Live at the BBC Proms: celebrated British pianist Benjamin Grosvenor performs Debussy’s Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune and Ravel’s Le tombeau de Couperin.

Debussy arr. Borwick: Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune

Liszt: Réminiscences de Norma

Ravel: Le tombeau de Couperin; La valse

Benjamin Grosvenor, piano

A regular at the Proms since his debut here over a decade ago, former BBC Young Musician of the Year Finalist Benjamin Grosvenor brings a selection of transcriptions and arrangements of works better known in other guises. The sensuality of Debussy’s Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune melts into Ravel’s tender Le tombeau de Couperin suite and his heady, war-scarred La valse, while a passing visit to the Italian opera comes courtesy of Liszt’s virtuosic reimagining of Bellini’s Norma, a bel canto tale of warring Druids and Romans, set in ancient Gaul.

It was at the end of the morning recital in the vast space that is the Royal Albert Hall when Benjamin Grosvenor having astonished,amazed and seduced us with diabolical transcriptions as Liszt and Thalberg must have done in their day.He gave a whispered account of Saint Saëns ‘ The Swan’ in Godowsky’s magic transcription.Streams of golden sounds,insinuating counterpoints and a ravishing sense of balance drew this vast crowd in to him to eavesdrop on a performance of delicacy and poetic artistry.A sense of rubato and timing that held us all in his hand as he stretched and shaped the sounds with the same artistry that Godowsky himself must have shared with his public in the ‘Golden Era’ of piano playing.An era where transcendental mastery of the keyboard meant that with the same skill as an illusionist Rosenthal,Levitski ,Lhevine or Hoffman could persuade us that the piano could sing with the same subtle inflections as the greatest of Bel canto singers.They could also persuade us that the piano could roar and shout with the same sumptuous sounds as the Philadelphia Orchestra that Rachmaninov so admired.

It was the same piece that Cherkassky played at his own funeral in 1995 in Hanover Square.A work he had played many times in a long career since his child prodigy days with Hoffman .Horowitz often used to say to Shura that we are the only two left from the Golden Age of piano playing.Shura gave ten recitals in my season of Euromusic in Rome and knowing that I video recorded all the performances Piero Rattalino asked me if he could have the recording of his Albeniz/Godowsky Tango.Not Morton Gould’s Boogie Woogie study or the Eugene Onegin Paraphrase.It was the subtle way of caressing the keys and savouring the intoxicating sounds that interested a Professor who knew more about pianists and piano playing than anyone alive.There was an article in ‘Le Monde de la Musique’ about Cherkassky the title was ‘Je sens,je joue,je trasmets’ and it is exactly this that sums up his artistry and those like Horowitz and Rubinstein where the audience is an essential part of this recreation.Rubinstein famously said that there must always be risk and the unexpected in playing in public and that one should not have a printed copy ready to trot out in public.It is an act of love,said Rubinstein the greatest lover of all time!

It is this act of love that we were witness to today with Benjamin Grosvenor in an astonishing display not only of pyrotechnics and breathtaking agility but of his palette of kaleidoscopic sounds that he could project out to his audience with devastating effect but that he could also draw in to him with the intimacy of a ritual of almost indecent seduction of the senses.

It was from the very first notes of Debussy’s ‘Après midi’ that we were made away of the luminosity of the flute solo that we know so well.Here was a transcription by a student of Clara Schumann that I have heard from lesser hands in rather black and white performances that made one wonder whether it was a necessary addition to the already saturated piano repertoire.Researching Leonard Borwick he was described as a poet of the keyboard,a painter of pianistic colours,he communed with beauty and saw visions.It was exactly this that could describe the magic that Benjamin Grosvenor conjured out of the piano today.A magic sweep of sounds-not individual notes – a sumptuous bass that gave an anchor to rays of sound that could float on a magic carpet of gold and silver.There were very precise clear sounds too as the woodwind added their individual sound world to this timeless beautiful landscape of radiance and slumbering beauty.

The mighty call to attention of Norma broke the spell with its rhythmic precision where even the rests became so ominous.A sumptuous bass accompaniment of transcendental octaves that became a shimmering accompaniment to the the glorious bel canto melodies of Bellini.Anton Rubinstein said the pedal is the soul of the piano and it was Benjamin’s wondrous use of the pedal that could convince us that there were many more hands and feet involved as Thalberg had done in the fashionable salons of the day .A way of floating the melodic line in the tenor register with swirls of arpeggios and scintillating scales all around.Like Paganini on the violin there was something superhuman and diabolic to the way the themes from the popular operas of the day could be transformed into an orchestra of breathtaking dimension by artists that were feted like the pop stars of their day.Benjamin Grosvenor created the same fervour and breathtaking excitement today with the sumptuous sounds of a truly ‘Grand ‘piano.There was never an ungrateful or hard sound in a recital that drew the pianist to the limits of technical funabulism.What control of sound that at the build up of tension could suddenly reduce the sound without changing the red hot drive.It meant that at the absolute climax he could still have the sumptuous full sound as the two main melodies combined in a moment of delirious passion ending with a virtuosity of breathtaking daring.I am reminded of the same mastery of Gilels who had us sitting on the edge of our seats in the Festival hall in London ,as he brought a relentless drive to Liszt’s Spanish Rhapsody with a grandeur of sumptuous sounds in a performance that like today will go down in history.

There was absolute clarity to each of the six pieces that make up Ravel’s ‘Le Tombeau.’ A golden stream of sounds in the ‘Prelude’with the occasional clicking of heels as it arrived at the final glowing trill ending.Deep melancholy of the ‘Fugue’ played with ravishing colour and remarkable architectural shape.There was a beguiling lilt to the ‘Forlane’ and a rhythmic energy to the contrasting ‘Rigaudon’.There was a beautiful flowing central episode of infectious dance on which Ravel – like Schubert – floated a magical outpouring of melody before the return of the Rigaudon.Subtle shading and beauty of the Minuet with its plain chant central episode was played with disarming simplicity.The Minuet just floated on top of this chant disappearing to a whispered trill on high.There was clockwork precision of the ‘Toccata.’Not just dry precision but something that was like a live wire of driving rhythmic impulse where again – like Schubert – Ravel has an outpouring of mellifluous beauty and radiance like a cloud lifting to show a ray of light as the toccata picks up momentum leading to the tumultuous final explosion of glory and excitement.

La Valse was truly overwhelming starting with the ominous opening rumble deep in the bass but with such clarity of line as streams of sounds of steamy decadence took over.A sophisticated elegance of a past era always with the insistent dance rhythm so clearly defined no matter how seedy things became.Breathtaking glissandi and tricks of the trade as the piece reaches the boiling cauldron with unbelievable technical demands of the player.Ravel obviously trying to outdo himself and Balakirev with the transcendental virtuosity that Liszt had led the way inspired by the Devil with a violin himself!

I remember Fou Ts’ong telling me it was easier to be more intimate in a big space than in a small one.Benjamin Grosvenor just proved how true that was as he barely whispered the sounds as we strained to hear.But like all great artists he has a diaphragm that can send the most intimate of messages to the front row of the hall but can project with the same intensity to the very last row in ‘Paradiso’ the ‘Gods’.A secret of only the greatest musicians that can feel the vibrations in their body and know that they will arrive safely to their destiny.I remembered too in this hall Raymond Lewenthal who appeared on stage with a lamp standard by the piano to give the appearance of an intimate salon as he played the ‘Moonlight’ and Chopin’s first Ballade,hoping to create the atmosphere of a Busoni,much to the perplexity of his agent Wilfred van Wyke Unfortunately it was not until he set the piano on fire with the Hexameron where fireworks started to fly with the same sensational performances of Liszt that had London at his feet with queues all around the Wigmore Hall.

Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune (L. 86), was composed in 1894 and first performed in Paris on 22 December 1894 inspired by the poem by Stephane Mallarmé .It is one of Debussy’s most famous works and is considered a turning point in the history of Western Music .Pierre Boulez considered the score to be the beginning of modern music observing that “the flute of the faun brought new breath to the art of music.”

Debussy wrote :”The music of this prelude is a very free illustration of Mallarmé’s beautiful poem. By no means does it claim to be a synthesis of it. Rather there is a succession of scenes through which pass the desires and dreams of the faun in the heat of the afternoon. Then, tired of pursuing the timorous flight of nymphs and naiads , he succumbs to intoxicating sleep, in which he can finally realize his dreams of possession in universal Nature.”

Transcribed for piano solo by Leonard Borwick

Leonard Borwick was an English concert pianist especially associated with the music of Robert Schumann and Johannes Brahms.His London debut was on 8 May 1890, at a Royal Philharmonic Society concert concert, in Schumann’s Piano Concerto . He performed it again in London on 12 June, and on 17 June in a concert for Hans Richter .He also played the Brahms D minor concerto which George Bernard Shaw called ‘a hash of bits and scraps with plenty of thickening in the pianoforte part, which Mr Leonard Borwick played with the enthusiasm of youth in a style technically admirable’. Shaw recommended that he should embark on recitals.Borwick played Brahms’s D minor concerto under Hans Richter in Vienna in 1891. Brahms himself was at this concert, and wrote to Clara Schumann that her pupil’s playing had contained all the fire and passion and technical ability the composer had hoped for in his most sanguine moments. Clara Schumann wrote to Professor Bernuth in Hamburg to recommend Borwick as ‘probably her finest pupil: I never heard the A minor concerto of Schumann nor the D minor of Brahms played better.’In 1921 he gave two recitals in the Aeolian Hall in March and April, which included his transcription of Debussy’s Prelude a l’apres-midi d’un faune (originally premiered for him by Mark Hambourg ).He is remembered as a poet of the keyboard, a great painter of pianistic colours, who possessed a very broad range of expression from the most delicate touch to a fire and resource of tonal depth greater than that usually associated with the Clara Schumann school. Plunket Greene remembered how he communed with beauty and saw visions, his reverence, quiet simplicity, and his avoidance of personal publicity. He made no gramophone records. The Royal College of Music awards a Leonard Borwick Pianoforte Prize to outstanding students.

Liszt undertook the challenge of diluting Bellini’s opera Norma into a 15 minute solo piano work in 1841. The work easily equals the dramatic impact of the original opera through Liszt’s dynamic and highly virtuosic writing. No less than seven arias dominate Liszt’s transcription of Norma which are threaded together to create a nearly continuous stream of music.The title role of Norma is often said to be one of the hardest roles for a soprano to sing, and this adds to the drama and intensity of the music. A brief summary of the opera has been described by Greg Anderson:

“Norma, a priestess facing battle against the Romans, secretly falls in love with a Roman commander, and together they have two illegitimate children. When he falls for another woman, she reveals the children to her people and accepts the penalty of death. The closing scenes and much of the concert fantasy reveal Norma begging her father to take care of the children and her lover admitting he was wrong.”

The complex music represents the tragedy woven into this story, which is perhaps why Liszt made the effort to transfer the challenges of this score into a piano fantasy. With cascading arpeggios, massive interval changes and dynamic changes at every turn, Réminiscenes is a true test of technical ability. The score is saturated with huge chordal movement, fast-paced cadenza sequences and a raffle of different tempo markings. Pianist Leslie Howard described the work as “a triumph of understanding not just of Bellini’s masterpiece, but of practically all the sound possibilities of the piano in Romantic literature.”

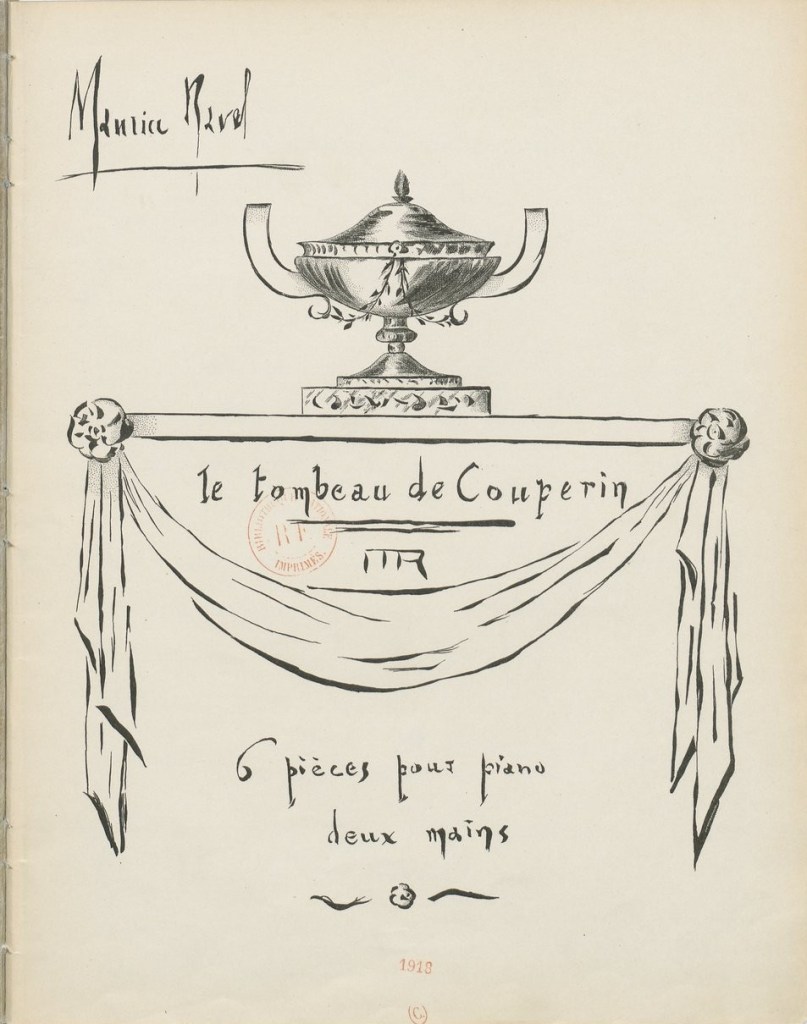

Le Tombeau de Couperin (The Grave of Couperin) is a suite for solo piano composed between 1914 and 1917. The piece is in six movements, based on those of a traditional Baroque suite. Each movement is dedicated to the memory of a friend of the composer (or in one case, two brothers) who had died fighting in World War 1.Written after the death of Ravel’s mother in 1917 and of friends in the First World War, Le Tombeau de Couperin is a light-hearted, and sometimes reflective work rather than a sombre one which Ravel explained in response to criticism saying: “The dead are sad enough, in their eternal silence.”Ravel stated that his intention was to pay homage more generally to the sensibilities of the Baroque French keyboard suite,not necessarily to imitate or pay tribute to Couperin himself in particular. This is reflected in the piece’s structure, which imitates a Baroque dance suite.

IPrelude in memory of Lieutenant Jacques Charlot IIFugue in memory of Jean Cruppi IIIForlane in memory of Lieutenant Gabriel Deluc IVRigaudon in memory of Pierre and Pascal Gaudin VMinuet in memory of Jean Dreyfus VIIToccata in memory of Captain Joseph de Marliave

The idea of writing a score on a great waltz occurred to Ravel as early as 1906 and in February he wrote to his friend Jean Marnold: “What I am undertaking now is not refined: a great waltz, a sort of homage to memory of the great Strauss, not Richard, the other, Johann. You know my intense sympathy for these adorable rhythms and how much I esteem the joy of living expressed by dance” After a short time the project began to take shape in the musician’s mind, so he thought of writing a sort of apotheosis of the waltz, a symphonic poem entitled Wien and dedicating it to Misia Sert , his friend and supporter Diaghilev listened to the composition in a version for two pianos performed by the author and Marcelle Meyer in the presence of Stravinsky and the choreographer Serge Lifar.The impresario, after the audition, declared that it was certainly a masterpiece, but it could not possibly be used for a ballet; according to Lifar, Ravel’s score for Diaghilev paralyzed any possibility of creating a choreography . Ravel, hurt by the comment, broke off all contact with the impresario.La valse soon became a popular concert venue work, and when the two men met again in 1925, Ravel refused to shake Diaghilev’s hand. The impresario challenged Ravel to a duel,but his friends persuaded Diaghilev to recant. The two men never met again. The manuscript of the piano version, which is actually the first version, albeit intended as a draft for the symphonic version, is kept in the Pierpoint-Morgan Library in New York.The temptation to “re-transcribe” for solo piano from the version for orchestra is however strong for all performers, and various pianists, starting with Thiollier , have introduced some small additions taken from the score into Ravei’s text. Glenn Gould thought that Ravel’s piano version was mediocre overall and prepared a transcription of his own ,very virtuosic and influenced by the style of Liszt. Gould’s transcript has not been published to date. But the problem he raised remains open:

Benjamin Grosvenor at the Wigmore Hall-a voyage of discovery with a seamless stream of golden sounds.