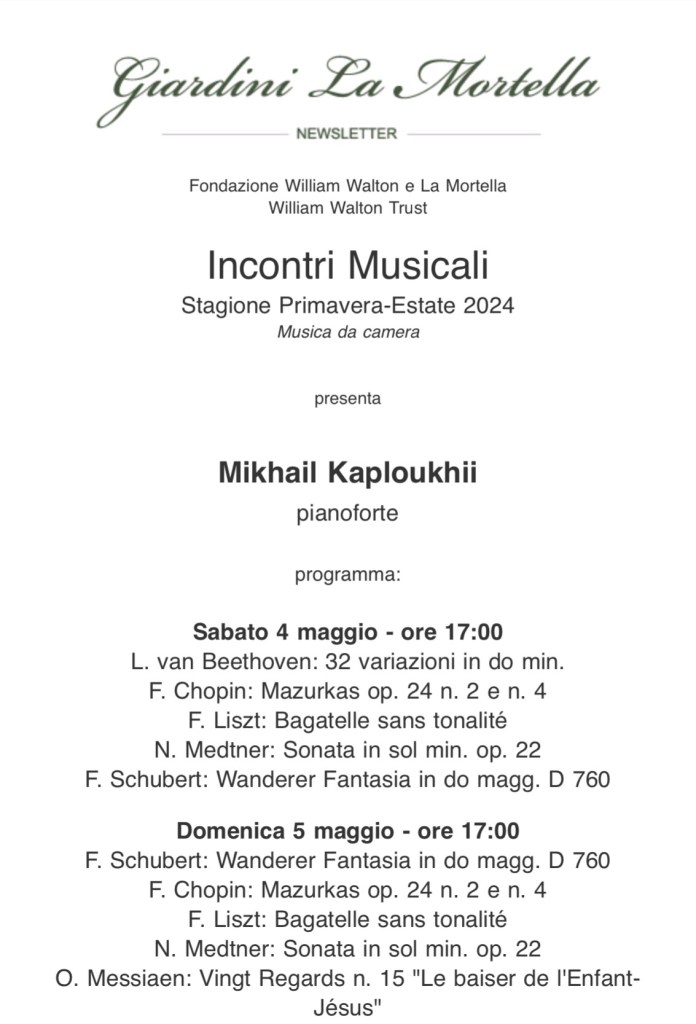

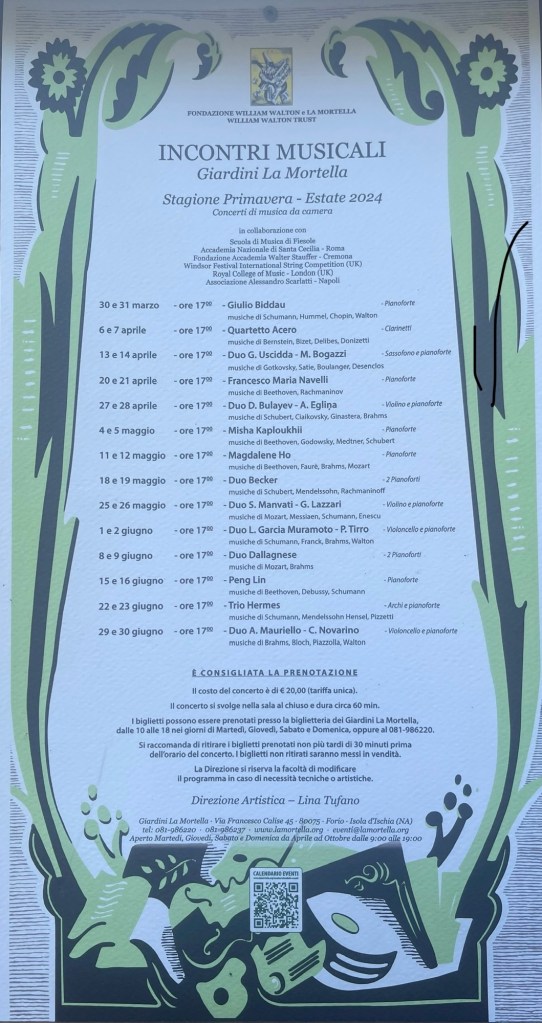

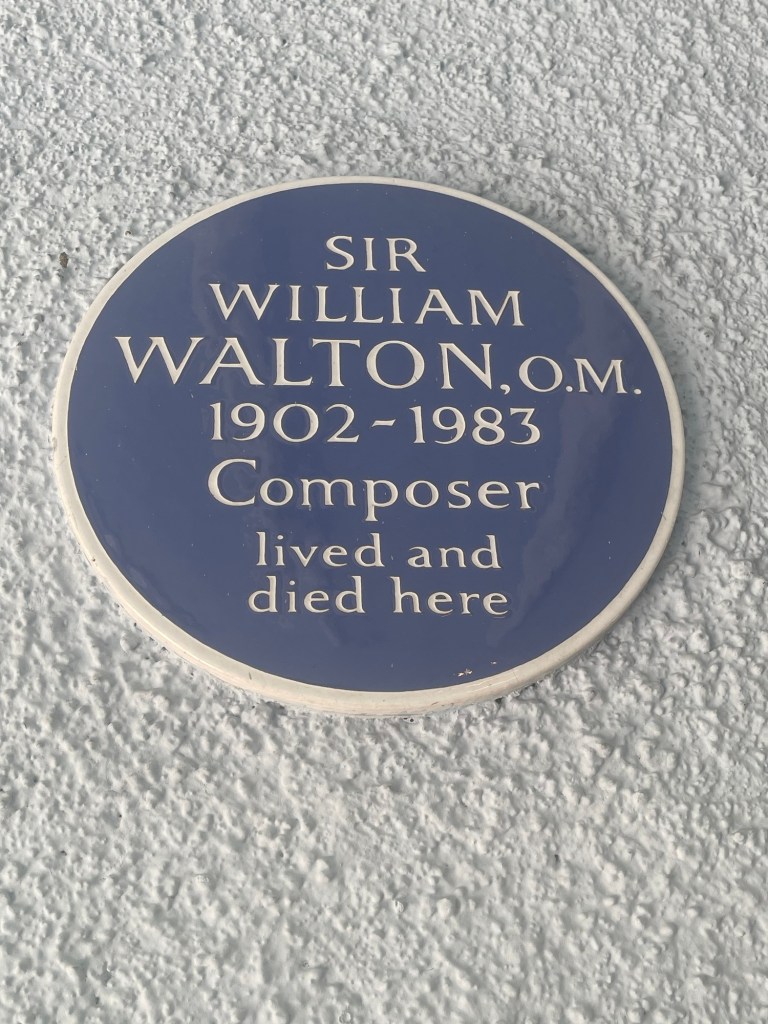

Playing of extraordinary clarity and mastery on Ischia today from Misha Kaploukhii .From Beethoven to Schubert via Chopin,Liszt,Medtner and Brahms .Whatever he played there was a dynamic drive and authority that was quite overwhelming. https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2024/02/17/hats-off-the-chappell-gold-medal-has-uncovered-a-genius/ Having recently won one of the two top prizes at the Royal College of Music in London together with Magdalene Ho , the artistic director of La Mortella ,Lina Tufano immediately invited them both to play in this paradise of music and nature that was an oasis for the Waltons whose express wish was to give a platform to talented young musicians at the start of their careers.

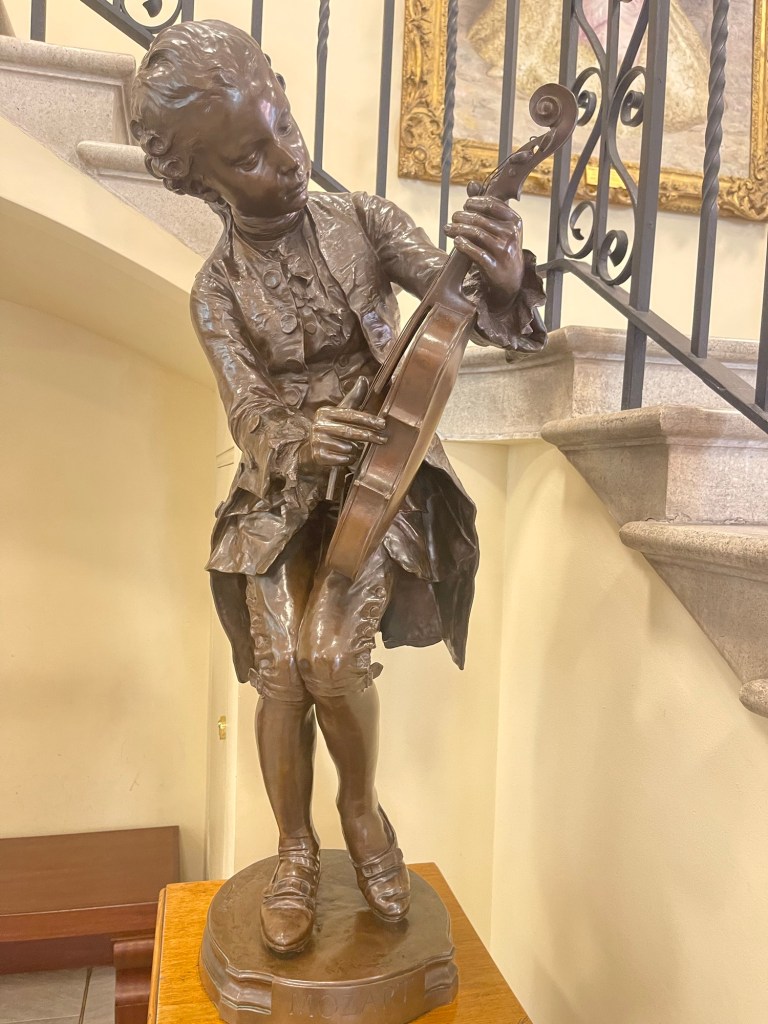

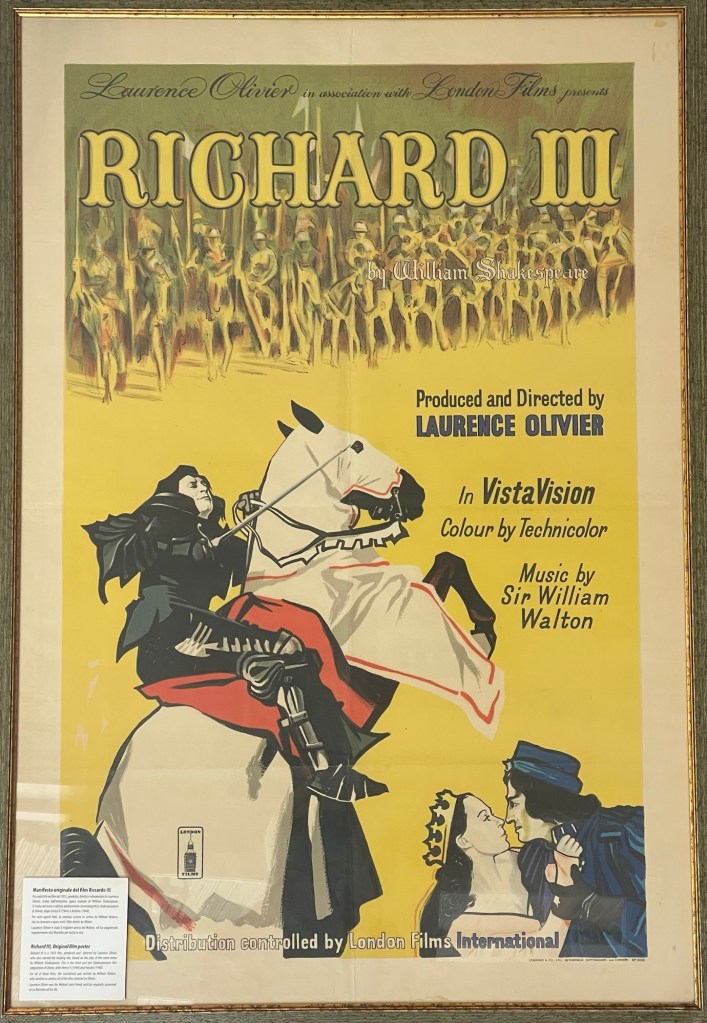

A full house despite a very rough sea to reach this paradise of Ischia that is just off the bay of Naples. And so it was to Beethoven that Misha opened the first of his two afternoon recitals.The 32 Variations in C minor, a key that so often signifies defiance and nobility for Beethoven as it did too for Mozart. It was with a gesture of aristocratic nobility that the theme was allowed to ring out with a call to arms in this concert hall built alongside the music room where Sir William Walton would pen his mighty fanfares.

Those for the Royal occasions and for the famous films of Shakespeare with Lawrence Olivier who would often holiday here with his close friends,the Waltons, seeking peace and anonymity from the Hollywoodian spotlight.

A mighty opening where Beethoven’s duel personality would contrast vehemence with tenderness with very little in between.These are variations that have long been associated with the learning of a classical piano technique as they are 32 variations posing different problems for the pianist more in vein with Brahms than most of Beethoven’s other works. In fact the other two essential works for aspiring young instrumentalists are the Handel Variations by Brahms and the Wanderer Fantasy of Schubert. They are all master works though and it is refreshing to be reminded of this as such masterly performances of the Beethoven and Schubert were allowed to unfold with the clarity and intelligent musicianship of this twenty one year old pianist.Variations that unwound with driving intensity always careful to follow Beethoven’s very precise markings.

The gentle opening of the first five variations from the alternating leggiermente patter,first from the right and then the left hands and finally together, leading to alternating rhythmic patterns before the first Beethovenian outburst of irascible impatience with the sixth variation. Gradually building up the tension and speeded up note values before dissolving quite abruptly to the major.Here Misha produced a sumptuous full string quartet sound as this produced the means for the next four variations .Double thirds played with clarity and etherial lightness and a play on rhythmic diversity before the beautifully mellifluous return to the minor.

Misha reserving the Beethovenian shock tactic for the eighteenth variation with its streams of notes shooting off like rockets leading to the dynamic rhythmic drive of the next four variations. An alternation of dynamism and delicacy brought us to the remarkable last two variations where Beethoven’s genius begins to shine through after a deftly hidden but nevertheless didactic display of musical exercises. A gentle cloud of C minor on which the music gradually builds to boiling point and the inevitable explosion before the gradually diminishing forces and the triumphant final bars that were played with aristocratic nobility before the final tongue in cheek whispered farewell. A remarkable performance where Misha was able to restore a work that even Beethoven did not particularly admire, to the concert hall,as did Emil Gilels and Annie Fischer in a glorious past era.

Two Chopin Mazurkas were played with the beguiling style of hypnotic rhythmic freedom and sense of dance .A haunting beauty of deep nostalgia with beautifully spun ornaments that unwound from his well oiled fingers like glittering springs but always incorporated into an architectural shape of subtle musicianship.

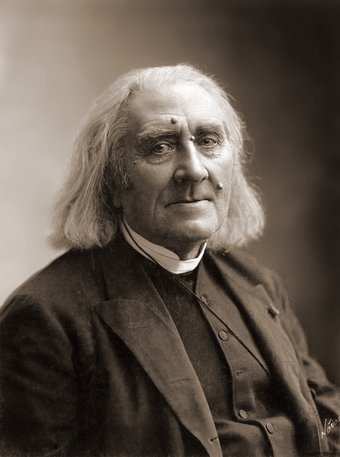

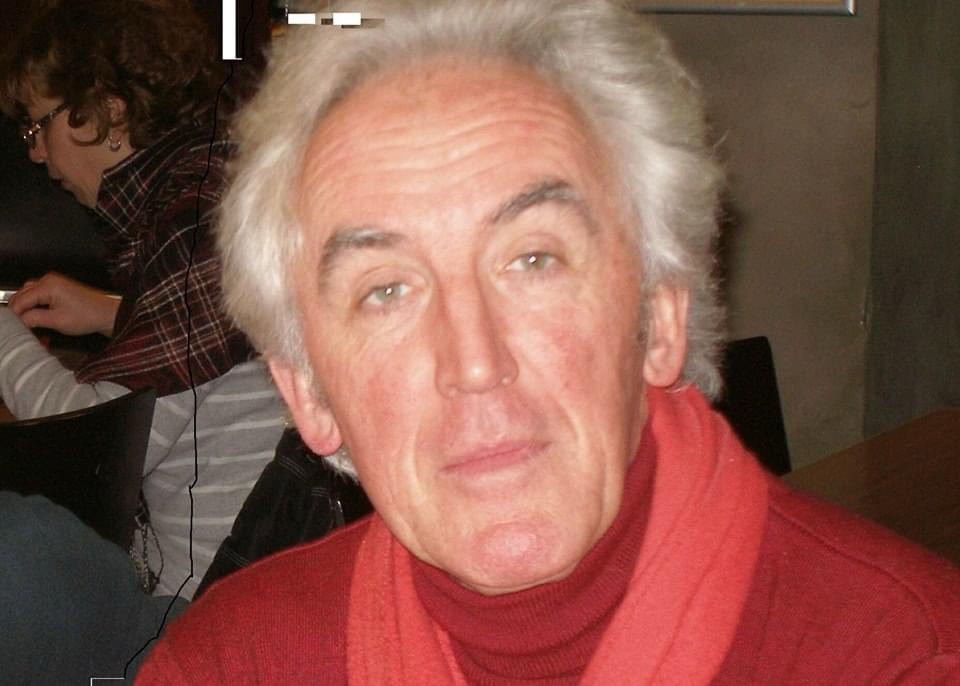

Liszt’s Bagatelle S.216 a was perhaps the unexpected highlight for me of the recital with Misha’s absolute clarity that could spin Liszt’s busy web of sounds with brilliance and teasing virtuosity.A remarkable rhythmic energy and very powerful vision of a work that can seem very ungrateful in lesser hands but today was made to sparkle with tantalising nonchalance and hypnotic insistence.The final remarkable bars just thrown off with masterly ease and was like a breath of fresh air before the sumptuous gloom and brooding intensity of Medtner.

And so on to a masterly performance of Medtner’s G minor Sonata op. 22. It was played with nobility and wild abandon and a kaleidoscope of colours .With its chameleonic changes of moods but, as with most of Medtner’s works, I find it hard to come to terms with his seemingly incoherent sense of line and direction. Misha played it with evident authority and total conviction I just wish I could have found the magic line that could bind these seemless streams of notes together into one architectural whole. I am so glad and grateful to be able to listen twice this weekend on Ischia to this work being performed by such an accomplished young virtuoso and will do my best to dispel my idea of Medtner as Rachmaninov without the tunes! It was the great Emil Gilels who only a year after the composers death began to include this very sonata in his programmes in the Soviet Union.There could be no greater commendation than that!

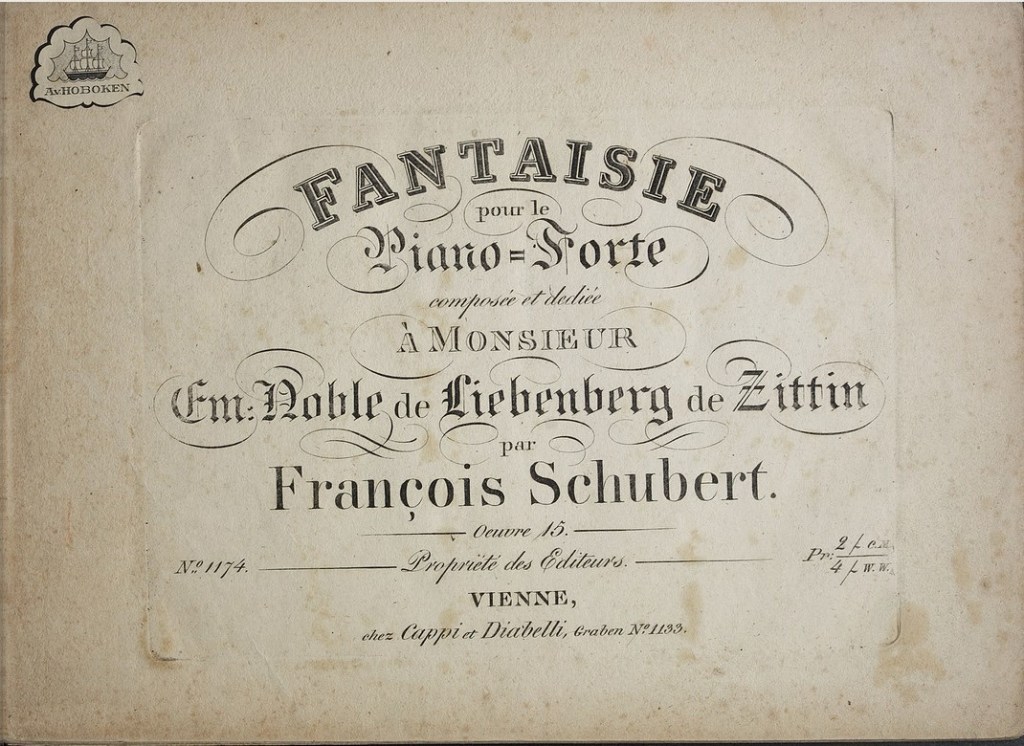

There was a dynamic Beethovenian drive to the opening of the ‘Wanderer Fantasy’ where again it was the remarkable clarity of his playing that illuminated the unusual virtuoso demands that Schubert makes of all those that dare play this extraordinarily revolutionary work. Playing of searing intensity where even Schubert’s usually seemless mellifluous outpourings are short lived as the music erupts with tempestuous fury. Extraordinary control and a dynamic range of sounds allowed Misha to sweep all before him as he lay the music exhausted to one side allowing the rhythmic impetus to gradually subside for the ‘Adagio ‘ of ‘Die Sonne dunkt mich hier so kalt’ of the song ‘Der Wanderer’. Beautifully played with full string quartet sound where every note had a poignant meaning as the theme unfolded to a series of variations of fantasy and beauty. Eventually the theme was allowed to float magically on a gently weaving accompaniment as seemless streams of jeux perlé golden sounds poured with exquisite delicacy from Misha’s sensitive fingers.Gradually building to a Beethovenian climax of unbridled dynamic drive before the etherial sounds that Schubert depicts with such genius allowing the music to disappear into the very depths of the keyboard. Masterly playing from this young pianist of vision and imagination.

The eruption of the Scherzo was as surprising as it was breathtaking in its audacity.Streams of notes spread over the entire keyboard that were mere waves of moving colours anchored by an imperious bass before the lyrical beauty, charm and hushed tones of the trio. Erupting again with demonic intensity the return of the Scherzo was played with breathtaking waves of notes of exhilaration and excitement where the silence after the final fortissimo chord was of expectancy and suspense. The opening declaration of the Fugue in the left hand was played with great authority and the whole movement played with a driving intensity and technical prowess that was overwhelming and quite breathtaking in its fearless abandon.A total control even in moments of red hot passion demonstrated Misha’s total mastery allied to impeccable musicianship and sense of style.His playing of Messiaen was masterly with a kaleidoscopic sense of colour that was quite extraordinarily poignant and with a pregnant beauty of searing intensity and heart rending meaning.A transcendental control of sound that was a revelation as indeed Messiaen can be if played with the same passionate intensity of a true believer.

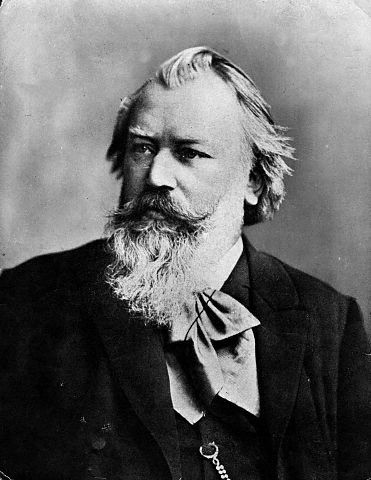

An encore of the deeply moving chorale prelude ‘Herzlich Tut mich verlangen’ by Brahms was written in his last days on this earth with thoughts of death and the hereafter deeply embedded in his soul.Intense poetic playing of great sensibility and ravishing beauty was the only way that this young poet of the keyboard knew how to thank such an attentive audience.

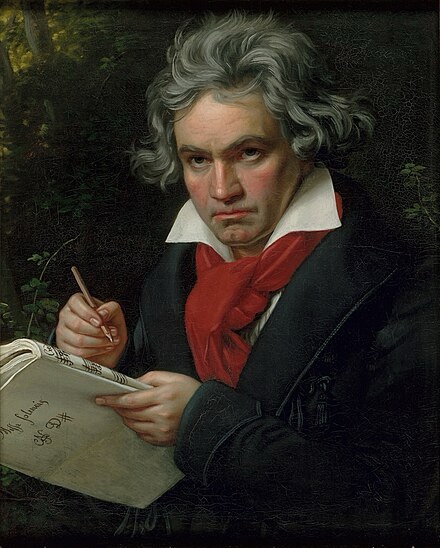

Ludwig van Beethoven 17 December 1770 Bonn – 26 March 1827 Vienna

32 Variations on an Original Theme in C minor, WoO 80 (German: 32 Variationen über ein eigenes Thema), for solo piano by WAS written in 1806.They have have been called “Beethoven’s most overt pianistic homage to the Baroque.” Receiving a favorable review in the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung (Leipzig) in 1807,it remains popular today especially amongst music students where together with Schubert Wanderer and Brahms Handel Variations is allows aspiring young musicians to acquire a classical technique and understand styles .Nevertheless, Beethoven did not see fit to assign it an opus number . It is said that later in his life he heard a friend practicing it and after listening for some time he said “Whose is that?” “Yours”, was the answer. “Mine? That piece of folly mine?” was his retort; “Oh, Beethoven, what an ass you were in those days!” Beethoven’s most overt pianistic homage to the Baroque, the 32 Variations on an original theme in C minor, WoO80, date from the end of 1806 (the year of the ‘Razumovsky’ quartets, the fourth symphony and the violin concerto) and were published the following year without dedication or opus number. The variations are an elaborate take on the traditional chaconne, a ceremonial triple-time dance over a ground bass that was popularized at the court of Louis XIV. (Bach’s monumental D minor violin ciaconna and Handel’s G major chaconne are famous examples, though it is doubtful that Beethoven would have known either.) Again, the music may have originated in the composer’s famous extemporizations.The poetic heart of the work lies in the five central major-keyed variations, beginning with No 12, closer in outline to the original theme than any of the previous variations.

The Fantasie in C major, Op. 15 ( D.760), popularly known as the Wanderer Fantasy, is a four-movement fantasy for solo piano composed by Schubert in 1822 when only 25 in a life that was tragically cut short by the age of 31.It is widely considered his most technically demanding composition for the piano and Schubert himself said “the devil may play it,” in reference to his own inability to do so properly.The whole work is based on one single basic motif from which all themes are developed. This motif is distilled from the theme of the second movement, which is a sequence of variations on a melody taken from the lied “Der Wanderer”, which Schubert wrote in 1816. It is from this that the work’s popular name is derived.The four movements are played without a break. After the first movement Allegro con fuoco ma non troppo in C major and the second movement Adagio (which begins in C-sharp minor and ends in E major), follow a scherzo presto in A-flat major and the technically transcendental finale, which starts in fugato returning to the key of C major and becomes more and more virtuosic as it moves toward its thunderous conclusion.Liszt was fascinated by the Wanderer Fantasy, transcribing it for piano and orchestra (S.366) and two pianos (S.653). He additionally edited the original score and added some various interpretations in ossia and made a complete rearrangement of the final movement (S.565a).I remember a recent lesson I had listened to of Elisso Virsaladze in which I was struck by the vehemence of the Wanderer Fantasy and the ragged corners that we are more used to in a Beethoven almost twice Schubert’s age .It made me wonder about the maturity of the 25 year old Schubert and could he have had a premonition that his life was to be curtailed only six years later.We are used to the mellifluous Schubert of rounded corners and seemless streams of melodic invention.But surely in the final three sonatas written in the last months of his life the A major and C minor start with a call to arms and only in the last B flat sonata do we arrive at the peace and tranquility that Beethoven was to find too in his last sonata.But the deep rumblings in the bass in Schubert’s last sonata give food for thought that his life was not all sweetness and light.I remember Richter’s long tribulation in the recording studio to put on record as near definitive version as possible of the Wanderer Fantasy with the help of the pianist and musicologist Paul Badura Skoda.

Schubert’s Wanderer Fantasy and the challenges of an Urtext edition

At the heart of ‘Wanderer’ is a song he wrote in 1816 based on a text by Georg Philipp Schmidt von Lübeck (1766 – 1849). In the song, the wander seeks happiness, but cannot find it anywhere – when he sighs ‘where?’ the answer comes back, ‘There, where you are not, is your happiness.’ Schmidt von Lübeck’s original title, Des Fremdlings Abendlied (The Stranger’s Evening Song) places it in greater perspective – this is the question of every stranger looking for something that may not exist where he’s seeking it.

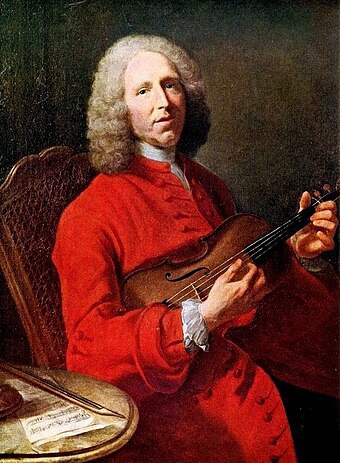

The work as a whole is the product of experimentation on Schubert’s part – he links the entire work in four movements through a set of similar rhythms and in the last movement, wraps the whole structure around to bring in elements of the first movement. The work is a challenge for the pianist, and both its virtuosity and structure fascinated the Romantics (most importantly Liszt)for decades.The Fantasy was commissioned by a wealthy amateur pianist, Emanuel Karl Liebenberg, a pupil of Hummel ( who had been a pupil of Mozart ) Schubert recognized that he had written a work that makes greater technical demands on the performer than did the two piano sonatas he wrote after this piece was completed.

Franz Liszt (1811–86)

Bagatelle without tonality, S.261a

At a later stage in his life Liszt experimented with “forbidden” things such as parallel 5ths in the “Csárdás macabre”and atonality in the Bagatelle sans tonality (“Bagatelle without Tonality”). Pieces like the “2nd Mephisto-Waltz” are unconventional because of their numerous repetitions of short motives. Also showing experimental characteristics are the Via crucis of 1878, as well as Unstern!, Nuages Gris and the two works entitled La lugubre gondola of the 1880s.

Bagatelle sans tonalité was written by in 1885. The manuscript bears the title “Fourth Mephisto Waltz”and may have been intended to replace the piece now known as the Fourth Mephisto Waltz when it appeared Liszt would not be able to finish it; the phrase Bagatelle ohne Tonart actually appears as a subtitle on the front page of the manuscript.

While it is not especially dissonant, it is extremely chromatic becoming what Liszt’s contemporary Fétis called “omnitonic”in that it lacks any definite feeling for a tonal center.Like the Fourth Mephisto Waltz, however, it was not published until 1955.Written in waltz form,the Bagatelle remains one of Liszt’s most adventurous experiments in pushing beyond the bounds of tonality, concluding with an upward rush of diminished sevenths .

Nikolai Karlovich Medtner 5 January 1880, Moscow-13 November 1951 (aged 71) Golders Green England

Performed by Prokofiev and Horowitz, recorded by Moiseiwitsch and Gilels, this one-movement work, completed in 1910, is the Medtner sonata which is the best known of his 14 Sonatas ,for its powerful drama strongly appealing to the emotions but also its coherence as a perfect organic whole on a large scale. As Heinrich Neuhaus wrote: ‘The sonata’s trajectory is felt from the first to the last note as one uninterrupted line.’ All the thematic material is integrated and never ceases to grow organically right up to the massive coda, which is a true culmination in both synthesizing and intensifying what has gone before, with two pages of characteristically Medtnerian contrasting rhythms in the right and left hands. The sonata’s daring tonal scheme—a rising sequence of alternately minor and major thirds—is further evidence of Medtner’s originality in his use of traditional musical language and design.

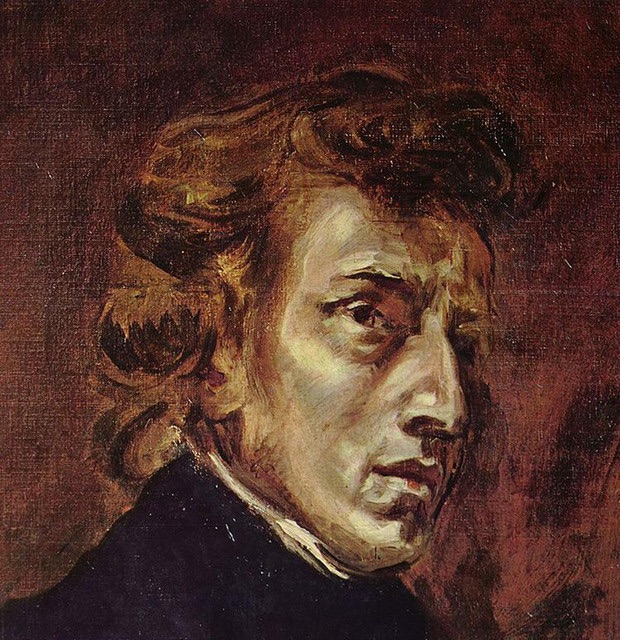

Fryderyk Franciszek Chopin;1 March 1810 – 17 October

Over the years 1825–1849, Chopin wrote at least 59 compositions for piano called Mazurkas referring to one of the traditional Polish dances

- 58 have been published

- 45 during Chopin’s lifetime, of which 41 have opus numbers (with the remaining four works being two early mazurkas from 1826 and the famous “Notre Temps” and “Émile Gaillard” mazurkas that were published individually in 1841)

- 13 posthumously, of which 8 have posthumous opus numbers (specifically, Opp. 67 & 68)

- 11 further mazurkas are known whose manuscripts are either in private hands (2) or untraced (at least 9).

The serial numbering of the 58 published mazurkas normally goes only up to 51. The remaining 7 are referred to by their key or catalogue number.

Chopin while he used the traditional mazurka as his model, he was able to transform his mazurkas into an entirely new genre, one that became known as a “Chopin genre”.

In 1852, three years after Chopin’s death, Liszt published a piece about Chopin’s mazurkas, saying that Chopin had been directly influenced by Polish national music to compose his mazurkas. Liszt also provided descriptions of specific dance scenes, which were not completely accurate, but were “a way to raise the status of these works [mazurkas].”While Liszt’s claim was inaccurate, the actions of scholars who read his writing proved to be more disastrous. When reading Liszt’s work, scholars interpreted the word “national” as “folk,” creating the “longest standing myth in Chopin criticism—the myth that Chopin’s mazurkas are national works rooted in an authentic Polish-folk music tradition.”In fact, the most likely explanation for Chopin’s influence is the national music he was hearing as a young man in urban areas of Poland, such as Warsaw.

After scholars created this myth, they furthered it through their own writings in different ways. Some picked specific mazurkas that they could apply to a point they were trying to make in support of Chopin’s direct connection with folk music. Others simply made generalizations so that their claims of this connection would make sense. In all cases, since these writers were well-respected and carried weight in the scholarly community, people accepted their suggestions as truth, which allowed the myth to grow. However, in 1921, Béla Bartok published an essay in which he said that Chopin “had not known authentic Polish folk music.”By the time of his death in 1945, Bartók was a very well known and respected composer, as well as a prominent expert on folk music, so his opinion and his writing carried a great deal of weight. Bartók suggested that Chopin instead had been influenced by national, and not folk music.Schumann described Chopin Mazurkas as ‘Canons covered in flowers’.The Op. 24 mazurkas were published in 1836, when the composer was 26

Mazurka in C major, Op. 24 No. 2

The second mazurka marked Allegro non troppo opening with a quiet alternation of C and G major sotto voce chords.

Mazurka in B-flat minor, Op. 24 No. 4

The fourth mazurka of the set is in B flat minor but ends on the dominant note (F) alone

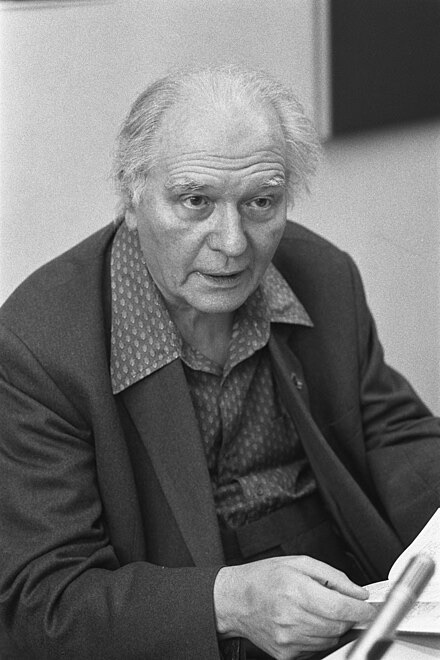

Olivier Eugène Prosper Charles Messiaen 10 December 1908 – 27 April 1992

Olivier Messiaen was born on 10 December 1908 in Avignon into a literary family. His father was an eminent translator of English literature and his mother, Cécile Sauvage, was a published poet. Messiaen displayed a precocious musical talent from an early age, being accepted by the time he was eleven into the Paris Conservatoire where he studied piano, composition and organ. After graduation, he served as organist at the Église de la Sainte-Trinité in Paris from 1931 until his death, and his own contribution to the organ repertoire is arguably greater than that of any other composer since Bach.

In 1932 Messiaen married the violinist Claire Delbos and they had a son five years later. During World War II, he was captured while serving as a medical auxiliary and held as a prisoner of war at Görlitz in Silesia. It was there that he wrote one of his most famous works, the Quatuor pour le fin de temps (Quartet for the End of Time), which was first performed in the camp by four of the prisoners. After his release in 1941, Messiaen returned to Paris and took up a professorship at the Conservatoire. Towards the end of war, Claire developed mental health problems following an operation. Her condition worsened steadily and she was eventually hospitalised until her death in 1959.

Messiaen had been fascinated by birdsong since adolescence; he once described birds as ‘probably the greatest musicians to inhabit our planet’. In 1953 he began travelling around France, meticulously notating different birdsong and using it in his music. By the 1960s as his growing international reputation was taking him further afield (including Japan, Iran, Argentina and Australia), he extended concert trips to further his birdsong research, often accompanied by his second wife, the pianist Yvonne Loriod, whom he had married in 1961.

Messiaen wrote Vingt regards sur l’Enfant-Jésus between March and September 1944. The origins of the work lay in a request from the writer Maurice Toesca for twelve short piano pieces to accompany his poetry on the Nativity in a radio production. However, Messiaen strayed extensively from his brief to produce his largest, most ambitious work to date. Vingt Regards places enormous technical and musical demands on the pianist; it is a work of great contrasts, ranging from the aching tenderness of Regard de la Vierge, through the awesome mystery of L’échange (referring to the divine trade whereby God became man in order that men could become gods) to the primal brutality of Par Lui tout a éte fait. Today, the work is rarely heard in full, though shorter sections or individual movements are often included in recital programmes.

The twenty Regards, variously translated as ‘gazes’, ‘aspects’ or ‘glances’, are twenty contemplations on the Infant Jesus, seen from different perspectives; in other words the Regard du Père represents a contemplation on Jesus by God the Father, Regard de l’étoile by the star, Regard de la Vierge by the Virgin,and so on.Vingt Regards had its première on 26 March 1945 at the Salle Gaveau in Paris with Yvonne Loriod, the work’s dedicatee, who was only twenty-one years old at the time. The event divided critical opinion, with one critic paying homage to ‘a very great musician who proclaims himself triumphantly in the Vingt Regards sur l’Enfant-Jésus’, while another vehemently asserted that the composer was ‘attempting to translate the sublime utterances of the Apocalypse through muddled literature and music, smelling of the hair-shirt, in which it is impossible to detect either any usefulness or pleasure’. Over half a century later, the work has stood the test of time and is regarded today as a keystone in twentieth-century piano repertoire.Le Baiser is the 15th of 20

Olivier Messiaen (1908–1992)

Vingt Regards sur l’Enfant-Jésus

- Regard du Père (Gaze of the Father)

- Regard de l’étoile (Gaze of the Star)

- L’échange (The Exchange)

- Regard de la Vierge (Gaze of the Virgin)

- Regard du Fils sur le Fils (Gaze of the Son upon the Son)

- Par Lui tout a été fait (By Him Everything was Created)

- Regard de la Croix (Gaze of the Cross)

- Regard des hauteurs (Gaze of the Heights)

- Regards du Temps (Gaze of Time)

- Regard de l’Esprit de joie (Gaze of the Spirit of Joy)

- Première communion de la Vierge (First Communion of the Virgin)

- La parole toute puissante (The All-Powerful Word)

- Noël (Christmas)

- Regard des Anges (Gaze of the Angels)

- Le baiser de l’Enfant-Jésus (The Kiss of the Infant Jesus)

- Regard des prophètes, des bergers et des Mages (Gaze of the Prophets, the Shepherds and the Magi)

- Regard du silence (Gaze of Silence)

- Regard de l’Onction terrible (Gaze of the Great Anointment)

- Je dors, mais mon cœur veille (I Sleep, but my Heart is Awake)

- Regard de l’Eglise d’amour (Gaze of the Church of Love)

7 May 1833 Hamburg 3 April 1897 (aged 63) Vienna

Eleven Chorale Preludes, Op. 122, is a collection of works for organ by Johannes Brahms , written in 1896, at the end of the composer’s life, immediately after the death of his beloved friend, Clara Schumann, published posthumously in 1902. They are based on verses of nine Lutheran chorales, two of them set twice, and are relatively short, compact miniatures. They were the last compositions Brahms ever wrote, composed around the time that he became aware of the cancer that would ultimately prove fatal; thus the final piece is, appropriately enough, a second setting of “O Welt, ich muß dich lassen.” Brahms was prepared for death and even longing for it . It is no coincidence that the text to most of the chorales are concerned with death and the hereafter Busoni arranged the six most pianistic for piano in 1897 and they are 4/5/8/9/10/11.

- Mein Jesu, der du mich (My Jesus. who [chose] me) in E minor

- Herzliebster Jesu,was hastily du verbrochen (O dearest Jesu) in G minor

- O Welt, ich muß dich lassen (O world, I must leave you) in F major

- Herzlich tut mich erfreuen (My heart is filled) in D major

- Scmucke dich,o liebe Seele (Deck yourself, O dear soul) in E major

- O wie selig seid ihr doch, ihr Frommen (O how blessed are you pious ones)in D minor

- O Gott, du frommer Gott (O God, you faithful God) in A minor

- Es ist e in Ros’entsprungen (It is an upspringing rose) in F major

- Herzlich tut mich verlagen (I am heartily longing) in A minor

- Herzlich tut mich verlangen (second setting) in A minor

- O Welt, ich muß dich lassen (second setting) in F major

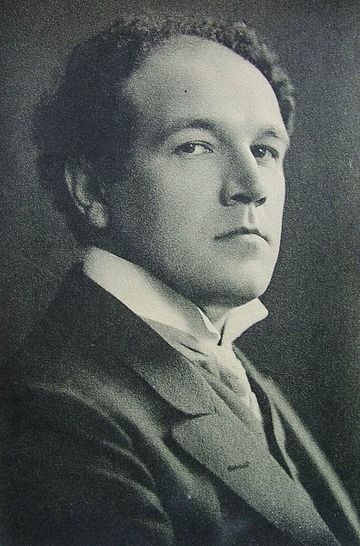

Misha Kaploukhii was born in 2002 and is an alumnus of the Moscow Gnessin College of Music, where he studied in the piano class of Mikhail Egiazarian. Misha is currently studying at the Royal College of Music; he is an RCM and ABRSM award holder generously supported by Robert Turnbull Piano Foundation and Talent Unlimited charity studying for a Bachelor of Music with Professor Ian Jones.

Misha has gained inspiration from lessons and masterclasses with musicians such as Claudio Martínez Mehner, Dmitri Bashkirov, Jerome Lowenthal and Konstantin Lifschitz. He has performed with orchestras around the world including his recent debut in Cadogan Hall with the Rachmaninoff 1st Piano Concerto. How repertoire includes a wide range of solo and chamber music. Recently, Misha has won prizes in the RCM concerto competition (playing Liszt’s 2nd Piano Concerto) and in the International Ettlingen Piano Competition.”

MISHA KAPLOUKHII winner of the Sheepdrove Piano Competition today

Many congratulations you can hear him also at Cadogan Hall next February 19th playing Brahms Second Piano Concerto also at the Royal College of Music on Friday 24th at 11.50 for his Graduation Recital ( free entry)

A wonderful opportunity to hear the best international piano students drawn from all the major UK conservatoires – and to cast your vote for the audience prize!

Now celebrating its 15th Anniversary, this notable competition, established by the Sheepdrove Trust, is open to candidates aged 26 and under from the eight major UK music colleges, and attracts young pianists of the highest standard from around the world. Today’s competition, which this year has an emphasis on Chopin, features four shortlisted finalists and takes place in the tranquil setting of Sheepdrove on the Lambourn Downs. The overall winner will perform a solo recital in the Corn Exchange on Monday 20 May as part of the Festival’s popular Young Artists Lunchtime Recital Series.

Prizes

1st Prize: The Kindersley Prize of £3,000. Misha Kaploukhii

2nd Prize: £1,500 donated by Greenham Trust. Kasparas Mikuzis

3rd Prize: £750 donated by the Friends of NSF. Yuxuan Zhao

4th Prize: £500 donated by an anonymous donor.Max Artemenko

Audience Prize: £250 donated by an anonymous donor Misha Kaploukhii

The Robert Turnbull Piano Foundation Prize Angeliki Giannopoulow and Xizong Chen

Jury

Rupert Christiansen

Mark Eynon

Mikhail Kazakevich

Elena Vorotko

David Whelton

Some superb playing if rather unusual attire.One could say the same about Yuja Wang but it is their playing that astonishes and astounds.

Misha Kaploukhii’s graduation recital today kissing the Enfant Jesu a breathtaking goodbye as only Messiaen knew how.

After an all or nothing performance of Schubert’s Wanderer Fantasy ,a monumental Medtner G minor Sonata and even a Bukovina Prelude it is hardly surprising that last Sunday saw him winner of the coveted Sheepdrove Competition and considered the finest artist from all the eight major conservatories of the land.