Tamsin Waley-Cohen violin George Xiaoyuan Fu piano

A duo recital in the true sense of the word with a musical conversation between equals.

A Mozart Sonata of refined elegance and operatic energy.The opening Largo was played with coquettish simplicity before bursting into an Allegro of scintillating playful energy. There was great delicacy from the piano in the Andante as the violin played with ever more intensity.The elegance and mellifluous sounds were mirrored in a performance where they played as one.It was a tribute to the pianist’s musicianship and technical prowess that with the piano lid fully open there was never a moment when the sound of this great black beast could have overpowered the beauty,musical line and sweetness of tone of Tamsin’s Stradivarius.

The revelation of the evening though was the UK premiere of ‘Swan Song’ by Serkin’s grandson David Ludwig.The charm and persuasion of George Fu are such as to persuade Tamsin to include a long contemporary work in an important London concert.David Ludwig had been George’s composition teacher at Curtis and obviously it was he who had persuaded her of the importance of the work.A work of startling technical and musical complexity with cruel demands on both players who managed to play with a clarity and sense of architectural shape that revealed a work of great effect and beauty.The magic luminosity from the piano at the opening allowed the violin to soar above such gossamer sounds with long drawn out musical lines.There were dramatic contrasts with the piano creating clouds of sound even with a little help from inside its own body.An elaborate cadenza for solo violin lead to the appearance from afar of the Schubert Fantasy that had been the composers inspiration.Tamsin rose magnificently to the gauntlet that George had lain before her and with superb control and revelatory imagination placed an important work in the midst of the other two recognised masterpieces in her recital.

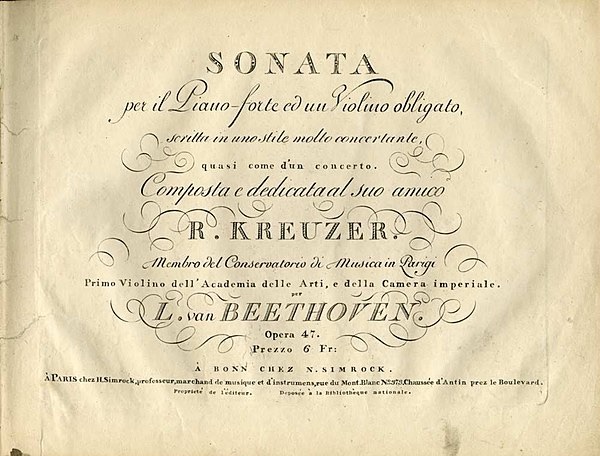

Beethoven’s ‘Bridgetower’ Sonata …better known by it’s final dedicatee’s name ‘Kreutzer’ filled the second half of the concert with magnificence of grandeur and dynamic rhythmic energy .There were moments of sublime beauty but these were but the calm before the storm.An aristocratic control over this cauldron of boiling energy as they played with perfect ensemble each artist listening to the other creating an architectural whole united as they both were for the glory of the music that had been entrusted to them.There was a simple beauty to the Andante and variations that was allowed to flow so naturally giving them the freedom to shape and mould each variation with a flexibility of pulse and beguiling sense of style.The delicacy of the first variation with the violin just commenting of the marvels that were being revealed from the piano.Followed by the delicately shaped ‘leggermente’ filigree jeux perlé from the violin.The almost too pompous minor variation was contrasted with the luminous fluidity of the major IV variation.There was finally a glimpse of the sublime beauty that had been hinted at as they were united in the magical final bars that gradually finished with whispered intent at the extremes of both instruments.Suddenly the call to arms and the chase was on as the Finale ,Presto burst upon the scene with dynamic driving energy.This was a performance of technical and musical mastery from both players and gave a monumental finish to an evening of remarkable music making of humility ,intelligence and mastery.

‘Après une rève ‘ was offered as an encore and as Tamsin said :’a much needed balm after such dynamism‘.It was played with ravishing sounds of quiet intensity where Mr Stradivarius was allowed the wings to soar into places where only music can reach.George at the piano with fearless backing that gave great depth and spiritual meaning to the wings with which Tamsin had now been bestowed.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791)

Violin Sonata in B flat K454 (1784)

I. Largo – Allegro

I I. Andante

III. Allegretto

David Ludwig (b.1974)

Swan Song (2013) UK première

Interval

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Violin Sonata No. 9 in A Op. 47 ‘Kreutzer’ (1802-3)

I. Adagio sostenuto – Presto

I I. Andante con variazioni

III. Finale. Presto

Violin Sonata No. 32 in B flat K .454 was composed in Vienna on April 21, 1784. It was published by Christoph Torricella in a group of three sonatas (together with the piano sonatas K.284 and K.333 )

The sonata was written for a violin virtuoso Regina Strinasacchi of Mantua to be performed by them together at a concert in the Karntnerthor Theatre in Vienna on April 29, 1784.

‘We now have here the famous Strinasacchi from

Mantua,’ Mozart wrote to his father on 24 April 1784,

‘a very good violinist. She has a great deal of taste and

feeling in her playing. I am this moment composing a

sonata which we are going to play together on

Thursday at her concert in the theatre.’

Although Mozart had the piano part securely in his head, he did not give himself enough time to write it out, and thus it was performed with a sheet of blank music paper in front of him in order to fool the audience. According to a story told by his widow Constanze Mozart , the Emperor Joseph II saw the empty sheet music through his opera glasses and sent for the composer with his manuscript, at which time Mozart had to confess the truth, although that is likely to have amazed the monarch rather than cause his irritation.

Of this piece, dating

from 2013, he has written as follows:

‘Swan Song is one of three pieces of mine that draw

directly from the materials of a past musical work, in

this case Schubert’s Fantasy for Violin and Piano in C

major, D. 934. I felt like I was writing a play with many

characters who are having separate conversations

about the same piece of music.

‘The work models Schubert in weaving in and out of

a chain of related passages that linked together form

a fantasy, playing for a little over 15 minutes. The

opening passage appears several times throughout

the piece, each time a little different (but always

sparkling!), as if transformed by all of the music

preceding it. In between are fast passages with quick

exchanges between violinist and pianist, music in the

extremes of volume and register, and many little

games and conversations with Schubert.

‘There are many characters, with their exits and

their entrances, each making a statement and then

stepping back for the next to take centre stage. At

one point, Schubert himself makes a brief

appearance, but he is a phantom who emerges into

the light and returns to the background as quickly as

he appeared. Finally, after increasingly fast music that

seems to plough headlong into a brusque ending,

hope appears, rising toward a resolution of the quiet

questions asked in the first twinkling sonorities of the

piece.’

The sonata was originally dedicated to the violinist George Bridgetower m (1778–1860) as “Sonata mulattica composta per il mulatto Brischdauer [Bridgetower], gran pazzo e compositore mulattico” (Mulatto Sonata composed for the mulatto Brischdauer, great madman mulatto composer). Shortly after completion the work was premiered by Bridgetower and Beethoven on 24 May 1803 at the Augarten Theatre at a concert that started at the unusually early hour of 8:00 am. Bridgetower sight-read the sonata; he had never seen the work before, and there had been no time for any rehearsal.

After the premiere performance, Beethoven and Bridgetower fell out: while the two were drinking, Bridgetower apparently insulted the morals of a woman whom Beethoven cherished. Enraged, Beethoven removed the dedication of the piece, dedicating it instead to Rodolphe Kreutzer , who was considered the finest violinist of the day.

After its successful premiere in 1803, the work was published in 1805 as Beethoven’s Op. 47, with its re-dedication to Rudolphe kreitzer , which gave the composition its nickname. Kreutzer never performed the work, considering it “outrageously unintelligible”. He did not particularly care for any of Beethoven’s music, and they only ever met once, briefly.

He exhibited considerable talent while still a child and gave successful violin concerts in Paris,London,Bath and Bristol in 1789. In 1791, the British Prince Regent , the future King George IV ,took an interest in him and oversaw his musical education.

George Xiaoyuan Fu at the Wigmore Hall with feats of musical trickery and mastery

Stephen Kovacevich Mastery and Mystery at St Mary’s with Tamsin Whaley-Cohen

Their biographies are included in these previous articles .Tamsin plays the ex Laurand Feneves Strad

Although Mr. Fenyves never published any books (he revealed to me that he didn’t have interest in writing or publishing), he did leave behind several recordings documenting his interpretive intelligence, as related to various works of Hungarian composer Béla Bartók, in addition to his concertmaster work with Orchestre de la Suisse romande under Ernest Ansermet (among them, Rimsky Korsavakov’s Scheherezade). At his 80th birthday concert, Mr. Fenyves performed the Beethoven Violin Concerto at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto and that night, was awarded Hungary’s Cross of the Order of Merit.

Marking his 80th birthday, on February 20, 1998, the Globe and Mail dubbed Mr. Fenyves as “one of the greatest violin teachers in the world” . At his memorial concert held in Toronto in 2004, musicians flew in from around the world to honour him and his contribution to Classical music. In 2012, the documentary film, Orchestra of Exiles, featured Mr. Fenyves’ story detailing his participation in Bronislaw Huberman’s orchestra of Jewish musicians, which later became the Israel Philharmonic.

Despite the accolades, Mr. Fenyves, a man of utmost integrity, never allowed ego to pollute his art nor stand in the way of the growth of his many students worldwide. For this, Mr. Fenyves cultivated many loving disciples on multiple continents.