A quite breathtaking recital from one of the finest young pianists of his generation .Not only a pianist but also a composer and it is this that comes across in all that he does. A sense of architectural understanding whether the complex sound world of Hough or the rugged Hungarian dance idiom of Bartok or the ravishing world of Schumann and even the gem of a Mendelssohn Song without words .

An eclectic multifaceted pianist who is about to play the Busoni Piano Concerto and has just played Rzewski’s marathon variations in Germany (that awaits London at the Wigmore Hall in October) or playing his own theme and variations written as an engagement present for his future wife. Piano genius I think is not too exaggerated a word in this case …………….Hats off, dear Emanuil ,as Hugh so rightly said the best recital ever at Perivale today

As Emanuil said programming contemporary music is a way of keeping creativity alive and so he chose to open his programme with the sparse sounds of Stephen Hough’s ‘Trinitas’ .Emanuil is not only a great pianist but a complete thinking musician of great humility and sensitivity. Listening to this contemporary work one is given a completely different picture of a pianist well known for his sense of late romantic style of piano playing of a lost age. Stephen has brought back into the concert hall works that were long not considered important enough for the concert stage in these modern times where a rigid adhesion to the score can also kill the very creative impulse of the composer when the ink was still wet on the page.Listening to the sparse sounds of this Sonata just underlines what Emanuil said about recreating music with a freshness and not just painting a picture of times past.This explains of course why Stephen Hough’s performances of such miniatures by Delibes,Chaminade or Mompou are of ravishing beauty that with such refreshing innocence he can turn baubles into gems. Cherkassky too ,who was a great admirer of the young Hough, lived by the motto :’je joue,je sens ,je trasmet.’ Mitsuko Uchida in refusing to allow photos or recordings of her live recitals forcefully exclaimed as only she could ,that a performance should remain in the memory as a thing of beauty and not just end up being something stale on a printed page. Last but certainly not least was Rubinstein who would add the four Mazurkas op.50 written for him by Szymanowski as a sorbet in the midst of a sumptuous feast of Chopin.

And so it was today that everything that Emanuil played was with a spontaneity and freshness that made for a bond of mutual creativity between the audience and the performer.There was the dramatic opening of sparse sounds of stark nakedness as there was also an elegance and fluidity to these sounds that were hypnotic and captivating. Great rhythmic energy in the middle movement that was also played with astonishing clarity and agility.Suddenly distant sounds reminiscent of Messiaen could be heard in the far distance. There was even a recognisable melody in the midst of a continuous flow of dynamic note spinning. Long vibrant sounds with whispered reverberations on high where Chopin’s 3rd Scherzo came to mind as a chorale is heard with such regal purpose. Colourless sounds too of beauty but without a specific voice as they sounded like dead wooden interjections. The work ending with the same sparse sounds as the opening where at last peace is allowed to reign sovereign again.Emanuil created a world of kaleidoscopic sounds but managed to steer us through unknown waters with the simplicity and astonishing clarity of a convinced musician.

There was a startling rhythmic energy and above all a clarity that I have not heard since Andor Foldes or Geza Anda. A great personality that took us by storm alternating with beguiling beseeching sounds but always with a burning hypnotic intensity.A slow movement that was a deep siren of long drawn out sounds, like the slow movements of his concertos, where there is a religious intensity of poignant meaning.The dynamic drive he brought to the Allegro finale was of astonishing virtuosity with a flexibility that was like stretching an elastic band that seemed to have an eel like vitality of it’s own.

With these Symphonic Studies our eclectic musician had decided to incorporate some of the differences from the first 1837 edition that the composer had excluded from his second in 1852. Principally in the Finale where the repetitive nature of the ‘Allegro brillante’ was relieved by glimpses of melodic oasis’s amidst such a continuously driven stream of notes.There was a beautiful simplicity to the first three variations or studies where the theme was allowed to unfold with unadorned beauty.The variations were allowed to flow so naturally with a scrupulous attention to detail but without ever interrupting the continual evolution as one variations flowed so easily into the next. There was astonishing ‘fingerfertigkeit’ in the fleeting butterfly third study where the melodic line was allowed to emerge rather that being intentionally projected . It was at this point that Emanuil had decided to allow the first three of the five posthumous studies to take part in the proceedings. Some pianist choose not to include these five posthumous studies that were first published by Brahms after Schumann’s untimely death in an asylum. Others add them all after the ‘Gothic cathedral’ (to quote Guido Agosti) variation 7 ( study n. 8) .

Emanuil found just the right place for the swirling dramatic sounds of this first study that contrasted so well with the utter simplicity of the second that gradually works itself into a series of mysterious agitated sounds on which the theme suddenly appears naked on high like a mystical apparition.There was a wonderful sense of balance to the third that only a true musician could have found with such simplicity. At this point Emanuil rejoined the original version with the fourth study or 3rd variation where he shaped the chords with wonderfully crisp but varied sounds subtly phrased as they became transformed into the fleeting lightness of the fifth study or fourth variation.Rarely have I heard this dotted scherzando rhythm played with such clarity and melodic shape. There was a passionate outpouring to the fifth variation without any rhetorical exaggerations as is so often the case in lesser hands, leading to a sixth variation of dynamic drive.The great ‘Gothic Cathedral’ was played with disarming simplicity and with contrasts in phrasing that were breathtaking for their understanding and poignant significance.It was at this point that Emanuil added the fourth and fifth posthumous studies creating a beauty of glowing fluidity with Schumann’s sounds of searing beauty. The spell was broken with the Mendelssohnian chords of fleeting lightness and transcendental difficulty thrown off by this virtuoso with a mastery of aristocratic class where the music was always sovereign.The tenth study ( eighth variation ) erupted with energy and drive but always shaped into phrases with a sense of direction and purpose.The eleventh study was played with disarming simplicity as this Chopinesque nocturne was allowed to flow with a ravishing sense of balance.The ‘Allegro brillante’ finale was played with a driving forward movement and even the glimpses left from the first edition could not quel the accumulation of excitement and aristocratic grandeur of one of the pinnacles of the piano repertoire.

An ovation as rarely seen in Perivale and our host unusually lost for words, was greeted by the Mendelssohn Song without Words in E major op 30 n. 3 .Just one page but there was magic in the air that this young piano genius had created with music making as rarely witnessed before at St Mary’s in over 800 concerts.

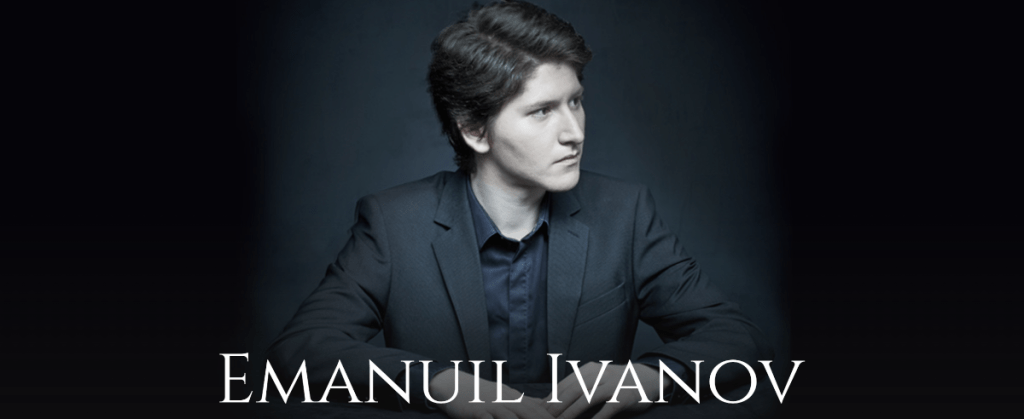

Emanuil Ivanov attracted international attention after receiving the First prize at the 2019 Ferruccio Busoni Piano Competition in Italy. This achievement was followed by concert engagements in some of the world’s most prestigious halls including Teatro alla Scala in Milan and Herculessaal in Munich. He was born in 1998 in the town of Pazardzhik, Bulgaria. From an early age he demonstrated a keen interest and love for music. He started piano lessons with Galina Daskalova in his hometown around the age of seven. He later studied in and graduated from the Bertolt Brecht language high school in Pazardzhik. Ivanov studied with renowned bulgarian pianist Atanas Kurtev from 2013 to 2018. He is currently studying on a full scholarship at the Royal Birmingham Conservatoire under the tutelage of Pascal Nemirovski and Anthony Hewitt.

Emanuil Ivanov has won prizes in competitions such as “Alessandro Casagrande”, “Scriabin-Rachmaninoff”, “Liszt-Bartok”, “Young virtuosos” and “Jeunesses International Music Competition Dinu Lipatti”. He was also awarded the honorary Crystal lyre and the Young Musician of the Year Award – some of the most prestigious awards in Bulgaria. In 2022 he received the honorary Silver Medal of the London Musicians’ Company and later in the same year became a recipient of the Carnwath Piano Scholarship.

In February 2021, at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, Ivanov performed a solo recital in Milan’s famous Teatro alla Scala. The concert was live-streamed online and is a major highlight in the artist’s career. He has performed at many festivals in Bulgaria and has also given solo recitals in Japan, France, Italy, Germany, Austria, Cyprus, South Africa, the United Kingdom and Poland. He has played with leading orchestras in Bulgaria and Italy.

Robert Schumann in 1839

Born

8 June 1810

Zwickau,Saxony

Died

29 July 1856 (aged 46)

Bonn , Rhine Province, Prussia

The Symphonic Studies Op. 13, began in 1834 as a theme and sixteen variations on a theme by Baron von Fricken, plus a further variation on an entirely different theme by Heinrich Marschner.The first edition in 1837 carried an annotation that the tune was “the composition of an amateur”: this referred to the origin of the theme, which had been sent to Schumann by Baron von Fricken, guardian of Ernestine von Fricken, the Estrella of his Carnaval op. 9. The baron, an amateur musician, had used the melody in a Theme with Variations for flute. Schumann had been engaged to Ernestine in 1834, only to break abruptly with her the year after. An autobiographical element is thus interwoven in the genesis of the Études symphoniques (as in that of many other works of Schumann’s).Of the sixteen variations Schumann composed on Fricken’s theme, only eleven were published by him. (An early version, completed between 1834 and January 1835, contained twelve movements). The final, twelfth, published étude was a variation on the theme from the Romance Du stolzes England freue dich(Proud England, rejoice!), from Heinrich Marschner’s opera Der Templer und die Judin based on Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe (as a tribute to Schumann’s English friend, William Sterndale Bennett to whom it is dedicated )The earlier Fricken theme occasionally appears briefly during this étude. The work was first published in 1837 as XII Études Symphoniques. Only nine of the twelve études were specifically designated as variations. The entire work was dedicated to Schumann’s English friend, the pianist and composer, and Bennett played the piece frequently in England to great acclaim, but Schumann thought it was unsuitable for public performance and advised his wife Clara not to play it.The highly virtuosic demands of the piano writing are frequently aimed not merely at effect but at clarification of the polyphonic complexity and at delving more deeply into keyboard experimentation.

- Theme – Andante [C♯ minor]

- Etude I (Variation 1) – Un poco più vivo [C♯ minor]

- Etude II (Variation 2) – Andante [C♯ minor]

- Etude III – Vivace [E Major]

- Etude IV (Variation 3) – Allegro marcato [C♯ minor]

- Etude V (Variation 4) – Scherzando [C♯ minor]

- Etude VI (Variation 5) – Agitato [C♯ minor]

- Etude VII (Variation 6) – Allegro molto [E Major]

- Etude VIII (Variation 7) – Sempre marcatissimo [C♯ minor]

- Etude IX – Presto possibile [C♯ minor]

- Etude X (Variation 8) – Allegro con energia [C♯ minor]

- Etude XI (Variation 9) – Andante espressivo [G♯ minor]

- Etude XII (Finale) – Allegro brillante (based on Marschner’s theme) [D♭ Major]

On republishing the set in 1890, Johannes Brahms restored the five variations that had been cut by Schumann. These are now often played, but in positions within the cycle that vary somewhat with each performance; there are now twelve variations and these five so-called “posthumous” variations which exist as a supplement.

The five posthumously published sections (all based on Fricken’s theme) are:

- Variation I – Andante, Tempo del tema

- Variation II – Meno mosso

- Variation III – Allegro

- Variation IV – Allegretto

- Variation V – Moderato.

- Moderato.

In 1834, Schumann fell in love with Ernestine von Fricken, a piano student of Friedrich Wieck, and for a time they seemed destined to marry. The relationship did not last—Schumann got cold feet after he learned that she had been born out of wedlock—but it inspired some notable music. Carnaval, Op. 9, a set of character pieces for piano, is based on a four-note motive derived from the name of Ernestine’s home town. The Etudes symphoniques, Op. 13, are variations on a theme by Ernestine’s father, Ignaz Ferdinand von Fricken, a nobleman and amateur composer. Of course, Schumann eventually transferred his affections to Clara Wieck, and it was she who gave the first performance of the Etudes symphoniques, in 1837. The piece was published by Haslinger that same year, with a dedication to the English composer William Sterndale Bennett rather than to Ernestine. A revised version appeared in 1852.

Our manuscript is a sketch that includes the theme and variations 1, 2, 5, 10, 12, as well as five others that were not published until 1873, in an appendix edited by none other than Johannes Brahms. It formerly belonged to Alice Tully (1902–1993), the philanthropist whose name graces a concert hall in Lincoln Center. She gave it to Vladimir Horowitz (who counted Schumann’s music among his many specialties in the piano repertoire), and two years after his death, his widow Wanda Toscanini Horowitz donated it to Yale. The other principal manuscript source for this piece belongs to the library of the Royal Museum of Mariemont, in Belgium.

Hough’s Piano Sonata III, “Trinitas”, commissioned by The Tablet, the second-oldest surviving weekly journal in Britain after The Spectator. The Tablet is a journal which combines loyalty to the Catholic Church with an irrepressible inquisitiveness, and thus its special connection with Stephen Hough seems especially appropriate.

In his new Sonata, Hough explores the 12-note row, the compositional technique of “serialism”. It is a form of musical dogma, and Hough cleverly links this back to The Tablet and Catholicism by scoring the work in three movements and subtitling it “Trinitas”, Latin for “Trinity”, another dogma, the theological ordering of numbers. To guide the listener, each movement is helpfully described (“bold, stark”, “punchy, jazzy” and “majestic, proud”).The middle movement, rhythmically vibrant with its lively syncopations, rapid tinkling notes high in the treble and colourful note clusters, was redolent of Messiaen, another devout Catholic, while its virtuosity referenced Liszt. The final movement, with rich textures and majesty, quotes a familiar hymn tune (Nicea, a setting of the Trinitarian text “Holy, Holy, Holy”) which is disrupted by discordant sounds towards its conclusion. Yet despite the dogma and metaphysics, this work was accessible and at times witty, quirky and playful, and it is exciting to know that such variety and imagination is readily available for other pianists to tackle and enjoy.

The Piano Sonata, BB 88, Sz. 80, is by Bela Bartok was composed in June 1926. 1926 is known to musicologists as Bartók’s “piano year”, when he underwent a creative shift in part from Beethovenian intensity to a more Bachian craftsmanship

The work is in three movements, with the following tempo indications:

- Allegro moderato

- Sostenuto e pesante

- Allegro molto

It is tonal but highly dissonant (and has no key signature ) using the piano in a percussive fashion with erratic time signatures Underneath clusters of repeated notes, the melody is folklike. Each movement has a classical structure overall, in character with Bartók’s frequent use of classical forms as vehicles for his most advanced thinking. Musicologist Halsey Stevens finds in the work early forms of many stylistic traits that became more fully developed in Bartók’s “golden age”, 1934–1940.

Bartók wrote Dittának, Budapesten, 1926, jun. at the end of the score, dedicating it to Ditta Pasztory- Bartok , his second wife. A performance generally lasts around 15 minutes. Bartók wrote the duration as around 12 minutes and 30 seconds on the score.

Bartok wrote this piece with an Imperial Bosendorfer in mind, which has extra keys in the bass (97 keys in total). The second movement calls for these keys to be used (to play G sharp and F0).

Bartók had previously written a piano sonata in 1896, which is little known.