Alim Beisembayev piano

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Piano Sonata No. 23 in F minor Op. 57 ‘Appassionata’ (1804-5)

I. Allegro assai • II. Andante con moto •

III. Allegro ma non troppo – Presto

Piano Sonata No. 31 in A flat Op. 110 (1821-2)

I. Moderato cantabile molto espressivo •

II. Allegro molto • III. Adagio ma non troppo – Fuga.

Allegro ma non troppo

Interval

Aleksandr Skryabin (1872-1915)

4 Preludes Op. 22 (1897)

Prelude in G sharp minor • Prelude in C sharp minor •

Prelude in B • Prelude in B minor

Sergey Rachmaninov (1873-1943) Prelude in B minor Op. 32 No. 10 (1910)

Etude-tableau in D Op. 39 No. 9 (1916-7)

Maurice Ravel (1875-1937)

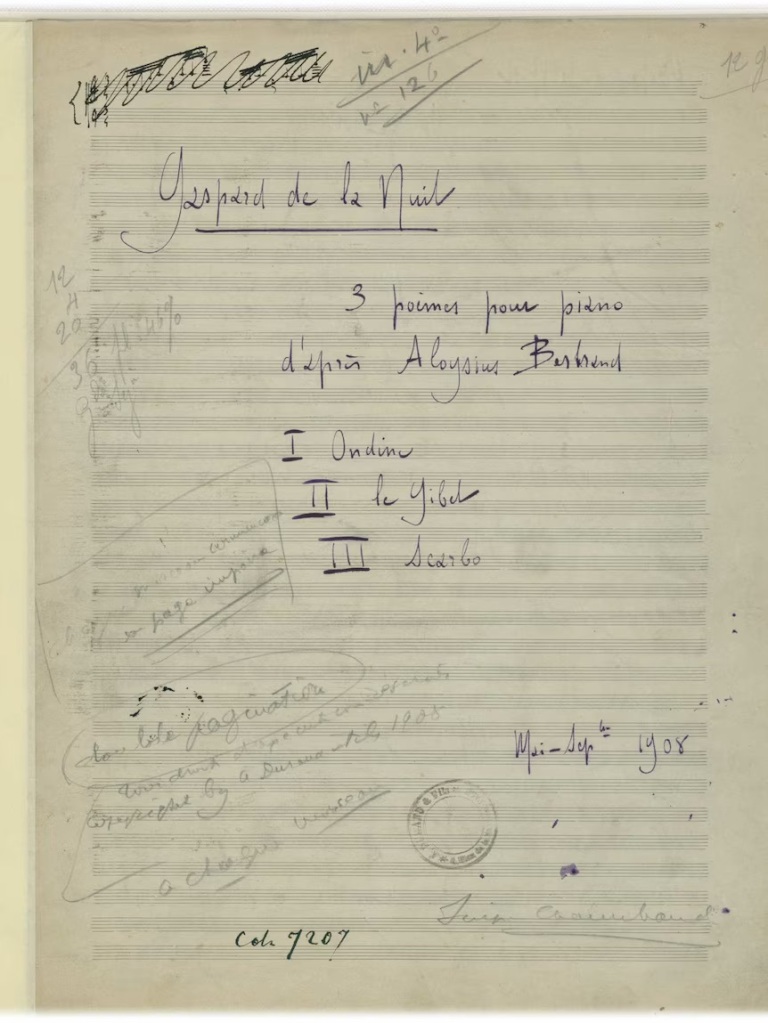

Gaspard de la nuit (1908)

I. Ondine • II. Le gibet • III. Scarbo

Alim Beisembayev in a major London recital at the Wigmore Hall .

A programme that already showed the credentials of great artistic integrity.

When these days do young musicians play two Beethoven Sonatas as an opener to an important London recital?

Only a fool or a great artist would dare open with the ‘Appassionata’ followed by Beethoven’s antidote to a turbulent life with the mellifluous, sublime outpouring of his penultimate sonata op 110.

Alim is certainly no fool and is quite simply one of the finest musicians I have heard since Serkin.A rhythmic precision and attention to the minutest details in the score of Boulezian clarity. Silences that were truly golden and were the anchors that we could hold on to inbetween the marvels that were being recreated before our very eyes .

An ‘Appassionata’ of startling contrasts that had us on the edge of our seats as if newly minted. The opening of op 110 after the extraordinarily relentless onslaught of the Presto ending of the ‘Appassionata’ was of such sublime beauty as Alim waited until he could feel we were all with him before gently caressing notes that like the fourth Concerto are of celestial genius.

There was magic in the air indeed and a great artist treating us with humility and mastery to performances the like of which has been missing too long from the concert hall .

We are getting too used to artists appearing before the public with the I pad in a desperate attempt to keep up with the speed with which concert artists are obliged to be entreated by people who are more interested in quantity than quality.

But it is the tension that is missing as was so evident today as this young man played with simplicity and humility what the composer had actually written .He had digested the score but more than that because it was the very meaning behind the notes that was both enthralling and enlightening . There were no nice conveniently turned corners to this young man’s Beethoven but the sinuous tempestuous impatience that we know was the man Beethoven.

A live performance should be like the man on the high wire holding us in his hands with electrifying suspence as was the wont of a Serkin or a Brendel.The surprise element ,the voyage of discovery that can unite strangers gathered to share in such experience is what we were treated to today.

As Gilels used to declare the difference between live music and recorded is that between fresh or canned food .I will never forget Serkin at the end of the ‘Hammerklavier’ in London holding onto the last chord as though his life depended on it,shaken as we all were after a tumultuous and even tortuous voyage of discovery together.Or Arrau at the end of the Beethoven Trilogy so overwhelmed as we all were he could never have had a quick cup of tea and repeated such a miracle to appease the crowds who demanded a return fight!

There were many things to appreciate again and so will just jot down some thoughts of a continual voyage of discovery.This too I have heard Serkin play in London and have never forgotten the passion and frenzy he brought to the final pages where the final A flat chord spread up and down the keyboard over five bars was an explosion of atomic energy the like of which I thought could never be matched and will certainly never be forgotten.As Mitsuko Uchida so rightly said when asked if her recital could be recorded or photographs taken:’A recital should remain and grow in one’s memory and not be a copy on the printed page that fades with time!’ Alim waited after the tumultuous Appassionata for just the right moment to caress the keys that took us to the sublime belcanto melody that opens this most beautiful of all Sonatas.Scales that just wafted up and down the keyboard ‘leggiermente’ that were merely clouds of shifting harmonies leading to the purity of the melodic line etched on high before leading in turn to the agitated left hand chords with the right hand moving in contrary motion so beautifully phrased without ever altering the tempo.There was magic in the air when with all simplicity E flat suddenly became D flat and we were involved in the miraculous meanderings of the left hand with the melodic line played so simply above it.The coda was played with disarming simplicity again scrupulously in time but with extraordinary clarity of phrasing.The contrast between ‘piano’ and ‘forte’ in the scherzo was quite overwhelming and the ease with which he plunged into the notoriously tricky trio made the syncopated rhythms even more poignant.Waiting for the exact moment to allow the Adagio to emerge from the whispered long held final chord of the scherzo.The control of sound whilst scrupulously observing Beethoven’s very precise pedal markings was quite remarkable as he was able to phrase with such sensibility every minute detail.The pulsating chords were indeed Beethoven’s heart beating where the keys were never allowed to be struck but here was the real ‘bebung’ ( mere vibrations of sound) brought to life on a very different instrument than Beethoven’s.The inner counterpoints of yearning I have never heard played with such poignant delicacy or meaning.The four notes C,B flat,E flat and A flat were followed by a rest that I had never realised was so emotionally important until listening to Alim today.Of course they were to be repeated on the return of the Aria with devastating effect.The fortissimo entry of the fugue subject amid such chattering knotty twine was quite breathtaking as was the sudden change from E flat to D just before the return of the Aria.Timed so perfectly we have heard it hundreds of times but never like this ….it was truly a moment that will remain in my memory as a moment to cherish.The gradual build up to the tumultuous triumphant exhultation was masterly for Alim’s aristocratic control that allowed him to unleash the final A flat chord on us unsuspecting mortals who were left breathless and truly uplifted.Who could ever forget Serkin shaking at the end with hands thrown high as if being struck by lightening.

What a lesson we were treated to tonight by this young man who was trained in British Institutions that have nurtured his great natural talent and imbued him with a technical mastery that allows him to delve deep into the very heart of the creative genius of the composers he is serving .Je sens,je joue je trasmets has never found a greater advocate……..

What a superb start to the second half of the concert with a very short survey of Russian music with ravishing beauty of nobility,sensuality and nostalgia.Four preludes op 22 by Scriabin that with Alim’s chameleonic sense of colour and mood was a multicoloured feast of fluidity and luminosity.The sumptuous hidden passion of the first was followed by a mere page of sublime simplicity and the capricious play with sounds of the third.They lead so naturally to the Romantic effusions of the last in B minor and behold a miracle that this was transformed as if by magic into the ‘Return’ by Rachmaninov in the same key.The Prelude in B minor with its improvised searching character was a favourite of the composer and his great friend Moiseiwitch who had delved deep into this miniature tone poem and found the same poetic meaning as the composer intended.The gentle opening lead to an overpowering climax that was so gradual and well balanced that we were not aware of how overwhelming it would be .Immediately there was a desolate nostalgic calm like a light being turned off . Such was Alim’s mastery of sound he could lead us where he wanted to as he had a story to tell with his sensitive fingers and kaleidoscopic sense of colour.Of course the final word was from Rachmaninov with the extraordinary sumptuous outpouring of the Etude – tableau op 39 n. 9 .Even here though there was a story to tell as the dynamic opening energy subsided and there was the contrasting episode of crystal like clarity where all the strands of counterpoint could be heard chattering amongst themselves as the excitement grew to fever pitch and the final gloriously sumptuous outpouring of grandeur and nobility allied to an almost animal pitch of excitement.

Gaspard de la nuit was the closing work of the recital and it held no terror for Alim .His only concern was to transmit Ravel’s extraordinary recreation of the poems by Bertrand even though Ravel had set out to test the technical prowess of pianists by writing a piece of equal if not more difficulty that Balakirev ‘s notorious Islamey.Technical considerations just disappeared as we were taken into a magic world of sounds with the delicacy and fluidity of Ondine.There were ‘puffs’ of colour that appeared as if by alchemy when least expected.An extraordinary sense of line that no matter how complex the texture Ondine shone through as she darted from one end of the keyboard to the other with silf like precision.After the tumultuous climax Ondine was left on her own barely a whisper bathed in pedal .In Alim’s hands ,like his long pedals that Beethoven demands,suddenly made sense and added some quite extraordinary colours to an instrument that is after all a box of hammers and strings.How can one possibly persuade us that it can sing as beautifully as the human voice ?By artistry,technical mastery but above all a supreme sense of balance .Alim is not only a courageous high flyer but a supreme illusionist as were the pianists in the so called Golden Age of piano playing .Was it not Matthay who said that in each note on the piano there are a hundred different gradations of sound depending on how the keys are touched.

Seeing Stephen Kovacevich in the audience applauding his younger colleague I am reminded of his great mentor Myra Hess – the star student of Uncle Tobbs at the Royal Academy.The desolate sounds of Le Gibet were of such insistence and the bass notes gave the needed anchor on which the gallows could swing with such frightening isolation.Scarbo entered in this desolate atmosphere with a remarkable clarity.The deep bass notes I have never heard so clearly defined as the vibrating chords – like in Beethoven’s aria of op 110 – unbelievably were like blowing on the keys such was their extraordinary unpercussivness.I remember Agosti pushing my fingers nearer the keys never to hit but caress and pull sounds that are hidden deep within the black and white keys of this great black beast.Perlemuter too changing fingers many times on one note like an organist to feel the weight within the keys as you slid from one to the other never letting go.

Here again it was the silences that were so overwhelming in their impact not only of the silence but what came immediately afterwards.In the central episode I have never been aware of the fact that this is Ondine again raising her head before being dragged into the infernal furness of the triumphant Scarbo.Extraordinary technical mastery and passionate involvement from Alim who like the great masters of the past would show and guide us to the one and only climax in a piece and it was this that gave such architectural authority to his performances.Rubinstein of course was the prime example who even in his late 80’s would suddenly inject a work with electric energy sometimes even rising from the seat to do so.

The tricks of the trade my old teacher Sidney Harrison used to call them.But what trade ?That of master musicians who are totally dedicated to their art.That is what I was reminded of today as Alim was cheered to the rafters by the discerning Wigmore Hall public and persuaded to play two encores that were indeed the cherry on a sumptuous cake.

Chopin Prelude op 28 n.17 .The deep A flat in the bass created a sound where the melodic line could appear as an apparition from afar a ‘Cathédrale engloutie’ indeed .And finally a ‘Chasse Neige’ by Liszt that made one realise what a true genius Liszt was when his works are played with the intelligence and fantasy that we heard today.Every bit as frightening as Scarbo as the whispered chromatic scales built to a terrifying climax – never hard or ungrateful but the sumptuous and ravishingly beauty of a truly ‘Grand’ piano.

Alim Beisembayev – The poetic vision of a great artist

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2021/05/19/bocheng-wangs-wondrous-chopin-at-st-marys/

Gaspard de la nuit (subtitled Trois poèmes pour piano d’après Aloysius Bertrand), M.55 was written in 1908. It has three movements , each based on a poem or fantaisie from the collection Gaspard de la Nuit – Fantasies à la manière de Rembrandt e de Callot completed in 1836 by Aloysius Bertrand . The work was premiered in Paris, on January 9, 1909, by Ricardo Vines.

The piece is famous for its difficulty, partly because Ravel intended the Scarbo movement to be more difficult than Balakirev’s Islamey . Because of its technical challenges and profound musical structure, Scarbo is considered one of the most difficult solo piano pieces in the standard repertoire.

When Ravel was shown the work, some 50 years later, something in Bertrand’s vivid depictions, full of fantastical creatures, spectral netherworlds and gothic darkness, connected with the composer’s own fascination with mysteries of the unknown.

But there was something else about the rhythm and syntax of Bertrand’s writing that Ravel found intriguing, and which seemed to provide a perfect vehicle for the ideas that had been swirling in his imagination and had been briefly glimpsed in other works of the period.

The name “Gaspard ” is derived from its original Persian form, denoting “the man in charge of the royal treasures”: “Gaspard of the Night” or the treasurer of the night thus creates allusions to someone in charge of all that is jewel-like, dark, mysterious, perhaps even morose.

Of the work, Ravel himself said: “Gaspard has been a devil in coming, but that is only logical since it was he who is the author of the poems. My ambition is to say with notes what a poet expresses with words.”

Aloysius Bertrand , author of Gaspard de la Nuit (1842), introduces his collection by attributing them to a mysterious old man met in a park in Dijon , who lent him the book. When he goes in search of M. Gaspard to return the volume, he asks, “ ’Tell me where M. Gaspard de la Nuit may be found.’ ‘He is in hell, provided that he isn’t somewhere else’, comes the reply. ‘Ah! I am beginning to understand! What! Gaspard de la Nuit must be…?’ the poet continues. ‘Ah! Yes… the devil!’ his informant responds. ‘Thank you, mon brave!… If Gaspard de la Nuit is in hell, may he roast there. I shall publish his book.’ ”

Beethoven’s A flat major Sonata, Op 110, was his penultimate sonata, written in 1821,

The outward gentleness of the opening movement belies its tautness of form, and the contrast with the brief second, a scherzo marked Allegro molto – capricious, gruffly humorous, even violent – is extreme. Beethoven subversively sneaks in references to two street songs popular at the time: Unsa Kätz häd Katzln ghabt (‘Our cat has had kittens’) and Ich bin lüderlich, du bist lüderlich (‘I’m dissolute, you’re dissolute’)!

Facsimile of last movement p.43

But it’s in the finale that the weight of the sonata lies, and it begins with a declamatory, recitative-like passage that starts in the minor, moving to an emotionally pained aria-like section.Beethoven introduces a quietly authoritative fugue, based on a theme reminiscent of the one that opened the sonata. Its progress interrupted by the aria once more, its line now disjunct and almost sobbing for breath. The way in which the composer moves into the major via a sequence of G major chords is a passage of pure radiance, that Edwin Fischer described as ‘like a reawakening heartbeat’. This leads to a second appearance of the fugue in inversion culminating in a magnificently triumphant conclusion.

This is a recently made master of op 111 https://drive.google.com/file/d/1zdb2qjgWnA3HyPph_6FxnxjLHy7APc_f/view?usp=drive_web

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2024/01/03/forli-pays-homage-to-guido-agosti/

In the summer of 1819, Adolf Martin Schlesinger from the Schlesinger firm of music publishers based in Berlin sent his son Maurice to meet Beethoven to form business relations with the composer.The two met in Modling,where Maurice left a favourable impression on the composer.After some negotiation by letter, the elder Schlesinger offered to purchase three piano sonatas for 90 ducats in April 1820, though Beethoven had originally asked for 120 ducats. In May 1820, Beethoven agreed, and he undertook to deliver the sonatas within three months. These three sonatas are the ones now known as Op. 109,110, and 111 the last of Beethoven’s piano

Beethoven’s own markings with the ‘bebung‘ or vibrated notes in the Adagio of op.110

The composer was prevented from completing the promised sonatas on schedule by several factors, including his work on the Missa solemnis (Op. 123),rheumatic attacks in the winter of 1820, and a bout of jaundice in the summer of 1821.Op. 110 “did not begin to take shape” until the latter half of 1821.Although Op. 109 was published by Schlesinger in November 1821, correspondence shows that Op. 110 was still not ready by the middle of December 1821. The sonata’s completed autograph score bears the date 25 December 1821, but Beethoven continued to revise the last movement and did not finish until early 1822.The copyist’s score was presumably delivered to Schlesinger around this time, since Beethoven received a payment of 30 ducats for the sonata in January 1822.

Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 23 in F minor, op 57 , known as the Appassionata, was composed during 1804 and 1805, and perhaps 1806, and was dedicated to Count Franz von Brunswick. The first edition was published in February 1807 in Vienna

The ‘Appassionata’ was not named during the composer’s lifetime, but was so labelled in 1838 by the publisher of a four-hand arrangement of the work. Instead, Beethoven’s autograph manuscript of the sonata has “La Passionata” written on the cover, in Beethoven’s hand.

Alim Beisembayev won First Prize at The Leeds International Piano Competition in September 2021, performing Rachmaninov’s Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra and Andrew Manze. He also took home the medici.tv Audience Prize and the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Society Prize for contemporary performance, with The Guardian praising him as a “worthy winner” with a “real musical personality”.Announced as a BBC New Generation Artist 2023-25, in summer 2023 Alim made his Royal Albert Hall BBC Proms debut performing Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto No. 2 with the Sinfonia of London conducted by John Wilson broadcast live on BBC Radio 3 and recorded for BBC Television.Further highlights in the 2023/24 season include debuts with the BBC Symphony (Jonathan Bloxham), BBC Philharmonic (Joshua Weilerstein), Bournemouth Symphony (Tom Fetherstonhaugh) and Enescu Philharmonic as well as returning to the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic (Domingo Hindoyan) to perform the World Premiere of a new piano concerto by Eleanor Alberga.Recent concerto highlights include with the Barcelona Symphony Orchestra (Pablo Rus Broseta), Royal Liverpool Philharmonic (Case Scaglione), BBC Symphony Orchestra (Clemens Schuldt), Oxford Philharmonic, SWR Symphonieorchester Stuttgart (Yi-Chen Lin), RCM Symphony Orchestra (Sir Antonio Pappano), National Symphony Orchestra of India, State Academic Symphony Orchestra of Russia “Evgeny Svetlanov” and Fort-Worth Symphony.As a recitalist, Alim has made notable debuts at the BBC Proms at Truro, the Chopin Institute in Warsaw, Oxford Piano Festival, Wigmore Hall, Fondation Louis Vuitton (Paris) and Cliburn Concerts in addition to a tour of Europe in association with the Steinway Prizewinner Concerts Network, and Korea, with the World Culture Network. Upcoming recitals include his debut at the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam, Birmingham Town Hall and return visits to the Seoul Arts Centre and Wigmore Hall among others.In December 2022, Warner Classics released Alim’s debut album: Liszt Transcendental Études, featuring all twelve of the composer’s etudes which was met with critical acclaim.Born in Kazakhstan in 1998, Alim’s early studies were at the Purcell School where he won several awards, including First Prize at the Junior Cliburn International Competition. Alim was taught by Tessa Nicholson at school and continued his studies with her at the Royal Academy of Music. In 2023, Alim completed his Masters’ and Artist Diploma in Performance at the Royal College of Music where he studied with Professor Vanessa Latarche. He is generously supported by numerous scholarships such as the Imogen Cooper Music Trust, ABRSM, the Countess of Munster, Hattori Foundation, the Drake Calleja Fund trusts, and belongs to the Talent Unlimited charity scheme.

2 risposte a "Alim Beisembayev at the Wigmore Hall bewitched and enriched by the man on the high wire"