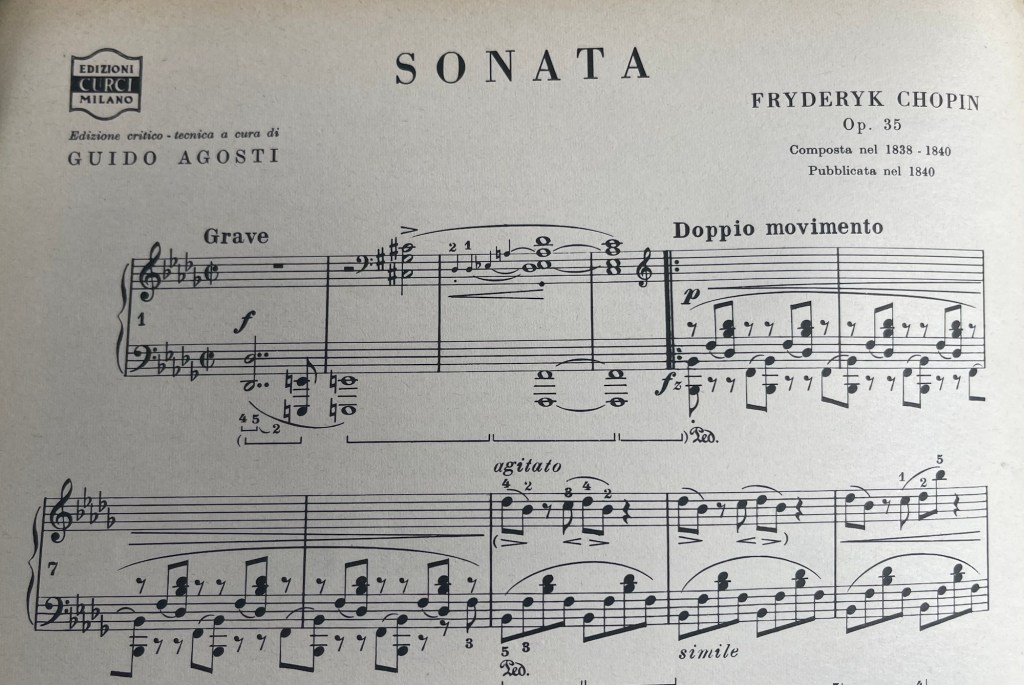

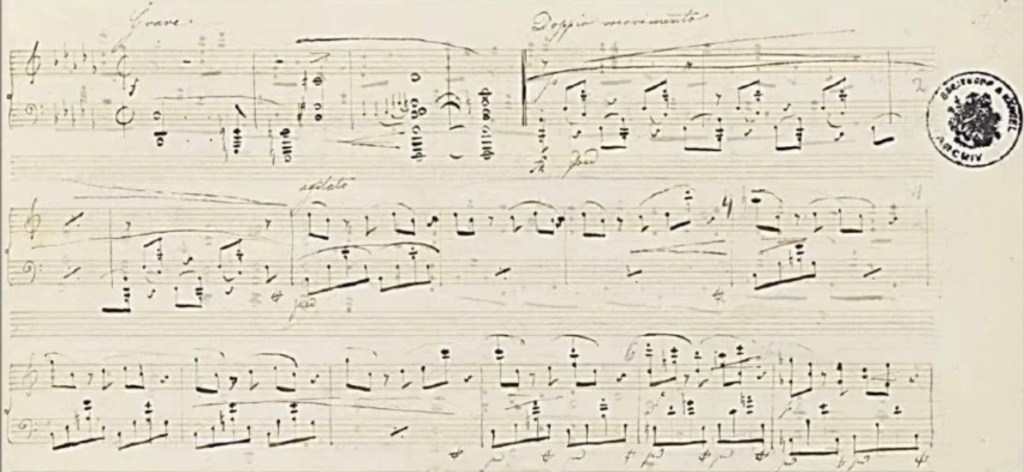

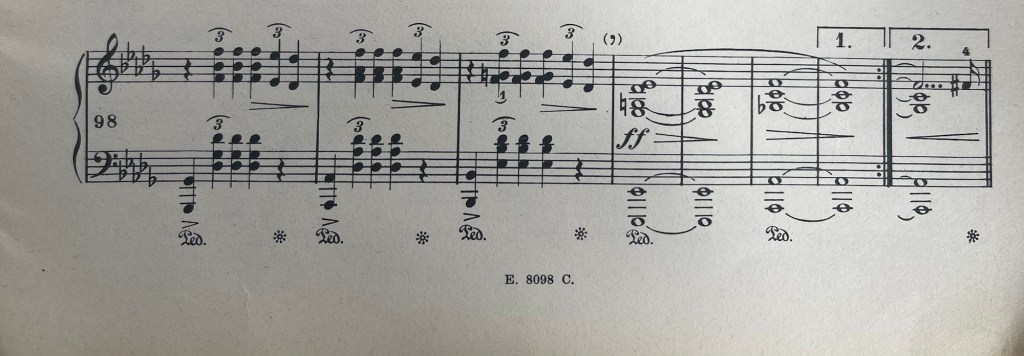

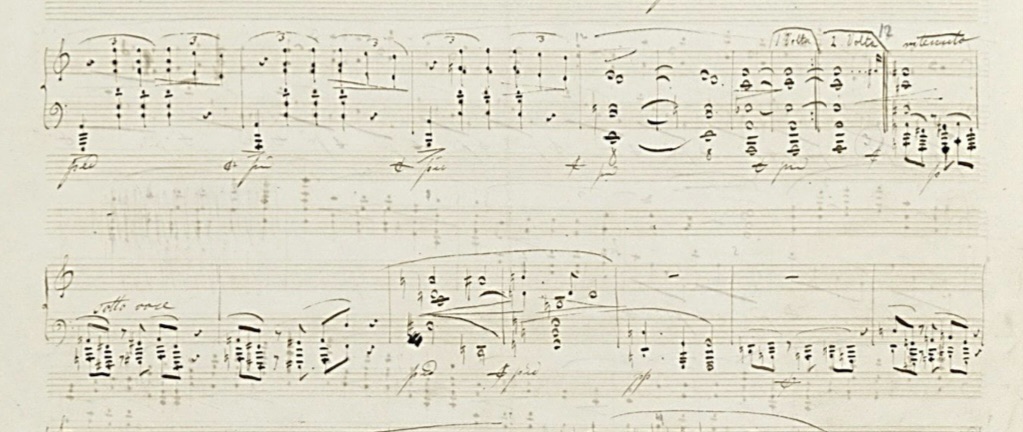

Just such a case in point was outlined by Tyler when I innocently asked him the 100 dollar question.What do you do about the repeat in the first movement of the Chopin B flat minor Sonata ? Tyler had looked very carefully at the manuscript score and found that the bass octave A flat is not tied but repeated and would take us very naturally back to the opening D flat and so to the ‘Grave’ not to the ‘doppio movimento’ which is the root of much conjecture! A detail for sure but for discerning interpreters it is essential to search out all the deciphers that the composers have left for posterity.I am of the opinion of Rubinstein that it is better not to repeat the exposition as was the traditional manner of all classical Sonatas.I also think the same is true of the Schubert Sonatas written around the same time as Chopin’s.These were two composer using the traditional forms still that were soon to change thanks to Schubert’s Wanderer Fantasy taken up by Liszt incorporating the transformation of themes as a new art form.

However Tyler gave an exemplary performance and it was particularly fresh and simple without any rhetoric from the so called Chopin tradition but playing exactly what he found in the score with musicianship and mastery.It was Schnabel who famously said ( about Mozart but it certainly could apply to Chopin too ) that ‘ music is too difficult for adults but too easy for children!’ There was an overall architectural shape to the first movement where the second subject was ‘sostenuto’ ( with more weight) rather than at a different tempo.It allowed the music to flow naturally and carried us along on a wave of sublime inspiration.There was precision in the Scherzo but also a feeling of buoyancy that allowed the Trio to be a complete contrast and only a slight relaxation of tempo as Chopin indicates ‘piu lento’.A Funeral March of poignancy and beauty was followed by the whispering of ‘the wind over the gravestones’ or as Schumann said ‘more of a mockery than any sort of music’.Little could we have imagined the struggle that Tyler had on the hottest day of the the year to navigate such folly with the keys bathed in water!

In fact Tyler had chosen to finish the recital in true aquatic fashion with a Venetian Boat Song op 19 n.6 by Mendelssohn a composer that Tyler impishly said that Chopin hated !

Luckily the next work was the Nocturne op 72 n.4 that Tyler had learnt but had not actually programmed in his recitals.So this was the ideal occasion before embarking of twelve of the most strenuous pieces for piano ever written!

And so it was today that we heard the Chopin Studies op 25 played as the composer had indicated.Each of the 12 studies was a miniature tone poem.Bathed in the sunlight, or should I say candlelight,that Chopin’s own pedal indications had asked for .Tyler shaped each one with a luminosity and poetry that I have only heard similar on the old recording of Cortot. Completely different of course but the one thing- the most important thing in common was the poetry that is concealed in what are conceived also as studies.

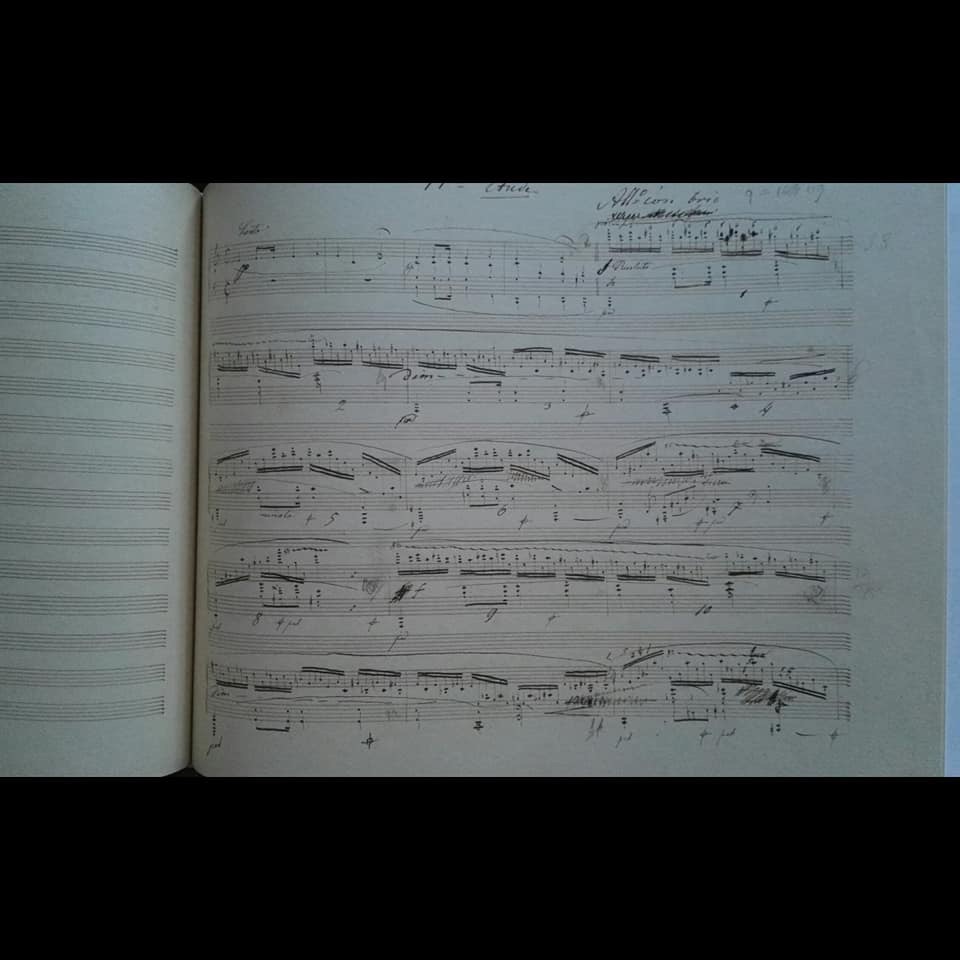

The Aolian Harp of the first study showing exactly what Sir Charles Hallé had described on hearing Chopin on his last tour in Manchester.

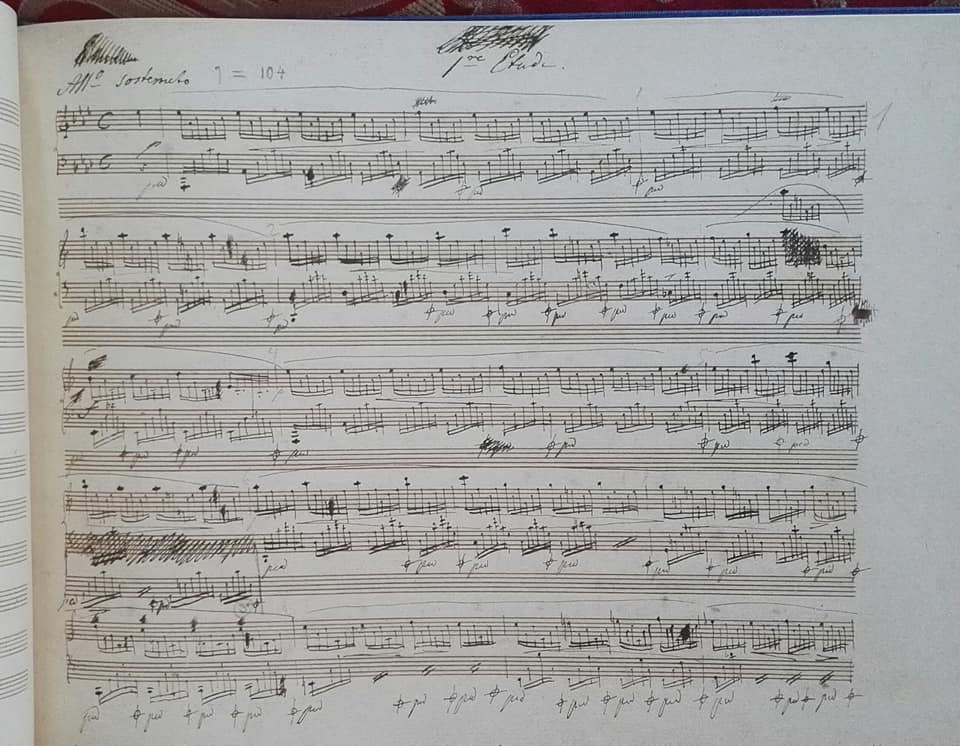

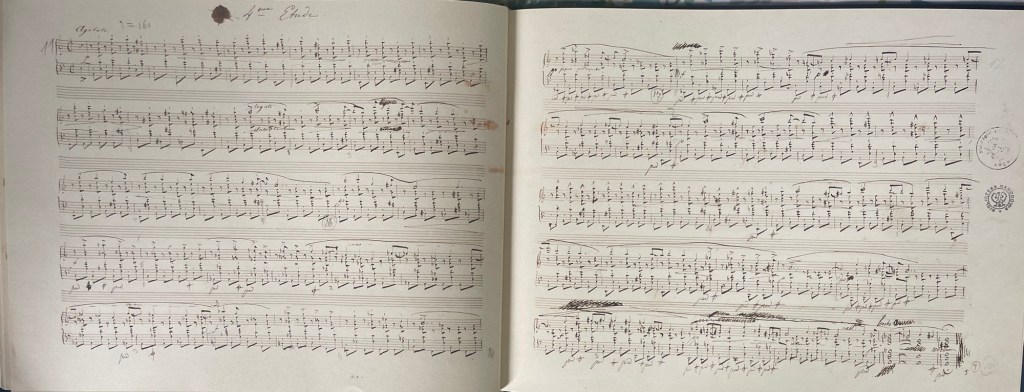

”Il faut graver bien distintemente les grandes e les petites notes” writes Chopin at the bottom of the first page .Long pedal markings overlapping the bar lines and the pianissimo asked for by Chopin so perfectly played by Tyler. The long held pedal at the end gave such an etherial magical sound.

The second study too like silk.Not the usual note for note performances we are used to but washes of sound perfectly articulated of course but with the poetry and music utmost in mind.The final three long “C’s” which can sound out of place were here of a magic that one never wanted them to stop.It was interesting to note that Rubinstein played this study,which I had never heard before in his recitals,at the last concert in his long career at the Wigmore hall in 1976.

The third and fourth to contrast were played with great clarity with some suprising inner notes that gave such substance and depth to the sound.The end of the fifth that linked up to the 6th.It grew out of the final crescendo flourish that always had seemed out of place .Here in Tyler’s hands it is exactly as Chopin in his own hand has indicated.

Here too one must mention the sumptuous middle melody of the fifth played with a wonderful sense of balance and also a flexibility of pulse that again showed the hands of a great musical personality.I have only heard a similar sense of “rubato” live from Rubinstein although Murray Perahia on CD is pure magic too.

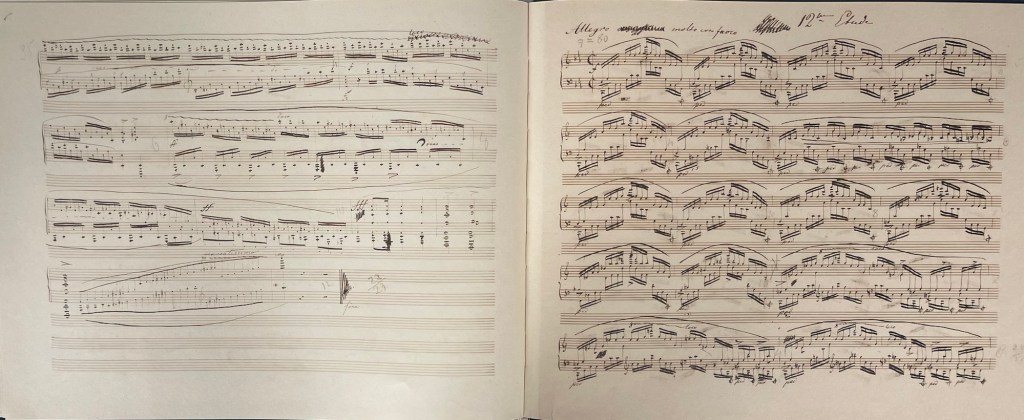

The technically difficult double thirds accompanied the left hand melodic line with a subtle sense of sound like a wind passing over the grave indeed !The absolute clarity and jeux perlé of the “double” thirds was just the relief and contrast that was needed.

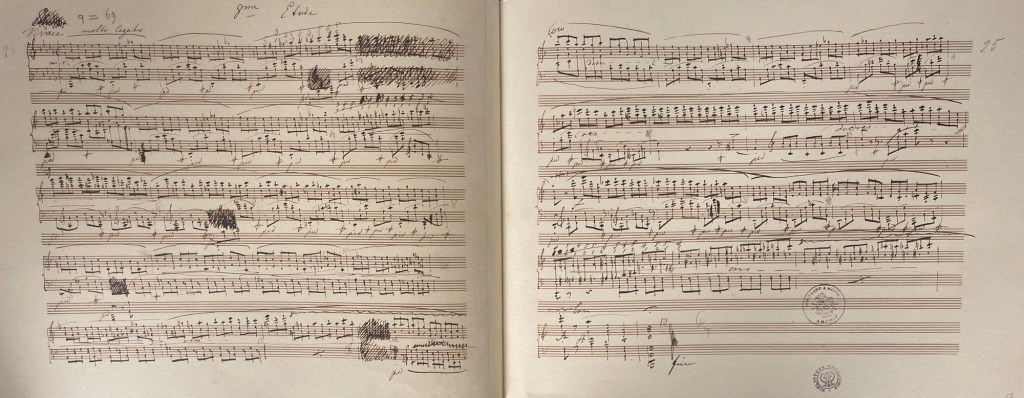

Beautiful sense of colour in the Lento that is the 7th study where Chopin marks so clearly that the melody is in the left hand with only counterpoint comments from the right( Cortot and Perlemuter are the only others that I have heard make this distinction so clearly)

The 8th played very much molto legato and sotto voce to contrast with the absolute clarity of the “ Butterfly” study that is n.9.The ending that can sound so abrupt in some hands here was perfectly and so naturally shaped.

The great octave study entered like a mist as Chopin indicates poco a poco crescendo .

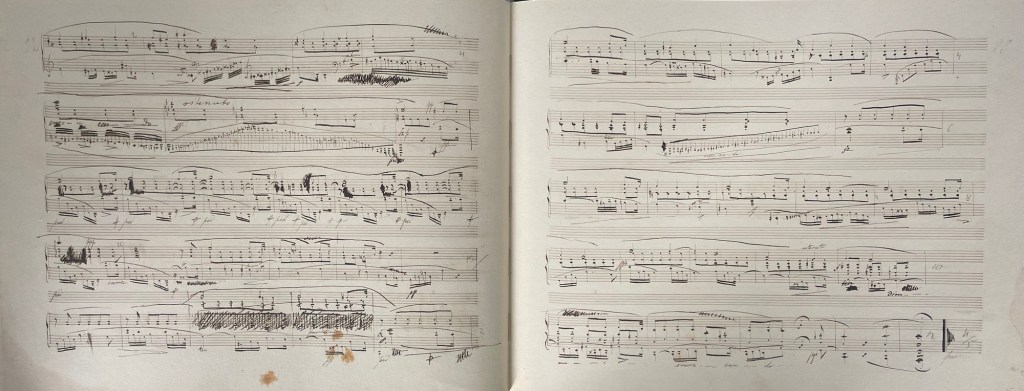

Such was his identification with this sound world he had seen this study as great wedges of sound interrupted only by the extreme legato cantabile of the middle Lento section. Chopin marks very precisely here the fingering he wants to obtain this effect.

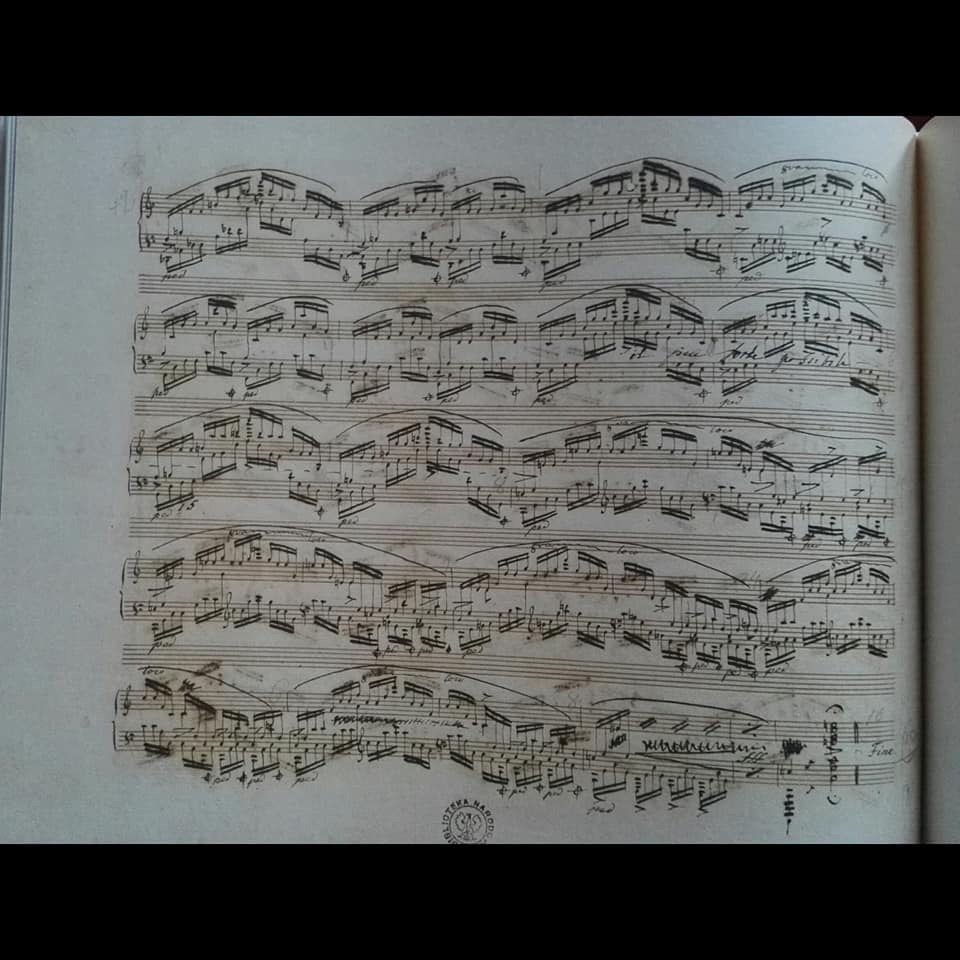

The great “Winter Wind” study n. 11 where there were great washes of sound ,again as Chopin so clearly indicates .The final great scale played unusually cleanly with a very precise final note.Of course all clearly indicated in Chopin’s own hand .

The final 12th study was played with enormous sonority and very clear melodic line as Chopin indicates very clearly .The ending marked “ il piu forte possibile” and a final crescendo to “fff”. It brought this revelatory performance to a breathtaking ending.

Fryderyk Franciszek Chopin 1 March 1810 Zelazowa Wola, Poland

17 October 1849 (aged 39). Paris, France

Some time after writing the Marche funèbre,(1837) Chopin composed the other movements of the Sonata op 35 ,completing the entire sonata by 1839. In a letter on 8 August 1839, addressed to Fontana, Chopin wrote:

I am writing here a Sonata in B flat minor which will contain my March which you already know. There is an Allegro, then a Scherzo in E flat minor, the March and a short Finale about three pages of my manuscript-paper. The left hand and the right hand gossip in unison after the March. … My father has written to say that my old sonata [in C minor, Op. 4] has been published by Haslinger and that the German critics praise it. Including the ones in your hands I now have six manuscripts. I’ll see the publishers damned before they get them for nothing.

Haslinger’s unauthorised dissemination of Chopin’s early C minor sonata (he had gone as far as engraving the work and allowing it to circulate, against the composer’s wishes) may have increased the pressure Chopin had to publish a piano sonata, which may explain why Chopin added the other movements to the Marche funèbre to produce a sonata.It was finished in the summer of 1839 in Nohant in France and published in May 1840 in London,Leipzig and Paris.

‘Chopin is still up and down, never exactly good or bad. […] He is gay as soon as he feels a little strength, and when he’s melancholy he falls back onto his piano and composes beautiful pages.’

(Letter from George Sand to Charlotte Marliani, end of July 1839)

‘His creativity was spontaneous, miraculous’, wrote Sand in The Story of My Life,‘he found it without seeking it, without expecting it. It arrived at his piano suddenly, completely, sublimely, or it sang in his head during a walk, and he would hasten to hear it again by recreating it on his instrument………..But then would begin the most heartbreaking labour I have ever witnessed…….He would shut himself up in his room for days at a time, weeping, pacing, breaking his pens, repeating or changing a single measure a hundred times, writing it and erasing it with equal frequency and beginning again the next day with desperate perseverance. He would spend six weeks on a page, only to end up writing it just as he had done in his first outpouring.’

The sonata comprises four movements:

- Grave – Doppio movimento

- Scherzo

- Marche funèbre: Lento

- Finale: Presto

The first major criticism, by Schumann , appeared in 1841. He described the sonata as “four of [his] maddest children under the same roof” and found the title “Sonata” capricious and slightly presumptuous.He also remarked that the Marche funèbre “has something repulsive” about it, and that “an adagio in its place, perhaps in D-flat, would have had a far more beautiful effect”.In addition, the finale caused a stir among Schumann and other musicians. Schumann said that the movement “seems more like a mockery than any [sort of] music”,and when Felix Mendelssohn was asked for an opinion of it, he commented, “Oh, I abhor it”. Franz Liszt, a friend of Chopin’s, remarked that the Marche funèbre is “of such penetrating sweetness that we can scarcely deem it of this earth”.It was Anton Rubinstein who said that the fourth movement is the “wind howling around the gravestones”.

When the sonata was published in 1840 the London and Paris editions indicated the repeat of the exposition as starting at the very beginning of the movement (at the Grave section). However, the Leipzig edition designed the repeat as beginning at the Doppio movimento section. Although the critical edition published by Breitkopf & Hartel (that was edited, among others, by Franz Liszt, Carl Reinecke , and Johannes Brahms ) indicate the repeat similarly to the London and Paris first editions, almost all 20th-century editions are similar to the Leipzig edition in this regard with the repeat to the Doppio movimento ,Charles Rosen argues that the repeat of the exposition in the manner perpetrated by the Leipzig edition is a serious error, saying it is “musically impossible” as it interrupts the D♭ major cadence (which ends the exposition) with the B♭ minor accompanimental figure.Karol Mikuli’s 1880 complete edition of Chopin contained a repeat sign after the Grave in the first movement of the Piano Sonata No. 2. Mikuli was a student of Chopin from 1844 to 1848 and also observed lessons Chopin gave to other students – including those where this sonata was taught – and took extensive notes.

Many great artists including Barenboim,Horowitz,Rachmaninoff,Rubinstein,Ohlssohn,Kissin exclude the repetition altogether