Another extraordinary recital by Patrick Hemmerlé who seems to digest the piano repertoire,conventional and unconventional, with a voracious appetite that is quite astonishing.

Intelligence,curiosity,mastery and simplicity. A sense of communication and effortless beauty that brings us scores of notorious difficulty time after time.Today was even more astonishing as he played one of the most difficult pieces in the piano repertoire with a smile on his face as he lived Mozart’s drama describing each character with the same effect that we would have experienced in the theatre.

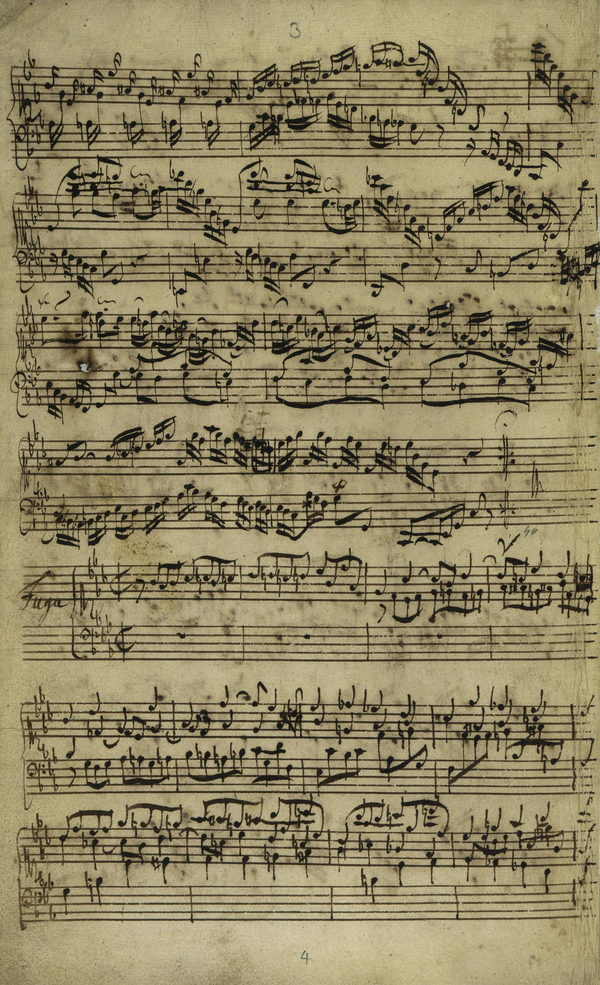

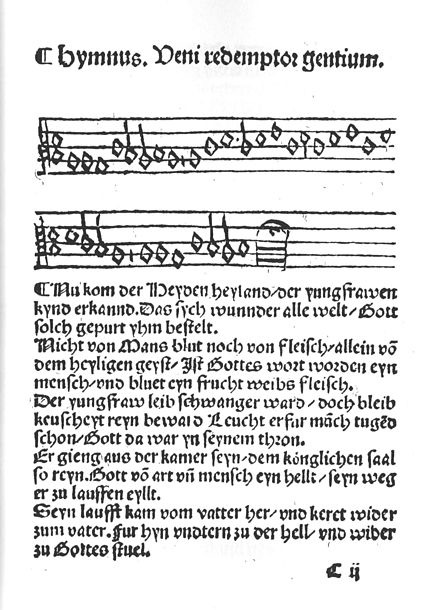

Bach that just spun from his fingers with the crystalline clarity of the Fantasia in C minor or the searing intensity of ‘Nun Komm…….’ in Busoni’s transcription.Patrick,an ever more Busonian character himself , had even made his own transcription of the elaborate weaving of Bach’s ‘Ich habe Genug’ that he found time to write whiling away the boredom of being far from a piano with Covid!

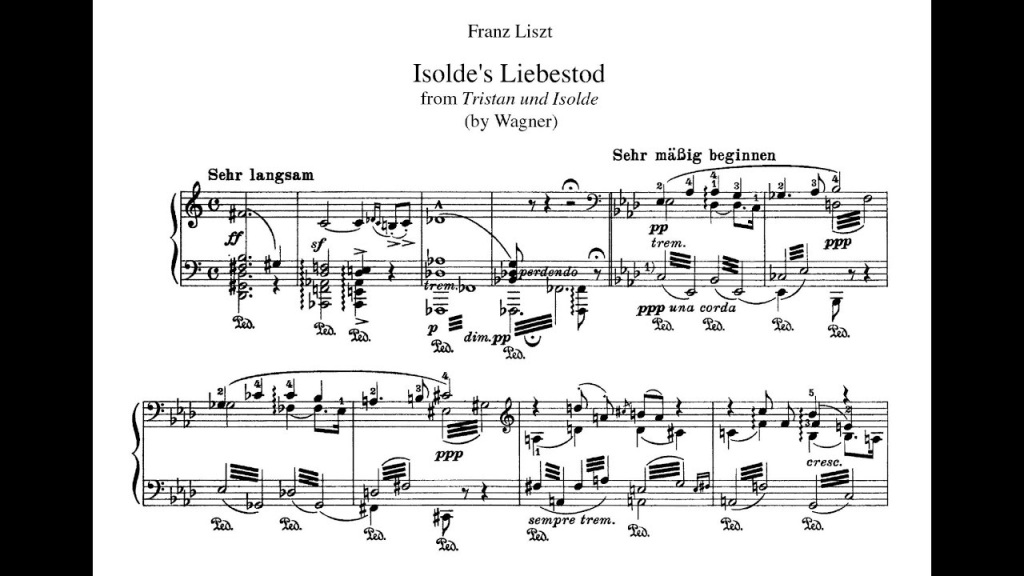

Wagner’s heart rending passionate outpouring so lusciously described in his father in law’s genial hands was mirrored by the sparse but poignant transcription,or more pointedly a ramble by that illusive figure Percy Grainger.

Der Rosenkavalier where with just the unmistakeable stroke of chiming chords he could create the same atmosphere of Strauss’s sumptuous score .It reminded me very much of another Busonian figure : Ronald Stevenson whose Grimes Fantasy was similarly poignant with Britten’s unmistakable chord progressions creating the same desolate atmosphere as the crowds swaying on stage.

It needs just one saliant detail to describe so grafically an entire opera.

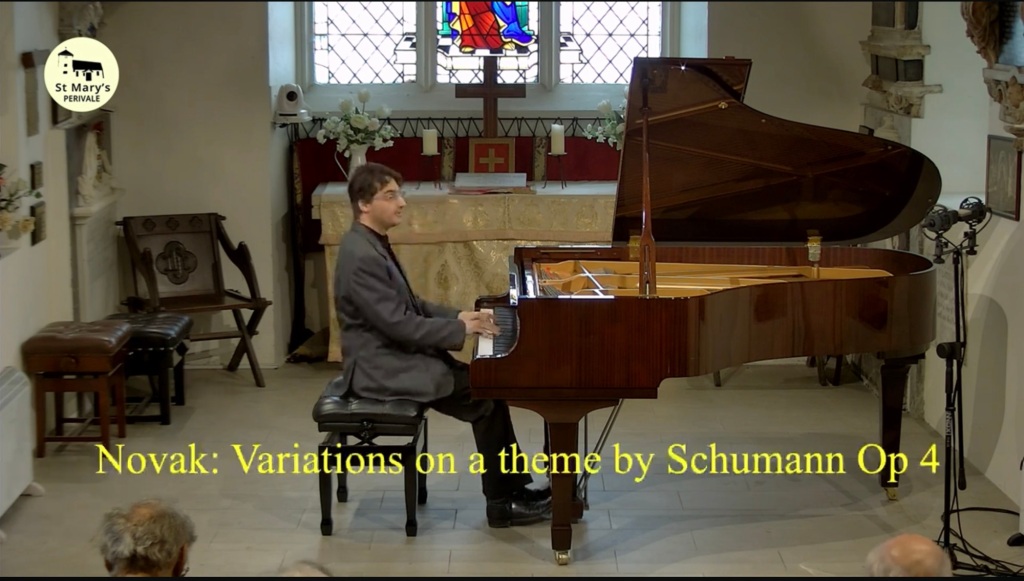

The variations by Novak ,that the composer himself had not thought worthy of his later compositions, in Patrick’s hands revealed a set of variations that were so much more interesting and varied than the rather repetitive monocoloured theme from Schumann’s usually richly ‘coloured leaves’ op. 99.

If the Don Juan Fantasy was astonishing for it’s fearless virtuosity and breathtaking vision it was the little waltz by Schubert played as an encore that truly stole our hearts.Beauty,simplicity and a ravishing sense of balance combined to calm the red hot cauldron with which Liszt had described Mozart’s great operatic masterpiece.

It also was of great interest as Schubert gave it to his friend Kupelwieser as a wedding present in 1826 and it was never written down.A family descendent played it to Strauss in 1943 who did write it down and it was eventually published in 1970.

Yet another sting in the tail for this remarkable young artist who never fails to astonish,inform or seduce.

Patrick Hemmerlé is one of Europe’s foremost and most enigmatic pianists. Refusing to follow musical traditional conventions, he has forged a unique path in the musical world which leaves him free to immerse himself with singular dedication into the repertoire and musical expression resonating with the profoundest convictions. The results are interpretations of startling insight and originality. By dauntlessly performing all 24 Chopin Etudes or 24 of Bach’s Preludes and Fugues in a single concert, as well as championing lesser-known composers he feels a deep affinity for, he has developed a reputation as an original with something out of the ordinary to say,

French born and trained at the Conservatoire de Paris under Billy Edie, and laureate of many international piano competitions, he now lives in Cambridge, England, where he has built up a staunchly loyal following. He also performs all over the world and recent engagements have taken him to New York, Berlin, Paris, Vienna and Prague and China. He has published 5 CDs, and his latest recording project to be issued shortly, is a pairing of Bach’s Well Tempered Clavier and Fischer’s Ariadne Musica. Patrick is a member of Clare Hall, where he is in charge of the concert programme.

Patrick Hemmerlé at St Mary’s The Mastery and Mistery of a fervent believer

Réminiscences de Don Juan (S. 418) on themes from mozart’s Mozart’s 1787 opera Don Giovanni

As Busoni says in the preface to his 1918 edition of the work, the Réminiscences carries “an almost symbolic significance as the highest point of pianism.” Liszt wrote the work in 1841 and published a two-piano version (S. 656) in 1877. It is extremely technically demanding and considered to be among the most taxing of Liszt’s works and in the entire repertoire . Neuhaus simply stated that with the exception of Ginzburg probably nobody but the pianola played without smudges.” https://youtube.com/watch?v=5VU7NsF5E1E&feature=shared

It was the final piece for Horowitz’s graduation concert at the Kiev’s conservatory; at the end all the professors stood up to express their approval. Horowitz, after claiming to Backhaus that the most difficult piano piece he ever played was Liszt’s Feux-follets without hesitation, he added that Réminiscences de Don Juan is not an easy piece either. Horowitz had it in his concert programmes, as well as the Liszt Sonata, which was not often played at the time, in his early years in Europe

Scriabin injured his right hand overpracticing this piece and Balakirev’s Islamey , and wrote the funeral march of his First Piano Sonata in memory of his damaged hand.

Tristan and Isolde is a musical drama in three acts written by Richard Wagner between 1857 and 1859, and premiered in 1865. Two years after the debut of the work at the National Theater of Munich, Franz Liszt (who was Wagner’s father in law) made a piano transcription of Isolde’s final aria. The piece, called “Mild und leise”, was referred to as “Verklärung” (Transfiguration) by Wagner. Liszt prefaced his transcription with a four bar excerpt from the Love Duet from Act II, which in the opera is sung to the words “sehnend verlangter Liebestod”. Accordingly, he referred to his transcription as ‘Liebestod’. Later it was designated with the catalogue number S. 447. Liszt’s transcription (which underwent a revision in 1875) became famous in Europe well before Wagner’s opera reached most places.

Vitězslav NOVÁK (1870-1949)

Variations on a theme by Schumann, Op.4 (1893)

Viktor Novák

5 December 1870 Bohemia 18 July 1949 Czechoslovakia

He was a Czech composer and academic teacher at the Prague Conservatory Stylistically, he was part of the neo- romantic tradition, and his music is considered an important example of Czech modernism He worked towards a strong Czech identity in culture after the country became independent in 1918. Born Viktor

he changed his name to Vítězslav to identify more closely with his Czech identity, as many of those of his generation had already done. At the conservatory, he studied piano and attended Dvorak’s masterclasses in composition

His chamber music includes some fine piano music such as the variations on a theme of Schumann of 1893, the Sonata Eroica of 1900, Exotion of 1911, the six sonatinas of 1919–1920 and Pan, op 43 an important work left out of Michaels Kennedy’s inadequate Oxford Concise Dictionary of Music. There are the Reminiscences Op 6 of 1884 and Songs of a Winter Night Op 30, the final burleske of which is a foot-tappper, and, in 1920, Novák put together twenty-one short piano pieces which he entitled Mladi (Youth) with the Opus number 55.

Most of his chamber music are early works and include two piano trios in G minor of 1892 and D minor of 1902, a Piano Quartet revised in 1899, a Piano Quintet revised in 1897, three string quartets (1899, 1905 and 1930), and a Cello Sonata of 1941.His Piano Concerto in E minor of 1895 apparently not performed until about 20 years later and which Novák referred to as a monster.Dvorak helped Novák considerably and encouraged him to study philosophy as well. But, by the mid 1890s, Novák was in crisis. He could not find an original voice for his music and despaired sinking into depression. He travelled to a remote region on the borders of Bohemia and Moravia and fell in love with Slovak folk songs which lifted his spirits. He collected many of these songs and seem to fuse them within his own work. It was this contact with nature that inspired him and he felt freed from traditional forms as in the work of the great masters and his mature music probably owes most to Richard Strauss than Brahms

His early works shows a debt to Brahms with his Serenade in F for orchestra of 1894 and the Orchestral Bohemian dances of 1897. He revised the serenade in the last year of his life.But, by far, the most impressive symphonic poem is De Profundis Op 67 of 1941 written during the Nazi occupation. Novák made it clear that he hated the Nazis and could have been arrested for his outspoken views. The title comes from Psalm 130, “Out of the depths have I cried unto Thee, O Lord.” and the score is headed up, “consecrated to the suffering of the Czech people during the German reign of terror 1939–1945.” The large orchestra includes a part for organ played by Jiři Reinberger at the premiere in Brno on 20 November 1941 with the Czech Radio Symphony Orchestra under Bretislav Bakala. In Brno, Czech people were still being shot and hung simply for the amusement of the German people.He had composed another large scale symphony between 1931–1934 called the Autumn Symphony which is a choral symphony. But his finest choral piece is generally agreed to be The Spectre’s Bride of 1912–1913.

Percy Aldridge Grainger (born George Percy Grainger; 8 July 1882 – 20 February 1961) was an Australian-born composer, arranger and pianist who moved to the United States in 1914 and became an American citizen in 1918. In the course of a long and innovative career he played a prominent role in the revival of interest in British folk music in the early years of the 20th century. Although much of his work was experimental and unusual, the piece with which he is most generally associated is his piano arrangement of “Country Gardens”.

Grainger was a great admirer of the music of Richard Strauss, considering him to be a genius and ‘a humane soul whose music overflowed with the milk of human kindness’. Meetings between the two composers took place on various occasions during the early part of the twentieth century, and Strauss was on at least two occasions to conduct Grainger’s music in Germany. Work commenced on the Ramble on Love (‘Ramble on the love-duet in the opera “The Rose-Bearer” [Der Rosenkavalier] FSFM No 4’) before 1920. But it was his mother’s suicide in 1922 that drove Grainger to complete this most elaborate of all his piano paraphrases, with her name obliquely enshrined in the title. It is one of the most meticulously notated piano pieces in the repertoire, with copious use of the sostenuto (middle) pedal where the sumptuous sound world of Strauss is conjured up to dazzling effect in this transcription that marks the full range and summit of Grainger’s pianism.Except for three months’ formal schooling as a 12-year-old, during which he was bullied and ridiculed by his classmates, Percy was educated at home.Rose, an autodidact with a dominating presence, supervised his music and literature studies and engaged other tutors for languages, art and drama.At the age of 10 he began studying piano under Louis Pabst, a German-born graduate of the Moscow Conservatory, Melbourne’s leading piano teacher. Grainger’s first known composition, “A Birthday Gift to Mother”, is dated 1893.Pabst arranged Grainger’s first public concert appearances, at Melbourne’s Masonic Hall in July and September 1894. After Pabst returned to Europe in the autumn of 1894, Grainger’s new piano tutor, Adelaide Burkitt, arranged for his appearances at a series of concerts in October 1894 at Melbourne’s Royal Exhibition Building . The size of this enormous venue horrified the young pianist; nevertheless, his performance delighted the Melbourne critics, who dubbed him “the flaxen-haired phenomenon who plays like a master”.This public acclaim helped Rose to decide that her son should continue his studies in Germany.He left Australia at the age of 13 to attend the Hoch Conservatory in Frankfurt .

Grainger’s biographer, records that during his Frankfurt years, Grainger began to develop sexual appetites that were “distinctly abnormal”; by the age of 16 he had started to experiment in flagellation and other sado-masochistic practices, which he continued to pursue through most of his adult life. Bird surmises that Grainger’s fascination with themes of punishment and pain derived from the harsh discipline to which Rose had subjected him as a child.

Between 1901 and 1914 he was based in London, where he established himself first as a society pianist and later as a concert performer, composer, and collector of original folk melodies. As his reputation grew he met many of the significant figures in European music, forming important friendships with Delius and Grieg . He became a champion of Nordicmusic and culture, his enthusiasm for which he often expressed in private letters, sometimes in crudely racial or anti-Semitic terms.

In 1914, Grainger moved to the United States, where he lived for the rest of his life, though he travelled widely in Europe and Australia.

Bach’s second autograph of the Fantasia and Fugue in C minor, BWV 906: p. 3, showing the end of the Fantasia and the start of the Fugue.

Fantasia and Fugue in C minor, BWV 906, is an unfinished work composed by sometime during Bach’s tenure in Leipzig (1723–1750). The work survives in two autograph scores, one with the fantasia alone, and the other, believed to have been penned around 1738 in which the fugue is incomplete.It is notable for being one of Bach’s latest compositions in the prelude and fugue format.

In 1802 Forkel,the first biographer of Bach described two keyboard fantasies by Bach .He sees the first of these, the Chromatic Fantasia BWV 903 as “unique and unequalled”, and the second, the one in C minor (BWV 906), as a work of different character, “rather the Allegro of a Sonata”. Unaware of the composition’s second autograph, which was only discovered in Dresden in 1876, he thinks that the Fugue is unconnected to the Fantasia and that the end of the Fugue is likely by another composer.

Busoni used the fantasia and his own completion of the fugue in his Fantasia ,Adagio e Fuga BV B37.

“Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland” (original: “Nu kom der Heyden heyland”, English: “Savior of the nations, come“, literally: Now come, Saviour of the heathen) is a Lutheran chorale of 1524 with words written by Martin Luther , based on “Veni redemptor gentilmente ” by Ambrose and a melody, Zahn 1174, based on its plainchant.

The song was the prominent hymn for the first Sunday of Advent for centuries. It was used widely in organ settings by Protestant Baroque composers, most notably J.S. Bach who also composed two church cantatas beginning with the hymn.

Bach arranged the cantata during his career (BWV 699). There have been many variations of Bach’s arrangement. One of the most respected solo instrumental versions is one by Busoni in his Bach- Busoni Editions .

Ich habe genug (original: Ich habe genung, English: “I have enough” or “I am content”), BWV 82,is a cantata by Bach which he composed bass in Leipzig in 1727 for the Feast Mariae Reinigung(Purification of Mary) and first performed it on 2 February 1727. In a version for soprano BWV 82a, possibly first performed in 1731, the part of the obbligato oboe is replaced by a flute . Part of the music appears in the Notebook for Anna Magdalena Bach . The cantata is one of the most recorded and performed of Bach’s sacred cantatas. The opening aria and so-called “slumber aria” are regarded as some of the most inspired creations of Bach.

The gift of a waltz encore

Leopold Kupelwieser (17 October 1796, Markt Piesting – 17 November 1862, Vienna) was an Austrian painter.

He was the son of Johann Baptist Georg Kilian Kupelwieser (1760–1813), co-owner of a factory that produced tableware

Leopold Kupelwieser was an artist, born in 1796, and a friend of Schubert. The artist got married in 1826. To honor them, Schubert composed the couple a little waltz in G flat major. According to lore, the waltz was never written down. It was played and enjoyed by descendants of the couple, generation after generation. Finally, one of these descendants played the waltz for Richard Strauss. This was during World War in 1943. Strauss transcribed the waltz—which was at last published in 1970.

“Very delicate,” says Muti of the Kupelwieser Waltz, and “very nostalgic.” Also expressive of “best wishes for the marriage and for the future of this couple.”

Just before he plays the piece, he says, “It’s quite unknown but very beautiful.”