Beethoven Sonata n. 8 in do minore op. 13 “Patetica”

Schönberg 3 Klavierstücke op. 11

Beethoven Sonata n. 2 in la maggiore op. 2 n. 2

Schönberg 3 Klavierstücke (1894)

Schönberg 6 Kleine Klavierstücke op. 19

Beethoven Sonata n. 23 in fa minore op. 57 “Appassionata”

Emanuel Ax in Rome to pay homage to Maurizio Pollini on the day when the much loved pianist should have given his annual recital for the Accademia di Santa Cecilia . The tribute that he put into words at the end of two hours of pure whispered magic was crowned by a performance of one of the nocturnes that were particularly associated with Pollini. Rubinstein made the Chopin Nocturne in D flat op 27 n.2 his own as Pollini did with its twin op 27 n.1 .

Op.27 n.2 is full of luminosity and ravishing Bel Canto with a seemless melodic line floated on a cloud of velvet whereas op 27 n.1 is much more restless and darker with its Debussy like opening creating sounds full of mystery and foreboding. It was here that the wondrous sounds and kaleidoscope of unforced whispered colours created the same atmosphere that Pollini would often do in the half century of performances that Emanuel Ax movingly described later in a short speech in well prepared Italian.The beauty of sound and selfless identification with the music had created a spell from the very first notes of a typical Pollini programme of Beethoven and Schonberg.

The ‘Pathétique’ sonata was as though hearing it for the first time such was the palette of sounds where the notes were not projected out to this vast hall but the audience were drawn in to him.By some magic,called consummate artistry, he managed to play with whispered sounds of luminosity and beauty which arrived in the nearest and farthest seats with the same intensity.A singer with a diaphragm is an art that is rapidly being forgotten as more and more artists rely on acoustically assisted sound to help them in the vast halls that are springing up throughout the world . But the few great artists,one of which is certainly Emanuel Ax ,that still grace the concert halls have cultivated this art as part of their genes with a lifetime of sharing music with audiences worldwide. It is nice to note that Emanuel Ax was much admired at the first Rubinstein competition where the great maestro awarded him his Gold Medal. Much as Rubinstein years earlier had also awarded an 18 year old Pollini the Gold Medal at the Chopin Competition in Warsaw.Rubinstein famously and with his great generosity exclaimed that this young man played better than any of them on the jury!

And so Maurizio Pollini was to demonstrate in a career that was to span over seventy years.Pollini ,like Guido Agosti and Busoni before that treated the score with the reverence that it demanded with a selfless dedication where they became the medium through which the music still wet on the page could be transmitted and shared. Audiences that clamoured to be rid of showmen who in the early part of the last century would take the composer’s notes as a means to show off their virtuosity and in the case of pianists like De Pachmann ,their own personality. I remember a review forty years ago of Cherkassky in Milan where he had been asked to play a programme of scintillating show piece transcriptions :’Juggler of the notes’ was the title of the review in the Corriere della Sera. Cherkassky like Volodos vowed never to deviate from the programmes that they had decided on for the season.

It was very much Pollini who had created this new path for performances of absolute fidelity to the score and the composers wishes.Pollini would be an advocate of living composers too such as Nono and Stockhausen.And so tonight ,on the same evening that Pollini should have appeared, there could be no more fitting way to pay homage to his genius than with a programme of the ‘old’ and the ‘new’.

Beethoven alternating with Schonberg ,where one illuminated the other and made one listen afresh to works that we have heard almost too many times. The Beethoven was freshly minted with sounds that truly spoke as they were not percussive but full of subtle colour .The language of Music which allows us to enter a world where words are just not enough!

Beethoven op 13 was played with delicacy and a refined tone palette combined with an architectural shape ,never loosing the extraordinary finesse and subtle phrasing, but within a greater framework.There was an exemplary sense of harmonic structure as rarely heard sounds recreated an old ‘war horse’ as seen through the visionary eyes of a great artist. Even the rests were as pregnant with meaning as the actual sounding notes.The famous slow movement of the ‘Pathétique ‘ is only on a par with the ‘Moonlight’ for fame .Neither titles were given by the composer but designed by the publisher to sell and make popular the rather serious sounding word,’Sonatas’. Well they certainly succeeded as they were the two sonatas to be seen on the music stands of the obligatory piano that stood in most living rooms only to be ousted by the advent of the TV. There was a beautifully flowing seemless outpouring of Belcanto whispered beauty where even the gently hinted deep bass notes took on a new meaning. The Rondo,too,was played with delicacy but also a ‘ joie de vivre’ and rhythmic drive where the interruption with explosions of dynamic sounds took on a new significance.

Even the Sonata op 2 n.2 took on a new life with its tongue in cheek opening played with such insolent eloquence.The music spoke with charm and youthful exhilaration but also the sense of fantasy that was to reveal the true revolutionary genius of Beethoven.The ‘Appassionata’ I have never heard played with such extraordinary whispered lyricism where even the tumultuous explosions became mere blocks of moving harmonies. Whispered it might have been but I have never experienced ,since Pollini , such an overwhelming feeling of a masterpiece being unfolded with burning intensity.I remember Pollini ending his recital in Carnegie Hall with this sonata and being overwhelmed as today by a work that I thought I knew inside out.The true revelation came of course with the works of Schonberg .From the early almost Mendelssohnian /Brahmsian 1894 pieces to the sparse pieces of op 19 where there was a range of sounds of quicksilver fleetness allied to a rhythmic precision that brought these pieces vividly to life .Visions Fugitives Prokofiev called his early miniatures but these were Visions de vie of a world that cannot be described in words but can only be lived and experienced in sound as we did today.

What greater epitaph could there be to the Genius that was undoubtedly Pollini.

London salutes a legend. Maurizio Pollini – The story of a miracle by Antonio Morabito. ’One of the most remarkable descriptions of the humanity and courageous playing of a great artist I have ever read …. required reading for any musician and listener who values untouchable integrity in music and life itself …. an astonishing and creatively constructive piece of assessment …’ Michael Moran (distinguished Australian critic and musicologist in Warsaw)

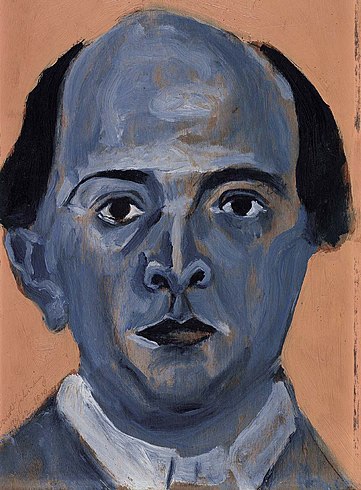

Emanuel Ax June 8, 1949 (age 74) Lviv Ukraine

Ax was born to a Polish-Jewish family to Joachim and Hellen Ax in Lviv, Ukraine , formerly part of the Soviet Union . Both parents were Nazi concentration camp survivors. Ax began to study piano at the age of six; his father was his first piano teacher. When he was seven, the family moved to Warsaw, where he studied piano the at Miodowa school. Two years later, Ax’s family moved to Winnipeg, Canada, where he continued to study music, including as a member of The Junior Musical Club of Winnipeg. In 1961, when Ax was 12 years old, the family moved to New York City, and Ax continued his piano studies under Mieczyslaw Munoz of the Juilliard School until 1976, when Munz left New York to teach in Japan. In 1970, Ax received his B.A. in French at Columbia University and became an American citizen. The same year, he won honorable mention at the VIII International Chopin Competition in Warsaw. In 1971, he won third place at the Vianna da Motta Competition.In 1972, he placed 7th at the Queen Elisabeth Competition in Brussels. He caught the public eye when he won the Arthur Rubinstein Competition in 1974, where he was personally congratulated by Rubinstein , who was a judge for the competition. The New York Times reported on Ax’s win in 1974 and said that in addition to a prize of $5,000, Ax “will receive the Artur Rubenstein Gold Medal engagements with the Israel Philharmonic and the BBC Orchestra ,a recording contract with RCA and an artist‐management contract with Hurok Artists.”Recalling his competition years, Ax said “You tend to forget how really awful the tension was. Here you were, No. 19, trying to play something better than No. 18. Ridiculous.” For Ax, saying which pianist is better is only a subjective judgement at the highest levels, “can anyone really go to piano recital and say Horowitz is better than Rubinstein? The most I can say is that Rubinstein speaks to me with greater voice than this one or that one.” Though he admits that competitions are a necessary means toward success for pianists, Ax hopes to never “sit on a jury and eliminate people”.

When speaking about performance reportoire, Ax said that one should not perform at a concert with pieces they have only learned recently: “People think pianists are lazy because they play the same works again and again, but it’s not that. It’s being afraid of something you haven’t done in public before. A conductor can do what he does very well whether his hands are cold or his baton is trembling. He can still get what he wants. But if I’m afraid, things will suffer. Physical and mental coordination must be perfect.”

Drei Klavierstücke (“Three Piano Pieces”), op .11, was written in 1909. And represent an early example of atonality in the Schoenberg’s work.

The tempo markings of the three pieces are:

- Mässige (at a moderate speed)

- Mässige (very slowly)

- Bewegte (with motion)

The first two pieces, dating from February 1909, are often cited as marking the point at which Schoenberg abandoned the last vestiges of traditional tonality.

The three pieces are given a unity of atonal musical space through the projection of material from the first piece into the other two, including recurring use of motivic material. The first of the three motivic cells of the first piece is used throughout the second, and the first and third cells are found in the third.

The third piece is the most innovative of the three. In its atomisation of the material and its agglomeration of the motivic cells through multiple connections, it isolates its musical parameters (mode of attack, rhythm, texture, register, and agogics) and employs them in a structural though unsystematic manner that foreshadows the integral serialism of the 1950s.

Sechs kleine Klavierstücke, Op. 19 (Six Little Piano Pieces) was published in 1913

After having written large, dense works such as Pelleas und Melisande, up until 1907, Schönberg decided to turn away from this style, beginning with his second string quartet of 1908. The following excerpt, translated from a letter written to Ferruccio Busoni in 1909, well expresses his reaction against the excess of the Romantic period:

‘My goal: complete liberation from form and symbols, cohesion and logic. Away with motivic work! Away with harmony as the cement of my architecture! Harmony is expression and nothing more. Away with pathos! Away with 24 pound protracted scores! My music must be short. Lean! In two notes, not built, but “expressed”. And the result is, I hope, without stylized and sterilized drawn-out sentiment. That is not how man feels; it is impossible to feel only one emotion. Man has many feelings, thousands at a time, and these feelings add up no more than apples and pears add up. Each goes its own way. This multicoloured, polymorphic, illogical nature of our feelings, and their associations, a rush of blood, reactions in our senses, in our nerves; I must have this in my music. It should be an expression of feeling, as if really were the feeling, full of unconscious connections, not some perception of “conscious logic”. Now I have said it, and they may burn me.’

This work was composed at the same time that Schoenberg was working on his orchestration of his massive Gurre- Lieder .While he maintained a lifelong love of Romantic music, the extreme contrast between his Klavierstücke and his more romantic works comes from his modernist desire to find a new means of expression. For him, works like the Gurre-Lieder or Verklarte Nacho fulfilled the tradition he loved, but it was works like these Klavierstücke that attempted to reach beyond it.The first five pieces were written in a single day, February 19, 1911, and were originally intended to comprise the entire piece. Schoenberg penned the sixth piece on June 17, shortly after the death of Mahler .Indeed, it is a, “well circulated claim that Schoenberg conceived op. 19/vi as a to beau to Mahler”.It was first performed on February 4, 1912, in Berlin, by Louis Closson.

The six pieces do not carry individual names, but are often known by their tempo marking:

- Leicht, zart (Light, delicate)

- Langsam (Slow)

- Sehr langsame (Very slow )

- Rasch, aber leicht (Brisk, but light)

- Etwas rasch (Somewhat brisk)

- Sehr langsam (Very slow)

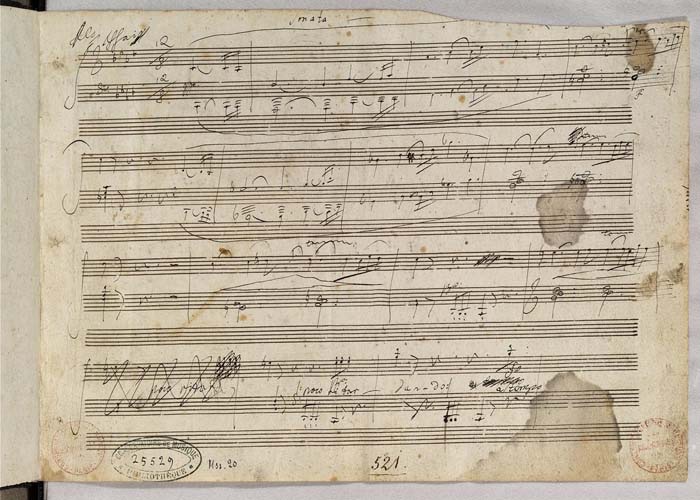

The Three Piano Pieces and Scherzo of 1894

A symphony theme cited by Schoenberg as having been written by him in about 1892 already shows a familiarity with Brahms’s Tragic Overture specifically, and with Brahms’s procedures of thematic evolution more generally (Frisch 1984, 159). Schoenberg’s Three Piano Pieces of 1894 are the first substantial instrumental compositions that survive, show that the twenty-year-old composer had continued to study Brahms intensively—in this case, the short piano works published recently in Brahms’s collections opp. 116, 117, 118, and 119 (1892–93).

3 pieces:

- Andantino

- Andantino grazioso

- Presto

Year/Date of Composition 1894. Publication 1968 Duration7 minutes

Ludwig van Beethoven baptised 17 December 1770 – 26 March 1827

Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 8 in C minor, Op. 13, commonly known as Sonata Pathétique, was written in 1798 when the composer was 27 years old, and was published in 1799 and is dedicated to his friend Prince Karl von Lichnowsky.

Although commonly thought to be one of the few works to be named by the composer himself, it was actually named Grande sonate pathétique (to Beethoven’s liking) by the publisher, who was impressed by the sonata’s tragic sonorities.

- Grave – Allegro di molto e con brio

- Adagio cantabile

- Rondo : Allegro

When the pianist and composer Ignaz Moscheles discovered the work in 1804, he was ten years old; unable to afford to buy the music, he copied it out from a library copy. His music teacher, on being told about his discovery, “warned me against playing or studying eccentric productions before I had developed a style based on more respectable models. Without paying heed to his instructions, however, I laid Beethoven’s works on the piano, in the order of their appearance, and found in them such consolation and pleasure as no other composer ever vouchsafed me.”

Anton Schindler ,a musician who was a friend of Beethoven in the composer’s later years, wrote: “What the Sonate Pathétique was in the hands of Beethoven (although he left something to be desired as regards clean playing) was something that one had to have heard, and heard again, in order to be quite certain that it was the same already well-known work. Above all, every single thing became, in his hands, a new creation, wherein his always legato playing, one of the particular characteristics of his execution, formed an important part.”

Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 2 in A major op 2 No. 2, was written in 1795 and dedicated to Joseph . It was published simultaneously with his first and third sonatas in 1796.

- Allegro vivace,

- Largo appassionato,

- Scherzo : Allegretto,

- Rondo : Grazioso,

Beethoven’s Sonata No. 23 in F minor, op 57 known as the Appassionata was composed during 1804 and 1805, and perhaps 1806, and was dedicated to Count Franz von Brunswick. The first edition was published in February 1807 in Vienna.

Unlike the early Pathetique the Appassionata was not named during the composer’s lifetime, but was so labelled in 1838 by the publisher of a four-hand arrangement of the work. Instead, Beethoven’s autograph manuscript of the sonata has “La Passionata” written on the cover, in Beethoven’s hand.

- Allegro assai

- Andante con moto

- Allegro ma non troppo – Presto