Aleksandr Skryabin (1872-1915)

Piano Sonata No. 2 in G sharp minor Op. 19 ‘Sonata Fantasy’

(1892-7)

I. Andante • II. Presto

Robert Schumann (1810-1856)

Kreisleriana Op. 16 (1838)

Äusserst bewegt • Sehr innig und nicht zu rasch •

Sehr aufgeregt • Sehr langsam • Sehr lebhaft •

Sehr langsam • Sehr rasch • Schnell und spielend

Fryderyk Chopin (1810-1849)

Scherzo No. 1 in B minor Op. 20 (c.1833)

Scherzo No. 2 in B flat minor Op. 31 (1837)

Scherzo No. 3 in C sharp minor Op. 39 (1839)

Scherzo No. 4 in E Op. 54 (1842-3)

Boris Giltburg at the Wigmore Hall with a first half of all fantasies :Scriabin Second (Fantasy) Sonata and Schumann’s Kreisleriana.Some beautifully sensitive playing of the first movement of Scriabin with ravishing colours and a sense of balance that allowed the melodic line always to be revealed wrapped as it was in sumptuous golden streams of sound.The second movement was played with dynamic drive and throbbing passion with a kaleidoscope of sounds that allowed for a dynamic range of searing passion mixed with subtle delicacy . Playing with an I pad heroically in view he gave an exemplary performance of one of Scriabin’s most loved Sonatas.

I had heard recently a recording from the Wigmore Hall of Boris Giltburg giving a magnificent performance of Chopin’s 24 Preludes.Although he had the I pad as an aide memoire he never seemed to need it as the 24 problems,as Fou Ts’ong used to call them ,were 24 jewels in a sumptuous crown of nobility,elegance and grandeur.

So it was with great expectancy that I awaited a similar performance of Chopin’s Four Scherzi preceded by Schumann’s eight fantasies that make up Kreisleriana.

Not helped by a rather metallic sounding Fazioli piano Kreisleriana sounded rushed and rather erratic with exaggerated contrasts not only of sound but also tempo.There were of course many beautiful moments such as the central episode of the first fantasy or the beautiful simplicity of the first part of the fourth ( where surely ‘bewegter ’ means moving not actually slower?)The third sound strangely disjointed and although the central episode was played with great beauty it seemed strangely divorced from its surroundings.The fifth whilst being rhythmically very clear seemed to lack any real substance to the sound in the more lyrical passages that follow.The sixth was so whispered as to be almost inexistant before the rather unhinged attack of the seventh that like the first had seemed strangely out of control.The central episode was played by the left hand alone and revealed an absolute technical mastery that made its surroundings even more incomprehensible.Surely the final chords are part of what precedes them and is just a way of slowing down the tension?The eighth was the most successful where the absolute clarity of the right hand was beautifully judged contrasting with the long bass held notes.The first contrasting episode though was strangely sotto voce whereas the second was anything but sotto voce and made one wonder whether Floristan had suddenly woken from a deep sleep with a start.

Unfortunately the Chopin Scherzi fared no better with hurried frantic passage work in the first that although played with great drive and accuracy seemed strangely out of control.The beautiful Polish carol of the central episode was almost inaudible as more attention was shown to the top notes of the accompaniment than to the beautiful melody in the tenor or alto register.The second was played with great rhythmic energy and contrast but the central episode so divorced from its surrounding as to make any architectural sense of this well known masterpiece impossible.A very exciting ending and as at the end of the first had Giltburg happy to interrupt the continuity of this quartet of Scherzi with applause.The opening of the third I have never heard played so well but then the octaves that followed were like guns going off and totally divorced from the magnificent introduction that had preceded them.The chorale was played so sotto voce that even for Giltburg made it difficult to control the cascades of notes that illuminate this glorious almost religious outpouring.The fourth scherzo in a way suited Giltburg with its fleeting silf like changes of character but again the glorious cantabile of the central episode was barely whispered and the octaves at the end were more worthy of Tchaikowsky than poor old Chopin!

An almost inaudible and mannered performance of Clare de lune was cheered to the rafters by the ever generous Wigmore Hall audience and I was just sorry to have eavesdropped on an occasion that was so very different from the one I had been expecting.Chopin plus it was billed as from an illustrious artist in residence which was obviously not the case tonight.

Boris Giltburg an avalanche of Diabolic suggestions take the Wigmore by storm

Kreisleriana, op 16, is a in eight movements and subtitled Phantasien für das Pianoforte. Schumann claimed to have written it in only four days in April 1838[and a revised version appeared in 1850.It is dedicated to Chopin , but when a copy was sent to the Polish composer, “he commented favorably only on the design of the title page”.

- Äußerst bewegt (Extremely animated),

- Sehr innig und nicht zu rasch (Very inwardly and not too quickly). This movement in ABACA form, with its lyrical main , includes two contrasting intermezzi.In his 1850 edition, Schumann extended the first reprise of the theme by twenty measures in order to repeat it in full.

- Sehr aufgeregt (Very agitated),

- Sehr langsam (Very slowly), B♭ major/G minor

- Sehr lebhaft (Very lively), G minor

- Sehr langsam (Very slowly), B♭ major

- Sehr rasch (Very fast),

- Schnell und spielend (Fast and playful), G minor. Schumann used material from this movement in the fourth movement of his first symphony

Kreisleriana is a very dramatic work and is viewed by some critics as one of Schumann’s finest compositions.In 1839, soon after publishing it, Schumann called it in a letter “my favourite work,” remarking that “The title conveys nothing to any but Germans. Kreisler is one of E.T.A. Hoffmann’s creations, an eccentric, wild, and witty conductor.”

Like the kaleidoscopic Kreisler, each movement has multiple contrasting sections, resembling the imaginary musician’s manic depression , and recalling Schumann’s own “Florestan” and “Eusebius,” the two characters Schumann used to indicate his own contrasting impulsive and dreamy sides.

In a letter to his wife Clara , Schumann reveals that she has figured largely in the composition of Kreisleriana:

‘I’m overflowing with music and beautiful melodies now – imagine, since my last letter I’ve finished another whole notebook of new pieces. I intend to call it Kreisleriana. You and one of your ideas play the main role in it, and I want to dedicate it to you – yes, to you and nobody else – and then you will smile so sweetly when you discover yourself in it.’

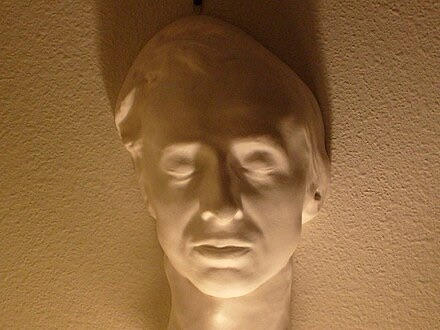

Fryderyk Franciszek Chopin

1 March 1810 Zelazowa Wola ,Poland

17 October 1849 (aged 39) Paris, France

Chopin’s four scherzos were composed between 1833 and 1843. They are often linked to his four ballades , composed in roughly the same period; these works are examples of large scale autonomous musical pieces, composed within the classical framework, but surpassing previous expressive and technical limitations. Unlike the classical model, the musical form adopted by Chopin is not characterised by humour or elements of surprise, but by highly charged “gestures of despair and demonic energy”.Schumann wrote of the first scherzo : “How is ‘gravity’ to clothe itself if ‘jest’ goes about in dark veils?”Starting in the early 1830s, after his departure from Poland, Chopin’s musical style changed significantly, entering a mature period with compositions of exceptional single-movement pieces on a monumental scale, stamped with his unmistakable signature. There were ten of these extended works—the four ballades, the four scherzos and the two fantaisies (op 49 and 61) This musical transformation was preceded by Chopin’s new attitude to life: after adulation in Warsaw, he felt disillusioned by lukewarm audiences in Vienna; then his prospects as a pianist-composer seemed less inviting; and lastly nostalgia and the recent 1830 Polish uprising drew him back spiritually to Poland. The musical form “scherzo” comes from the Italian word ‘joke’. In its classical form, it is usually part of a multi-movement work, in triple time with a lively tempo and light-hearted mood. Beethoven’s scherzos perfectly exemplify this type of movement, with characteristic sforzandi off the beat, clearly articulated rhythms and rising or falling patterns.Chopin’s four scherzos enter into a different and grander realm. They are all marked presto or presto con fuoco and “expand immeasurably both the scale of the genre and its expressive range”. In these piano pieces, particular the first three, any initial feeling of levity or jocularity is replaced by “an almost demonic power and energy”.

Each of the four scherzos starts with abrupt or fragmentary motifs, which create a sense of tension or unease. The opening gestures of Scherzo No. 1 involve texture, dynamics and range: strident chords are followed by rapid will-o-the-wisp passagework, rising with crescendos—motifs that recur during the movement. In Scherzo No. 2, the initial fragmentary sotto voce rumblings are followed by a dramatic forceful response, all of which are repeated. The gesture that begins Scherzo No. 3 is similar to that of Scherzo No. 2, but less pronounced. The beginning of Scherzo No. 4 alternates two contrasting textures and harmonies—first subdued chords and then faster arched figures that rise and fall with the dynamics. In summary, Chopin established the one-movement scherzos as a genre in which the piece grew out of the opening fragmentary gestures, heard at the outset in the initial short and contrasting musical ideas.

6 January 1872 Moscow 27 April 1915 Moscow

Scriabin’s Piano Sonata No. 2 in G-sharp minor, (op. 19, also titled Sonata-Fantasy) took five years for him to write. It was finally published in 1898, at the urging of his publisher. ‘You’ve had that piece long enough! Send it to me right away.’ Skryabin’s publisher and friend, Mitrofan Belyayev, was referring Sonata No. 2 in G sharp minor Op. 19, a work that,despite its modest length, was almost six years in the

making. ‘It has been revised seven times’, the

composer remarked, before finally submitting it to

Belyayev in 1898.

In 1894 he had agreed to pay Scriabin to compose for his publishing company (he published works by notable composers such as Rimsky-Korsakov- Korsakov and Glazunov). In August 1897, Scriabin married the pianist Vera Ivanovna Isakovich, and then toured in Russia and abroad, culminating in a successful 1898 concert in Paris. That year he became a teacher at the Moscow Conservatory and began to establish his reputation as a composer. During this period he composed his cycle of etudes , Op. 8, several sets of preludes , his first three piano sonatas, and his only piano concerto , among other works, mostly for piano.

For five years, Scriabin was based in Moscow, during which time his old teacher Safonov conducted the first two of Scriabin’s symphonies.

P.S.

Christopher, your review of the Giltburg recital was one of the most honest and accurate that I have ever read. Last evening, I began to worry that my hearing was defective, but your review this morning has encouraged me to believe that I am retaining my faculties. I was tempted to leave at the interval after the divine Schumann was so badly mangled.

David Carhart thank you dear friend he is only the second person that I have allowed my feelings to take over but I had heard his Chopin Preludes on the Wigmore Website and thought that after the awful mangled Schumann he would give us some insights …but alas this was not the case and the encore summed up his musicianship that is on a par with Babayan …..the only other person I have allowed myself to describe what horrors were being enacted on such a hallowed stage …….I was incensed of the ignorance of taste of a public who could give him an ovation after such a feast ….it gave me indigestion and I hurried home as fast as I could thanking God that I had heard Alim the other day with hard work and humility transmitting the composers wishes to us …I just hope he survives the sharks that are out to cash in on artists who are ready to sacrifice their artistic integrity pushed by the machinery that can offer them concerts ………..quantity rather than quality …..the pressure and temptation is great.But of course I remember Brendel playing K271 and with that saying farewell to the concert platform before his powers diminished ………….what is this I pad thing that is so readily accepted in solo concerts …….even concertos now and no one remarks on it ………….