Bartók 14 Bagatelles, Op.6

Liszt Bagatelle without tonality, S.216a

Beethoven 15 Variations and Fugue on an original theme

in E flat (Eroica), Op.35

Interval

Bach Chorale-prelude, Nun freut euch, lieben Christen gmein, BWV.734 arr. Kempff

Bach Chorale-prelude, Nun komm’ der Heiden Heiland, BWV.659 arr. Busoni

Dowland In darkness let me dwell (a recording for voice & lute)

Thomas Adès Darknesse visible

Beethoven Sonata in A flat, Op.110

It was a sign of the esteem that Imogen Cooper has earned over her long career ,in which musical standards have reigned sovereign over the transcendental pianism that has taken centre stage over the past forty years ,to see so many illustrious musicians in the audience on this particularly cold last month of the year.

In the audience was Alfred Brendel who with great difficulty negotiated the freezing temperatures and endless steps to salute one of his greatest protégées.Dame Janet Baker ,Dame Jane Glover ,Gyorgy Pauk and many young musicians from the Imogen Cooper Music Trust ,including the now distinguished pianist Cristian Sandrin,that she has so generously helped to advance in their musical understanding.

It was Imogen who after her much criticised studies in Paris as her father ,Martin Cooper,the great musicologist and critic advocated the great British Musical Institutions for study rather than the almost obligatory period ‘abroad’. He had sent his daughter to study with Yvonne Lefebure ,though,in Paris .On her return after hearing Brendel play she told him that she would commit suicide if he would not become her mentor.

In the very first lesson twenty minutes were spent on perfecting just one chord !

I remember Imogen who had just returned from Paris and delighted Vlado Perlemuter in his Dartington Masterclass in 1967 not only with her superb playing of Ravel ‘Valses’ but also on her perfect French.

In the audience tonight there were also many young pianists including the winners of the Leeds ,Alim Beisembayev and Ariel Lanyi , where Imogen has taken over the reigns from that other great Dame: Fanny Waterman.

At the end of the recital it was Lady Weidenfeld who exclaimed to me what marvels had been heard and she should know having known two of the greatest musicians of our time .She has for long been associated with the Rubinstein Competition of which Janina Fialkowska had been a top prize winner in the very first edition.

Rubinstein himself had supervised a career that she was not expecting.She just wanted to meet her idol before taking up a career in law but had studied in Paris too with the remarkable Yvonne Lefebure and she and Imogen became lifelong friends.

They both have something in common ,that Rubinstein and Brendel had noted: they think more of music than themselves.

A humility and integrity and above all their artistry is placed at the service of the composer.’Je sens ,je joue je trasmets.’

It was this that came across today and left the many musicians present moved to crowd to the green room to thank our adored Dame for her unflinching dedication to values that are fast evaporating .Quantity rather than quality is the name of the game these days.Instant communications where a photo on a mobile device can be seen instantly the other side of the globe and where a recording of a performance can be kept forever.It was Gilels who said that the difference between a recorded performance and a live one was the difference between fresh or canned food.Mitsuko Uchida refused (gracefully) an enthusiastic fan who wanted her to pose for a ‘selfie’ and exclaimed so astutely that it is the memory of a performance or an encounter that is so much more important than having a printed copy of it.

Imogen Cooper Heart to Heart at the Wigmore Hall

The most remarkable parts of the recital for me were those that are not really associated with Imogen.Dame Imogen has long been associated ,as one would expect from the class of Brendel ,with Schubert and Beethoven.So it came as a surprise to hear Bartok with a kaleidoscopic range of sounds and a chameleonic sense of character.There was the precision of Webern with the feeling that every one of the notes had a fundamental part to play in a musical discourse.They were reminiscent of Prokofiev’s early Vision Fugitives or dare I say Beethoven Bagatelles, largely written towards the end of his life, where so little can say so much.Imogen had distilled the very essence from each of these fourteen miniature jewels that kept her audience in rapt silence of wonderment.The Liszt Bagatelle just entered on the trail of the Bartok which was immediately apparent by the sudden jeux perlé brilliance and scintillating sense of dance of what was the originally projected Fourth Mephisto waltz.

Plunged into pitch darkness as we listened with baited breath to Dowland’s ‘In Darkness let me dwell’ in a recording of voice and lute.The curtain was gradually raised to the pungent multicoloured sounds of Thomas Adès’s atmospheric ‘Darknesse visible’.Here again Dame Imogen had a range of colours helped by a masterly use of the pedals that made the music speak just as eloquently as her Beethoven.And it was Beethoven this time that crept in on these magic sounds and they gave a golden glow to the opening of a work that Dame Imogen has made very much her own over the years.There was a warmth to the sound of the whole Sonata that seemed to be sheltered under a dome that contained within its walls a world of intimate beauty and as Dame Imogen so eloquently said in words and even more in music ‘affirms the return to life that gives us hope and strength to go forward’.It was the same sound world that the Eroica variations had inhabited where even the more strenuous variations were incorporated into an architectural sound world and not played as gymnastic exercises. If she missed the ravishing sense of elegance and sheer physical exhilaration that Curzon brought to the variations – that he too played from the score as time and tide wait for no man in long and illustrious careers – It was though the beauty of the sound that was so convincing as Imogen ,like her illustrious predecessors Dame Myra and Dame Moura both from the class of Uncle Tobbs,has like those of the Matthay school an infinite variety of sounds in every note that can make the music speak with such eloquence.The two chorale preludes by Bach -Kempff and Busoni I well remember Kempff playing in this very hall fifty years or more ago……Busoni unfortunately I never heard live but I have heard his recording and quite frankly what we heard tonight was even more enlightened as I am reminded of what Dame Mitsuko said about printed photos!Moved by the audience reaction and overwhelming ovation Dame Imogen gave an even more convincing performance of Bartok with his Durge op 9 n. 1.

There is obviously nothing like a Dame !

Dame Imogen writes:

“The construction of this programme has two strands to it, clearly in each half. The Bartók /Liszt group is a little teaser around tonality; the Liszt Bagatelle sans tonalité is a fantastic piece but difficult to programme as very short and not really belonging anywhere. After choosing the Bartók Bagatelles Op.6 – a masterpiece so rarely heard – it occurred to me that Bartók too was playful with tonalities and keys – the first bagatelle is written with the right hand in C sharp minor and the left hand in C minor (fairly novel for 1908) and in the successive bagatelles, he hardly stays in the keys he initially chooses. It seemed the obvious work into which to insert the Liszt, not least as, surprisingly, there were only around 25 years between the two compositions – and both composers were of course from Hungary. I like the idea of a certain aspect of destabilisation when listening, and my insertion of the Liszt in the body of the Bartók work is randomly placed in the sequence.

I hope that this does justice to the wit and originality of both composers.

It certainly makes the return to full tonality in the Beethoven Eroica Variations all the more startling, with the call to arms of the opening E flat major chord. There is wit aplenty in this work too, as so often in this particular form of Beethovenian composition – a certain wild energy too, and little melancholy.

In the second half of the recital, I have an image of a descent from joyfulness into dark depths followed by

a kind of triumphal resurrection. The first of the Bach chorales is ebullient and optimistic, the second reflective and sombre. Dowland then takes us into real blackness with his extraordinary poem, from which Adès’ glittering rejoinder emerges, with its final two lines a direct quote of Dowland’s music. Somehow the only exit from there has struck me as being Beethoven’s Op.110 Sonata, which comes as balm to the soul as it starts on its own journey, not without profound grief in the two great Ariosi, but terminating in an affirmative return to life that gives us hope and strength to go forward.”

Béla Bartók (1881–1945)

14 Bagatelles, Op.6

i Molto sostenuto

ii Allegro giocoso

iii Andante

iv Grave

v Vivo

vi Lento

vii Allegretto molto capriccioso

viii Andante sostenuto

xi Allegretto grazioso

x Allegro

xi Allegretto molto rubato

xii Rubato

xiii Elle est morte. Lento funebre

viv Valse: Ma mie qui danse. Presto.

Béla Bartók was 27 when he composed his Op.6 Bagatelles in 1908, and reeling from romantic rejection by violinist Stefi Geyer, who’d infatuated him for quite some time. He vents his despair and anger in the last two of the 14 pieces: No.13 is a sinister funeral march named ‘Elle est morte’, while the final bagatelle, ‘Valse (ma mie qui danse)’ is a bitter, grotesque waltz. The rest of the set of pithy miniatures, however, are similarly forward- looking, and daringly experimental, from the pianist’s hands playing in two unrelated keys in No.1 to the bracing folk tunes of Nos.4 and 5, from the bare unisons of No.9 to the driving rhythms of No.10.

Franz Liszt (1811–86)

Bagatelle without tonality, S.261a

At a later stage in his life Liszt experimented with “forbidden” things such as parallel 5ths in the “Csárdás macabre”and atonality in the Bagatelle sans tonality (“Bagatelle without Tonality”). Pieces like the “2nd Mephisto-Waltz” are unconventional because of their numerous repetitions of short motives. Also showing experimental characteristics are the Via crucis of 1878, as well as Unstern!, Nuages Gris and the two works entitled La lugubre gondola of the 1880s.

Bagatelle sans tonalité was written by in 1885. The manuscript bears the title “Fourth Mephisto Waltz”and may have been intended to replace the piece now known as the Fourth Mephisto Waltz when it appeared Liszt would not be able to finish it; the phrase Bagatelle ohne Tonart actually appears as a subtitle on the front page of the manuscript.

While it is not especially dissonant, it is extremely chromatic becoming what Liszt’s contemporary Fétis called “omnitonic”in that it lacks any definite feeling for a tonal center.Like the Fourth Mephisto Waltz, however, it was not published until 1955.

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827)

15 Variations and Fugue on an original theme in E flat (Eroica), Op.35

From supposedly lightweight bagatelles to something far weighter, and more heroic. Beethoven clearly loved the theme he used as the basis for his 1802 Op.35 Variations: it began life entertaining Viennese dancers as one of the 12 Contredanses he composed in 1801 for the Austrian capital’s ballrooms, and he went on to use it in his ballet

score The Creatures of Prometheus, and, most famously,

in the finale of his Eroica Symphony (the piece that gives today’s piano work its nickname). Perhaps it’s the tune’s very simplicity that inspired him, or the way he could explode it and explore its potential across a whole range of moods and settings – something he did in the Symphony, and something he similarly does in tonight’s Variations. Beethoven opens with just the theme’s bassline, offering three variations, before moving on to 15 contrasting settings of the tune

as a whole, ending with a richly decorated slow section, a mind-bending fugue, and a dazzling conclusion. With hand- crossings, athletic runs across the length of the keyboard, and free-flowing cadenzas, it’s a piece that’s clearly designed to show off the skills of its performer.

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750)

Chorale-prelude, Nun freut euch, lieben Christen gmein, BWV.734 arr. Kempff

Chorale-prelude, Nun komm’ der Heiden Heiland, BWV.659 arr. Busoni

After pioneering bagatelles and virtuosic variations, there’s

a slightly more sober, even spiritual mood to the concert’s second half. JS Bach wrote no fewer than 46 chorale preludes for organ, works that take well-known hymn tunes and elaborate them with rippling accompaniments, unusual harmonies and more – often to prepare a congregation to sing the hymn in question itself. A tradition of reworking these organ pieces for piano has continued since the 19th century, bringing Bach’s creations out of the church and

into concert halls and even private homes. Pianist and composer Wilhelm Kempff made his piano version of Bach’s ‘Nun freut euch, lieben Christen gmein’ (Now rejoice, dear Christians) in 1926, reimagining the original organ piece from Bach’s Weimar years between 1708 and 1717 as a brisk and joyful piano creation. Italian composer Ferruccio Busoni – a devoted admirer of Bach – saw transcribing, adapting and freely composing as part of the same musical continuum, and one that Bach himself had also explored. The original Chorale Prelude ‘Nun komm’ der Heiden Heiland’ (Come, saviour of the nations) weaves a web of sometimes anguished lines around its 1524 hymn tune, with words by Martin Luther. Busoni’s piano version maintains the original’s poignant interplay of melody and accompaniment voices in music that’s sometimes dramatic and despairing, other times moving and meditative.

John Dowland (1562/3–1626)

In darkness let me dwell (a recording for voice & lute)

Composer, lutenist and singer John Dowland was a musical superstar in the 16th and 17th centuries, with an output of often deeply troubled, melancholic lute songs that charmed and captivated admirers across a growing English middle class, who’d even take up the instrument to emulate him (Henry VIII, for example, insisted that his three children

– who’d become Edward VI, ‘Bloody’ Mary and Elizabeth I – each learned the lute). Published in 1610, ‘In darkness let me dwell’ is one of Dowland’s most bleakly beautiful creations,

a setting of an anonymous poem (see below), included in

the 1606 Funeral Teares collection by John Coprario, whose writer abandons light, music, or any sense of consolation, preferring the peace of the grave. The song’s grinding dissonances, halting structure and apparently premature, cut-off ending only serve to emphasise its overall despair and resignation.

In darkness let me dwell

In darknesse let mee dwell

the ground shall sorrow be,

The roofe Dispaire to barre

all cheerfull light from mee,

The wals of marble black

that moistened still shall weepe, My musicke, hellish, jarring sounds to banish friendly sleepe.

Thus wedded to my woes, and bedded to my Tombe, O let me living die,

till death doe come.

Thomas Adès (b.1971)

Darknesse visible

Thomas Adès is one of the world’s most celebrated musicians. A composer, pianist, and conductor, Adès’s comfort in thinking through his works both structurally and pragmatically (though his personal virtuosity often begets scores with an unforgiving level of difficulty) yields music that is not only smart but incredibly moving and communicative. While he is definitely a British composer, Adès has spent a great deal of time on both coasts of the United States, both in his ad- opted second hometown of Los Angeles and in Massachusetts, where he serves as the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s artistic partner as well as director of the Tanglewood Music Center’s Festival of Contemporary Music.

Darknesse Visible is Adès’s “explosion” of a lute song by the composer John Dowland, “In Darknesse Let Mee Dwell,” composed in 1610. Adès writes:

No notes have been added; indeed, some have been removed. Patterns latent in the original have been isolated and regrouped, with the aim of illuminating the song from within, as if during the course of a performance.

In darknesse let mee dwell,

the ground shall sorrow be,

The roofe Dispaire to barre

all cheerful light from mee,

The wals of marble blacke

that moistned still shall weepe, My musicke hellish jarring sounds to banish friendly sleepe.

Thus wedded to my woes, and bedded to my Tombe, O let me living die

till death doe come.

Dowland ends the song with a restate- ment of the opening line.

His austerely powerful work is a far more radical transformation than Kempff and Busoni’s piano reimaginings of Bach, though its piercing accents, its wavering tremolos and its ghostly, blurred harmonies provide a compelling contemporary perspective on Dowland’s deep melancholy.The World premiere: October 1992 at the Franz Liszt House, Budapest, Hungary, with the composer as piano soloist

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827)

Piano Sonata in A flat, Op.110

Moderato cantabile molto espressivo

Allegro molto

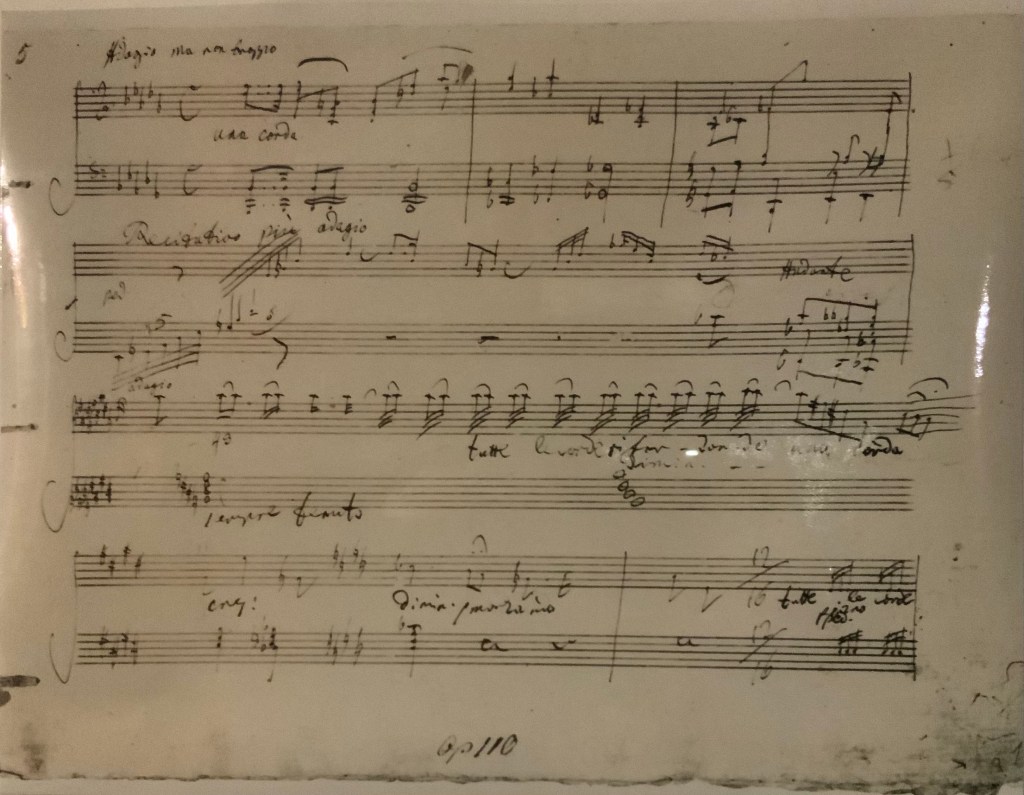

Adagio ma non troppo – Fuga allegro ma non troppo

From darkness and death to spiritual transcendence. Beethoven the young pioneer, out to demonstrate his compositional and pianist prowess in the earlier Eroica Variations, had become a very different composer two decades later, when he came to write his final trilogy of piano sonatas: more contemplative, philosophical, even otherworldly. Op.110 is the middle sonata in the trilogy, composed in 1821 and published the following year, and it packs a huge amount of drama, insight and innovation into its relatively brief 20-minute span. A prayer-like theme (marked ‘amiable’) opens its tender first movement, whose ethereal beauty is quickly dispelled

by the boisterous, earthy second movement, based on two German folksongs. To end, Beethoven effectively combines two separate movements: first a tragic, song-like lament (you might even hear certain resonances from Dowland), and second a vigorous, life-affirming fugue that builds to a shattering climax. The lamenting song returns, exhausted, only for the music to gather confidence (Beethoven indicates ‘little by little gaining new life’) as it heads towards its joyful, transcendent climax.

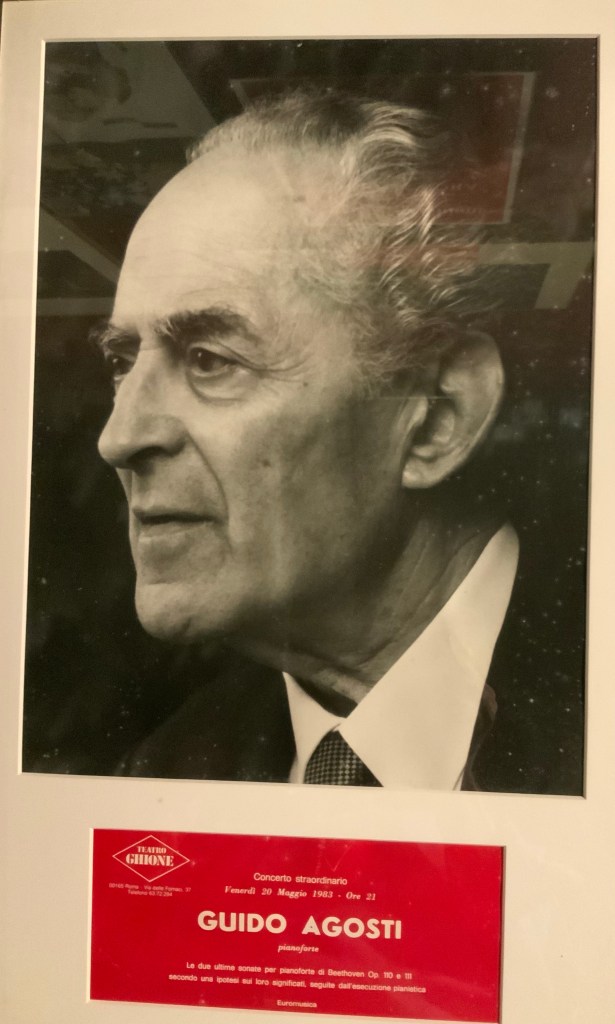

The legendary Guido Agosti held summer masterclasses in Siena for over thirty years.All the major pianists and musicians of the time would flock to learn from a master,a student of Busoni,where sounds heard in that studio have never been forgotten.He was persuaded by us in 1983 to give a public performance of the last two Beethoven Sonatas.The recording of op 110 from this concert is a testament,and one of the very few CD’s ever made,of this great musician .

https://christopheraxworthymusiccommentary.com/2023/04/14/nicolo-giuliano-tuccia-a-true-musician-with-something-important-to-say-from-the-city-of-the-legendary-guido-agosti/

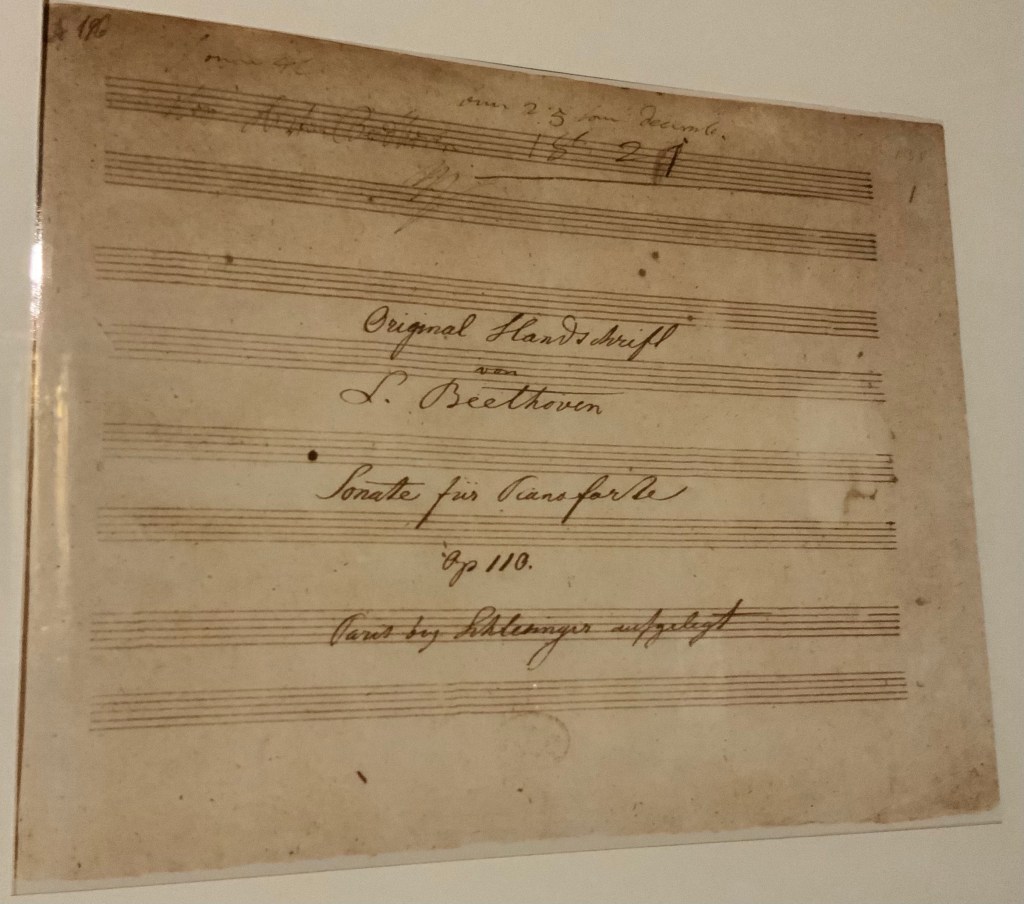

In the summer of 1819, Adolf Martin Schlesinger from the Schlesinger firm of music publishers based in Berlin sent his son Maurice to meet Beethoven to form business relations with the composer.The two met in Modling,where Maurice left a favourable impression on the composer.After some negotiation by letter, the elder Schlesinger offered to purchase three piano sonatas for 90 ducats in April 1820, though Beethoven had originally asked for 120 ducats. In May 1820, Beethoven agreed, and he undertook to deliver the sonatas within three months. These three sonatas are the ones now known as Op. 109,110, and 111 the last of Beethoven’s piano sonatas.

The composer was prevented from completing the promised sonatas on schedule by several factors, including his work on the Missa solemnis (Op. 123),rheumatic attacks in the winter of 1820, and a bout of jaundice in the summer of 1821.Op. 110 “did not begin to take shape” until the latter half of 1821.Although Op. 109 was published by Schlesinger in November 1821, correspondence shows that Op. 110 was still not ready by the middle of December 1821. The sonata’s completed autograph score bears the date 25 December 1821, but Beethoven continued to revise the last movement and did not finish until early 1822.The copyist’s score was presumably delivered to Schlesinger around this time, since Beethoven received a payment of 30 ducats for the sonata in January

Some of the young musicians who have been so generously helped by The Imogen Cooper Music Trust :

Cristian Sandrin – The Imogen Cooper Music Trust

Nothing like a Dame!Aidan Mikdad ignites the Imogen Cooper Music Trust – part 1 and 2

Ignas Maknickas fluidity and romance for the Imogen Cooper Music Trust

Ariel Lanyi – Imogen Cooper Music Trust The trials and tribulations of a great artist