Bruce Liu piano

Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) Piano Sonata in B minor HXVI/32 (by 1776)

I. Allegro moderato • II. Menuet • III. Finale.

Presto

Fryderyk Chopin (1810-1849) Piano Sonata No. 2 in B flat minor Op. 35

‘Funeral March’ (1837-9)

I. Grave – Doppio movimento • II. Scherzo •

III. Marche funèbre • IV. Finale. Presto

Interval

Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683-1764) Les tendres plaintes (pub. 1724)

Les cyclopes (pub. 1724)

Menuet I and II (c.1729-30)

Les sauvages (c.1729-30)

La poule (c.1729-30)

Gavotte et 6 doubles (c.1729-30)

Fryderyk Chopin Variations on ‘Là ci darem la mano’ Op. 2 (1827)

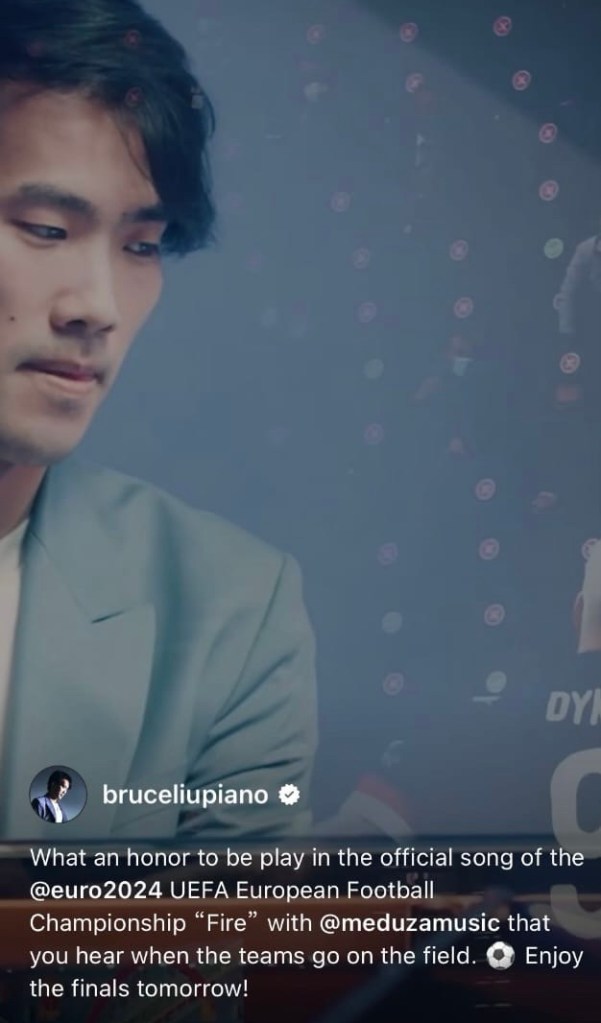

Bruce Xiao Liu kicking off in London while the whole world is watching the kick off in Berlin .

I have no idea how the players are getting on but I do know that from the very first notes of the Haydn B minor Sonata Bruce created the same magic of the greatest musicians from a past age that are now just posters in the green room of a golden age.

It was Jed Distler ,the New York correspondent for the Chopin competition,who had immediately noticed this young man for his sense of colour and style in the Chopin Rondo op 2 .The one that Schumann on hearing Chopin play wrote :’Hats off gentlemen a Genius’.

The ravishing jewel like precision of the opening Allegro moderato of Haydn was with a delicacy and range of colours but always a great sense of style and elegant good taste .There was dynamic drive and superb clarity of a jeux perlé that was beguiling and mesmerising .Such crystalline clarity and beauty of shading that the only word to describe it , is exquisite. But not of a porcelain doll but of a passionate vibrancy of great daring and intelligence .

A Menuet that was a true jewel box of delicacy and a trio of passionate persuasion

A presto Finale that was of lightweight etherial brilliance with a ‘joie de vivre’ of scintillating impish good spirits .

The noblest of ‘Grave’ introductions to the Chopin B flat minor Sonata was that of a true storyteller who had something wondrous to share .A Chopin of aristocratic nobility and architectural shape and with a continual forward movement of passionate conviction. A relentless ‘doppio movimento’ that at times might have seemed too driven until one arrived at the sumptuous outpouring of the second subject.No worries about the much discussed repeat that Bruce had no time to even consider as he had seen this movement as a flowering of genial invention.

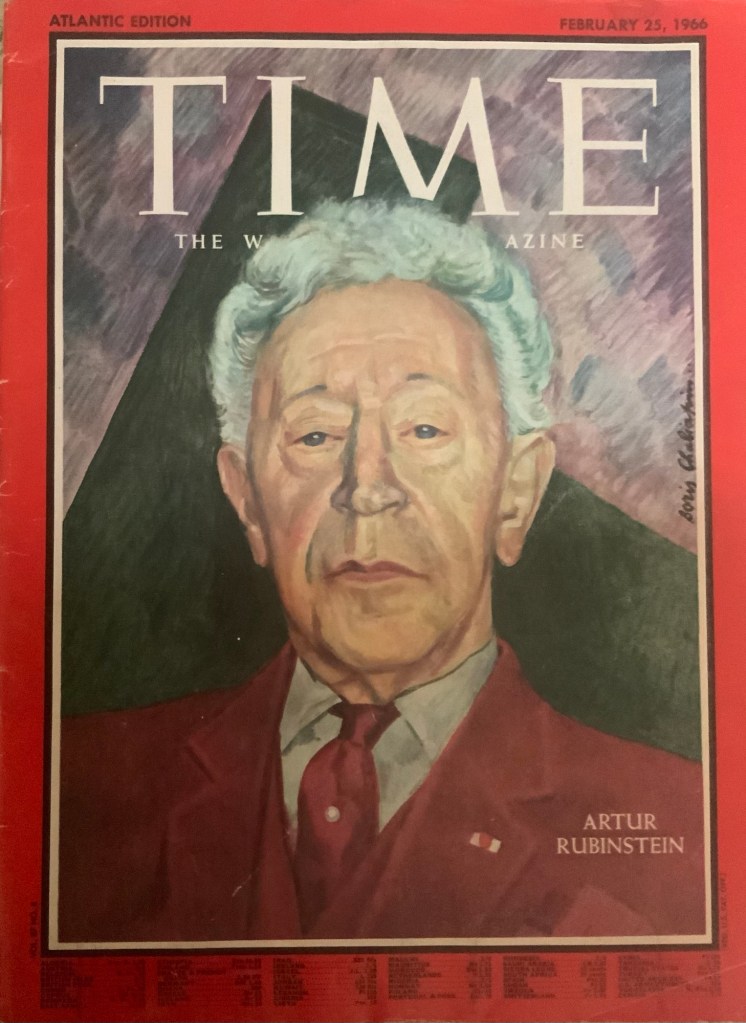

The menacing opening of the development in the bass was answered by the radiance and beseeching beauty of the reply in a question and answer of poignant significance .Leading to the mighty climax where the genial invention of Chopin turns the formal sonata form into a throbbing intensity where form and soul are united in a passionate outpouring finding an outlet only with the gloriously triumphant return of the second subject.A masterly control of balance allowed us to see so clearly a masterpiece opening up before our eyes as rarely before.A coda that was of a nobility and controlled passion that I have only ever witnessed from Rubinstein.

The Scherzo immediately entered with a dynamic rhythmic drive that was never hard or allowed to turn into a vulgar dance .There was a forward movement that was only to be relieved by a Trio of ravishing beauty of chameleonic colours and subtle rubato.

The funeral march entered with whispered insistence with a ponderous and relentless bass over which the melodic line was at first overheard from afar but gradually ,almost imperceptibly,growing in intensity until exploding into a passionate outpouring of overwhelming significance.

The ravishing beauty of the bel canto Trio I have never heard as today where above all there was an architectural shape and unexpected colours from within.The whispered repeats were of a beauty that was so natural that one almost dared not breathe in such rarified air.The end of the Funeral March too was a mere murmur as we in the public barely recognised a work we have known all our lives such was the act of recreation from a great artist of rare sensibility.The last movement was indeed a real wind that passed over the graves as notes became streams of sounds whispered,wailing and almost without form until a glimmer of light at the end of the tunnel brought us to the final tumultuous chords .A movement of such originality that it is no wonder that Chopin’s contemporaries could not understand the visionary genius of a composer who was condemned to die before his fortieth birthday.Like Schubert ,who died even earlier ,both were much criticised for works lacking in formal construction .Theirs was such a revolutionary new vision that it needed another hundred years to pass before being recognised as works of genius.

After the interval a group of pieces by Rameau that was refreshing for the purity of sound and exhilarating for the transcendental ‘ fingerfertigkeit’ that this young artist demonstrated with such simplicity.We have often marvelled at Sokolov with his trills like taut springs of Swiss clock precision but today there was the same mastery but allied to a sense of colour like a prism shining light on unexpected corners of jewels glowing as they caught the light. Has ‘Les tendres plaintes’ ever sounded as beautiful as today where simplicity and beauty were combined with some remarkable colouring just hinted at in the bass? Dynamic playfulness of ‘Les Cyclopes’ with the left hand murmurings adding a throbbing heartbeat to the quixotic melody.There was elegance and delicacy to the two Menuets with the second played with a charming lilt before the whispered return of the first.A hypnotic rhythmic elan to ‘ Les Sauvages’ with a kaleidoscope of colours, and an infectious good humour to Rameau’s famous impersonations in ‘La Poule’. The Gavotte et 6 doubles is a real masterpiece .A remarkable theme and variations with an opening of disarming simplicity and a gradual increase in intensity as the variations become ever more virtuosistic.These pieces by Rameau as played today showed a technical refinement and controlled brilliance that was every bit as breathtaking as the more obvious Black Key Study that Bruce was to astonish us with as his penultimate encore.

Chopin’s Rondo op 2 was the work that Bruce chose to close his first London recital with since his triumph with this very piece in the Chopin competition in Warsaw.There was beguiling dance,dynamic drive and the breathtaking Bel Canto of a supreme stylist who could play with brilliance and the charm of a jeux perlé of another era – the Golden Age of piano playing of the likes of Lhevine,Hoffman or Godowsky. Notes that in this young magicians hands could make the music speak with extraordinary simplicity and subtle beauty.

Even the first encore of the Allemande from Bach’s Fifth French suite was played with refreshing originality with some subtle pointing of the bass and the colours of a pianist who like Van Cliburn said he would never play faster than he could sing. Chopin’s ‘Black Key’ study op.10 n.5 was breathtaking for it’s subtle colouring and astonishing technical brilliance.The last encore Chopin’s Nocturne op. posth in C sharp minor was played with a ravishing sense of balance and the disarming simplicity of this ‘new’ Golden Age .The path that this remarkable young artist is fast showing a world where music is allowed to speak with a voice of such stylish mastery and humanity.

Bruce Liu’s triumphant debut at the Edinburgh Festival

Bruce Liu takes London by storm

Bruce Xiaoyu Liu showing the way to Eutopia for Chopin’s 212th birthday

Stars shine brightly in Warsaw with Dang Thai Son,Bruce Liu and Lukas Geniusas

Franz Joseph Haydn 31 March 1732 – 31 May 1809 Born in Rohrau,Austria .

On 26 May Haydn played his “Emperor’s Hymn” with unusual gusto three times; the same evening he collapsed and was taken to what proved to be to his deathbed.He died peacefully in his own home at 12:40 a.m. on 31 May 1809, aged 77.On 15 June, a memorial service was held in the Schottenkirche at which Mozart’s Requiem was performed. Haydn’s remains were interred in the local Hundsturm cemetery until 1820, when they were moved to Eisenstadt by Prince Nikolaus. His head took a different journey; it was stolen by phrenologists shortly after burial, and the skull was reunited with the other remains only in 1954, now interred in a tomb in the north tower of the Bergkirche!

The 55 Haydn Sonatas are perhaps the least-known treasures of the piano repertoire. In them one can hear Haydn virtually inventing the classical style, from the early, somewhat tentative beginnings, through the bold experiments of the 1770s, to the adventurous late works. As with Beethoven (Haydn’s somewhat recalcitrant student) each sonata is a new exploration, and the element of surprise is ever present. Haydn delights in abrupt transitions, twists and turns, sudden pauses, and apparent non sequiturs; listening to him demands a constant alertness.

Many of Haydn’s string quartets bear curious nicknames (“The Lark,” “The Razor,” “The Frog,” etc.). I am tempted to call the very serious B-minor Sonata “The Bear”; the lumbering bass figure at the beginning, the repeated chorded growls in the bass, and a general air of surly brusqueness give it unusual power. In exquisite contrast, the central Minuet is one of the most delicate and graceful pieces Haydn ever wrote – an unusually Mozartean moment. The bear returns in the minor-key trio, accompanied later on by some angry bees buzzing in the right hand. The Presto hammers away in repeated notes, at the first movement’s opening third, and the bees also return with a vengeance. The end is stark and uncompromising. The b-minor Sonata is part of a group of six piano sonatas which, according to Haydn’s own handwritten catalogue of works, was composed in 1776. The autograph has not survived, and the first edition of 1778 was not authorised. However, numerous copyist’s manuscripts have survived in which Haydn had his six sonatas disseminated.

Franz Joseph Haydn

Sonata in B minor Hob. XVI:32

The jovial, witty and ever-cheerful ‘Papa’ Haydn writing in a minor key? What brought that on?

The 1770s, when Haydn’s Sonata in B minor was composed, was the age of Sturm und Drang (storm and stress) in German culture, an age when aberrant emotions were all the rage in music; and what better tonal avouring than the minor mode to convey these emotions? Composers such as C. P. E. Bach rode this cultural wave with enthusiasm, writing works that elicited powerful, sometimes worrisome, emotions by means of syncopated rhythms, dramatic pauses, wide melodic leaps and poignant harmonies of the type that minor keys were especially adept at providing.It is also important to note that the 1770s was the period in which the harpsichord was gradually giving way to the new fortepiano, precursor of the modern grand, and there is much in this sonata to suggest that it still lingered eagerly on the harpsichord side of things, at least texturally. The kind of writing you find in the first movement, especially, is the sort that speaks well on the harpsichord. Moreover, there are no dynamic markings in the score, as you would expect in a piece that aimed to take advantage of the new instrument’s chief virtue: playing piano e forte.This cross-over period between harpsichord and fortepiano plays out in the nature of the first movement’s two contrasting themes. The first is austere and slightly mysterious, amply encrusted with crisp, Baroque-style mordents on its opening melody notes. The second churns away in constant 16th-note motion – the very thing the harpsichord is good at. And while this second theme is set in the relative major, its subsequent appearance in the recapitulation is re-set in the minor mode, yet a further sign of the serious Sturm und Drang tone that pervades this movement.In place of a lyrical slow movement, Haydn offers us a minuet and trio – but where is the emotional drama in that? Haydn has a plan. His minuet and trio feature thematic material as dramatically contrasting as the first and second themes of the first movement. The minuet is in the major mode, set high in the register, sparkling with trills and astonishing us with melodic leaps everywhere, one as large as a 14th. The trio, normally con gured as sugary relief from the sti formality of courtly dance ritual, is daringly in the minor mode, set low, and grinds grimly away in constant 16th-note motion.

Haydn wouldn’t be Haydn if he didn’t send you away with a toe-tapping finale and such a movement ends this sonata. To that end, Haydn’s go-to rhythmic device is repeated notes, and this nale chatters on constantly at an 8th-note patter, interrupted at random, it would seem, by surprising silences and dramatic pauses – as if to allow the performer to turn sideways and wink at his audience.

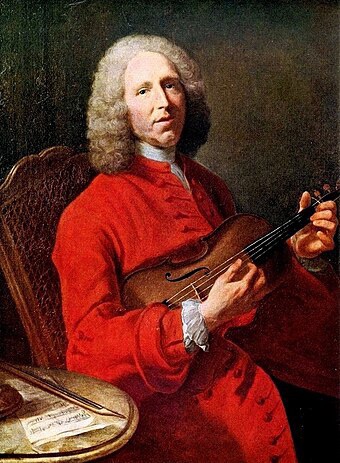

Jean-Philippe Rameau, by Joseph Aved, 1728

Jean-Philippe Rameau, who

was not only a superb organist and composer but also,

in his day, a noted music theorist. The selections in

tonight’s concert are drawn from the suites that make

up his Pièces de clavecin, published in three volumes

over a period of twenty years (1706-26/7). In addition to

dance movements such as the Menuets or the Gavotte,

the suites contain a number of character pieces, with

titles such as Les tendres plaintes (‘The tender

complaints’) and Les cyclopes (both found in the Suite

in D minor). Les sauvages, from the Suite in in G minor,

was inspired by a performance Rameau attended in

1725 of a dance by Indigenous Americans brought to

Paris, and became so popular that he reworked it for

inclusion in his opera Les indes galantes. La poule,

meanwhile, is full of dramatic contrasts and features a

theme made up of repeated notes that musically

represents the clucking of the hen.

The French Baroque composer Jean – Philippe Rameau wrote three books of Pièces de clavecin for the harpsichord .The first, Premier Livre de Pièces de Clavecin, was published in 1706 ; the second, Pièces de Clavessin, in 1724; and the third, Nouvelles Suites de Pièces de Clavecin, in 1726 or 1727. They were followed in 1741 by Pièces de clave in En concerts, in which the harpsichord can either be accompanied by violin (or flute) and viola da gamba or played alone. An isolated piece, “La Dauphine“, survives from 1747.

Pièces de Clavessin (1724)

Two played tonight are from 1724 and are the first and eighth from his Suite in D : Les Tendres Plaintes – Les Cyclopes

- Les Tendres Plaintes. Rondeau .An almost tongue-in-cheek character piece, with a title so hackneyed that Rameau was surely poking a bit of fun: Les tendres plaintes (‘The tender sighs ‘) It is nevertheless a ravishing pearl piece , and Rameau clearly thought enough of it to rework it as a ballet movement in Zoroastre (1749).

- Les Niais de Sologne – Premier Double des Niais – Deuxième Double des Niais

- Les Soupirs. Tendrement

- La Joyeuse. Rondeau

- La Follette. Rondeau

- L’Entretien des Muses

- Les Tourbillons. Rondeau

- Les Cyclopes. Rondeau. Is the jewel of the set with a musical description of the mythological smithies who forged Jupiter’s thunderbolts in the deep recesses of the Earth. Here Rameau uses his special technique of ‘batteries’ which he claimed to have invented. As he explains in the preface to the 1724 collection: ‘In one of the batteries the hands make between them the consecutive movement of two drumsticks; and in the other, the left hand passes over the right to play alternately the bass and treble.’ Incidentally, Les cyclopes is believed to be one of the pieces played by the Jesuit Amiot before the Chinese Emperor; sadly, it seems to have not made much of an impression.

- Le Lardon. Menuet

- La Boiteuse

Nouvelles Suites de Pièces de Clavecin (1726–1727)

Suite in G major/G minor, RCT 6

- Les Tricotets. Rondeau

- L’indifférente

- Menuet 1- Menuet 11

- La Poule Among Rameau’s harpsichord pieces, La Poule is certainly one of the most famous. It is a perfect illustration of the French harpsichord style of the 17th and 18th centuries, characterized by the use of numerous ornaments, the concern for the picturesque and descriptive intentions, and the supreme elegance and refinement of the melody.

- Les Triolets

- Les Sauvages …Best and most celebrated pieces, Les Sauvages, later used in his opéra ballet Les Indes galantes (first performed 1735). The following year, at the age of 42, he married a 19-year-old singer, who was to appear in several of his operas and who was to bear him four children.

- L’Enharmonique. Gracieusement.

- L’Égyptienne

Suite in A minor, RCT 5

- Allemande

- Courante

- Sarabande

- Les Trois Mains

- Fanfarinette

- La Triomphante

- Gavotte et six doubles This is a theme and six variations (termed doubles) for harpsichord. The theme is titled Gavotte. The work is in A minor and has little harmonic interest and a simple melody

Fryderyk Franciszek Chopin 1 March 1810 – 17 October 1849

Chopin at 25, by his fiancée Maria Wodzinska, 1835

The Piano Sonata No. 2 in B flat minor , op .35 was completed by Chopin while living in Georges Sand’s manor in Nohant some 250 km (160 mi) south of Paris ,a year before it was published in 1840.

Some time after writing the Marche funèbre, Chopin composed the other movements, completing the entire sonata by 1839. In a letter on 8 August 1839, addressed to Fontana, Chopin wrote:

‘I am writing here a Sonata in B flat minor which will contain my March which you already know. There is an Allegro, then a Scherzo in E flat minor, the March and a short Finale about three pages of my manuscript-paper. The left hand and the right hand gossip in unison after the March. … My father has written to say that my old sonata [in C minor, Op. 4] has been published by [Haslinger] and that the German critics praise it. Including the ones in your hands I now have six manuscripts. I’ll see the publishers damned before they get them for nothing.’

When the sonata was published in 1840 in the usual three cities of Paris,Leipzig and London the London and Paris editions indicated the repeat of the exposition as starting at the very beginning of the movement (at the Grave section). However, the Leipzig edition designed the repeat as beginning at the Doppio movimentosection. Although the critical edition published by Breitkopf & Hartel (that was edited, among others, by Franz Liszt, Carl Reinecke and Johannes Brahms ) indicate the repeat similarly to the London and Paris first editions, almost all 20th-century editions are similar to the Leipzig edition in this regard. Charles Rosen argues that the repeat of the exposition in the manner perpetrated by the Leipzig edition is a serious error, saying it is “musically impossible” as it interrupts the D♭major cadence (which ends the exposition) with the B♭ minor accompanimental figure.Others agree, calling the repeat to the Doppio movimento“nonsense”. However some others advocates for excluding the Grave from the repeat of the exposition, citing in part that Karol Mikuli’s 1880 complete edition of Chopin contained a repeat sign after the Grave in the first movement of the Piano Sonata No. 2. Mikuli was a student of Chopin from 1844 to 1848 and also observed lessons Chopin gave to other students – including those where this sonata was taught – and took extensive notes.

Although the third movement was originally published as Marche funèbre, Chopin changed its title to simply Marche in his corrections of the first Paris edition.In addition, whenever Chopin wrote about this movement in his letters, he referred to it as a “march” instead of a “funeral march”.Kallberg believes Chopin’s removal of the adjective funèbre was possibly motivated by his contempt for descriptive labels of his music.After his London publisher Wessel & Stapleton added unauthorised titles to Chopin’s works, including The Infernal Banquet to his first scherzo in B minor Op. 20, the composer, in a letter to Fontana, wrote:

‘Now concerning [Christian Rudolf Wessel], he is an ass and a cheater … if he has lost on my compositions, it is doubtless due to the stupid titles he has given them in spite of my repeated railings to [Frederic Stapleton]; that if I listened to the voice of my soul, I would have never sent him anything more after those titles.’

In 1826, a decade before he wrote this movement, Chopin had composed another Marche funèbre in C minor, which was published posthumously as Op. 72 No. 2.Chopin, who wrote pedal indications very frequently, did not write any in the Finale except for the very last bar. Although Moritz Rosenthal (a pupil of Liszt and Mikuli) claimed that the movement should not be played with any pedal except where indicated in the last measure, Rosen believed that the “effect of wind over the graves”, as Anton Rubinstein described this movement, “is generally achieved with a heavy wash of pedal”.The first major criticism, by Schumann , appeared in 1841 and was critical of the work. He described the sonata as “four of [his] maddest children under the same roof” and found the title “Sonata” capricious and slightly presumptuous.He also remarked that the Marche funèbre “has something repulsive” about it, and that “an adagio in its place, perhaps in D-flat, would have had a far more beautiful effect”.In addition, the finale caused a stir among Schumann and other musicians. Schumann said that the movement “seems more like a mockery than any [sort of] music”,and when Felix Mendelssohn was asked for an opinion of it, he commented, “Oh, I abhor it”. Franz Liszt, a friend of Chopin’s, remarked that the Marche funèbre is “of such penetrating sweetness that we can scarcely deem it of this earth”

Chopin heard Nicola Paganini play the violin in 1829 and composed a set of variations, Souvenir de Paganini. It may have been this experience that encouraged him to commence writing his first Etudes (1829–1832), exploring the capacities of his own instrument.After completing his studies at the Warsaw Conservatory, he made his debut in ViennaHe gave two piano concerts and received many favourable reviews – in addition to some commenting (in Chopin’s own words) that he was “too delicate for those accustomed to the piano-bashing of local artists”. In the first of these concerts, he premiered his Variations on ‘La ci darem la mano ‘op 2 variations on a duet from Mozart’s opera Don Giovanni ) for piano and orchestra.He returned to Warsaw in September 1829,where he premiered his Piano Concerto n.2 Op. 21 on 17 March 1830.

The final piece in tonight’s programme formed the

centrepiece of the teenage Chopin’s debut concert in

Vienna, at the Kärntertortheater (which housed the

première of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony) in August 1829.This work, his Op. 2 Variations on ‘Là ci darem la

mano’ from Mozart’s Don Giovanni, has come down to

us in two versions, one for piano and orchestra and one

for solo piano. In the original opera, the duet is heard

during the first act, where Don Giovanni tries to seduce

Zerlina into coming to his castle, and sings to her,

‘There we will give each other our hands, there you will

say “yes” to me. See, it’s not far; let’s go, my dear, from

here’. Mozart’s charming melody was very popular in

the early 19th Century and formed the basis of

numerous other pieces, including a set of variations for

cello and piano by Beethoven (WoO. 28). It is therefore

hardly surprising that the 19-year-old Chopin chose his

own Variations on this theme to introduce himself to

the Viennese public.

The work opens with a slow, improvisatory

introduction, imbued with a sense of expectation.

When the theme does appear, it is presented cheerfully

and simply; however, Chopin soon launches into his

first variation, a virtuosic miniature in the so-called

‘brilliant style’, which then rapidly gives way to an even

faster variation, where the theme is presented in demi-

semiquaver motion in the right hand. In the more lyrical

third variation, it is the left hand’s turn at delicate

figuration, against the melody in the right hand. The

fourth variation, marked ‘con bravura’, is full of

treacherous leaps, just as exciting to watch as to listen

to, whilst the fifth takes a dramatic and deeply

expressive turn into B flat minor. Chopin saves his best

until last, however, with a spectacular finale in which

Mozart’s theme is cast as a brilliant polonaise. With

these Variations, dedicated to his school friend Tytus

Woyciechowski, the young virtuoso was propelled to

stardom. As Chopin wrote to his parents after the

Vienna concert, ‘at the end, there was so much

clapping that I had to come out and bow again’; the

work’s publication the following year, meanwhile,

inspired Robert Schumann to famously remark: ‘Hats

off, gentlemen – a genius!’.

On 7 December 1831, Chopin received the first major endorsement from an outstanding contemporary when Schumann reviewing the Op. 2 Variations in the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung (his first published article on music), declared: “Hats off, gentlemen! A genius.”On 25 February 1832 Chopin gave a debut Paris concert in the “salons de MM Pleyel” at 9 rue Cadet, which drew universal admiration. The critic Francois- Joseph Fetis wrote in the Revue et gazette musicale : “Here is a young man who … taking no model, has found, if not a complete renewal of piano music, … an abundance of original ideas of a kind to be found nowhere else …”After this concert, Chopin realised that his essentially intimate keyboard technique was not optimal for large concert spaces. Later that year he was introduced to the wealthy Rothschild banking family, whose Patronage also opened doors for him to other private salons of social gatherings of the aristocracy and artistic and literary elite. By the end of 1832 Chopin had established himself among the Parisian musical elite and had earned the respect of his peers such as Hiller, Liszt, and Berlioz. He no longer depended financially upon his father, and in the winter of 1832, he began earning a handsome income from publishing his works and teaching piano to affluent students from all over Europe.This freed him from the strains of public concert-giving, which he disliked.

Chopin seldom performed publicly in Paris. In later years he generally gave a single annual concert at the Salle Pleyel, a venue that seated three hundred. He played more frequently at salons but preferred playing at his own Paris apartment for small groups of friends. The musicologist Arthur Hedley has observed that “As a pianist Chopin was unique in acquiring a reputation of the highest order on the basis of a minimum of public appearances – few more than thirty in the course of his lifetime.”

First prize winner of the 18th Chopin Piano Competition 2021 in Warsaw, Bruce Liu’s “playing ofbreathtaking beauty” (BBC Music Magazine) has secured his reputation as one of the most excitingtalents of his generation and contributed to a “rock-star status in the classical music world” (TheGlobe and Mail).

Highlights of Bruce Liu’s 2023/24 season include international tours with the Tonhalle-OrchesterZürich and Paavo Järvi, the Philharmonia Orchestra and Santtu-Matias Rouvali, and the WarsawPhilharmonic and Andrey Boreyko, as well as the Münchener Kammerorchester in a play-directprogramme. Furthermore, he makes anticipated debuts with the New York Philharmonic, FinnishRadio Symphony, Danish National Symphony, Gothenburg Symphony and Singapore SymphonyOrchestras. He works regularly with many of today’s most distinguished conductors such as GustavoGimeno, Yannick Nézet-Séguin, Gianandrea Noseda, Rafael Payare, Vasily Petrenko, Jukka-PekkaSaraste, Lahav Shani and Dalia Stasevska.

Bruce Liu has performed globally with major orchestras including the Wiener Symphoniker,Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, Rotterdam Philharmonic, Orchestre Philharmonique duLuxembourg, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Los Angeles Philharmonic, San Francisco Symphony,The Philadelphia Orchestra, Orchestre symphonique de Montréal and NHK Symphony Orchestra.

As an active recitalist, he appears at major concert halls such as the Carnegie Hall, WienerKonzerthaus, BOZAR Brussels and Tokyo Opera City, and makes his solo recital debuts in the2023/24 season at the Concertgebouw Amsterdam, Philharmonie de Paris, Wigmore Hall London,Alte Oper Frankfurt, Kölner Philharmonie and Chicago Symphony Center.

Having been a regular guest at the Rheingau Musik Festival since 2022, Liu will return in summer2024 to feature in a series of wide-ranging events. In recent years, he has appeared at LaRoque-d’Anthéron, Verbier, KlavierFestival Ruhr, Edinburgh International, Gstaad Menuhin andTanglewood Music Festivals.

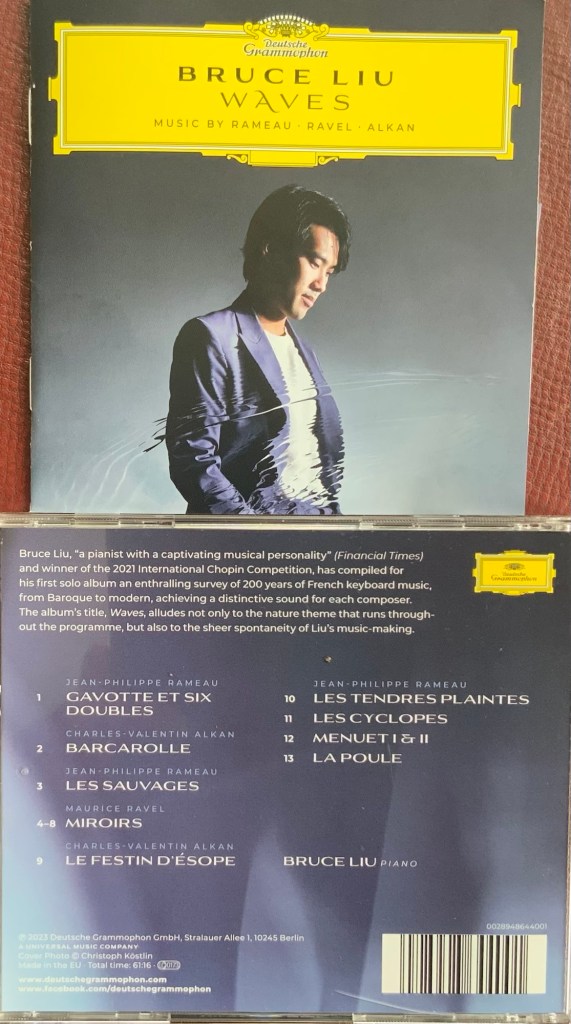

An exclusive recording artist with Deutsche Grammophon, Liu’s highly anticipated debut studioalbum “Waves” spanning two centuries of French keyboard music (Rameau, Ravel, Alkan) is beingreleased in November 2023. His first album featuring the winning performances from the ChopinInternational Piano Competition received international acclaim including the Critics’ choice, Editor’schoice, and “Best Classical Albums of 2021” from the Gramophone Magazine.

Bruce Liu studied with Richard Raymond and Dang Thai Son. Born in Paris to Chinese parents andbrought up in Montréal, Liu’s phenomenal artistry has been shaped by his multi-cultural heritage:European refinement, North American dynamism and the long tradition of Chinese culture.

Christopher Axworthy Dip.RAM ,ARAM

‘The Willie Wonka of the Piano’ Jed Distler