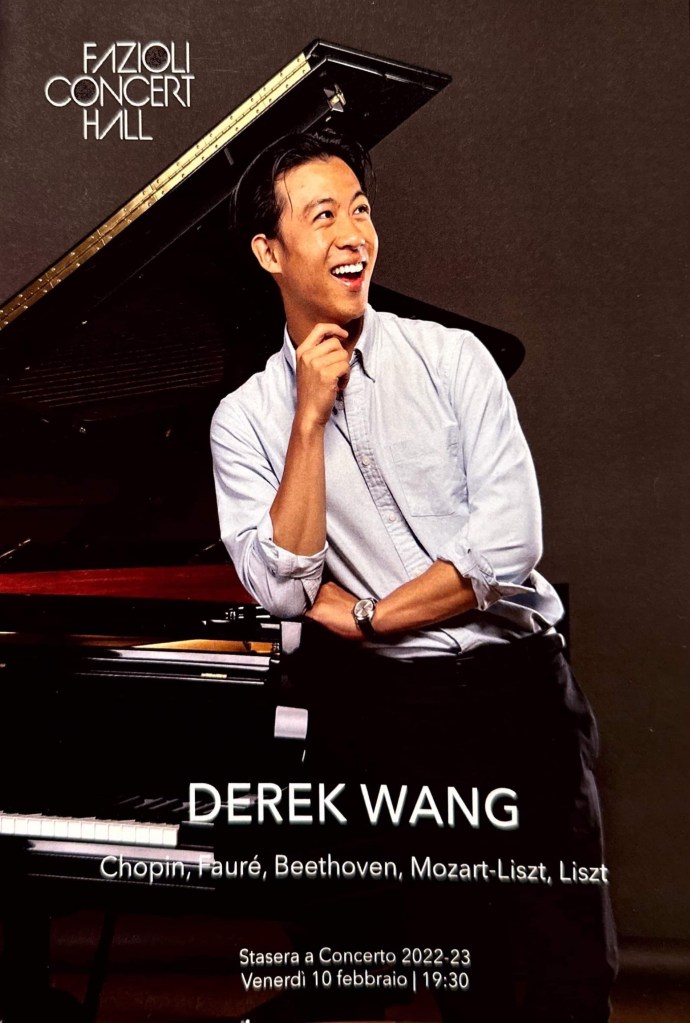

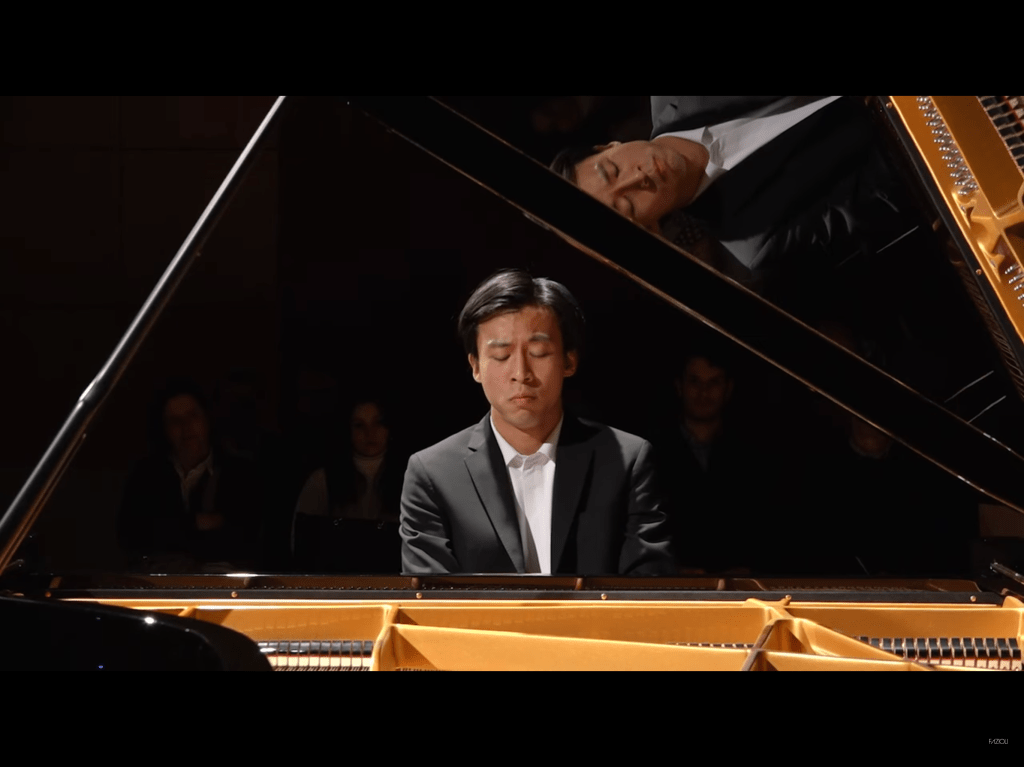

With the “pure poetry” of his playing (Seen and Heard International), pianist Derek Wang is drawing increasing acclaim from audiences and critics alike in wide-ranging appearances as soloist, collaborator, and communicator. A musically eloquent proponent of the original works and virtuosic transcriptions of Franz Liszt, Derek was awarded second prize at the 12th International Liszt Competition (Liszt Utrecht) in the Netherlands in 2022, which followed on the heels of first prize at the inaugural New York Liszt Competition in 2021. Deeply experienced in contemporary music, Derek held a three-summer-long fellowship position as pianist of the Aspen Contemporary Ensemble at the Aspen Music Festival under conductors Donald Crockett and Timothy Weiss, performing a total of over fifty works of the 20th and 21st centuries. Derek holds Bachelor and Master of Music degrees from The Juilliard School, where he received a Kovner Fellowship and the Joseph W. Polisi Prize for exemplifying the school’s values of the artist as citizen. He continues studies at the Yale School of Music as an Artist Diploma candidate. His principal teachers have included Stephen Hough, Yoheved Kaplinsky, Matti Raekallio, and Boris Slutsky. For more information and the latest concert schedule, please visit www.derek-wang.com.

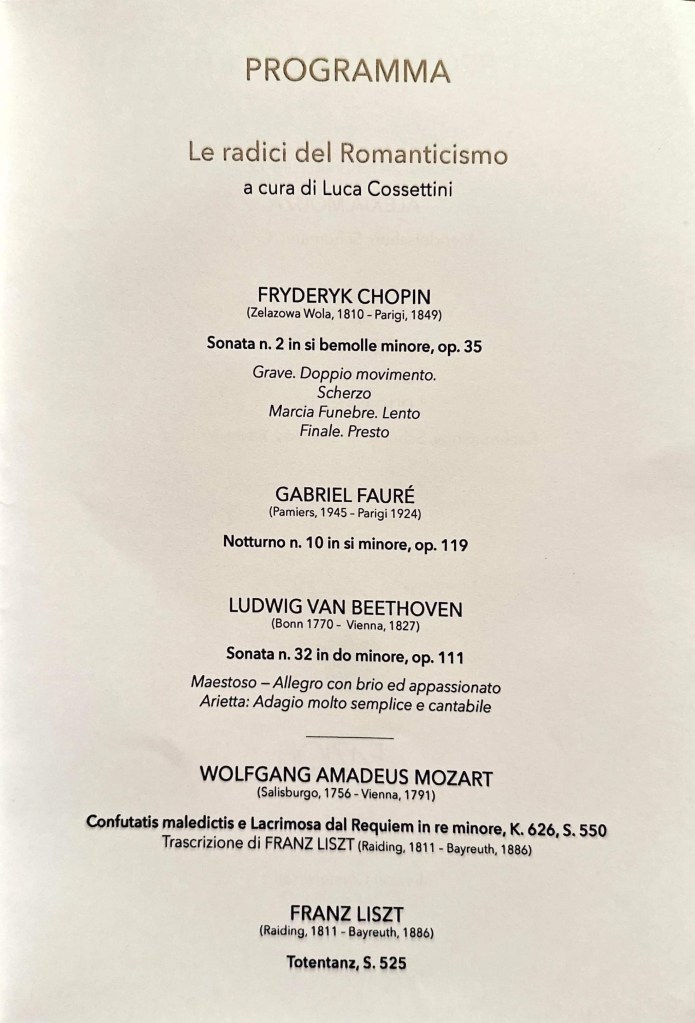

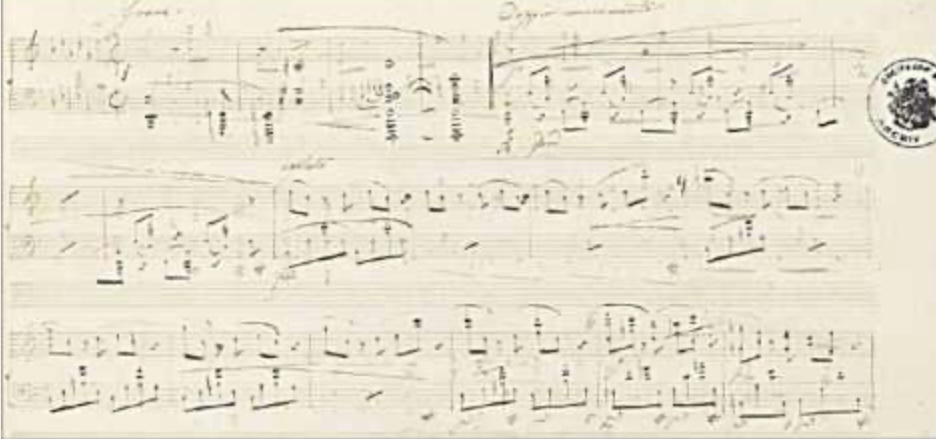

Chopin completed the Piano Sonata n.2 in B flat minor op 35 while living in George Sand’s manor in Nohant some 250 km (160 mi) south of Paris ,a year before it was published in 1840. The first of the composer’s three mature sonatas (the others being the Piano Sonata n.3 in B minor op 58 and the Sonata for Piano and Cello op 65).In a letter on 8 August 1839, addressed to Fontana, Chopin wrote:I am writing here a Sonata in B flat minor which will contain my March which you already know. There is an Allegro, then a Scherzo in E flat minor, the March and a short Finale about three pages of my manuscript-paper. The left hand and the right hand gossip in unison after the March. … When the sonata was published in 1840 in the usual three cities of Paris,Leipzig and London,Paris ,the London and Paris editions indicated the repeat of the exposition as starting at the very beginning of the movement (at the Grave section). However, the Leipzig edition designed the repeat as beginning at the Doppio movimento section. Although the critical edition published by Breitkopf &Hartel (that was edited, among others, by Franz Liszt, Carl Reinecke , and Johannes Brahms)indicate the repeat similarly to the London and Paris first editions, almost all 20th-century editions are similar to the Leipzig edition in this regard. Charles Rosen argues that the repeat of the exposition in the manner perpetrated by the Leipzig edition is a serious error, saying it is “musically impossible” as it interrupts the D♭ major cadence (which ends the exposition) with the B♭ minor accompanimental figure.However, Leikin advocates for excluding the Grave from the repeat of the exposition, citing in part that Karol Mikuli’s 1880 complete edition of Chopin contained a repeat sign after the Grave in the first movement of the Piano Sonata No. 2. Mikuli was a student of Chopin from 1844 to 1848 and also observed lessons Chopin gave to other students – including those where this sonata was taught – and took extensive notes.

Derek decided to eliminate the repeat completely as do so many other great performers like Rachmaninov,Rubinstein,Horowitz,Kissin and Ohlsson.

It was a performance of real weight and with an aristocratic sense of shape and forward propulsion.A restrained and noble ‘Grave’ introduction was followed by the fluidity of the ‘doppio movimento’.If the sostenuto was more symphonic than bel canto it was because of Derek’s great sense of the structure being built up by the harmonies from bass.It was infact in the development where the ‘Grave’ is reworked in the bass that was structurally so beautifully realised.

The coda was played with great excitement and the inevitable drive to the final three chords reminded me of the animal excitement that Rubinstein would suddenly unleash with his aristocratic nobility unexpectedly mixed with animal fervour.

The scherzo had a great sense of line and the long held B flats shone like stars within this impetuously forward moving framework.

It was the ‘più lento’,though,that revealed at last the true ‘bel canto’ and sumptuous use of pedals ,that Derek had been rather over careful with,in his effort not to cloud any detail.

Beautifully shaped with the deep cello melodic line allowed to weave its way so naturally and inquisitively.

If the Funeral March was a little fast for ‘Lento’ it was again like Beethoven’s ‘Arietta’ because Derek was keen to show us the overall architectural shape and never to wallow or sentimentalise such nobly poignant outpourings.

The Trio was beautifully poised and again the sense of ‘bel canto’ was allowed full reign with sumptuous pedal on which the melodic line floated so miraculously.

It was the ‘other’ Rubinstein who stated that the pedal was ‘the soul of the piano’ and nowhere could it have been clearer than in this Trio and the ‘Più lento’ of the Scherzo.The return of the Funeral March was overwhelming with the almost manic insistence of the relentless bass and it was here that I understood Derek’s very intelligent reading of this notoriously popular movement!

The extraordinary wailing Finale was played with astonishing clarity but it missed the washes or waves of sound and the deep throbbing of a melodic line that can be found hidden in its midst by some other pianists.

Chopin himself had not actually indicated any melodic line in the score but I feel it needs some sort of shape or backbone or maybe even more pedal if it is truly to depict the wailing of wind puffing and blowing over such a desolate scene.

As Schumann said about this revolutionary last movement :’What appears in the last movement under the name of Finale is more of an irony than any kind of music.

And yet, it must be confessed, even here […] a strange horrible spirit blows […], so we listen as if fascinated and without protesting to the end – but also without praising, since this is not music”.

Written in 1921, three years before Fauré s death, the tragic despair of the Thirteenth Nocturne shares its depth of feeling with few other works in the piano repertoire. Certainly nothing like this was written by Debussy or Ravel, and only in the last pages of Beethoven, Schubert, Mozart or Bach can parallels be found to its austere heartbreak. The work can be regarded as autobiographical. For the last few years of his life the composer suffered from a distressing hearing defect which caused him to hear distortion in the higher frequencies of the sound spectrum. Knowing this, the chains of suspensions which open this last Nocturne take on an added significance. The piece as a whole is filled with a feeling of regret and farewell,with a vehement and angry middle section rising to a climax of the greatest fury where the unmistakable note of despair which this reveals is all the more affecting. It ends on a note of utter resignation, the music of a man on the threshold of death.The essence of Fauré is in this Nocturne ,and not until one has entered its tragic world can one truly be said to understand him.

Derek offered a deeply felt performance of this extraordinary late work.I remember Perlemuter allowing me to tell the public in Rome,in one of his many recitals for our Euromusica Series,that he had lived as a student in the same house as Fauré who would send his music down to be tried on the piano with the ink still wet.

Derek gave a magnificent intensely personal performance with a kaleidoscope of sounds – ‘sentiment but no sentimentality’ Fauré would implore.

It was exactly this that gave such poignant nobility to this masterly work.He seemed to have freed himself of his intellectual restraints as the ravishing sounds and use of the pedals were all suddenly allowed free reign for the glory of this extraordinary work.A masterly performance with such a clear sense of line and shape allied to an intensity and beauty of sound.

Beethoven conceived of the plan for his final three piano sonatas (Op 109,110 and 111) during the summer of 1820, while he worked on his Missa solemnis. Although the work was only seriously outlined by 1819, the famous first theme of the allegro ed appassionato was found in a draft book dating from 1801 to 1802, contemporary to his Second Symphony.Moreover, the study of these draft books implies that Beethoven initially had plans for a sonata in three movements, quite different from that which we know: it is only thereafter that the initial theme of the first movement became that of the String Quartet n.13 and that what should have been used as the theme with the adagio—a slow melody in A flat – was abandoned. Only the motif planned for the third movement, the famous theme mentioned above, was preserved to become that of the first movement.The Arietta, too, offers a considerable amount of research on its themes; the drafts found for this movement seem to indicate that as the second movement took form, Beethoven gave up the idea of a third movement, the sonata finally appearing to him as ideal.

Some masterly playing with scrupulous attention to Beethoven miraculously precise indications in a score that he could only hear in his head. From the very opening imperious chords with the three great outbursts,each one more intense than the last and each one a risk.This important element of struggle pervades the whole movement before the release into a visionary world of what awaits beyond.Gradually dissolving into the first great gasp of disbelief with the arch of the left hand phrase shaped with Beethoven’s impatience with no half measures but simply ‘sfp’ markings.Its plaintive reply with the beautiful legato of the right hand answer could,though.have been given more weight by playing into the keys – Perlemuter a student also of Schnabel was such a master of this ‘weight’ or ‘organistica’ legato.Derek lacked the inner intensity of something that was about to explode.The full stop on ‘forte’and then the opening theme ‘fortissimo’,often overlooked by many,was magnificently played as the forward drive of the ‘Allegro con brio ed appassionato’ was being felt with the sinister undercurrent that Beethoven prescribes.

A movement that Perlemuter described as like water boiling over at 100 degrees was played with great control and technical mastery but something of the burning intensity and relentless forward drive was impeded by an anxiety to show detail at the expense of the inner meaning of this demonic movement.The staccatos I felt could have been given more weight and the care over the slurs that Beethoven obviously placed to stop virtuosi running amock did not allow the build up of intensity that is so much part of this extraordinary prelude to Beethoven’s vision of what awaits.

The clarity and forward drive of the coda was beautifully played and prepared us for the magical vision in the major.This was,after all,to be Beethoven’s last poignant statement over a lifetime span in thirty two instalments!

Derek had obviously seen the ‘Adagio’ as Beethoven describes with ‘simplicity’ but his string quartet texture although admirable and of fine musicianship did miss the celestial ‘cantabile ‘that Beethoven also asks.The magic atmosphere was not totally created because of this sense of balance and also the fast tempo ,which was maintained throughout,but did not allow us to savour the real perfume of this sublime mellifluous outpouring.The mighty third variation was played with great mastery and his added use of the pedal smoothed over some of Beethoven’s jagged edges to great effect.Dissolving into a cloud of sound on which Beethoven floats fragments of insinuating melody similar to the technique that Sibelius was to use a century later.I found this a little too clean and clear and rather lacking in mystery and suggestion rather than Derek’s more direct statement.It led to the final pages that were beautifully played and the triumphant outpouring of melody was played with ravishing beauty and intensity and where suddenly the vibrations on high mingled with the theme were extraordinarily beautiful.The final three layers of sound led so poetically to the final sighing phrases and the resting place of Beethoven’s vision of paradise with a barely whispered C major chord.

Totentanz (Dance of the Dead): Paraphrase on the ‘Dies irae’, S126 for pianoforte and orchestra is notable for being based on the Gregorian hymn Dies irae as well as for its many stylistic innovations. The piece was completed and published in 1849, and later revised twice (1853-9 and early 1880s. All these versions were also prepared for two pianos). In the late 1860s, Liszt published a version for pianoforte solo, S525. Some of the titles of Liszt’s pieces, such as Totentanz, Funérailles, La lugubre gondola and Pensée des morts show the composer’s obsession with mortality, as well as his profound Christian faith, these things being apparent from Liszt as a teenager right up until his last days – more than 50 years later.

In the last movement of the Symphonie fantastique by Berlioz the medieval (Gregorian) Dies Irae is quoted in a shockingly modernistic manner. In 1830 Liszt attended the first performance of the symphony and was struck by its powerful originality. Liszt’s Totentanz presents a series of variations on the Dies irae – a theme that his will have known since 1830 at the latest from Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique. As an early biographer noted, “Every variation discloses some new character―the earnest man, the flighty youth, the scornful doubter, the prayerful monk, the daring soldier, the tender maiden, the playful child.” A second theme, beginning at variation 6 – taken from the Prose des morts in the Catholic breviary – is itself varied before the first theme returns at the end of the work.

Some masterly playing of amazing pyrotechnics but also what clarity and musicianship he could add to this mind boggling maze of notes.He made the piano roar like a lion and sing like an angel and his intellectual understanding and control gave strength to a work that in lesser hands can appear as a series of circus tricks.

Arrau used to bring the same nobility and seriousness to this work that I heard him play with orchestra in the 70’s.

Derek could have been much freer with the pedal but his enviable technical control and innate musicianship allowed for admirable clarity.I think now he could let the brass and percussion have a fair share in his wonderful orchestra adding two virtuosistic feet to his two wonderful hands!

Mozart’s last unfinished masterpiece, the Requiem, exercised the minds of many nineteenth-century composers, and Liszt confines himself to very clean accounts of the last two portions of the Sequenz: the powerful Confutatis, and the Lacrimosa, of which the textual evidence is that Mozart sketched only the first eight bars and Süssmayr completed it after Mozart’s death. (However, if Süssmayr did write the rest of it makes the question of what he, Mozart and others actually sang around Mozart’s death-bed when, as the biographers tell us, the Lacrimosa was sung.)

A truly overwhelming performance of intensity,fluidity and beauty.Suddenly the piano had become a full orchestra with an extraordinary range of sounds.A sense of balance with a richness of sonority but never harshness.After the tumultuous opening the heavens opened to reveal the very heart of this extraordinary work played with poignant nobility.Liszt’s transcription is a marvel of recreation revealing not only the genius of Mozart but also that of Liszt.

ROME CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL- Superb music making returns to Teatro Argentina